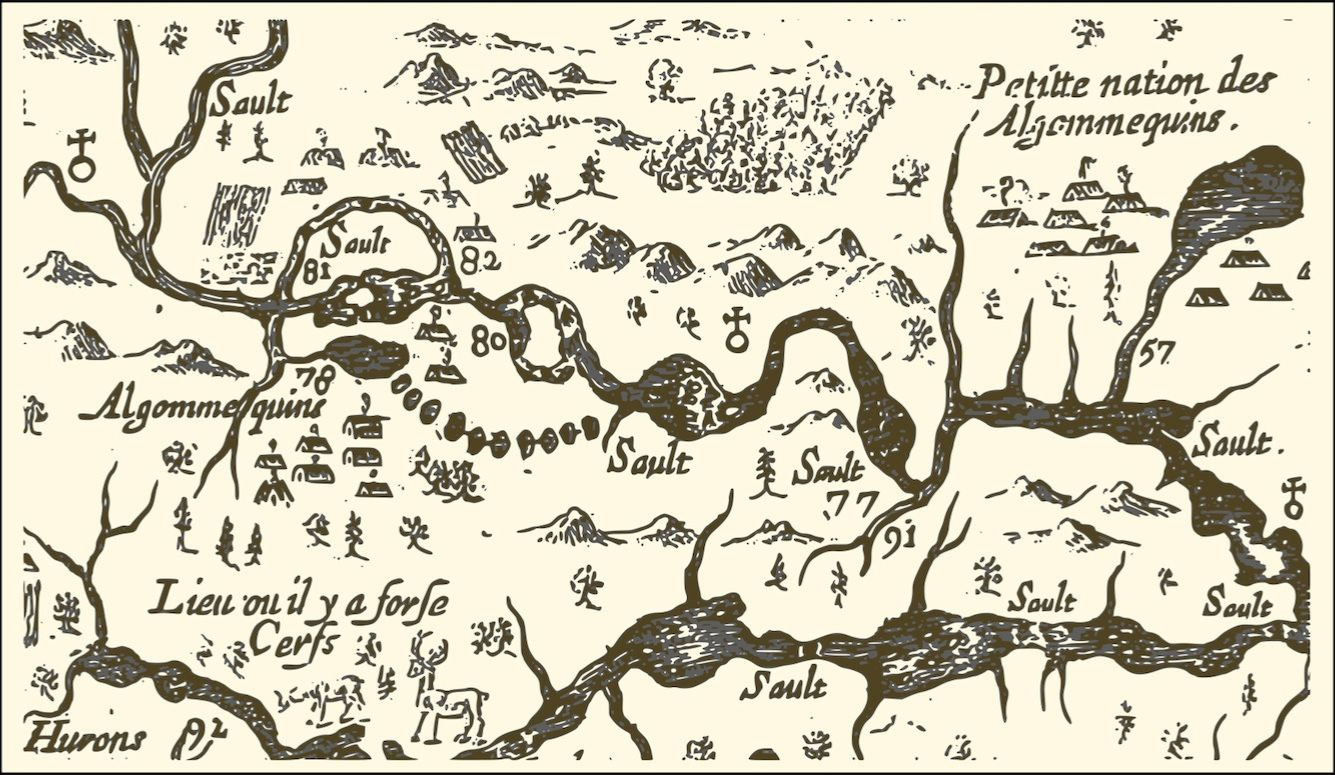

Nations of Canada

The Laurentian Coalition Takes Root

In the 16th instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ historian Greg Koabel describes how Samuel de Champlain overcame a decade of frustration by finally establishing a successful French fur-trading monopoly.

· 25 min read

Keep reading

Natalism and the Welfare Mother

Stephen Eide

· 6 min read

A New Middle East?

Brian Stewart

· 6 min read

Greta Thunberg’s Fifteen Minutes

Allan Stratton

· 10 min read

Gentrifying the Intifada

John Aziz

· 8 min read

Creative Writing in the Age of Trump

Daphne Merkin

· 7 min read