Art and Culture

Startling Intimations of Greatness

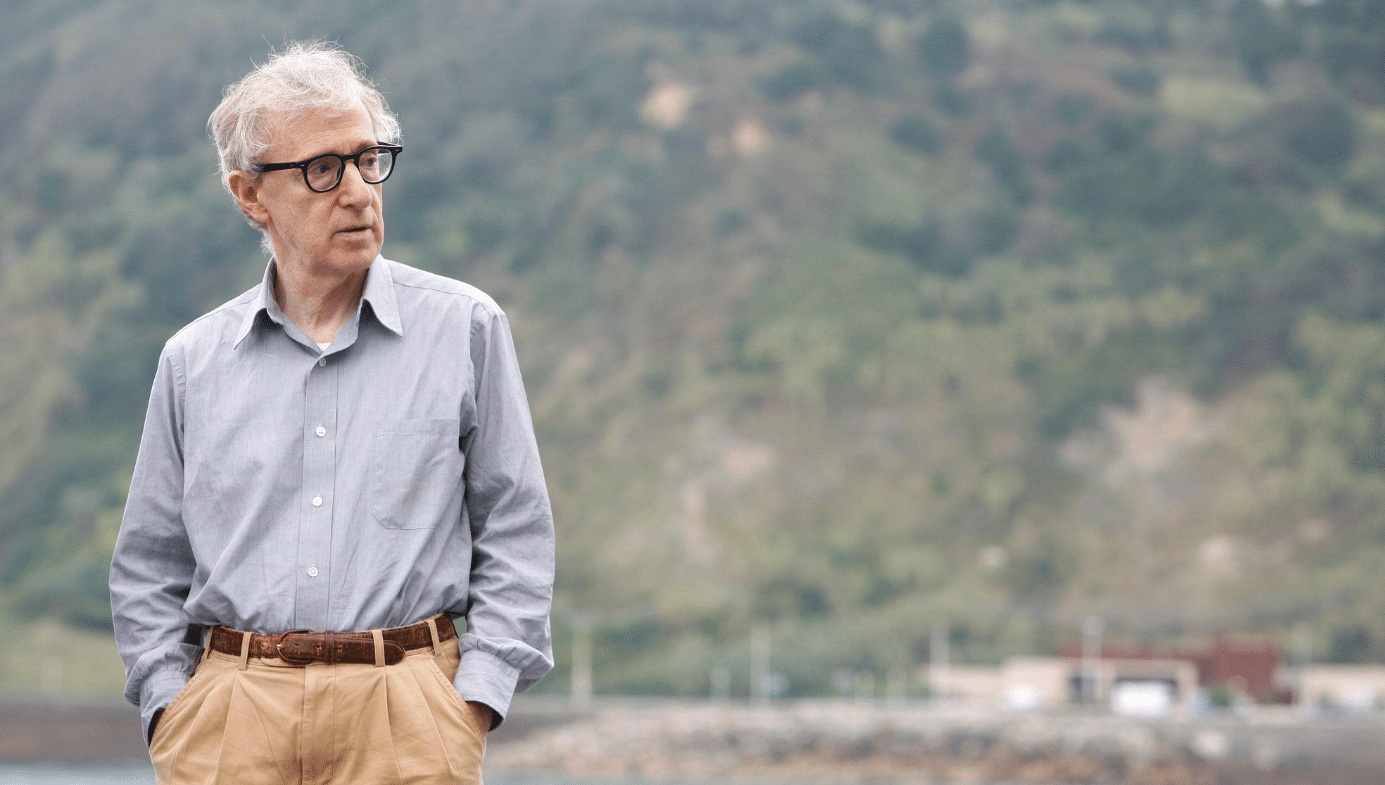

As we await the release of Woody Allen’s 50th feature film, his biographer looks back on the career of one of America’s great cinematic artists.

I.

On September 18th, Woody Allen surprised the world by casually suggesting that he might retire from film-making. “My idea, in principle,” he told Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia, “is not to make movies anymore and focus on writing these stories and, well, now I’m thinking more of a novel.” This apparently unambiguous remark was contradicted the following day by a hasty statement from one of Allen’s representatives: “Woody Allen never said he was retiring, nor did he say he was writing another novel. He said he was thinking about not making films as making films that go straight or very quickly to streaming platforms is not so enjoyable for him, as he is a great lover of the cinema experience. Currently, he has no intention of retiring and is very excited to be in Paris shooting his new movie, which will be the 50th.”

Shortly before the announcement, Allen had given an interview to Alec Baldwin on Instagram live and spoken about how the joy had gone out of the movie scene following the advent of streaming and the damage inflicted on the industry by the pandemic. Allen’s grandfather owned a major movie house in Brooklyn and that gave him a taste for the romance of the movie theater at an early age. Ambiguity about Allen’s future remains, but his 50th film is a milestone that merits a retrospective assessment, even so. I find it unlikely that he will give up directing entirely—his creative fecundity has already defied the odds of how long a filmmaker can continue to produce exceptional work. Despite some threadbare films in recent years, Allen continues to score the occasional hit, including Midnight in Paris, the Oscar-winning Blue Jasmine, and the charming trifle, A Rainy Day in New York.

I have been rewatching many of Allen’s films—films I’d seen at least five times each while writing his biography in 2015—and they don’t date; they remain as fresh, vital, moving, and funny as ever. I wouldn’t go as far as his manager, Jack Rollins, who said to me shortly before he died, “Woody is one of the seven wonders of the world,” but I can understand why Rollins devoted so much of his life to Allen’s career. Allen’s opinion of himself, on the other hand, serves as a reminder that artists are seldom the best judges of their own work. He once remarked that, as a comedy writer, he “sat at the kiddie’s table” and could never measure up to the great dramatic artists. On this point, he was clearly mistaken. Over the course of a prolific life’s work, Allen has indelibly captured the tragedy and joy of the human carnival in extraordinarily original ways.

Admittedly, the quality of Allen’s output has been maddeningly uneven. Early on, he developed a habit of following a terrific film with a middling or weak one. He seems to need to fail in order to succeed. “People always ask, do you think you’ll wake up one morning and not be funny or have writer’s block?” he told Stuart Husband of the Telegraph. “But that wouldn’t occur to me. It’s not a possibility to me.” Failure wouldn’t last: “You throw enough stuff against the wall, something’s eventually gotta stick, right?” By my count, the upshot has been 25 excellent films out of 49—a staggering achievement. He has written and directed almost all of these himself (a handful were co-written), and in spite of the misfires, he remains one of the five greatest American filmmakers, alongside Orson Welles, Francis Ford Coppola, John Ford, and Martin Scorsese.

Allen’s relationship with his audience is a very personal one because he starred in almost all his early films and because they often appeared to be autobiographical. His back-catalogue contains enormous variety and emotional breadth, which has allowed us to see so many sides of him. And as an auteur working with a highly unusual degree of creative control, he has always been free to make the film he feels like making (even if he later declares himself disappointed by the results). Studio executives are shown nothing and never permitted to visit the sets and Allen makes no concessions to taste, popularity, or anything else. Very few directors have been permitted that kind of artistic liberty. The studios put up with it all because his films have usually been cheap to produce, and because they realised that he was a valuable cultural commodity. Allen has even managed to remain indifferent to his critical reputation and box office returns, so long as they didn’t prevent him from making his next movie.

From the outset, Allen had a strong intuitive sense of how to make deceptively simple films layered with dramatic complexity. His films don’t employ casts of thousands, complicated visual and sound effects, or vast sets; they are usually short and intimate character-driven comic dramas shot on location (although those locations can be dazzling). Audiences went to see an Allen film not to immerse themselves in spectacle, but simply to hear what he had to say. If the fervor that attended Allen’s early work has abated in recent years, it’s probably because the later films (with the notable exception of Midnight in Paris) remind us too much of his classics. After 49 films, he doesn’t seem to have many unexpressed thoughts left.

II.

Woody Allen began his writing career in the Broadway milieu of most Jewish comedians, but on a somewhat more intellectual level. He got his start at the Tamiment resort, a more highbrow version of the Catskills, situated in Shroudsburg, Pennsylvania. Danny Kaye, Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, Carl Reiner, and Mel Brooks had all performed there, and it served as a training ground for writers. Neil Simon and his brother Danny wrote sketches for its weekly Saturday night shows.

Allen’s experience at Tamiment moved him from joke-writing into sketch-writing, directing, and acting, and although stand-up comedy petrified him at first, he soon became an accomplished performer. Carol Joffe, a costume designer on Allen’s films, recalled for me his early stand-up at the Bitter End club in Greenwich Village. “I saw Woody at the very beginning get up on stage and utter his first trembling words. He was a nervous wreck but he was brilliant. Woody was really terrified of going places alone, entering rooms full of people. He was very frightened of people even though he was very sure of himself in certain ways.”

At the time, a plethora of talented Jewish comedians appeared on Johnny Carson and the Ed Sullivan Show (some of whom are included in the opening to Broadway Danny Rose). Allen went on to transcend them all: Billy Crystal, Lenny Bruce, Joan Rivers, Shelley Berman, Mort Sahl, Elaine May, Dick Cavett, and Carl Reiner. As a writer, he left Neil Simon’s stereotypes in the dust. He was a different kind of stand-up comic to his predecessors, Milton Berle, Jack Benny, and Bob Hope. He didn’t try to appear superior to his audience. On the contrary, he used his self-deprecating wit to reassure them that he wasn’t as good as they were, and the jokes were at his own expense, not at the expense of an absent wife or mother-in-law.

Allen gave the impression that he was betraying something a little more personal and autobiographical than expected. “We’ll go over recent happenings in my life,” he would say. “Then we’ll have a question and answer period.” He seemed to be suffering a lot. Short, balding, and bespectacled, he was not a snappy dresser. He resembled the stagehands more than the main event. And he didn’t seem to care what you thought of him as he chattily recounted his worst flaws, and confessed all the childish and cowardly things he’d done. He also capsized the expected male-female dynamic—in his stories and routines, he would always be the weak, needy one.

When he moved from stand-up to movies, Allen maintained the same posture. Notwithstanding its derivations from Chaplin, Keaton, and Laurel and Hardy, the Allen persona was an innovation—a vulnerable, inadequate, insecure, and often helpless man who cringes when called upon to kill a spider or drop a lobster into a pot of boiling water. His attempts at machismo were invariably played for laughs and he is often pathetically dependent on his lover, begging her not to leave him at the end of Manhattan even though he has manipulated her into doing so.

This was all a startling change from what Hollywood had traditionally understood to be leading man material. In his early films, he might appear to be something of a loser, but Allen was careful to avoid that trap, too. He understood the flaws of those who considered themselves his betters, and in the end, he usually got the girl (who was usually Diane Keaton), as if his painful self-awareness was what made him more attractive and successful in the long run. Of course, this self-effacing act is not to be confused with the real thing. Allen always knew what he was doing. But the character he created worked to his advantage and made him an immensely popular comic.

His Jewishness was also a striking component of his success. He was working in a world in which other Jews had been major stars (John Garfield, Edward G. Robinson, Paul Muni), but they weren’t thought of as Jews by audiences. Nor did they usually play Jewish roles (they often played Italians for some reason). But everyone knew that Woody Allen was a Jew. It was one of the most important things about him, and he was funny about it. He was nebbish and flaunted his stereotypically Jewish characteristics: he couldn’t put anything together and made intellectual jokes. “You make the joke first so that they can’t,” comedienne Marilyn Michaels once remarked. “Humor undercuts the whole thing, the hatred. So the fact that Woody does that, it’s like saying, I know what I am. You can’t make fun of me. I’m doing it first. You put yourself in peyes [sidelocks], as Woody did, turning into a Hasid in Take the Money and Run and Annie Hall so they won’t.”

His asides about antisemitism and the nightmare of Nazism and the Holocaust began in early films like Annie Hall and probably find their clearest expression in his greatest work, Crimes and Misdemeanors. “The crimes of the Nazis were so enormous,” he once wrote, “it would be justified if the entire human race were to vanish as a penalty.” He later repeated those words in one of his most personal films, Anything Else. Elie Wiesel, Allen once noted, “made the point several times that the inmates of the camps didn’t think of revenge. I find it odd that I, who was a small boy during World War II and who lived in America, unmindful of any of the horrors the Nazis’ victims were undergoing, and who never missed a good meal with meat and a warm bed to sleep in at night, and whose memories of those years are only blissful and full of good times and good music—that I think of nothing but revenge.”

Preoccupations like these did not, however, diminish his appreciation of the ironic and the absurd. “Funny is money,” he once said, and by the age of 20, he was already making more in a week than his parents made in a year. That initial financial security lifted him onto a perch from which he could study the human condition at his leisure. He knew how fortunate he had been. “I’ve lived out all these childhood dreams,” he told Robert Weide. “I wanted to be a movie actor. I became one. I wanted to be a movie director and comedian. I became one. I wanted to play jazz in New Orleans and I played in street parades and joints in New Orleans and played opera houses and concerts all over the world. There was nothing in my life that I aspired toward that hasn’t come through for me.” Then he added with gentle, self-mocking irony: “But despite all these lucky breaks, why do I feel I got screwed somehow?”

Allen has always lived well. He loves the upper East Side of Manhattan with its proximity to Central Park. I once asked Allen’s boyhood friend, Jerry Epstein, a psychiatrist, why Allen liked wealthy neighborhoods so much. “It’s a hedge against death,” he replied. But Allen was never a victim. Very early, he set about defining and working for his goals. He had very little in common with the characters he portrayed in his films. If he shared their insecurities and fears, he never acted them out. He was not a bumbler. He was not ingratiating. He made no attempt to be affable with strangers. His boyhood friends all told me that he led the pack: he was the fastest runner, a good basketball player (in spite of his diminutive stature), a clever magician, and a card player who aced out the competition.

“I remember when I first saw Woody on the street,” Norman Podhoretz told me. “I was struck by how utterly different his posture was from his image: strong, stiff, upright. The schlemiel he plays is a persona. He does it well. It clearly isn’t him.” Elsewhere, theater critic John Lahr wrote: “There’s a difference between the magician and his bag of tricks. Allen does not stammer. He is not uncertain of what he thinks. He is courteous but not biddable. He is a serious, somewhat morose person who rarely raises his voice, who listens carefully and who, far from being a sad sack, runs his career and his business with admirable, single-minded efficiency.” Diane Keaton describes him as having “balls of steel.”

III.

When I began working on my book, I knocked on Allen’s door to introduce myself as his unauthorized biographer. Standoffish at first and dismissive whenever I praised one of his films, he finally relaxed as he “got used to” me (as he had indicated he would), and responded to my questions with kindness, directness, and care. He is smart in the way that the instinctive artist, not the intellectual, is smart. He is an ardent devotee of Ingmar Bergman with a gift for jokes and wisecracks. His conversation veers from movies to craft to friends like Billy Crystal and Marshall Brickman (author of The Jersey Boys and co-writer of four of Allen’s best films). He seems to be more excited by Groucho Marx than by Friedrich Nietzsche or Fyodor Dostoevsky. At night, he watches basketball and baseball on TV.

Allen’s work ethic was ingrained from an early age, and he believes it shaped his life. “I knew this when I was in my late teens,” he told Stig Björkman in 2000. “That there were always going to be distractions as well. And I felt that anything that distracted from the work and minimized your effort on it was a self-deception that was going to be detrimental. So to avoid getting caught up with a lot of writing rituals and time-wasting, you’ve got to get there and just work. Art in general, and show business, is full to the brim of people who talk, talk, talk. And when you hear them talk, theoretically they’re brilliant and they’re right and this and that, but in the end it’s just a question of ‘Who can sit down and do it?’ That’s what counts. All the rest doesn’t mean a thing.”

From that ethic emerged a pattern of writing to which Allen has adhered throughout his working life. The hardest part of writing for him is the “pre-work”—finding the ideas and his conception of the entire story. After that, he is home free. “I can celebrate. Because that’s the day when everything is over.” All the agonizing work has been done. Writing the rest is “pure pleasure.” The creative process “is culmination, it is flying, it is being wholly alive,” he told Björkman. “I start to think. I walk up and down [my living room] and I walk up and down the outside terrace. I take a walk around the block. And I go upstairs and take a shower. I come back down and think. And I think and think. … I work every day. And even when you’re not thinking about it, when you get it going, your unconscious is cooking, once you’ve turned it on.”

In his youth, Allen discovered the joyousness of New Orleans jazz and has been a devotee ever since. It crops up frequently in his films, and he even named his daughter after Sidney Bechet. He practices his clarinet three times a week, and for many years, he played with his band at the Carlyle Hotel in New York on Monday nights. (Barbara Kopple’s 1997 documentary Wild Man Blues captures their European concert tours.) Allen’s use of music is part of what makes him such a romantic film maker—particularly that which helps to evoke his love of New York.

The authentic locations, particularly those captured in the late-’70s by the brilliant cinematographer Gordon Willis, now preserve in amber parts of a vanished city: the Pageant Book Store, the Thalia, the Cinema Studio, the Bleecker Street cinema, Metro theaters, the Carnegie Deli, and the Colony Record Store. Though tainted with a sentimental nostalgia, the abiding awe Allen feels for his city is everywhere in the films he shot there, wrapped in the music of Gershwin, Rodgers and Hart, and Porter, who provide the soundtrack to iconic scenes of horse-and-carriage rides in Central Park, and strolls beneath mesmerising skylines.

Allen is unapologetic about his tastes; he really does believe that the Gershwin-Porter-Rodgers and Hart songbooks are the apogee of American popular music. His distaste for rock and roll and the counter-culture crops up throughout his films, most memorably expressed during the scene in Hannah and her Sisters where Holly (Dianne Wiest) drags him to a local gig (“I love songs about extraterrestrial life, don’t you?” “Not when they’re sung by extraterrestrials.”). The embittered diatribes of Max van Sydow’s jaded artist in the same film, meanwhile, give voice to Allen’s disgust at the commercialization of American culture. And although he has always been a loyal Democrat, he enjoys mocking the pieties of condescending liberals fascinated by the glamor of criminality at a stylish “progressive” Hollywood party in Everyone Says I Love You.

An ability to cast effectively against type has allowed some of the actors he’s worked with to broaden their range and produce their finest work. Mia Farrow, the eternal waif, plays a stone-hearted, platinum-blonde gangster’s moll in Broadway Danny Rose and delivers one of her best performances. The gentle, flaky characters Dianne Wiest usually inhabits disappear in Bullets Over Broadway, where she lowers her voice an octave to play an extravagantly pretentious and self-dramatizing actress. Mira Sorvino, the sweet, tender-hearted young woman from Beautiful Girls, became a cheerfully dumb but worldly prostitute in Mighty Aphrodite with an accent that sounds like nails on a chalkboard. And while Allen has worked with his fair share of movie stars during his career, his most satisfying performances are often those given by gifted character actors, such as Lou Apollo Forte, the sweating and pudgily emotional Italian crooner Lou Canova in Broadway Danny Rose, or the once-popular comic Andrew Dice Clay who was handed a supporting role in Blue Jasmine.

Allen’s most memorable scenes do not tarnish with time. As he attempts to execute a bank robbery in Take the Money and Run, incompetent career criminal Virgil is stymied when the bank clerk says he can’t read his note and has to consult a colleague to figure out what a “gub” is. Mickey, the tormented hypochondriac Allen plays in Hannah and Her Sisters, is momentarily overjoyed after discovering that he does not have cancer, only to find that fear of death has been replaced by anxiety about the futility of life. He also asks his father why there are Nazis in the world, which elicits the impatient response: “How the hell do I know why there are Nazis? I don’t know how a can opener works.” In Bananas, Fielding Mellish hides a porn magazine among copies of Commentary, Time, and National Review as he approaches the counter, only for the sales clerk to call out across the shop, “How much is Orgasm?” In Annie Hall, Alvy remarks that Commentary and Dissent have merged into a magazine called Dysentery. Only a fraction of the film’s audience had probably even heard of all these highbrow magazines, but the jokes are still remembered and quoted today.

Humour is often juxtaposed with tenderness, sorrow, and poignancy. Isaac’s rueful farewell when Tracey leaves him at the end of Manhattan; Isaac and Mary silhouetted on the bench overlooking the 59th Street Bridge at twilight in the same film; Danny Rose’s feeling of betrayal when a client to whom he has been loyal moves on to greener pastures; Alvy Singer’s suggestion to Annie Hall on their first date that they kiss for the first time so they can digest their food better; Cliff’s crestfallen expression when he discovers that the girl he has been pursuing is engaged to his nemesis in Crimes and Misdemeanors, and the haunting words spoken by professor Levy at the film’s bleak conclusion; Annie Hall singing “Seems Like Old Times”; Steffi (Goldie Hawn) levitating and Joe (Allen) singing “I’m Through With Love” in Everyone Says I love You (Allen’s only musical, in which many of the cast members couldn’t really sing).

For an auteur most often praised for his plotting and dialogue, what’s remarkable about Woody Allen’s films is just how many moments of rapturous cinema they contain, when location, music, cinematography, performance, casting, and writing all combine to produce something wholly original and entirely cinematic. Allen is not simply a gifted writer and dramatist, but a consummate filmmaker who understands the possibilities of the medium as well as a virtuoso like Scorsese. As actor, writer, and frequent star, Allen is the driving force in his films, each of which provides us with an insight into his unique creative sensibility. He has eschewed adaptations, and his body of work speaks with one voice, irrespective of subject matter or genre.

IV.

Of the films I rewatched as I was preparing this retrospective, I found Broadway Danny Rose, Radio Days, and Crimes and Misdemeanors to be particularly rewarding. Broadway Danny Rose is a haunting and deeply affecting comedy-drama; an affectionate homage to the old comics and vaudevillians who populated the show business of Allen’s youth—a time when the side streets around the fabled RKO Palace were dotted with rooming houses for struggling performers. Danny Rose (Allen) is a small-time actors’ manager, representing a one-legged tap dancer, a one-armed juggler, a blind xylophonist, a ventriloquist whose lips always move, a parrot who sings “I Gotta Be Me,” and a couple who twist balloons into snails and giraffes.

Allen wrote the script from his life, based as it was on the experiences of his manager and mentor Jack Rollins. Rollins was so committed to Allen that he did not take a commission from him in the early years. It was Rollins, operating at first out of a phone booth, who urged Woody to do stand-up and babysat him for two years until he overcame his fears and began to enjoy performing. Danny Rose is the eternal innocent, with his Chai pin, the repository of ancient lost Jewish and Irish vaudeville and the schmaltz of the big-hatted red-hot mamas who waved white handkerchiefs at the old Sammy’s Bowery Follies. This was the joint where Allen’s father worked as a bouncer and bartender—and where my father took me when I was 12 years old—and Allen’s fondness for that vanished world is still palpable.

The film is partly drawn from Rollins’s experience with Harry Belafonte, who dropped him as soon as he achieved a modicum of success and even went on to ridicule him in his memoirs. Rollins gave everything to his clients, no more so (before Allen) than Belafonte, letting him live in his apartment with his family while he navigated the struggles of making it in show business. Danny Rose is likewise betrayed by his client, a has-been, temperamental Italian singer named Lou Canova, who is struggling to make a comeback in the nostalgia market. The film chronicles a day during which Rose is almost killed in his quest to help Lou, and ends with Canova being signed by a major talent agent and telling Danny he is leaving.

In Radio Days, Allen cedes centre-stage to a wider tableau. He doesn’t appear on screen but he narrates the story of his character’s childhood in 1944, so his presence is felt throughout. The child actor who plays Allen looks a lot like him, and the family in the film is a fictionalized version of his own. There are 40 speaking parts, some of whom appear for only a few seconds and are never seen again, but each of whom is memorable. The family’s radio sits at the heart of the film as an intimate companion to American households in the midst of wartime.

The period detail is so convincing that 10 minutes into the film it is easy to forget that you’re watching a movie made in 1987. Allen beautifully captures every aspect of old-time radio, beginning with a simulacrum of the buzzing musical score from The Green Hornet. Then there is the gentle parody of The Lone Ranger (retitled The Masked Avenger), whose swashbuckling hero is played on-air by Wallace Shawn, a character actor with a face made for radio. In reality, Shawn may be short and bald with an abbreviated chin, but his disembodied voice has made him a hero to millions of children as he cries. “Beware Evil-Doers!”

Commercials, radio soap operas, and other programs are likewise sent up with uncanny precision: sportscaster Bill Stern’s hyperbolic story-telling; the ventriloquists and their dummies who the audience can’t, of course, see (Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy); John J. Anthony’s sentimental counseling of dueling marital couples (renamed John Abercrombie’s Court of Human Emotions); the husband and wife team (like Tex and Jinx) chatting over breakfast from their glittering penthouse about all the glamorous celebrities they hobnobbed with at the Stork Club the night before; Carmen Miranda; Sinatra crooning at the Paramount before a screaming audience of bobby-soxers; young Woody’s first visit to Radio City Music Hall; and a vast array of other cultural artifacts from the period.

Allen’s extended movie family, crowded together in a Far Rockaway house, shout and fight, but they are depicted with affection. The father, like Allen’s real father, doesn’t want to reveal what he does for a living and his young son only finds out when he flags down a cab to find his embarrassed father driving it (“I loved him anyway and gave him a big tip.”). Aunt Bea (Dianne Wiest) is a luckless romance-hound who chooses one disastrous boyfriend after another—a quest that ends with a moving scene in which the young man she has been pursuing breaks down and confesses that he is still mourning his lover, Leonard. (“I see,” she says sadly before gently offering him a drink.)

Jackson Beck, the narrator of Take the Money and Run, broadcasts news of an actual event—the attempt to rescue an eight-year-old girl who has fallen down a well. Allen’s family listen to the story’s unfolding developments on the radio, their petty squabbles momentarily forgotten as they unite in the hope that the story will have a happy ending. That it does not serves to remind them of what they have in each other. As the terrible news comes through, Allen’s father holds the young boy tightly on his lap and both parents stroke his head.

In Wild Man Blues, Allen visits his actual parents and the reality is very different to the family depicted in Radio Days. His mother and father barely speak to each other and the atmosphere is frosty and bleak. They complain that their son, who was then at the height of his fame, has chosen an insecure profession when he really ought to have been a dentist or a doctor. His father is particularly clueless on this point. His mother does allow that her son is a “good person” but wishes he were “softer.” It is a painful visit for all concerned, audience included.

Crimes and Misdemeanors remains Allen’s crowning triumph, a film rich in feeling and dramatic irony that manages to combine Allen’s sparkling wit with a searching inquiry into human morality and responsibility. It tells two concurrent stories, the first of which concerns Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), a highly successful ophthalmologist, who is being blackmailed by his mistress (Anjelica Huston). The second story follows struggling filmmaker Cliff Stern (Allen), who seems to be the kind of person Alvy Singer might have become in middle age. Cliff has been hired to make a documentary about his brother-in-law, a vain television producer named Lester (Alan Alda), but he would rather be working on his own pet project—a documentary about renowned psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor Dr. Louis Levy.

Judah’s mistress is threatening to destroy his marriage and career unless he commits to her. In desperation, he arranges her murder with the help of his connected, lowlife brother (Jerry Orbach). At first, he is stricken by guilt and remorse, returning in memory to his Orthodox Jewish parents, who placed questions of moral behavior at the center of family life. Judah recalls that his father once told him, “The eyes of God are on us always.” Cliff, meanwhile, finds himself falling in love with Lester’s assistant, Hallie (Mia Farrow), who ends up rejecting him for Lester. Cliff is hardly a flattering self-portrait—he is judgmental and sarcastic about everything and everyone and obsesses about the faults of others; he is the scourge of pontification and career compromise yet his own life is a shambles; he is the better and smarter man and it avails him nothing.

Cliff and Judah finally meet in the film’s concluding scene—a wedding party thrown for the daughter of a mutual acquaintance. Judah has got away with the murder of his mistress and has returned to a married life of privilege and contentment, no longer tormented by a guilty conscience. Cliff, on the other hand, has been left lonely and heartbroken by Hallie’s rejection, he’s been fired by Lester (whose film he spitefully sabotaged), and the subject of his own life-affirming documentary has committed suicide. Invited by Judah to consider a hypothetical scenario in which a successful man kills his lover to protect his own wealth and status, Cliff maintains that we must all bear a burden of guilt for our crimes and transgressions. Not so, argues Judah, who says that if we learn to live with our misdeeds, we can escape their consequences altogether. He excuses himself to embrace his wife and accompany her to the dance floor, leaving Cliff despondent and alone.

In an interview with critic Richard Schickel, Allen said that he “just wanted to illustrate in an entertaining way that there’s no God, that we’re alone in the universe, and that there is nobody out there to punish you … that your morality is strictly up to you. If you are willing to murder and you can get away with it, and you can live with it, that’s fine. People commit crimes all the time, violent crimes and terrible crimes against other people in one form or another.” Crimes and Misdemeanors closes with the philosophy of Cliff’s subject, Louis Levy, which is both moving and perversely empty in the light of what we have just seen:

We are all faced throughout our lives with agonizing decisions. Moral choices. Some are on a grand scale. Most of these choices are on lesser points. But! We define ourselves by the choices we have made. We are in fact the sum total of our choices. Events unfold so unpredictably, so unfairly, human happiness does not seem to have been included, in the design of creation. It is only we, with our capacity to love, that give meaning to the indifferent universe. And yet, most human beings seem to have the ability to keep trying, and even to find joy from simple things like their family, their work, and from the hope that future generations might understand more.

Dr. Levy is played in the film by a real psychoanalyst and teacher, Professor Martin Bergmann. Levy, Allen told me, is a composite of Primo Levi and Bergmann himself, and his haunting words appear periodically throughout the film as a counterpoint to the unfolding drama, offering hope as the characters grope for meaning in darkness. Bergmann had never acted before but he was a characteristically inspired casting choice. He had enjoyed a career as an outstanding psychoanalyst, whose primary preoccupation was working with Holocaust survivors. He taught for many years at New York University, and his father, Hugo Bergmann, had been a noted philosopher in Prague and a close friend of Kafka and Martin Buber (after whom his son was named).

Read more from the author

I asked Allen’s casting director, Juliet Taylor, how she and Allen came to offer Professor Bergmann the role. “We wanted authenticity, as we do in all our films,” she said. “I went to a Christmas party of the New York Psychoanalytic Society and Institute. It was actually like a scene out of a Woody Allen movie. They were all wearing Earth Shoes and had goatees. A friend of mine recommended Dr. Bergmann.” Many of Levy’s lines were lifted from an interview Allen conducted with Bergmann while auditioning candidates for the role. “He took me into a room and asked me questions,” Bergmann later told the New York Times. “He wanted me to talk. He wanted me to talk about love, death and religion. I spoke about all of these topics for an hour and a half.” After he had finished answering Allen’s questions, Allen said, “You’ll do.” “He is not the example of a polite person,” Bergmann remarked, “but he is direct, which I appreciate more.”

I met with Dr. Maria Bergmann, Bergmann’s widow, after Bergmann died in 2014 at the age of 101. She told me that her husband had been dismayed to discover that his character committed suicide. In response, Allen agreed that Bergmann should be allowed to write the film’s concluding speech. “Woody let him speak his own words at the film’s conclusion because my husband said that the final words of the film had not really represented his views. And so there are a few words at the very end which are completely my husband’s. Those words replaced what Woody had written before. Woody allowed them to stand.”

After the film was released, Bergmann wrote Allen a note which read, “I am nowhere to be seen … And yet the impact of my work is felt throughout the film … Acting was never part of my fantasy life, but I can say that working with you was as close as a man my age can come to playing. So for that too I want to thank you…” Allen replied: “Dear Professor Bergmann, thanks for your note. I’m glad everything went well for you in your cinema debut. I wish I had known you earlier in my life, before I began the last 25 years of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. You might have been able to cure me. Best, Woody Allen.”

In a 2014 reassessment of the film published to coincide with its Twilight Time Blu-ray release, J. Hoberman wrote:

Mr. Allen’s title consciously echoes that of “Crime and Punishment,” and the comparison is not altogether specious. Like Dostoevsky’s, his characters are notably prone to agonized self-analysis, and seldom in an Allen picture have the stakes been so high. The various crimes and misdemeanors committed include murder, suicide and adultery (among other forms of deceit and betrayal), as well as the most unspeakable sexual act in Mr. Allen’s entire oeuvre; the movie ends with a wedding that brings everyone together to consecrate the notion of an unjust world.

An agnostic with regard to Mr. Allen when I first reviewed “Crimes and Misdemeanors” for The Village Voice, I thought I saw “startling intimations of greatness.” Revisiting the movie nearly a quarter-century later, I was struck by the skill with which he pulls off this unlikely amalgam.

Woody Allen directed his first film, Take the Money and Run, in 1969. Fifty-three years and a further 48 features later, he is responsible for a large, arresting, and frequently brilliant body of work that illuminates American life for future generations with specificity and originality. The times, places, and people his films have brought to life will remain long after the America that produced them has vanished into the mists of time. As we await the completion and release of Allen’s 50th feature, a review of his work affirms his place among the world’s great cinematic artists. Film-making is still a relatively young art form, but it has produced a handful of directors whose works of poetic beauty rival those of the literary greats. To the achievements of artists like Eisenstein, Chaplin, Rossellini, Bergman, de Sica, Ford, and Scorsese, we can now add those of Woody Allen, whose life’s work reminds us that we have no choice but to laugh at despair. “Life,” he once remarked, “is full of misery, loneliness, and suffering—and it’s all over much too soon.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article attributed the line “How the hell do I know why there are Nazis? I don’t know how a can opener works,” to Alvy Singer's father in Annie Hall. Quillette regrets the error.