Editorial

Cancel Culture Comes for Woody Allen (Again)

It’s no use demanding ethics, logic or accountability from a mob because the mob has no identity or legal status.

In 2003, a 19-year-old worker at a Colorado resort accused NBA basketball star Kobe Bryant of raping her in his hotel room. Bryant’s endorsement deals were canceled, and it looked like this might be the end of his career. But prosecutors dropped the case when the alleged victim decided not to testify. Bryant, who admitted that he had engaged in adulterous sex with his accuser, argued that the liaison had been consensual, apologized publicly, and settled a subsequent civil suit on undisclosed terms. By the time Bryant died in a helicopter crash earlier this year, his public image had been restored, and Bryant received the NBA’s equivalent of a state funeral. When Washington Post writer Felicia Sonmez tweeted out a reference to the sexual-assault allegation amidst the grieving, she was suspended from work, and chastised by the Post’s executive editor, who told her, “A real lack of judgment to tweet this. Please stop. You’re hurting this institution.”

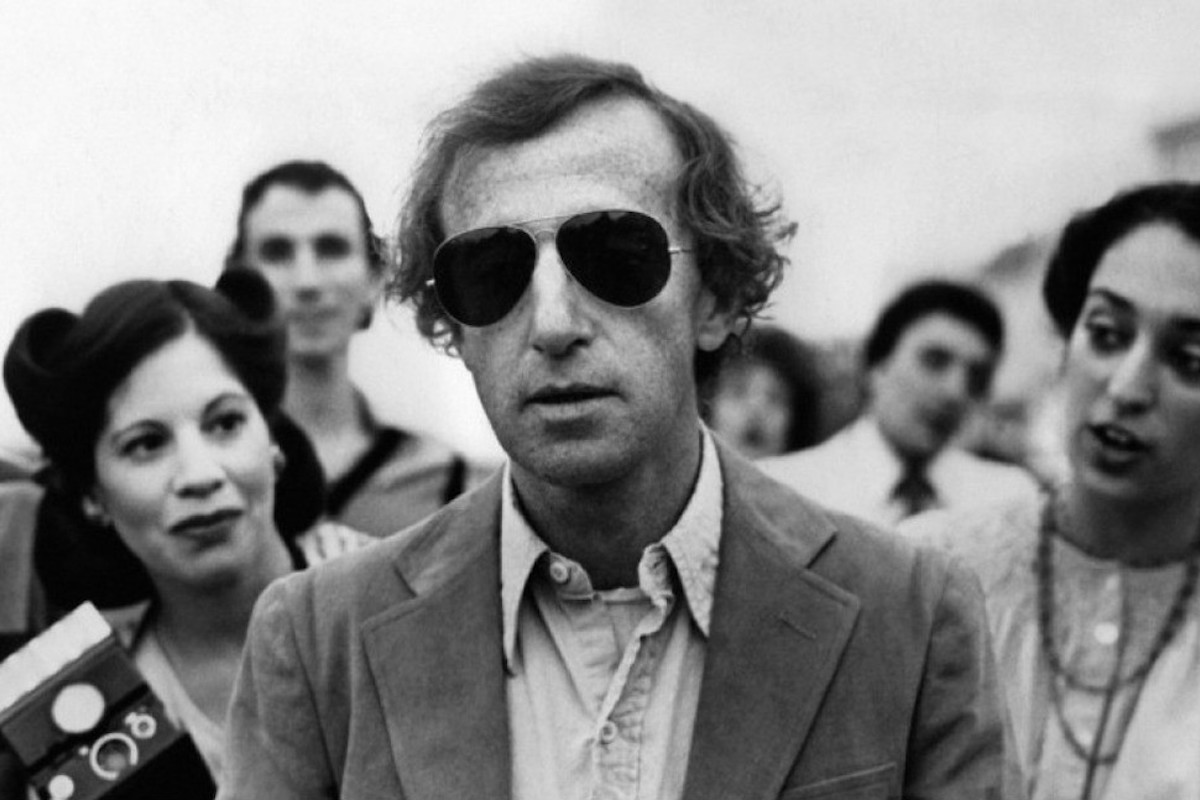

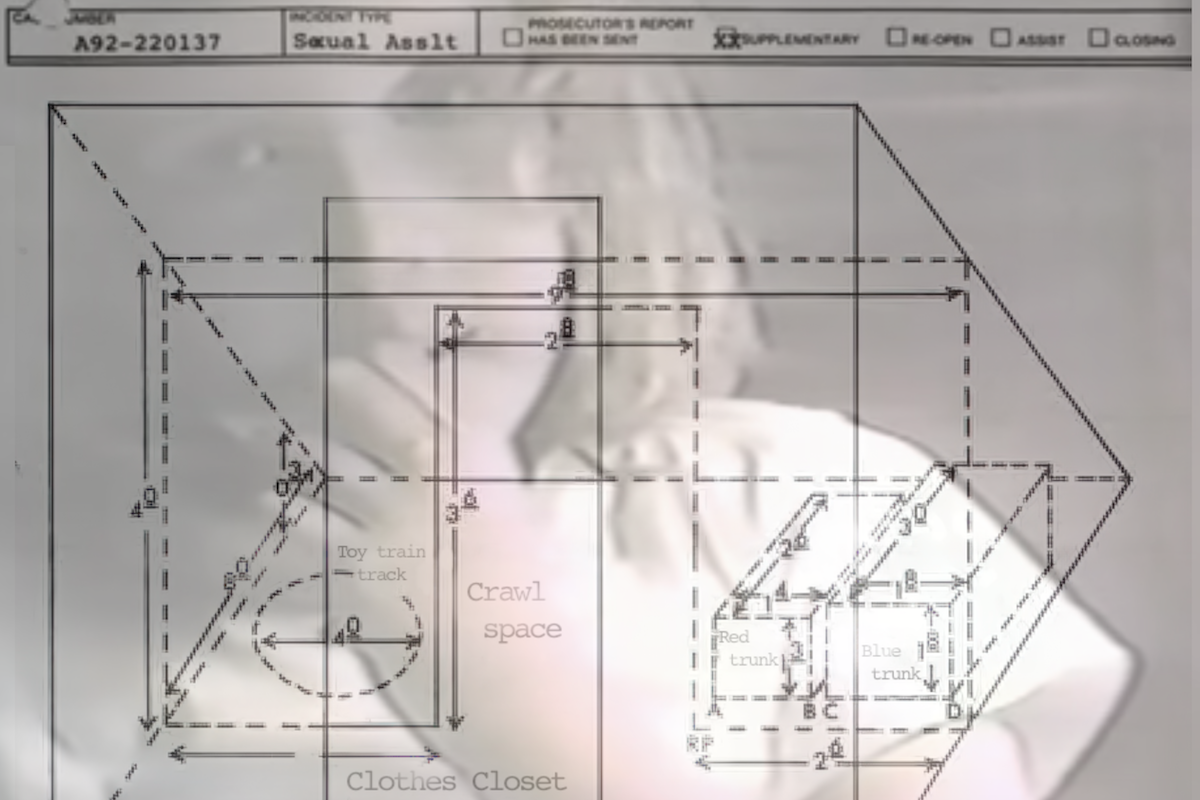

In the summer of 1992, actress Mia Farrow found out that her adopted daughter Soon-Yi was still romantically involved with Mia’s ex-long-time-boyfriend and collaborator, Woody Allen. According to then-21-year-old Soon-Yi, Mia responded by telling a psychologist that Woody was “satanic and evil,” and that she needed to “find a way to stop him.” Three days later, seven-year-old Dylan Farrow, Mia’s daughter, accused Allen of molesting her in Mia’s Connecticut house. But when the child’s accusations, which were captured on videotape with reported coaching from Mia, were investigated by the Connecticut State Attorney, the Child Sexual Abuse Clinic of Yale-New Haven Hospital and the New York Department of Social Services, no credible evidence could be found to support the allegations. As Kyle Smith reported in a definitive National Review article, Mia’s own nanny “quit the family rather than support Mia’s version of events.” And Dylan’s brother Moses wrote in 2018 that the Mia-Dylan abuse narrative simply made no sense given the architecture of the Connecticut house where the abuse allegedly took place. Yet Woody Allen was nonetheless smeared as a rapist and pedophile. And last week, his publisher, Hachette Book Group, announced it would cancel its deal to publish Allen’s memoirs.

It’s no use demanding ethics, logic or accountability from a mob because the mob has no identity or legal status. But as the cases of Kobe Bryant and Woody Allen show, the distinguishing problem with modern cancel culture isn’t just mobs per se: It’s the gatekeepers who surrender to the mob’s Manichean judgments, often under the guise of social justice, thereby encouraging more mobs in the future. As Stephen King put it, even Allen’s critics should be concerned: “It’s who gets muzzled next that worries me…Once you start, the next one is always easier.”

A fair assessment of Kobe Bryant is that he was one of the greatest players in the history of basketball, as well as someone who may or may not have sexually assaulted a woman in 2003. A fair assessment of Woody Allen is that he is a great and influential film director who also tore apart his extended family by entering into a very odd (but not illegal) sexual relationship with his ex-girlfriend’s adopted 21-year-old daughter. It would be perfectly normal for the same fans who turned their backs on Bryant in 2003 to eventually forgive him, and then cheer him on when he led the Los Angeles Lakers to championships in 2009 and 2010—just as it would be perfectly normal for the same cineastes who lavish praise on Woody Allen’s oeuvre to remain unsettled by the origins of his marriage to Soon-Yi Previn, while also recognizing that the Mia-Dylan abuse allegations are nonsense.

Which is to say that, morally speaking, most of us can walk and chew gum. We recognize that everyone is flawed and complicated, and that forgiveness is possible. True, such attitudes are anathema to the mob mentality. But most ordinary people aren’t part of mobs. It’s only on Twitter, a medium that self-selects for hair-trigger puritanism and moral hypocrisy, that mobs get to form a majority government. The problem comes when the firewall between the fake world of Twitter and the real world of human institutions breaks down, and social-media star-chamber verdicts are ratified by institutional gatekeepers.

Absolutists should be allowed to shriek at each other all they want on social media. That’s what it’s for. But they shouldn’t get to dictate workplace policy at the Washington Post. Nor should they have up or down veto power over whose publishing contract gets honoured by the Hachette Book Group. In both cases, Bryant and Allen, corner-office publishing executives followed the mob demand that only one view is permissible: Bryant good. Allen bad. And in both cases, they tried to mask cowardice as virtue. Post management tried to gaslight Sonmez, accusing her of “a real lack of judgment,” and of “hurting this institution.” And Hachette justified its decision to drop Allen by recourse to the need to offer “a stimulating, supportive and open work environment for all our staff.”

Hachette’s decision followed on a group of its own employees staging a “walkout” to protest the publication of Allen’s book. A similar movement is underway at the Guardian newspaper, where several hundred employees are accusing the management of “transphobia” in light of a Suzanne Moore column arguing the fairly obvious fact that “Sex is not a feeling. Female is a biological classification that applies to all living species. If you produce large immobile gametes, you are female. Even if you are a frog. This is not complicated, nor is there a spectrum.”

It once was the case that powerful media entities such as the Washington Post, Hachette, and the Guardian were insulated from mob pressures, since their own employees naturally would close ranks in times of crisis. But thanks to social media, many office workers now spend vastly more time interacting with people outside of their workplaces than within those workplaces, a phenomenon that has caused a reorganization of professional loyalties. Writers, artists, and activists, in particular, often seem more preoccupied with the opinions of people they have never met than with long-time co-workers who sit in the next cubicle. Niche creative sectors such as young adult fiction, poetry, comedy, Canadian literature, and even knitting all present case studies wherein small, densely interconnected social-media ecosystems allow cliques of highly motivated ideologues to police speech, prosecute grievances, and punish heretics.

But perhaps nowhere is the phenomenon more pronounced than in academia, where the inherently conservative (and sometimes even puritanical) machinery of elite professional gatekeeping can be co-opted by a campus’s most implacably progressive constituencies—with the result that professors and students are afflicted by the worst of both ideological worlds. A particularly piteous example is former professor Bo Winegard, recently fired from a tenure-track job at Marietta College in Ohio, apparently because of misinformation and ad hominem attacks posted by trolls on a site called RationalWiki. One troll actually emailed Winegard after his firing to brag, “I win.”

It’s a sad and petty person who regards another man’s misfortune as a “win.” But this spirit of vicious schadenfreude always lies close to the surface in every campaign of this kind. If these people can take down the director of Annie Hall, Husbands and Wives, and Vicky Cristina Barcelona, they can take down any one of us.