Nations of Canada

The (First) Conquest of Quebec

In the 24th instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ Greg Koabel describes how British adventurers briefly seized Quebec and Acadia following the Anglo-French War of 1627–29.

What follows is the twenty-fourth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialised Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

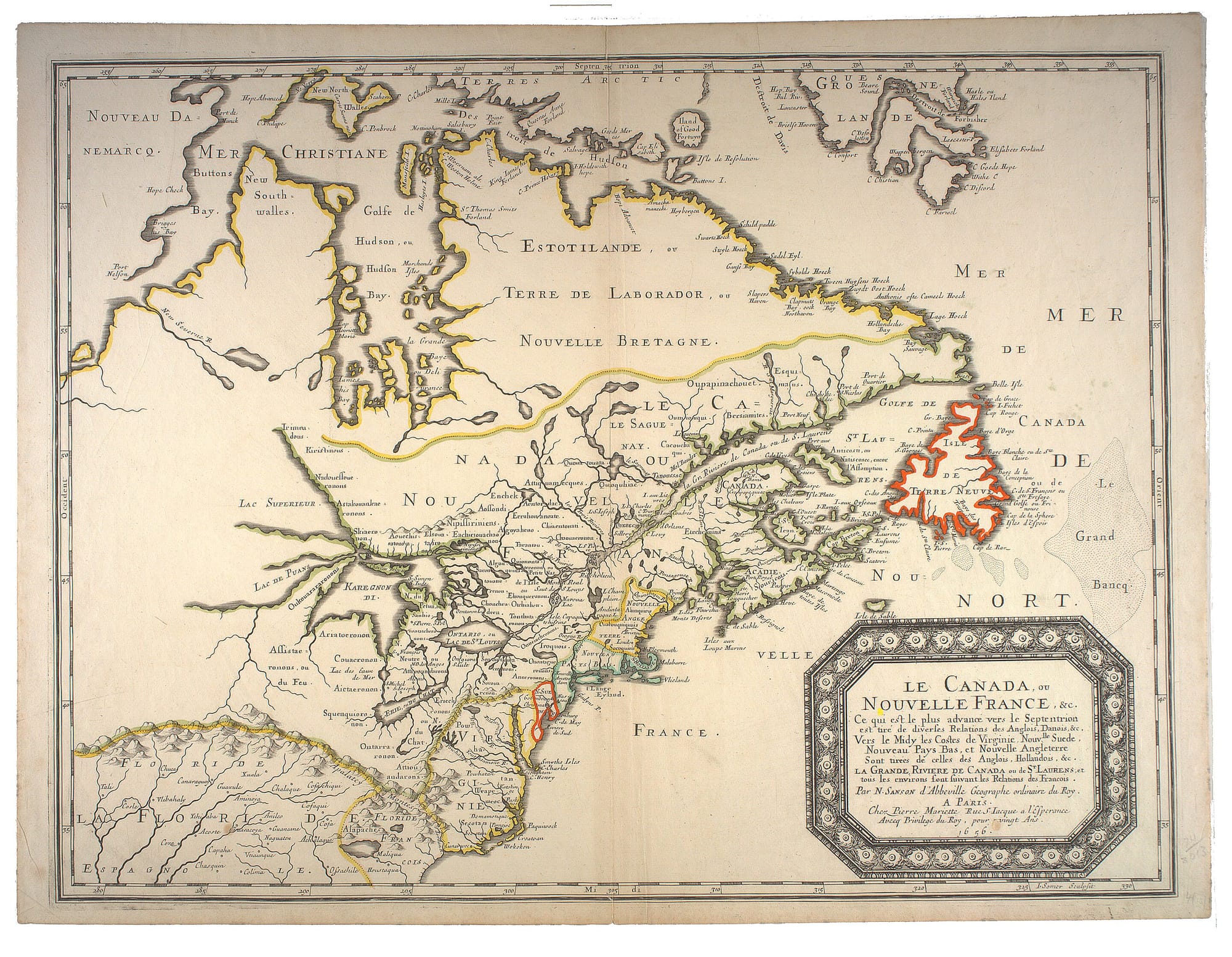

In the summer of 1627, France and England were at war, and the two European empires braced to do battle all over the world. With one important exception: Cardinal Richelieu, who effectively dictated France’s Canadian policy in the name of King Louis XIII, continued colonial operations in Quebec as if the war hadn’t yet begun.

Meanwhile, the English state barely had the resources it needed to wage war in Europe, never mind on the other side of the Atlantic.

The Anglo-French War of 1627–29, as it’s known to history, did feature a Quebec subplot. But the fighting in that sphere was conducted by independent contractors, not uniformed armies—which is to say, freelancing colonists operating on their own initiative, and fur traders (European and Indigenous alike) looking to exploit the geopolitical chaos as a means to improve their economic fortunes.

As we will see in future instalments, it is a trend that would continue long after this short war came to an end.

Our last instalment, The Dawn of Anglo Canada, concluded with a profile of two groups of English adventurers then sizing up French Canada in the mid-1620s.

Or, more precisely, British adventurers—as one of the contingents was Scottish.

The English venture was commanded by David Kirke, the eldest son of an English merchant based in the French port of Dieppe. The Kirkes had a close relationship with the Huguenot de Caen family, which (as some readers may recall from our twentieth instalment) had been pushed out of the officially sanctioned French fur trade as part of a larger power struggle between Catholics and Protestants.

Originally, the Kirkes and de Caens had planned on a joint trading voyage in the Summer of 1626, in defiance of the new fur monopoly established by Richelieu. But when war broke out between England and France, fresh opportunities arose. The Kirkes, though headquartered on the south side of the Channel, would now sail under a commission from the English Crown, with a mandate to root out the French and seize their colonial operations. What had once been conceived as a fur-trading expedition now became a state-backed quasi-military looting mission.

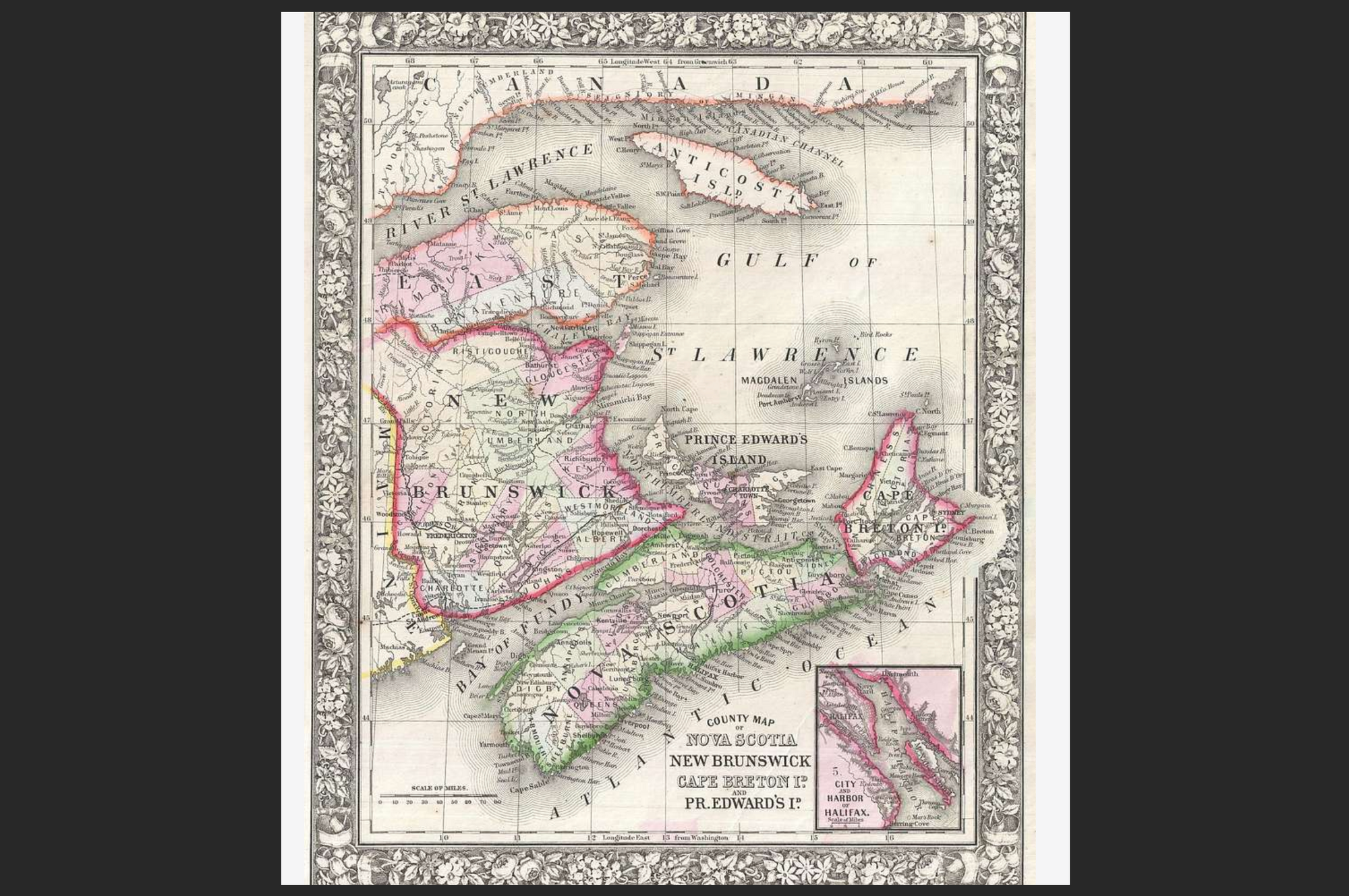

The Scottish enterprise was backed by William Alexander, a poet attached to the royal court who dreamed of Scotland taking its place among the great European powers by establishing a colony in (what Europeans considered to be) the New World. Britain’s Stuart kings—James I of England (r. 1603–25), then his son Charles I—granted Alexander title to what became known as Nova Scotia (New Scotland), a territory broadly overlapping with French Acadia. But to this point, Alexander had been unable to drum up the necessary funding and interest within Scotland to make the colony a reality.

As with the Kirkes’ operations, the outbreak of war offered Alexander a chance to rebrand his economic project as a military venture. The draw of plunder, combined with the possibility of displacing the French in Acadia by force, revitalised the Nova Scotian dream.

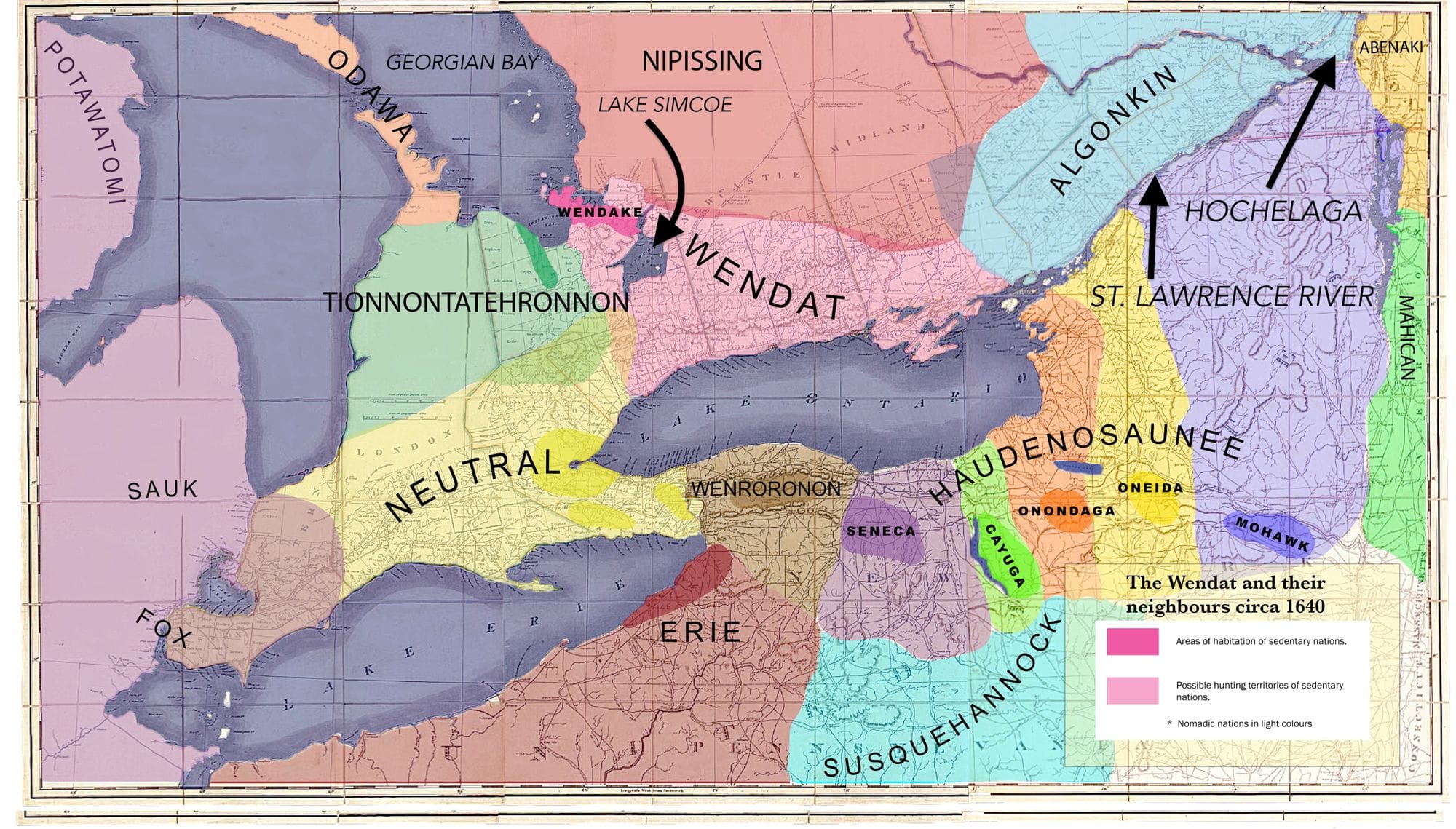

This dream struck Alexander and his backers as realistic because the French military position, both on the St. Lawrence and in Acadia, was quite weak. During his many years leading French exploration and fledgling colonisation efforts in Quebec, Samuel de Champlain’s focus had been to establish a stable trading and security relationship with important Indigenous groups, such as the Wendat, Algonquins, and Innu. While Champlain had generally been successful in this endeavour, it hadn’t required (nor yielded) any of the assets required to repel determined European invaders—such as a large standing military force, canons, and a well-developed system of fortifications.

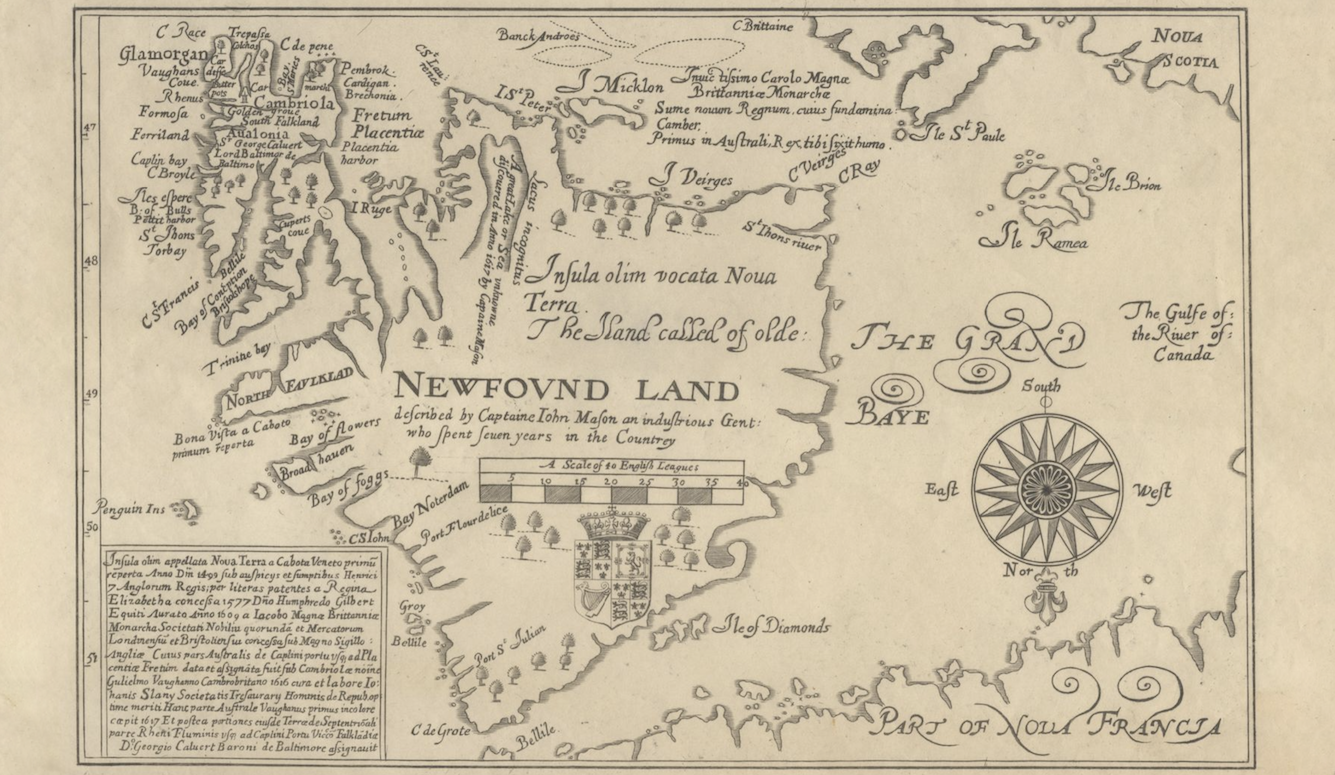

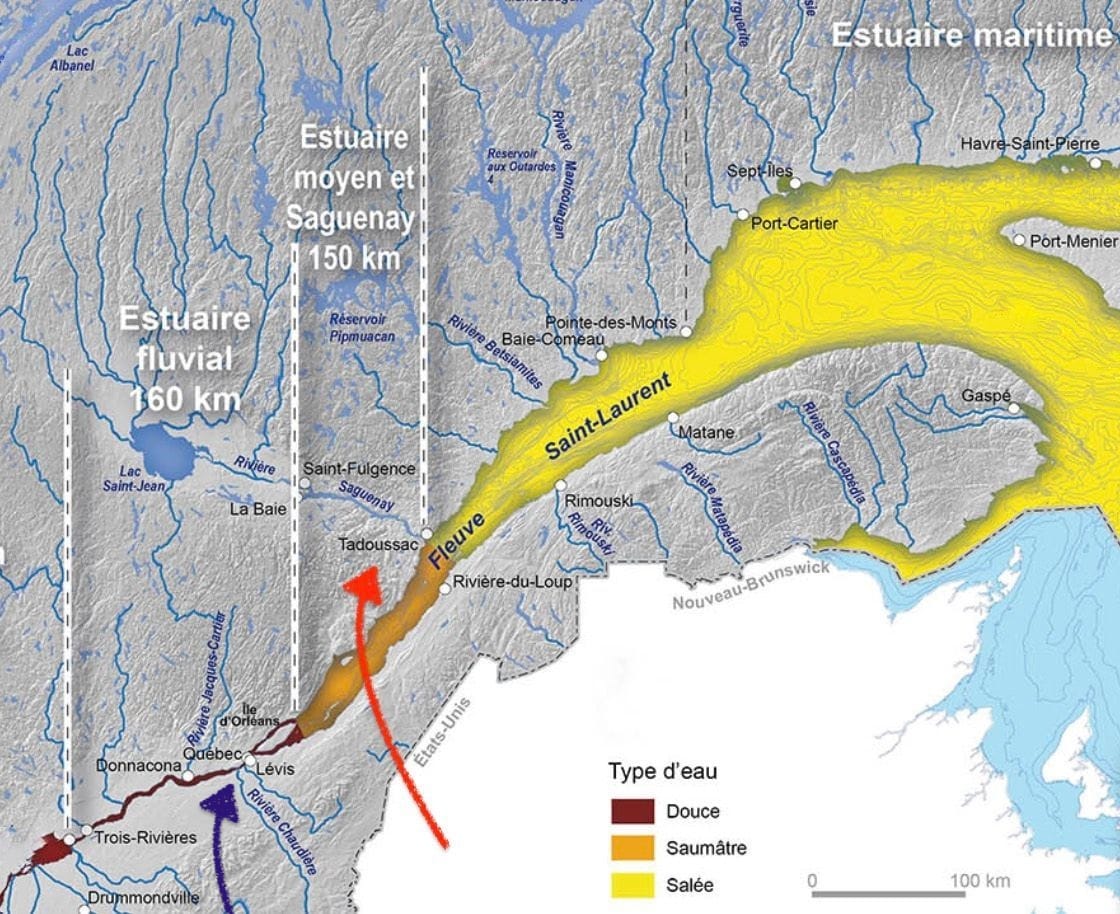

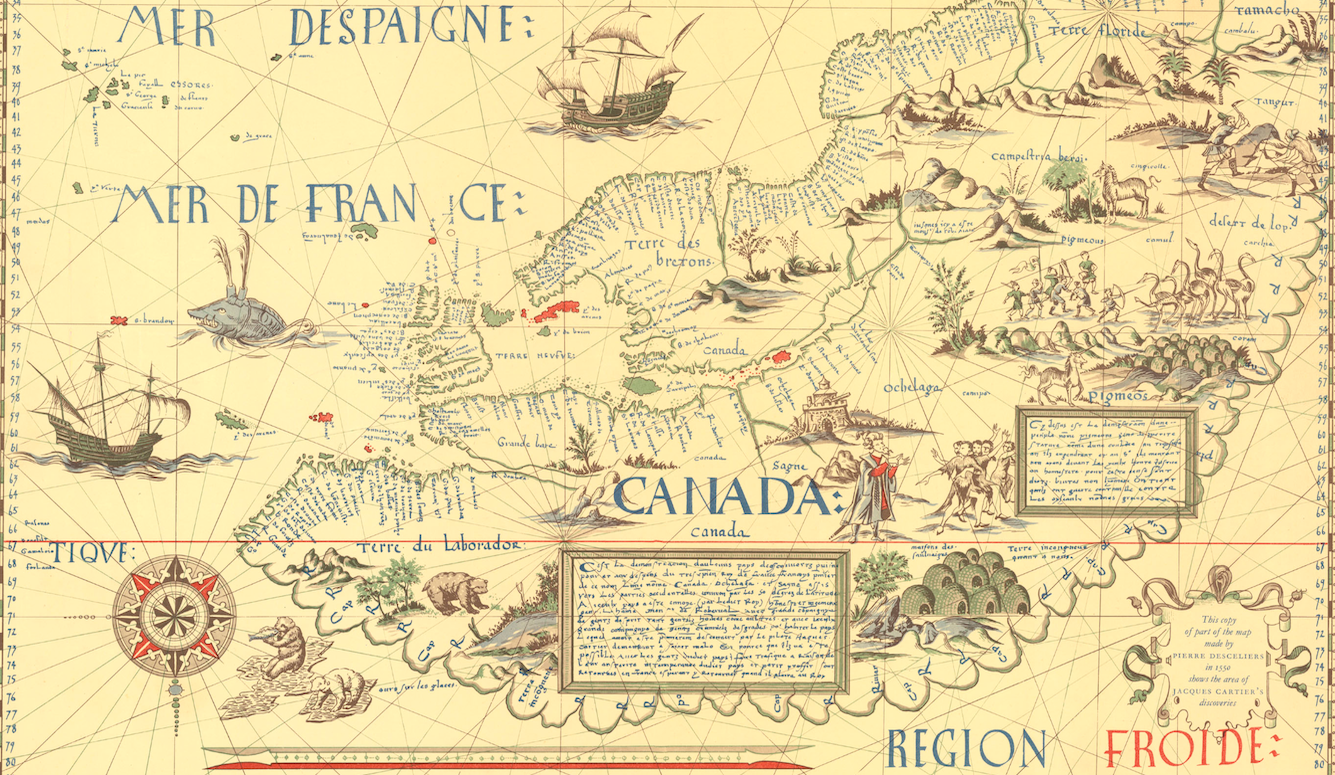

One advantage Champlain did enjoy was the strategically placed position of his main settlement at the site of modern Quebec City, which lies on a natural rise guarding the narrowing of the St. Lawrence River. (The word Quebec originates with an Algonquin term that means “narrow passage.”) Indeed, even a casual tourist visiting Quebec City can appreciate this fact merely by looking down on the St. Lawrence from the public park that sits on the spot known as Cap Diamant (a site destined to play an important role in the city’s history).

But Champlain didn’t have the manpower to defend it properly, nor the means to feed his settlers without regular cargo shipments from Europe. Even a modest force of enemy ships, Champlain realised, could easily starve Quebec into surrender by blockading his settlement.

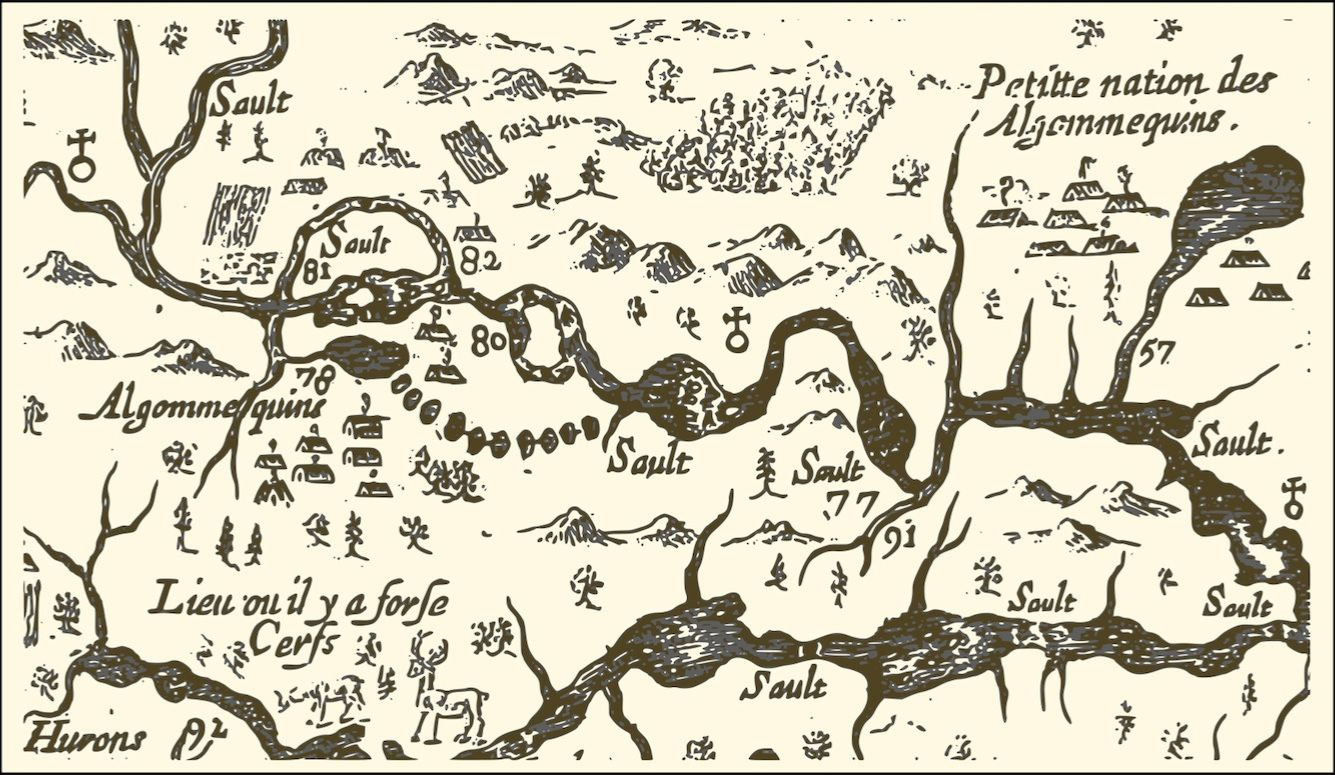

The other problem was Tadoussac—the venerable fur-trading site that sat 200 kilometres downriver (which is to say, to Quebec’s northeast), at the mouth of the Saguenay River fjord. The French had no permanent presence at what was still a strategically important regional hub. Rather, they operated a trading post that sat abandoned outside of the summer fur-trading season. In practical military terms, Tadoussac belonged to the local Innu, not the French.

And that was a real problem, as Franco–Innu relations were on the downswing—for reasons we’ve examined in previous instalments.

The French had originally relied heavily on the Innu as middlemen who wholesaled furs collected inland by Algonquin hunters. But the Innu role had been progressively sidelined as fur-trading operations began migrating upriver, toward Quebec and Hochelaga (modern Montreal).

This reversal of Innu fortunes betrayed the increasingly one-sided nature of the French diplomatic approach. Champlain, who’d formerly seemed more respectful and deferential, seemed to now treat the Innu as pawns. The French would need Innu help to resist any British invasion on the St. Lawrence, but there was reason to doubt whose side they’d be fighting on.

Unfortunately, our understanding of Innu politics is sketchy because the only surviving accounts come to us from French sources—which tended to report Innu activities through the simplistic prism of pro- versus anti-French attitudes.

During this period, French interactions with the Innu groups at Tadoussac were managed by a handful of chiefs—the two most important being named Erouachy and Cherounouy. As was typical in Indigenous political structures, these chiefs did not hold absolute or coercive power within their kinship groups, as would have been the case with, say, a European Duke. Rather, their status was contingent on their reputations as trustworthy leaders who would fairly redistribute the European goods exchanged in the fur trade.

Champlain harboured a personal distrust of Cherounouy, whom he suspected of encouraging the killing of two Frenchmen back in 1616—an event that, as discussed in past instalments, had strained Franco-Innu relations. Seven years later, Champlain received a warning that Cherounouy, in alliance with the Basques and other illegal European traders whose boats plied the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, was planning coordinated attacks on the French at both Quebec and Tadoussac. Cherounouy denied the charge, and the plot never materialised. But Champlain remained convinced that Cherounouy was organising an anti-French faction among the Innu, with the ultimate goal of destroying the French fur-buying monopoly and thereby restoring free trade (which is to say, more profitable trade—at least for the Innu sellers) with other European traders at Tadoussac.

Notwithstanding Champlain’s misgivings, however, the French officials who ran the fur-trading monopoly (which I’ve been referring to simply as the “Company,” but which then would have been referred to in France as La Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, La Compagnie des Cent-Associés, or La Compagnie du Canada) saw Cherounouy as an essential economic player, and so forced Champlain to reconcile with him in a formal ceremony. For the de Caen clan (which, by this point, hadn’t yet been ousted from its fur-trade leadership role by Richelieu), the priority was order and stability at Tadoussac. If paying homage to Cherounouy was the price that had to be paid, then so be it.

That ceremony only boosted Cherounouy’s status among his own people—who’d come to appreciate his efforts to deal forcefully with the French. Many Innu still nursed memories dating to the sixteenth century, before the French had established their fur-trading monopoly, when Tadoussac’s harbour would fill up with boats from many parts of western Europe every spring—and prices would get bid up accordingly. While the Indigenous societies encountered by Champlain were run on far more collectivist principles than those of Europe, Indigenous traders understood the capitalist principle of supply and demand extremely well.

Cherounouy’s colleague at Tadoussac, Erouachy, took a more subtle approach to his dealings with the French. (In colloquial terms, he might be seen as having played the “good cop” role, with Cherounouy as his bad-cop counterpart.) Indeed, he seems to have risen to prominence in part through his ability to act as a mediator who resolved the conflicts that men such as Cherounouy had exacerbated. In particular, he worked with Champlain to engineer a diplomatic resolution to the killings in 1616, and had informed the French about Cherounouy’s alleged plot to attack Quebec in 1623.

However, it would be inaccurate, or at least incomplete, to read Erouachy’s actions as simply pro-French. While he’d risen through the Innu political ranks thanks to his status as a mediator who was predisposed to work with—not against—the traders at Quebec, he was still very much a champion of Innu interests. And he likely didn’t see himself as a French partisan per se.

To complicate the political dynamic yet further, just as the Anglo-French war was breaking out, an ill-timed crisis to the south further complicated relations between the French and Innu.

To properly explain this part of the story (the run-up to which we covered in our twenty-first instalment), we need to revisit the situation in what is now upstate New York, where Dutch traders on the Hudson River were entangled in a war between the Mohawks and the Mohicans, who were fighting over access to European trade goods. The Dutch sided with the Mohicans, a choice they immediately came to regret when a group of Dutchmen were ambushed and killed by the other side.

By 1627, this intra-Indigenous war had been running for over two years, and the Dutch were still looking to extricate themselves from it. The Mohawk had made peace with the French and their Indigenous allies north of the St. Lawrence River in order to concentrate on the Mohicans. But the Innu were being drawn into the fighting, as Mohawk war parties harassed Innu traders heading down to the Hudson Valley to trade in Mohican territory.

Cherounouy (among other Innu) had contemplated formally joining forces with the Mohicans. His political program depended on the Innu maintaining access to multiple European trade networks (much as the Neutral Confederacy did out on the Niagara Peninsula), so as not to be reliant on Quebec, where the French were now using their monopoly power to dictate prices.

Ultimately, however, a conference of Innu chiefs decided against direct intervention on the Mohican side. The truce with the Mohawk (however shaky) was seen as too beneficial to toss aside.

Unfortunately for Cherounouy and the other Innu leaders, a handful of young warriors proved unwilling to accept that decision. In the spring of 1627, they launched an independent raid on a group of Mohawks, causing a serious diplomatic crisis.

As allies of the Innu, the French were in danger of being sucked into a renewed war that pitted the Innu and Mohicans against the entire Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the Haudenosaunee, or Six Nations, of which the Mohawk were the easternmost member) even as Champlain was supposed to be preparing for conflict with British attackers arriving from the east.

During the summer of 1627, the French and Innu organised a joint diplomatic delegation to assure the Mohawks that the truce was still in effect, notwithstanding the rogue actors who’d broken their truce earlier that year. Cherounouy represented the Innu, while the French sent Pierre Magnan, a trader who’d come to Canada to avoid facing murder charges back in France.

A month after the delegation departed, disastrous news returned north: The group had been ambushed by Mohawk warriors. Both Cherounouy and Magnan were tortured and killed.

Confusion ensued. Would Champlain now have to contend with a two-front war?

In fact, the incident did not signal a full-fledged Innu–Mohawk conflict. Rather, it had been the result of a personally motivated plot hatched by Cherounouy’s enemies (he had a few), who’d convinced the Mohawk that the chief’s diplomatic mission was actually a cover for espionage (with Magnan as collateral damage). However, those details would not become known in Quebec for another two years. And so when news of the massacre reached the St. Lawrence, it fuelled a panic within the settlement.

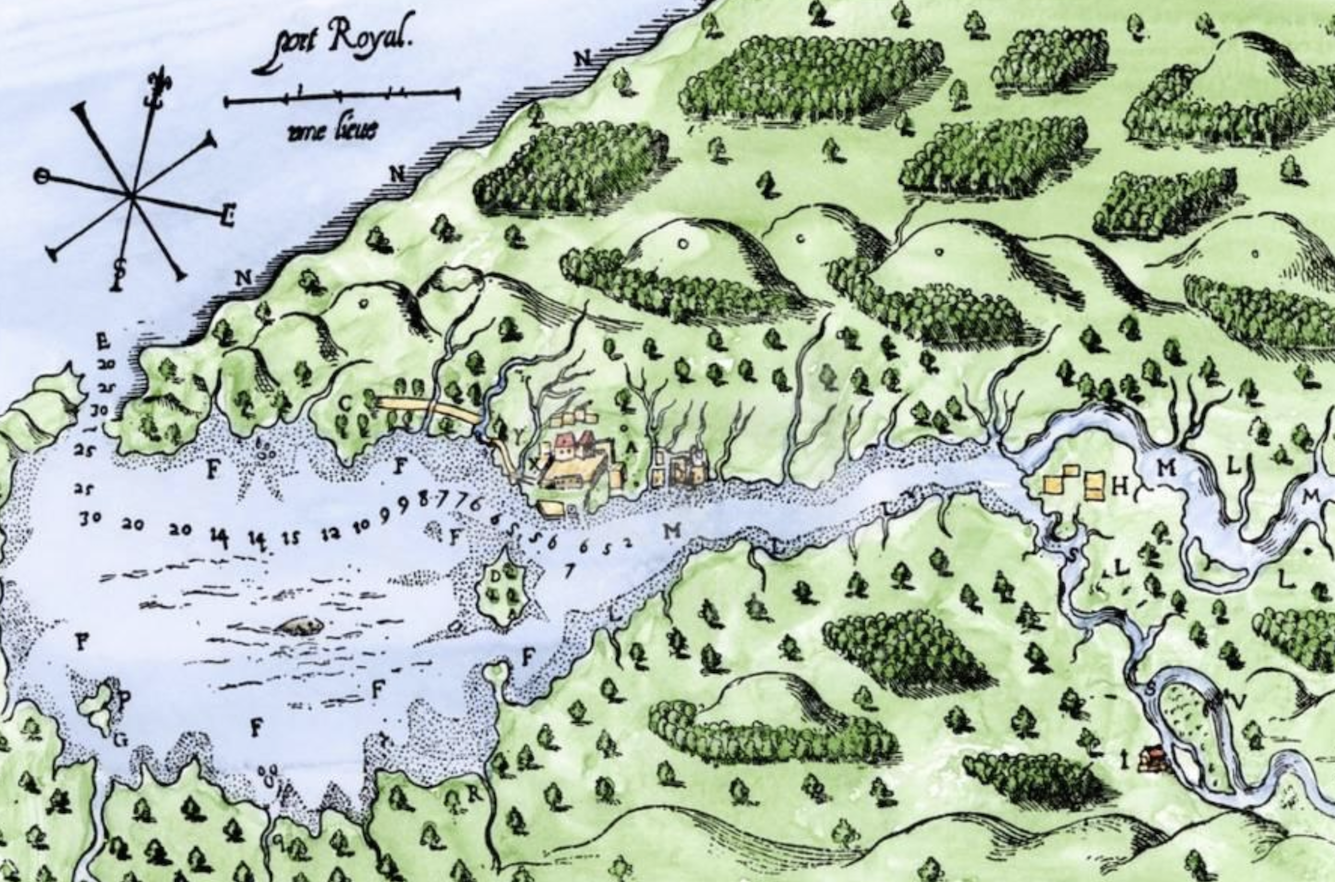

In Acadia, meanwhile, the French were even less prepared to face an invasion. Ever since the destruction of Acadian settlements and trading posts by the British in 1613 (a setback discussed in our seventeenth instalment), the French presence in the region had been minimal. In fact, by the 1620s, French Acadia wasn’t so much a colony, as a collection of seasonal fur-trading posts.

French claims in the region had cycled through the hands of several men, and were now held by Charles de la Tour, an adventurer and trader who’d first joined the French colony as a teenager. De la Tour and a handful of associates did remain in the region during the winter, but it’s probably more accurate to think of them as guests of the local Indigenous population than settlers in their own right. While traders still visited the ruins of Port Royal (the abandoned French colonial hub that had been destroyed by the British), de la Tour spent most of his time with a Mi’kmaq community at Cape Sable, an island off the southern tip of modern-day Nova Scotia.

From there, de la Tour organised an informal Franco–Mi’kmaq partnership, which did its best to enforce French control over fishing and fur-trading in Acadia. While this project enjoyed some success, throwing back a dedicated military attack was completely beyond de la Tour’s limited means. Unless he was reinforced, he told officials back in France, Acadia would fall to even a half-hearted British expedition.

Luckily for both Champlain and de la Tour, 1627 did not bring the invasions they feared, as neither the Kirkes nor William Alexander’s Scots were ready to move in force that summer.

Instead, both groups spent the winter of 1627–28 preparing—as well as waging a legal battle against one another. King Charles had originally given the Kirkes a broad commission to raid all enemy shipping, fishing, and colonial settlements in French North America. But Alexander objected that this conflicted with his own commission, granting him proprietary rights over Nova Scotia—an ill-defined territory that, he argued, covered both Acadia and (more dubiously) the St. Lawrence.

Out of these squabbles emerged a compromise: Putting aside his legal claims, Alexander joined with the Kirkes in a newly formed outfit known as the Company of Adventurers to Canada. The Kirkes retained their rights to whatever loot they could hunt down, but Alexander was given colonial jurisdiction over French Acadia and the trading post at Tadoussac—assuming they could seize these areas.

Thus reconciled, a joint fleet sailed across the Atlantic in the spring of 1628. The plan was for David Kirke (the eldest of the Kirke brothers) to command a set of ships that would raid the St. Lawrence, while Alexander’s Scottish settlers (about seventy in total) would break off and set up shop at Tadoussac.

A month later, in April, the French sent their own fleet. However, this one had a more civilian character. Despite the outbreak of war, Richelieu was determined to move ahead with his re-organisation of French Canada. Four hundred people (mostly prospective settlers heading to Quebec) were spread across four ships.

Charles de la Tour’s father, Claude de la Tour, was a late addition to this French voyage, bringing the supplies his son had requested (if not the military muscle). The Jesuits—who, as we’ve discussed, were a key part of Richelieu’s re-imagined New France—commissioned their own ship to tag along; as did a flotilla of private fishing vessels heading to Newfoundland. The whole expedition was commanded by one of Richelieu’s chief advisors (and the joint architect of his colonial policy), Claude Roquemont de Brison.

It was a historic venture: For the first time since the creation of Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval’s ill-fated colony in the 1540s (which we looked at way back in our sixth instalment), the French state was committing to a large-scale colonisation project—not simply authorising private investors to go out and settle land on their own dime.

For Champlain, it was the culmination of years of lobbying—which is somewhat ironic, in light of the disasters he’d soon be witnessing.

In mid-June, the French fleet arrived at Anticosti Island, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence. There, Roquemont received disturbing news: the Kirkes were already established at Tadoussac, and had even captured a few French vessels.

The French commander paused to assess the situation. His fleet consisted of transports rather than dedicated warships. And from what he was hearing, he’d be facing fearsome sea raiders if he proceeded to Tadoussac.

Roquemont’s first move was to try to send a message to Champlain at Quebec. One of the members of the expedition who’d been there before, a Frenchman by the name of Thierry Desdames, was dropped off on the Gaspé, with instructions to make his way upriver as quickly as possible. It was crucial that Champlain be made aware of the presence of the French colonial fleet, Roquemont told him. Quebec was entirely dependent on supply runs from France, and even the rumour that the Kirkes had blockaded the St. Lawrence might convince the Quebecers to surrender rather than starve.

But even if Champlain were notified that new supplies were on their way, that would only buy the French a little bit of time: The supplies had to actually get through to Quebec, and it wasn’t clear if that would be possible.

And so, just as soon as Desdames was dispatched on his messenger mission, Roquemont decided to brave the river, hoping to cloak his ships in heavy mists as he slipped past the Kirkes’ position at Tadoussac—not an implausible strategy considering that at this point, the St. Lawrence River is almost 20 kilometres wide.

The gambit failed, however. On 18 July 1628, the English caught sight of the French, and a battle ensued.

At first, the two fleets hammered away at each other to little effect, but the French quickly ran out of ammunition. Roquemont (one of the few men on either side to be wounded) surrendered. The majority of his would-be settlers were then shipped back to France, while Roquemont and a few prominent men (including Claude de la Tour) were taken back to England as hostages to be ransomed.

It was a disaster for Richelieu’s colonial policy. And making matters worse, it took place at a time when Franco–Innu relations seemed to be becoming volatile again, thanks to yet another deadly encounter.

Just before the arrival of the English and French fleets, Champlain was visited by Erouachy, the Innu chief who’d played an important role in mediating their previous dispute back in 1616.

Although the details are opaque to historians, this was probably a turbulent period within the Innu political world. The death of Cherounouy had thrown the Mohawk truce in doubt, and French control over Tadoussac looked weak. The geopolitical relationships that had defined Innu life for many years were suddenly becoming undone.

The immediate source of friction between Champlain and the Innu originated with the French explorer’s demand that the Innu bring to justice a man who’d recently killed a pair of Frenchmen—a deadly reprise of their original 1616 crisis.

Such disputes came up regularly during this period, as Europeans and Indigenous peoples had different ideas about how to deal with violent crime. For the French, the obvious course of action was to imprison or kill the offending parties. But in the Indigenous world, the proper way to resolve violent conflicts involving two otherwise friendly communities (as the French and Innu were supposed to be) was to offer gifts of condolence to the grieving party, or prisoners to replace the lives lost. Only enemies revenged blood with blood.

Making matter more complicated still, Erouachy (oddly) decided to stage his visit to Champlain alongside the Innu man rumoured to be responsible for the killings. But the Innu chief did his best to convince Champlain that it had in fact been Algonquins from the Ottawa River valley who’d committed the crime.

This may have been a face-saving falsehood—one that had the added benefit (from Erouachy’s perspective) of souring Champlain’s relationship with competing Indigenous trading partners.

Champlain, however, was in no mood for compromise. He read Erouachy’s prevarications as evidence of treachery. Instead of working out a settlement, the French colonial leader seized the suspected killer, and Erouachy returned to Tadoussac with Innu–French relations in an even more precarious state.

It was one of the rare times that Champlain acted in such an impulsive and short-sighted way. And the French would pay the price for it.

With Champlain having adopted what was (in the Indigenous world) a war-like posture, the Innu at Tadoussac had little reason to continue supporting the French. When the Kirkes arrived soon after, it seems, the Innu helped the English raiders seize control of the trading centre. Far from aiding in the French resistance, they traded freely with the Kirkes and their associates all summer. As a result, the soon-to-be starving settlement of Quebec was at the mercy of the British.

Champlain’s one hope for salvation was that David Kirke had no intelligence on the situation at Quebec. The English raider knew that Champlain had been improving the settlement’s fortifications over the previous years, but he didn’t really know how much progress had been made, nor how many men were available to man the walls.

This was important because, while the English force was superior to that of the French, the English ships had none of the specialised equipment necessary to mount an amphibious assault against prepared defences, nor lay siege to a fully-manned fortress.

Kirke therefore enlisted the support of a group of Basque traders who were taking advantage of the (now) free market at Tadoussac, commissioning them to send a message to Champlain, demanding his surrender. The Frenchman’s response, and any report the Basques might provide about conditions at Quebec, would guide his actions from there.

Despite his desperate situation, Champlain put on a brave face and sent the Basques back down river with what was essentially a bluff. And it worked: The Kirkes returned to Europe at the end of the 1628 trading season without moving against Quebec.

Although they’d missed an opportunity to capture (or at least destroy) Champlain’s main base, they celebrated their voyage as a success. And with good reason, as they’d captured the largest French supply fleet ever sent to the St. Lawrence, then dominated the trade at Tadoussac all summer. Alexander’s Scots would remain at Tadoussac over the winter, and prepare for a 1629 trading season that they hoped would be even more successful.

Back in Europe, on the other hand, things were going less well for the English. The architect of England’s war strategy—a favourite of Charles I named George Villiers, who’d been made Duke of Buckingham—failed to land an English army in support of the Protestants at the southwestern port of La Rochelle after they’d risen up against the French Crown. In fact, Buckingham failed so disastrously that he would later be stabbed to death by one of his own naval lieutenants. (The assassin, one John Felton, was arrested as a murderer—but such was the widespread hatred of Buckingham that his death provoked public celebrations.)

After Buckingham’s death, English policy shifted. The war with France had been his project as much as the King’s, and (in retrospect) had been a mistake. Charles realised that war was expensive, and his resentful subjects were increasingly bold in challenging the Crown’s authority to levy war taxes (part of the larger fiscal impasse that would eventually lay the groundwork for the English Civil War—but we digress). In the winter of 1628–29, Charles sent out peace feelers to the French, searching for a face-saving way to end the conflict.

Canada—to this point, something of a sideshow—now took on greater significance in European geopolitics. As the one theatre in which the English hadn’t failed, it provided assets that Charles might offer at the bargaining table as a means to offset concessions he’d be forced to offer in regard to Europe.

For the Kirkes and William Alexander’s Scots, this was bad news—which they didn’t intend to take lying down: The Company of Adventurers to Canada was determined to entrench itself in Quebec and Acadia so thoroughly that it couldn’t be easily displaced by the stroke of a pen back on the other side of the Atlantic.

Luckily for the Adventurers, Quebec was in no position to resist. Champlain and his colleagues had avoided certain defeat in 1628 only through bluff and luck, and the intervening months had done nothing to improve the French situation. In the absence of new supplies arriving from France, the settlers at Quebec faced a food crisis.

Desperate, Champlain turned to his Indigenous allies—though his options were somewhat limited. By this point, it wasn’t entirely clear whether the Innu were friend or foe, so seeking aid from that corner was problematic. One group of Quebecers tried to winter among the Abenaki, French-allied Algonquin-speakers who lived near the mouth of the St. Lawrence in modern-day New Brunswick. But they ended up being apprehended by the Kirkes before the English headed home.

Meanwhile, France’s Indigenous allies to the west, the Wendat in modern-day Ontario, were able to provide only limited help. The 1628 trading season on the St. Lawrence had been one of the worst since the Laurentian Coalition had been forged, as a drought had cut into the corn surplus that the Wendat used to fuel their trading network. Moreover, the handful of Wendat traders who did travel to the St. Lawrence found the French had little to offer: The supply fleet captured by the British had carried off Quebec’s trade goods along with its food.

The Wendat did agree to help relieve the burden on Quebec’s food stores, however, by taking as many as twenty Frenchmen back upriver for the winter—the largest group ever to be hosted in Huronia.

This returning convoy also brought instructions back to the Huronian-based Jesuits that their leader, Jean de Brébeuf, was to close up shop and return to Quebec. The fate of French Canada might be decided in the next few months. Staying in Huronia long-term might mean being cut off from the rest of the French world.

Quebec managed to hold together through the winter of 1628–29, manned by a skeleton crew whose members survived on root vegetables and cornmeal. And when Brébeuf appeared on the St. Lawrence in the spring, he brought with him a desperately needed contribution of corn from the Wendat. But this only bought the French a bit of time. Even if the English didn’t attack, surviving another year without a supply run from France was impossible.

Erouachy once again visited Champlain soon after, in April 1629, and offered to broker a deal. His group of Innu could escort the French to the Atlantic coast, where they’d live out the year under the hospitality of the Abenaki. In exchange, Erouachy demanded the release of Champlain’s prisoner—the man whom Champlain held responsible for the killings of 1627.

Champlain stubbornly refused, putting the final nail in the coffin of Franco–Innu co-operation.

Around the same time, his small group of Frenchmen in Quebec fell into a bitter argument over their meagre food stocks. Champlain, the missionaries, and the traders each claimed authority over how to divvy up the corn. Their infighting was interrupted in July only when European ships were sighted on the St. Lawrence.

As everyone had feared, these weren’t French supply ships, but another English war fleet.

At this point, I’ll back up the narrative so that we can catch up on the Kirkes—who’d set their sights on Quebec—and Alexander’s Scots, who were focused on Acadia.

To take the Scots first, French Acadia had been fortunate to avoid the fighting of 1628, when Alexander concentrated his efforts on securing Tadoussac. But now, the Scots were intent on planting as many settlers as possible in Acadia—or, as they were already calling it, Nova Scotia.

Alexander’s son (also named William) led an expedition into the Bay of Fundy, with the ultimate goal being to rebuild Champlain’s abandoned settlement at Port Royal (see instalment number twelve). On the way, he stopped to see Charles de la Tour at Cape Sable.

But the Scots did not come to Charles as conquerors. Rather, they arrived with a proposition for the Frenchman. And delivering that proposition was none other than de la Tour’s own father, Claude, who was technically a Scottish prisoner.

As detailed above, Claude had been captured the previous summer at Tadoussac, along with the French supply fleet. But since then, the elder de la Tour had come to an arrangement with his captors. The French had never provided any support to his son’s Acadian enterprise, he explained. In fact, there was still an outstanding legal dispute in Paris over who actually owned Acadia. Might a new partnership with the Scots not serve everyone’s interests?

At Sable Island, however, the younger de la Tour was having none of it, preferring to persist in his defence of French Acadia with a ragtag force of marooned Frenchmen and Mi’kmaq warriors.

Alexander was disappointed, but didn’t see de la Tour’s motley crew as a threat to his mission. The Scots continued on to Port Royal, Champlain’s old 1613-era stomping grounds, which Alexander began setting up as the headquarters of his now-finally-realised colony of Nova Scotia.

Meanwhile, another group of Scots established a foothold on the island of Cape Breton, at the northeast corner of modern-day Nova Scotia. The French had been trading in the area for generations, but the Scottish colonists saw it as a prime target for more thorough development—especially since it had strategic value, being positioned at the southern entrance of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

These Cape Breton settlers were led by James Stewart, Lord Ochiltree—a heavily indebted noble who saw colonial adventurism as the solution to his financial woes (a story we’ve heard before, in both its English and French variants). Ochiltree had sunk himself yet further in debt to buy out Alexander’s rights to Cape Breton. And on 1 July 1629, he and about sixty fellow Scots landed at a natural harbour on the eastern extremity of the island. Ochiltree named their settlement Fort Rosemar.

There were now more Scots in Acadia than Frenchmen; and without aid from home, it wasn’t clear what Charles de la Tour could do about it.

The French at Quebec were in an equally precarious position. David Kirke returned in 1629, and once again captured the annual French supply run. No matter how brave a face Champlain was putting on things, the Kirkes knew that Quebec had to be on the brink of starvation.

Leaving nothing to chance, the Kirkes recruited Jacques Michel, a French pilot with plenty of experience navigating the river approaches to Quebec—one of the many men who’d been marginalised by Richelieu’s overhaul of the colony.

And this now brings our story back to where we left things in Quebec—with Champlain and the other hungry, squabbling Frenchmen watching Kirke’s armada sail toward their settlement.

Champlain recognised that further resistance would be futile. On 20 July 1629, he surrendered Quebec to Thomas Kirke (acting in the name of his older brother, who’d by now established his headquarters at Tadoussac). A group of 150 Englishmen took possession of Quebec and quickly replaced the Catholic missionaries with a Protestant minister. This was no raid: It was designed to be a permanent occupation.

Champlain and a few others were taken into custody, while the rest of the Frenchmen were left to fend for themselves. A half-Basque, half-Mi’kmaq trader named Juanchou ferried some refugees to the coast, where they’d hopefully find fishermen willing to take them back to Europe.

The first stop for Champlain was Tadoussac, where he met with David Kirke. A more resilient French supply convoy had recently arrived, Kirke explained, and the English were hoping to resolve the ensuing naval standoff without shedding blood. There was no longer a French settlement at Quebec to supply. And Champlain, being living proof of this fact, was in a good position to broker a settlement.

The French fleet, however, brought game-changing news from Europe: England and France had signed a ceasefire. And so the Canadian theatre had once again become an afterthought to the diplomats in Paris and London. Their truce, signed on 14 April 1629, mandated an immediate halt to military actions, and recognition of territories held by either side at the moment of the agreement.

Since the fighting in Europe had taken place almost exclusively at sea, and so involved no occupation of enemy territory, this boilerplate treaty language had little effect. But it created an awkward problem for the English and French in Canada: Technically, the Kirkes had conquered Quebec three months after the truce, throwing their possession of the settlement into diplomatic limbo.

Champlain recognised that he had a strong legal case that Quebec ought to revert to his control. Kirke, on the other hand, refused to give up his prize, and argued that the mere rumour of a truce, relayed by French sailors, was not legally binding. The fate of Quebec would be determined by diplomatic haggling back in Europe.

But for now, the conquest of Quebec was a military reality. That outcome was not the result of English imperial policy, but rather had been engineered by profit-seeking adventurers. Ironically, their campaign was helped along by decisions made in both Paris and Quebec: Richelieu’s top-down overhaul of New France alienated key players within Canada, some of whom shopped their services to the newcomers; and Champlain’s mismanagement of the Innu relationship handed the invaders a beachhead in Tadoussac.

Although the Kirkes secured Quebec in the name of Charles I, disaffected French subjects were involved in both their campaign and the new nominally British regime established at Quebec. This was not an imperial contest where men were motivated by loyalty to King and Country: Events were determined largely by local, Canadian interests.

It didn’t take long for a certain continuity to emerge between French and English Quebec. The translators, who’d managed Franco-Indigenous relations for many years, quickly adapted to the new leadership. In part, this was due to the shabby treatment they’d lately received from the French authorities: Richelieu and Champlain had followed a conscious policy of replacing the translators with Jesuit missionaries.

Étienne Brûlé—remember him?—returned to his old position as a vital link between the European and Wendat worlds. And Nicolas Marsolet, a long-time translator embedded with the Innu, helped forge a relationship between his old friends and his new British bosses. The speed with which these old relationships were renewed led cynical French observers to wonder what role such men had played in Quebec’s downfall.

Despite taking on these skilled recruits, however, the Kirkes failed to arrest the decline in the St. Lawrence fur trade. While 1630 saw a large increase in trade, this proved to be a short-term blip caused by the Wendat’s stockpiling of furs during the previous two years. The next year’s trade declined to war-time levels.

In part, this was due to events to the south. By 1628, the Mohawks had successfully supplanted the Mohicans on the Hudson River. With their access to Dutch trade now assured, Haudenosaunee raiders were now less worried about abiding by their truce on the St. Lawrence. And in the summer of 1629, they destroyed a joint Algonquin/Innu settlement upriver from Quebec that had often acted as a trade hub.

The problems were exacerbated by English policy at Quebec. Unlike the French, the new regime didn’t bother patrolling the St. Lawrence upriver from Quebec—a short-sighted attempt to reduce costs. Even with the return of plentiful European goods to the marketplace, Wendat traders became discouraged from making the trip to the St. Lawrence by the threat of Mohawk attack.

The return of Mohawk raiders (and the Haudenosaunee more generally) to the St. Lawrence would be a defining feature of the next two decades of Canadian history—and is, in part, a legacy of the disruption caused by war and the English occupation.

The English were discovering that the system Champlain had developed went far beyond commerce. Without the diplomatic and military components of the Laurentian Coalition, the English found it difficult to replicate French success.

The Scots in Acadia faced even greater challenges. The new settlements on Cape Breton and at Port Royal existed in the same legal limbo as English Quebec. And with hostilities in Europe concluded, French vessels were once again able to cross the Atlantic safely. Some of the investors in Richelieu’s reformed colonial company weren’t willing to wait for the diplomats to secure their rights. And Acadia offered their best opportunity to regain a toe-hold in North America.

These French colonialists raised money for a fleet to roust Ochiltree’s Scots from Cape Breton. This goal was achieved relatively easily, and the Scottish settlement was dispersed. Upon Ochiltree’s arrival back in Europe, he did his best to turn the matter into a diplomatic incident, to be taken up in the complex ongoing peace negotiations that followed the original 1629 ceasefire. But this lobbying campaign was undermined when Ochiltree was caught up in a treasonous plot to unseat Charles I from the Scottish throne. The King threw the Scottish noble into Blackness Castle, and was not inclined to do him any favours in Acadia.

The William Alexander father-and-son duo didn’t fare much better at Port Royal. In 1630, a French supply fleet landed at Charles de la Tour’s base at Cape Sable, as de la Tour had gained associate status in Richelieu’s colonial Company. The balance of power in Acadia thereby swung in de la Tour’s favour—especially given that the Scots at Port Royal had suffered through a bitter winter during which half the settlers died.

By this point, the Alexanders were disillusioned with the costs and difficulties of Canadian colonisation. Rather than press for recognition of their Nova Scotia holdings, their goal now was to extract compensation for surrendering their rights to a lost cause.

As for Champlain, he’d soon find himself in England—arriving there as a prisoner of war. After receiving his release, he secured the French ambassador’s assistance in agitating for the return of Quebec in the final treaty still being hammered out.

That turned out to be a lengthy process. After the signing of the initial truce in spring 1629, the diplomats spent almost three years haggling—eventually coming to a settlement in March 1632, known as the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (not to be confused with the four other treaties signed in the same Paris suburb).

The delays were the result of King Charles conducting parallel peace talks with both the French and the Spanish, trying to play one side off the other. The resulting three-way chess game was complicated; but, despite losing the war everywhere but in the minor Canadian theatre, the English King was able to score a relatively beneficial peace.

Eventually, Charles agreed to return Quebec to France and pull out of Acadia, formally recognising French control over the St. Lawrence. In exchange, King Louis XIII agreed to pay the remaining balance of the dowry he owed Charles from his marriage to his sister, Henrietta Maria. (That match was supposed to have been the linchpin of Buckingham’s Anglo–French alliance, but the two supposed allies had fallen into war before all of the money had changed hands.)

For the Kirkes and the Alexanders, it was the outcome they’d feared: The English King used their successes in Canada as mere bargaining chips to cash out his losses in Europe.

News of the peace arrived on the St. Lawrence in the summer of 1632. Quebec’s English masters stayed on long enough to reap the modest benefits of the season’s Wendat convoy, then closed up shop. Their three years on the St. Lawrence had served as a learning experience that had been more frustrating than profitable. Managing the Canadian fur trade required diplomatic skill; indigenous cultural knowledge; and environmental adaptability—assets the English, thus far, still lacked.

Meanwhile, it’s likely that the remaining Scots at Port Royal were downright happy when the French arrived to take over their settlement. Passage home aboard a French ship was preferable to another winter on the Bay of Fundy.

All this left Cardinal Richelieu right back where he’d left off in 1627—still intent on remaking France’s colonial project according to his own administrative and religious blueprint. In a sense, this would be a New New France—one that would soon become unrecognisable when compared to the version that preceded it.