Nations of Canada

Land of Frost and Scurvy

In the sixth instalment of an ongoing Quillette series on the history of Canada, Greg Koabel describes France’s disastrous first attempt to set up a permanent colony in Quebec.

What follows is the sixth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized project adapted from transcripts of Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name, which began airing in 2020.

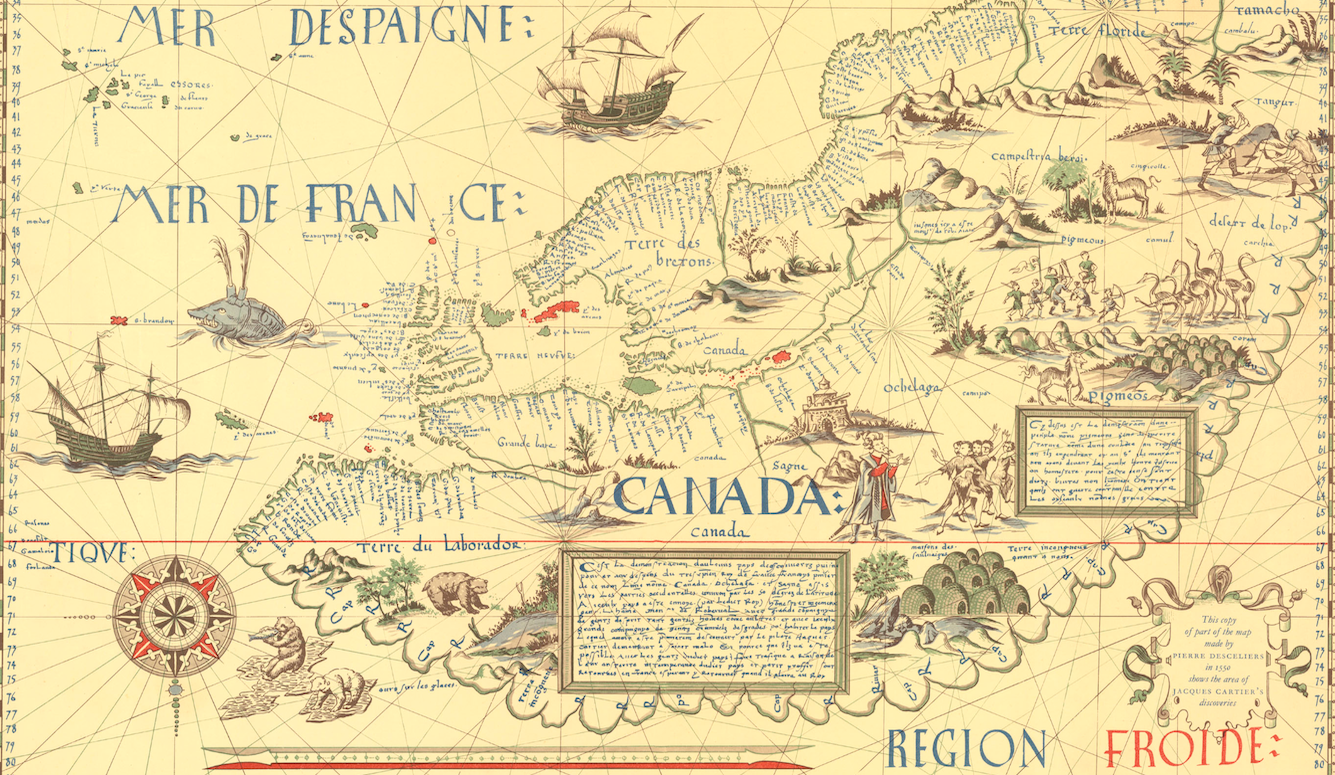

In the last instalment, we left off in the winter of 1534–35, with Jacques Cartier preparing to follow up on his voyage into the Gulf of St. Lawrence the previous summer.

This second voyage was better funded and more ambitious than the first. This time, France’s King, Francis I, set Cartier up with three ships, and a collective crew of 112 men. More importantly, the voyage was intended to last for a full year, to allow Cartier the time needed to push through the great waterway. Cartier was confident that wintering along the St. Lawrence would be feasible. His expert guides—Domagaya and Taignoagny, two Iroquois brothers from the village of Stadacona, whom he’d abducted on his first voyage—assured him that the whole area was well-populated.

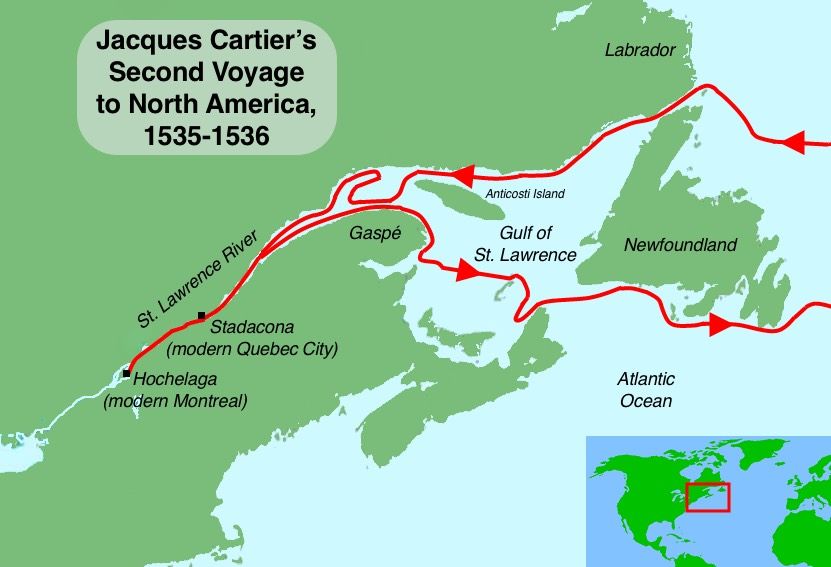

Cartier departed on May 19th, 1535. This time, however, the crossing was not nearly as smooth. The ships were battered and separated by powerful storms. It took more than two months for the three ships to reunite in the Strait of Belle Isle, which separates Labrador from Newfoundland. By then, it was late July, around the same date Cartier had started heading home the year before.

Likely at the urging of Domagaya and Taignoagny, Cartier sailed straight for the Gaspé peninsula, hoping to once again meet the Stadaconans on their annual voyage to the sea. But they were nowhere to be found. It’s likely that the Stadaconans had only recently returned home.

From there, Cartier sailed north, and sighted Anticosti Island. The Stadaconan brothers informed Cartier that this was the beginning of the great waterway. As it was August 10th, Cartier named it after the saint associated with that day on the Christian calendar—St. Lawrence.

As Cartier moved west, he was astounded by the width of the channel, but somewhat disappointed that his ships were clearly moving into fresh water. This was a river, not an ocean strait. Still, Cartier did not give up hope. This was the greatest and widest river he had ever seen—it was not unreasonable to think that it provided a connection to the riches he sought. His young guides assured him that there was a great sea at the other end.

In early September, the expedition met a group of canoes—Iroquois men fishing in the river. Domagaya and Taignoagny celebrated: These were their fellow Stadaconans, whom they had not seen since being taken to France a year earlier.

In fact, the village—near the site of modern Quebec City—was less than a day upriver, where the St. Lawrence narrows. (“Quebec” comes from an Algonquin word meaning “narrow passage.”) The Stadaconans were overjoyed, especially the boys’ father, Chief Donnacona. Although everyone had hoped that the French would return with their two hostages, there must have been a significant amount of confusion and anxiety about the events of the previous summer. Those anxieties would only have been heightened when the French did not show up on the Gaspé 12 months later.

Now, those tensions were released in a joyful exchange of gifts between the Stadaconans and the French.

But despite the warm welcome, Cartier remained cautious. He anchored his ships in the river nearby, and he and his men rarely came ashore. When they did, they armed themselves, causing some initial irritation among the Stadaconans. Such behaviour suggested distrust of their hosts, a rather rude response to Stadaconan hospitality. But Domagaya and Taignoagny helpfully explained that this was European custom. In France, everyone walked around with swords.

This explanation satisfied the Stadaconans, but Cartier’s wariness was impossible to miss (and struck them as anti-social). Cartier still refused to meet on land unless it was away from the village, in small groups.

Donnacona and the other leaders who met with Cartier were even more troubled when they found out what the French explorer’s mission entailed: Eager to get moving before winter set in, Cartier (through his translators—Donnacona’s sons, who’d learned to speak French during their year in France), expressed a desire to press on further upriver.

This was not what Donnacona had hoped to hear. Likely, the Stadaconans assumed that Domagaya and Taignoagny’s time in France had been the first step in formalizing a trade alliance. Ideally, the French would now leave some of their own men with the Stadaconans, building further trust. The exchange of hospitality would bind the two peoples together and mutually beneficial trade could begin, in accordance with traditional Iroquois custom.

But Cartier’s desire to press upriver himself was something else entirely. The danger was that Cartier would bypass the Stadaconans with his future trade relationships, after making formal alliances with other Iroquoian peoples to the west. This could include Stadacona’s rival, Hochelaga, which lay a few hundred kilometers upriver at the site of modern Montreal.

The lateness of the season only added to the problem. Where the French spent the winter was of crucial importance. There was no greater expression of a strong trade alliance than wintering in your partner’s territory. This would become a key element of French relations with Indigenous peoples in the century to follow, though Cartier was then ignorant of its significance. The possibility that the French might spend the winter in Hochelaga alarmed the Stadaconans.

Unfortunately, we don’t have any direct evidence about how the Stadaconans dealt with this political problem. We can only speculate on their side of the story based on Cartier’s (uninformed) account of what was going on. But it seems apparent that Chief Donnacona developed a subtle strategy to dissuade the French from their goal, without angering or alienating these potential allies.

His first tack was to deprive Cartier of his interpreters. Donnacona convinced his sons to refuse to accompany Cartier any further west. This was probably not hard. Domagaya and Taignoagny had only just returned home after more than a year abroad. And there was no guarantee that they would return from this new trip upriver. The French clearly valued the two brothers as interpreters; and Cartier, at least, seemed to assume that their loyalties were now with the French rather than Stadacona.

However, the prospect of continuing on without translators did not seem to faze Cartier one bit. He’d been able to establish relations with the Stadaconans without a translator. And so, he thought, he could repeat the exercise upriver if he had to.

Donnacona turned to a tactic that would become familiar in future Franco-Indigenous relations—the spread of salacious rumour. No doubt picking up on Cartier’s inherent fears, a group of Stadaconan shamans predicted death for any Frenchmen who pressed on upriver. The nations to the west were violent and savage, they said. It was far safer for the French to stay put, and allow the Stadaconans to manage trade with the deadly warriors who lay upriver.

But this, too, failed to dissuade Cartier. He dismissed these predictions as superstitious nonsense, and reiterated his need to push west.

Finally, accepting that Cartier could not be talked out of his mission, Donnacona attempted to strengthen the alliance with the French before their captain left. A meeting between the Hochelagans and the French might not be a disaster for Donnacona and his people—but only if the Stadaconans could ensure their relationship with the Europeans was strong.

In order to achieve this, Donnacona suggested another exchange of people. He offered Cartier three children (two boys and one girl). But Cartier refused to leave any of his crew with the Stadaconans, and instead reciprocated by offering swords and copper washbasins. These were not insignificant gifts, but they signified that Cartier was rejecting Donnacona’s offer of a formal trade alliance.

On September 19th, Cartier headed upriver with part of his crew, leaving the rest to build a rudimentary fort outside Stadacona. Whether he knew it or not, he also left an anxious village, still uncertain of whether the French represented a threat or an opportunity.

On October 2nd, Cartier arrived at an island in the middle of the St. Lawrence. His pilots were not confident that the ships could continue any further, so Cartier and a handful of men got in a small boat and began rowing to shore. While approaching the southeast side of the island, at a site near the 20th-century bridge that now bears Cartier’s name, the French saw a large group of men and women lining the coast to observe them. Based on the information he had gleaned so far, Cartier presumed (correctly) that he’d found Hochelaga.

Cartier estimated that the crowd was at least 1,000 strong, and so halted. He and his men spent the night in their boats, while the people on shore lit fires and seemed to hold some kind of ritual or celebration.

The next day, Cartier decided he would have to take his chances and make contact. Once ashore, he and 25 men immediately encountered a small group of Hochelagans. As had been the case with the Stadaconans, Cartier’s men were greeted warmly and escorted to the village.

Hochelaga was different from Stadacona. Where the hybrid Stadaconan economy was somewhere between the corn farmers of the Great Lakes and the Algonquin hunter/gatherers of the Canadian Shield, Hochelaga was similar to the dedicated farming communities that Europeans would later observe among the Wendat or the Iroquois. Cartier was impressed with the fields of corn the welcome party passed through on the way to the village.

The village of Hochelaga itself was also different. Here, the need for security had driven many smaller villages to consolidate into a single unit—meaning that Hochelaga was larger, and defended by a wooden palisade. Cartier estimated a total of 50 longhouses and upwards of 2,000 residents.

In the centre of the village, Cartier and his men were treated to a formal ritual of welcoming. Or, at least, that’s what Cartier assumed. Without translators, this was all guess work. Cartier responded with an indecipherable ceremony of his own, including a long speech, a reading from the Bible, and gifts that he presented to anyone who seemed like an authority figure.

Once this was completed, Cartier managed to express (through awkward gesture) his interest in what lay further up the river. This led to a trek to a plateau that offered a good view to the west of the island.

There was good news and bad news for Cartier. The bad news was that his pilots had been right to be wary: Immediately up-river from the island was a set of rapids (later known as the Lachine Rapids) that would be impossible for anything larger than a small boat to pass through. Further navigation upriver would be complicated, and certainly not possible before winter.

But there was good news, too. Cartier’s Indigenous guides pointed to his gold-encrusted dagger and then gestured past the rapids. Cartier took this to be confirmation of what the Stadaconan brothers had told him: A civilization of great wealth was accessible via the St. Lawrence. Likely, the Hochelagans were indicating an ancient trade route, by which copper (which could be found on open ground around Lake Superior) made its way east.

A second bit of good news was also revealed. At the western end of Hochelaga’s island, another impressive river fed into the St. Lawrence. This was the Ottawa River, an alternate, northern path to the Great Lakes. Hochelaga was strategically poised on the two great highways that cut across the land from east to west. Cartier had a lead on another possible path to the Orient.

Cartier contemplated this new information. It had been a nervy day for him, considering his usual reluctance to place himself at the mercy of locals. In fact, in their haste to explore the island, Cartier and his men had refused to join a feast in their honour. And they now rushed backed to their boats rather than spend the night within Hochelaga’s palisade.

The entire episode took place over a single day. As with the Stadaconans, the Hochelagans showed little outward sign of irritation, but such repeated rejections of their hospitality did spread confusion and mistrust.

Once Cartier re-joined his ships, he sailed back to Stadacona. Aided by the river’s current, he arrived on October 11th.

On the surface, all seemed well. The men Cartier had left behind were safely huddled inside a makeshift fort, protected by a cannon dragged off one of the ships. For their part, the Stadaconans were happy to see Cartier back so soon. The danger of a Hochelagan alliance had apparently been averted. Cartier prepared for winter, confident that, in the spring, he would have more time to explore further west.

However, things quickly turned sour.

First of all, the French badly underestimated how bitter the winters on the St. Lawrence could be. The Europeans who’d been fishing off Newfoundland for decades were purely seasonal visitors, and so had only a limited understanding of Canadian winters. Cartier knew by his navigational measurements that they were at roughly the same line of latitude as the south of France. But western Europe is warmed by the effects of the Gulf Stream, making any comparison with North America misleading.

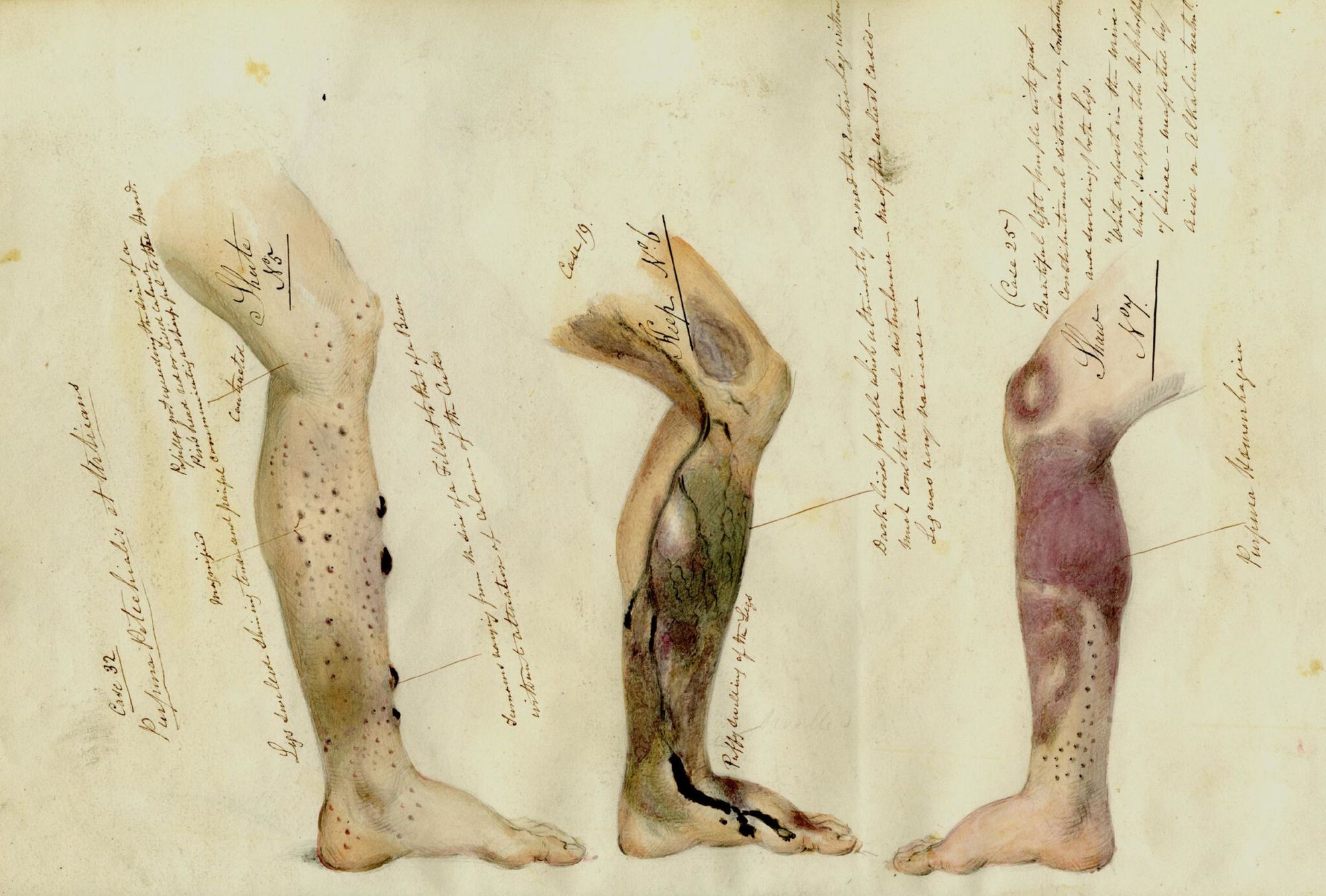

The hastily constructed dwellings the French had thrown up were poorly insulated, and many of the beverages the French had brought with them froze in their casks. Worse still, the French found their provisions inadequate. Quantity was not the problem, as they had brought plenty of grain. The problem was that the French had little experience with expeditions of such length. Lack of fresh fruit, vegetables, and meat left them vulnerable to scurvy, a disease Europeans did not yet fully understand.

Cartier, unwilling to reveal any weakness to the Stadaconans, hid the struggles his men were having. Twenty-five men died before the prevalence of scurvy became obvious, at which point the French were shown a locally produced infusion of cedar leaves and bark that alleviated many of scurvy’s symptoms.

However, as the winter went on, such friendly co-operation from the Stadaconans was the exception rather than the rule. At a certain point, Domagaya and Taignoagny informed their father that as much as the Stadaconans thought they were making out like bandits in their trading, the French were even more convinced that they were getting value for nothing. While in France, the brothers had picked up on the fact that the French put little value in the baubles and scrap metal they offered up. In part, this may have been Cartier’s own fault: In order to emphasize the commercial value of his discoveries to potential financial backers in France, he repeatedly downplayed the value of the goods the locals were willing to accept in exchange for fur and other valuable items.

Over the winter, the Stadaconans decided to re-appraise their bargaining position. They were encouraged to do so by the growing leverage they enjoyed over their French neighbours. In desperate need of fresh meat (and with little experience hunting local game), the French became reliant on Stadaconan hunters. Prices rose accordingly.

Relations were further strained by reports that the French had abused a young girl entrusted to their care. Meanwhile, an illness swept through Stadacona, killing at least 50 people—though it is unclear if this was blamed on the newcomers.

Although strained, the relationship between the village and the fort held together throughout the winter. As the spring of 1536 arrived, however, it was clear that something had to give.

In April, the French looked on nervously as several delegations from outlying Indigenous settlements arrived in Stadacona. Cartier feared that an attack was imminent. But this was not an assembling army. Instead, a great council was gathering to discuss the situation. Again, our knowledge of these events is mediated through the French (who did not fully understand what was going on). But we can take a stab at a reasonable scenario.

As with the other Iroquoian nations, the Stadaconan council worked through persuasion rather than coercion. Neither Donnacona, nor anyone else, had the authority to impose a decision on anyone. And the council was divided on the French issue. Donnacona led a group arguing that the French were not dealing with them in good faith, and were more of a threat than an ally. Another group, whose most vocal member was another clan headman, named Agona, argued in favour of a French alliance. Clearly there were some communication issues, and French behaviour so far had been problematic. But the potential benefits of a European alliance were too great to pass up. And if the French could not make a deal with the Stadaconans, they would likely befriend one of their rivals, like Hochelaga, or maybe the Mi’kmaq to the east.

In order to break the deadlock, Donnacona sent one of his sons to the French camp, suggesting that Cartier take Agona with him when he returned to France. As a clan leader, Agona would have great value in providing the French with knowledge and influence in the village. Donnacona’s likely goal here was to win Agona over to his side of the argument. If news got out that the French wanted to abduct/invite Agona to France, he would likely change his pro-French tune.

Cartier, however, had a totally different read on the situation. He assumed that, rather than trying to win over Agona, Donnacona was trying to remove his rival by exiling him across the Atlantic.

The misunderstanding was due to a fundamental difference between Iroquoian and European politics. Cartier assumed the Stadaconan council was an adversarial body, wherein men competed for power. And in a sense it was, but Cartier misjudged the kind of power these politicians dealt in.

Sensing that two rival factions were vying for power within Stadacona, Cartier decided to support the pro-French Agona. On May 3rd, when the ice had broken up sufficiently for a trans-Atlantic voyage, Cartier lured Donnacona and a delegation (including his two sons) onto one of the ships. Once aboard, the ships weighed anchor, whereupon Cartier “invited” the delegation to return with him to France.

The French were chased down the river by a fleet of canoes, offering generous ransoms for the return of their compatriots (a repeat of a similar scene the previous year, when Cartier had left with Donnacona’s sons). Cartier put the best face on the abduction as he could, proclaiming that Donnacona and the others were his guests and would be well treated in France. He also promised to return the following summer, and further develop the trade alliance with Stadacona.

Cartier sailed home satisfied with himself. He had killed two birds with one stone. A chieftain like Donnacona was useful to him—both to gather intelligence on the St. Lawrence, and to impress France’s royal court (and any potential backers) in anticipation of a third voyage. At the same time, Cartier assumed he had strengthened France’s position in Stadacona. Surely, following the manner of European power politics, Agona and his pro-French faction would now seize control and purge Donnacona’s allies from village government.

Cartier returned to the French port of St. Malo on July 15th, 1536. But if he’d hoped to immediately begin preparations for a third voyage, he was disappointed. King Francis was once again distracted by another round of fighting in Italy. The “Italian Wars” (or Habsburg-Valois Wars) would drag on for many more years, and draw in the Ottoman Empire (on the side of France) and Henry VIII of England (on the side of the Hapsburgs).

Cartier did his best to drum up interest in a return to Canada, but to little avail. Donnacona was perhaps even more eager than Cartier to get another voyage across the Atlantic. He studied French and regaled the royal court with tales of the unimaginable wealth that lay just beyond the rapids Cartier had seen. These were no doubt embellishments designed to tempt the greedy French. But Donnacona can perhaps be forgiven for stretching the truth in his quest to get home.

With his colonial plans put on hold, Cartier took up part-time work as a privateer, raiding the shipping of France’s enemies. It’s possible that during this period Cartier aided Irish rebels in their struggle against their English overlords.

The abducted Stadaconans did not fare well in their prolonged visit to Europe. Donnacona was treated as foreign royalty, as Cartier had somewhat exaggerated his status in an effort to promote the cause. But he died in 1539, three years into what Cartier had promised would be a 12-month visit. Of the nine others Cartier had brought to France, only the young girl whom the Stadaconans had entrusted to the French survived into the 1540s. If Cartier felt any responsibility for the deaths of his hostages, he didn’t show it.

When a pause in the Italian wars presented an opportunity to return to Canada, Cartier jumped at the chance. In October 1540, King Francis drew up a commission for Cartier to found New France, a permanent colony, and to conduct a search for the great land of wealth that Donnacona had spoken of. This was a far more ambitious project than either of Cartier’s first two voyages; and it seems that while it was still in the planning stage, Francis had second thoughts about leaving a common navigator such as Jacques Cartier in charge of it.

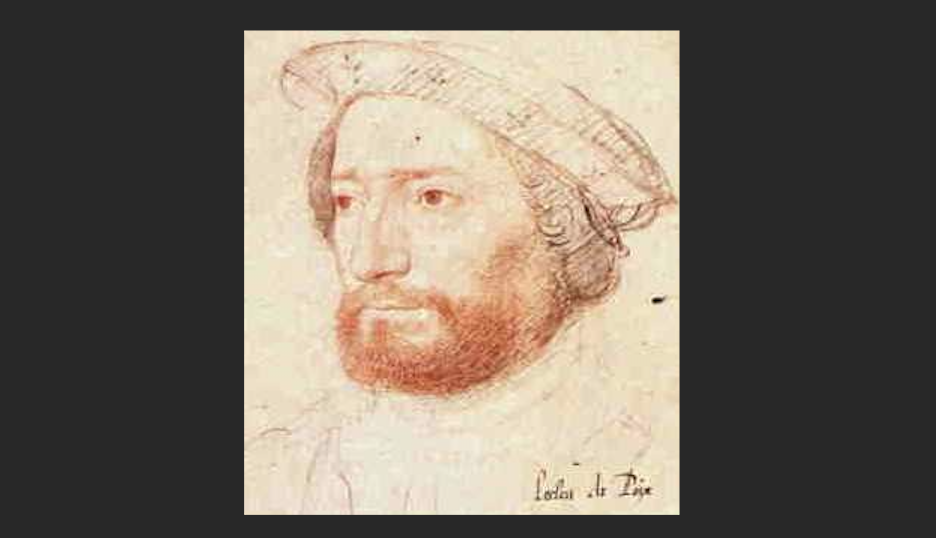

In January 1541, the King amended the commission by naming a Lieutenant-General to govern New France—a 40-year-old aristocrat named Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval. Roberval came from an old noble family based around Carcassonne, which was enough to make him a more suitable colonial commander than Cartier. It helped that Roberval was good friends with King Francis. The two had forged their friendship on the battlefield.

If those don’t sound like especially relevant qualifications for running a colony, well, they weren’t. But as we’ll see, an aristocratic bloodline and a close relationship with the King were useful traits for the viceroys of New France to have. And when those traits were absent within the colonial leadership, New France often suffered for it.

But while Roberval’s direct link to the King was an asset, he came with a host of liabilities. The first of which, his religious affiliation, was a harbinger of the problems France as a whole would face over the next century. Roberval was a Protestant, a relatively new movement then sweeping across Europe, challenging the traditional Catholic Church. While his close friendship with King Francis (who was part of the country’s Catholic majority) protected Roberval from the persecutions many of his co-religionists faced, his faith would complicate the colonial project.

This would become a familiar trend in the future of French colonial enterprise. Although France always would remain a majority Catholic nation, members of the French Protestant minority (known as the Huguenots) could be found in substantial concentrations, particularly in the south and west. More importantly, for our purposes, Huguenot preachers were particularly successful among the commercial classes, on which the financing and exploitation of inter-continental trade depended. This regional and commercial character of French Protestantism was nowhere more apparent than in the Atlantic port of La Rochelle, which was both firmly Huguenot and deeply involved in trans-Atlantic trade.

Roberval, who’d been born before Martin Luther’s rebellion against the Catholic Church, had the zeal of a convert. And he intended to apply strict rules of religious and moral conduct on his colonial subjects. This was a problem, as most of these subjects were Catholic, and so saw many of Roberval’s religious rules as heretical.

Roberval’s Protestantism also presented a diplomatic problem. The royal commission that founded New France used a lot of flowery language about spreading the “true” (i.e., Catholic) faith to the heathens. This was inserted primarily for the benefit of King Francis’s Vatican allies. The Pope (this was the era of Paul III) was allowing the French to violate the Treaty of Tordesillas, which had divided the Americas between Spain and Portugal. The least the French could do in return for granting this exception to the treaty was to expand the Vatican’s spiritual empire. By these lights, appointing a Protestant to the New France’s command was off-message.

A second liability Roberval brought to the colonial project was the rather checkered history of his personal finances. In the late 1530s, Roberval’s extravagant lifestyle had forced him into bankruptcy. And the main reason King Francis had picked Roberval to be Lieutenant-General of New France was to help his old friend get back on his feet. It had taken a royal proclamation to save him from the wrath of his creditors (and either exile or a prison cell). New France was Roberval’s last chance to prove he could get his act together.

The problem was, New France was not a profit-generating enterprise from which Roberval could simply siphon money. In fact, it wasn’t entirely clear how the colony would generate wealth. It was hoped that, eventually, a path to the Orient might be found up the St. Lawrence. But until that happened, and regular trade was flowing, it would take ingenuity and commercial acumen to make money. There was very little evidence that Roberval had either.

Not surprisingly, his Nouvelle-France project ran into financial problems before the ships even left harbour. Due to poor funding, the first batch of colonists was a motley crew. The chance for glory had attracted a few wealthy families (and even a handful of aristocrats), but most of the colony’s founders were not exactly eager, intrepid settlers: The numbers were padded out by large numbers of convicts who’d been offered the choice of continued imprisonment (in some cases even execution) or the honour of settling new lands for the King.

One of the released prisoners was 60-year-old Pierre Ronsaurd, who’d been the master of the King’s mint at Bourges until he was found altering coins. It’s likely he was recruited to assess the piles of gold that the French rather optimistically hoped would be dotting the countryside.

How feasible all this was can be judged by the reaction of the Spanish agents who were carefully observing the preparations. At first, they’d been nervous about France’s attempt to horn in on their trans-Atlantic empire. But as the details emerged, they informed their masters back in Spain that this amateurish expedition posed little threat.

The problems continued right up to the launch date in the spring of 1541. Cartier led 400 men and women on five ships across the Atlantic as scheduled in late May, but Roberval, lacking funds, remained in Europe. He intended to make up the budget shortfall the best way he knew how—through violence. Roberval spent the summer season raiding the shipping of France’s enemies, and planned on using the proceeds to re-supply the colony next summer. Until then, New France was in Cartier’s hands.

Just as in his second voyage, Cartier and his ships suffered through a rough crossing. The longer-than-expected trip created supply problems. Due to a shortage of water, the livestock the settlers had brought with them were drinking cider. Waiting for stragglers and repairs ate up a whole month in Newfoundland. The fleet reached Stadacona on August 23rd, very late in the summer, exactly three months after it had set out.

Within Stadacona, Cartier hoped that he had a powerful ally in Agona—the rival of Donnacona whom he imagined had now seized power. In this, he was disappointed. Agona was still a prominent man in the village, but Cartier had badly misunderstood Iroquoian politics. Neither Agona, nor Donnacona before him, were rulers of the village in the sense that a European would have understood. They each represented their clan segment in village councils, but had little influence outside of their kinship groups. And so Donnacona’s absence had not benefited Agona politically.

In fact, Agona, like everyone else in Stadacona, viewed Cartier’s abduction of the respected leader as a violation—especially considering that Cartier had not fulfilled his promise to return with the hostages in 12 months. In had now been five years since Cartier had left.

The Stadaconans exhibited no outward hostility, as the French remained a potential ally, and little would be gained by alienating them. But behind the official welcome was a thinly veiled sense of distrust.

It didn’t help that none of the “guests” Cartier had left with had returned with him. (As noted earlier, all of them had died, except for a young girl whom Cartier had decided to leave in France.) His decision to leave the one survivor in France had left him, once again, without a translator. But he could not risk the Stadaconans discovering that their other compatriots were dead. So instead, he claimed that the others were now great lords in France, and were happy to stay there. We have no record of what the Stadaconans thought of Cartier’s story, but it seems unlikely they believed it. (Cartier did admit that Donnacona had died, likely in a misguided attempt to strengthen Agona’s political position in the village.)

Perhaps sensing that the French weren’t particularly popular at the moment, Cartier didn’t dawdle in Stadacona. Instead, he set up his base camp 15 km upriver from the village, at Cap Rouge (which now sits within the Quebec City borough of Sainte-Foy–Sillery–Cap-Rouge).

He named the first settlement of New France “Charlesbourg-Royal,” after the King’s third son, Charles, Duc d’Orleans. The 400 residents immediately set about planting cabbages, turnip, and lettuce to test the fertility of the soil (though, starting so late in the summer, they were not expecting much of a harvest). Parties were organized to scout the area for gold, iron, and diamonds, or any other precious resources that might be nearby.

Within a few days, two of the ships were ready to head back to France, their mission as passenger liners having been completed. Cartier sent along messengers informing Roberval of Charlesbourg-Royal’s location, and some initial rock samples that looked like they contained some kind of gold-like diamonds.

After a couple of weeks, with the settlement making good progress, Cartier decided to turn his attention to what he considered his primary mission—further exploration of the St. Lawrence. It was already mid-September, so a large-scale expedition before winter was not possible. But Cartier wanted to get a closer look at the rapids he had seen on his visit to Hochelaga six years previously.

Cartier and a small group of men sailed upriver and landed on Hochelaga’s island. This time, they did not immediately encounter any locals. Leaving a few men to guard their beached boats, Cartier and some others pressed westwards to get a closer look at the rapids. The Lachine Rapids were as wild as the Hochelagans had claimed. Further progress upriver was not really possible with the European watercraft Cartier had at his disposal. And a fuller exploration would have to wait until next year, when Cartier could organize an expedition (and perhaps enlist support from the Hochelagans).

Speaking of the locals, Cartier was surprised to find about 400 of them gathered around his boats when he returned. Fortunately, he had not abducted any of their friends last time he was there, and so the French received a warm welcome. For now, curiosity, and the potential for trade, were more than enough to ensure good relations. Even so, Cartier was outnumbered and far from his base camp. He reverted to his default wariness, and pushed off downriver the second the ritual exchange of gifts had been completed.

Cartier came back discouraged, but still confident that he was close to a westward passage. That confidence was dealt a severe blow, however, when he returned to Charlesbourg-Royal.

In his absence, relations with the Stadaconans had gone from respectfully chilly, to downright hostile. It was clear by this point that the abductions of five years ago were just that—abductions. Cartier’s hope that Agona would be some kind of grateful beneficiary of Donnacona’s demise had proven hopelessly ignorant. The abduction merely unified the Stadaconans in their distrust of the French (and Cartier in particular).

The behaviour of the French since their 1541 arrival had done little to improve Stadaconan opinions. The wood fort Cartier’s men had constructed was a provocative violation of Stadaconan territory—as was Cartier’s voyage upriver to Hochelaga. The key to any potential alliance between Stadacona and the French was recognition of the village’s status as a broker between the Europeans and the Iroquoian peoples in the interior. Cartier had undermined such an arrangement by ignoring any privileged status Stadacona might have in dealing with other villages.

At first, during the fall, the French were content to ignore the increasingly frosty attitude of their neighbours. But as winter set in, Cartier was reminded of how much he had relied on Stadaconan aid back in the winter of 1535–1536. This time, the Stadaconans refused to trade any of the food they had stockpiled for the winter, no matter what the French offered in return. Then, at the height of the winter, the Stadaconans turned outright hostile. Attacking the French fort was out of the question, but a kind of guerrilla war set in. French hunting parties and gangs of wood cutters would sometimes leave and never come back. In all, 35 Frenchmen were killed over the course of the winter, and more suffered from hunger and disease within the palisades of the isolated community.

The experience was a turning point for the otherwise optimistic Cartier. Had all the tales of the great seas and fabulous riches in the west been a lie? As Cartier hunkered down in the cold, he was not in the mood to trust the word of a Stadaconan. Cartier and his fellow Frenchmen decided that the second the ice cleared out of the St. Lawrence, they would abandon the colony and head home.

Cartier’s only hope lay in the possibility that the glittering diamond minerals they’d found in the area turned out to be actual diamonds. He’d already sent back some initial samples for evaluation in France. And now his men had gathered more, filling their cargo holds with the stuff.

In June 1542, Cartier set sail, hoping that a large haul of diamonds would distract everyone from the failure of the colonial project.

After a few days’ travel, the former settlers were anchored at a natural Newfoundland harbour near the modern-day city of St. John’s, a well-known meeting point that Europeans had been using for Atlantic crossings for decades. Just as they were about to push out into the open sea, they caught site of their Lieutenant-General coming the other way. Roberval’s money-raising piracy campaign had been successful, and he was bringing a fresh group of settlers and provisions to strengthen Charlesbourg-Royal.

The veteran soldier was not happy to hear that, at the first sign of hardship, the initial wave of colonists had run for safety. However, Roberval was perhaps not surprised. What else could you expect when you put a common Breton pilot in charge of a colony?

Roberval informed Cartier that he still had a job to do. Their combined fleet would head upriver and re-build the settlement, whether the locals liked it or not. Had they not been commissioned by the King himself?

Cartier smiled and nodded. Roberval was his superior, after all. But at the first chance he got, he slipped away in the dead of night, and sailed for France. Cartier had already gambled on the diamonds saving his career. Disobeying a direct order from Roberval didn’t really change the calculus much.

As it happened, Cartier’s gamble blew up in his face. Upon arriving home, he discovered that the diamonds he had banked so much on were worthless pyrite, also known (appropriately enough) as fool’s gold. Rather than being hailed as a new Columbus, Cartier’s lasting legacy in French culture was the phrase “as false as Canadian diamonds.”

He was not ruined exactly, but Cartier’s career as an explorer and budding colonial administrator was over. Cartier returned to St. Malo, where he died about 10 years later, at the age of 65.

Cartier’s dream lived on, however, despite his exit from the scene. Roberval was determined to complete his mission, undeterred by the fears that had driven Cartier and the other settlers to so dishonourably abandon their posts.

But, before heading up the St. Lawrence, Roberval’s fleet played host to an odd little episode that’s worth a diversion.

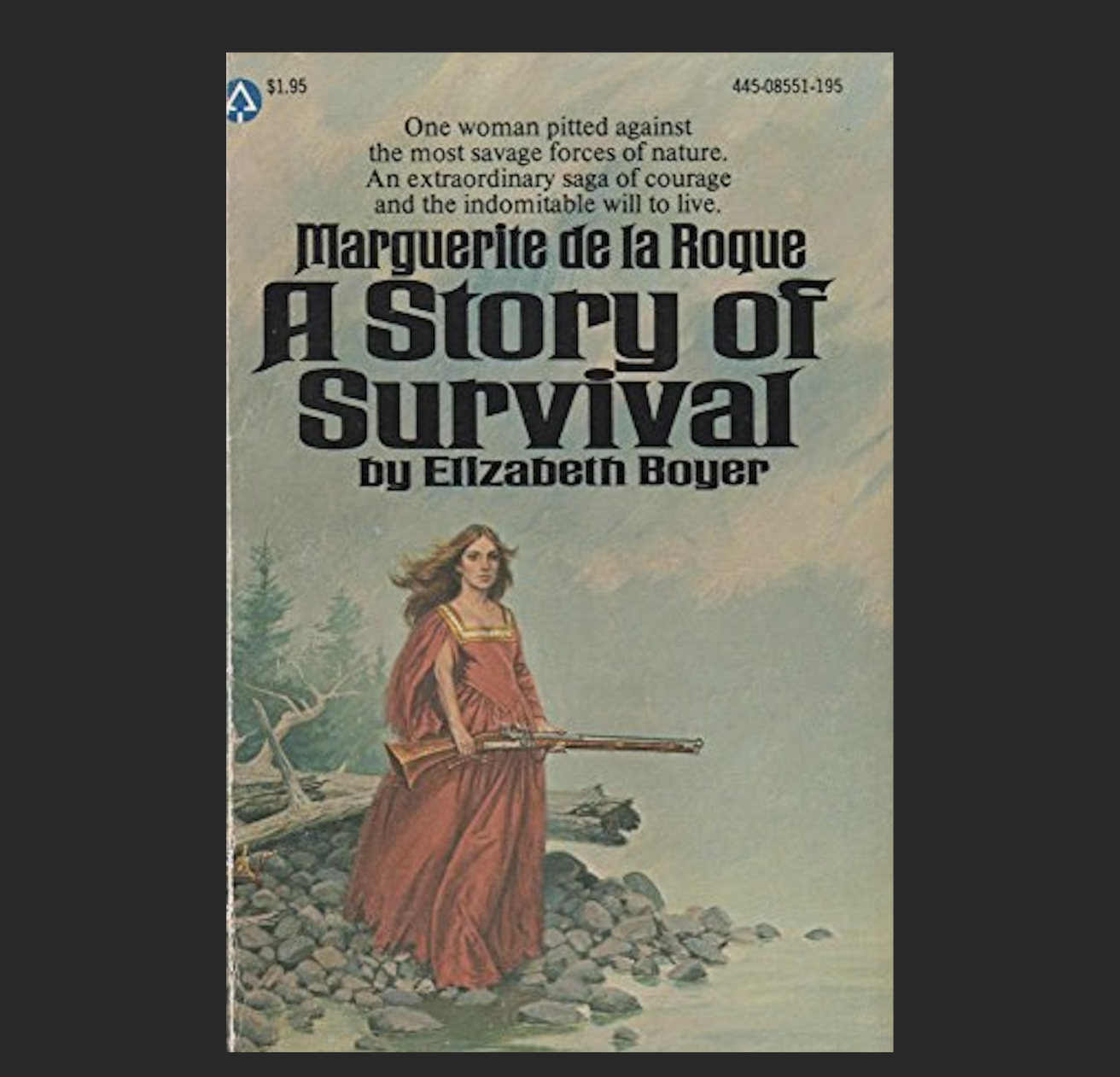

As mentioned earlier, the colonists of New France were an eclectic mix of social classes and (in the interests of future growth) males and females. One of the passengers was Roberval’s niece (or possibly cousin), Marguerite de la Roche. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, Roberval marooned Marguerite (along with her maid) on an island just off the coast of modern Quebec, on the northern shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Historians still debate which island this was—possibly Harrington Island, or the aptly named Île de la Demoiselle.

It’s possible that Roberval (who had uncompromising Protestant morals) was punishing Marguerite for taking one of the male colonists as a lover. In fact, the young man in question also ended up on the island (though it’s not certain whether he was exiled, too, or snuck off his ship to follow Marguerite).

But while Roberval did have a well deserved reputation as a stuffy puritan, it’s possible he had a more prosaic motive. Roberval and Marguerite were co-owners of significant properties back in France. With her out of the picture, Roberval may have been more free to use the properties to address his endless financial problems.

Whatever Roberval’s reasons, the trio of marooned souls (Marguerite, her maid, and her lover) lived out what one historian has called “one of the saddest love stories never to become a major motion picture.” The group survived the rest of the summer well enough, gathering berries and catching small game. Marguerite even became pregnant, and gave birth to the first European child born in Canada since the Norse period.

But the winter was harsh, and claimed the lives of the man, the maid, and the baby. By the following summer, only Marguerite still lived. She was eventually rescued by European fishermen, after about 16 months on the island.

If that little story has inspired you to root against Roberval, I’ve got good news: His attempt to re-establish a colony on the St. Lawrence did not go well.

Roberval wasn’t particularly popular among the colonists. Considering how he dealt with his own kin, it isn’t hard to imagine why. In addition to being a Protestant among (mostly) Catholics, he was also a strict disciplinarian, a product of his army days. This was not necessarily a bad quality in a colonial governor, but many of his subjects were either elites (unused to military discipline) or criminals taken from France’s prisons (who were a bit too used to harsh discipline). Liberal use of punishments such as whipping, withholding of food, banishment to the wilderness, and even hanging, did not win Roberval the love of the colonists.

But despite all that, things didn’t start out too badly.

The Charlesbourg-Royal site had been dismantled. Whether this had been done by Cartier just before he left, or by the Stadaconans just after, is unclear. In any case, Roberval immediately began work on a new settlement. Applying his background in military engineering, Roberval built an even more impressive complex. He also did Cartier one better by naming the settlement, not after the King’s son, but after the King himself: France-Roy.

Relations with the Stadaconans seemed to improve, too. Perhaps they were intimidated by Roberval’s superior fortifications. Or perhaps their resentment had been directed toward Cartier himself, rather than the French as a whole. In the future, the individual personality and the character of European colonial leaders would play an important role in Indigenous diplomatic relations.

But even in the absence of local resistance, France-Roy struggled through the harsh Canadian winter. Those who didn’t work were not fed, which turned into a famine-in-the-making when many became too ill to work. The Lieutenant-General was eventually forced to soften his stance, and provided half-rations to those too sick to work.

Still, France-Roy witnessed the largest incidence of scurvy in any of the early French settlements. By the spring, 50 of the 150 colonists had died of the disease, more than had been killed by hostile Stadaconans the previous winter.

Despite this indication that Cartier may have been right to abandon the project, Roberval decided to stay and explore the St. Lawrence himself. His instincts still told him that Cartier had given up on the passage too easily.

In the spring of 1543, Roberval went upriver with a large party of 70 men spread out over eight boats. He managed to trade with the Hochelagans, acquiring a large supply of corn, which would hopefully make the next winter more bearable. But Roberval found the rapids just as impassable as Cartier had. One of the boats capsized in an ill-advised attempt to run the dangerous waters, with the loss of all its crew.

Thoroughly discouraged, Roberval returned to France-Roy in a sour mood. When supply ships arrived from France that summer, he joined them for the return voyage. Thirty settlers were left behind to struggle through another winter, but the writing was on the wall: New France was simply not feasible as a permanent colony. By the following year, the project was totally abandoned.

Back in France, a royal commission investigated the conduct of both Cartier and Roberval. The verdict was that while neither man had covered himself in glory, the fault lay with Canada itself, not the colonial leadership. The winters were too cold; the upper St. Lawrence was impenetrable; and the local commodities had no commercial value.

The presence of relatively sizable villages at Stadacona and Hochelaga also posed a problem. Like the Norse 500 years earlier, the French balked at the manpower that would be required to settle already inhabited lands. Unless the French state was willing to commit significant resources to colonization, French settlers would always be at the mercy of local populations.

As a result, the French colonial project was shelved for the foreseeable future. It would take another 50 years for circumstances on the St. Lawrence to became favourable for French settlement.