Political

Political Moderates Are Lying

Change is wrought by those willing to lead or force others toward it. Which is why we are skeptical that most people truly believe every position they express.

Cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead once suggested that we should “never doubt that a small group of thoughtful citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” Mead is largely correct. Change is wrought by those willing to lead or force others toward it. Which is why we are skeptical that most people truly believe every position they express. Especially in public.

Do most people legitimately disagree with one another? Or are they merely conforming to supposedly dominant ideas? Though there are legitimate disagreements, we contend that modern American political tribalism has been artificially inflated by group-based conformity. That is, the moderate majority’s submission to the demands of dedicated partisans has created a mirage of polarization.

Most Americans are not impassioned ideologues, neither coopted by Soros nor swayed by Koch. According to a May 2018 Gallup poll, 43% of Americans considered themselves “Independents” while 26% and 29% considered themselves “Republicans” and “Democrats,” respectively. In fact, it wouldn’t be entirely inappropriate to characterize the average American as a disinterested political observer. A poll of Americans’ attentiveness to the 2016 election revealed that 38% of respondents observed the election “somewhat closely” while 22% followed “not too closely” and 8% “not at all.”

These results are not at all surprising given the tedium of politics. People have better things to do. And yet when it comes to specific issues, people are quick to take sides. Here, we describe how a small group of dedicated partisans have come to dominate the political scene, stoking the flames of mistrust and fomenting political tribalism.

Preference Falsifiers and Political Ringleaders

One of the most important concepts for understanding social behavior is preference falsification. Developed by economist Timur Kuran, preference falsification occurs when an individual publicly misrepresents their private views to fit into a social group. It is conformity for the sake of social self-interest.

And reputation matters. We falsify our preferences to maintain or improve our standing within a group. Conformity to group preferences yields approval, affection, and advancement within the group. Disobedience, however, is reputational forfeiture as we may lose our seat at the vaunted “cool table.” The punishment for nonconformity is disrespect and ostracism.

But preference falsification raises more questions than it answers. Why do the vast majority of us, despite our supposedly moderate beliefs, adopt more partisan viewpoints? How did these viewpoints become mainstreamed? Who decides the rewards and punishments for conformity and dissent?

In short, partisans run the show. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of Skin in the Game, discussed how this works in an essay titled “The Most Intolerant Wins.” He gives a simple example: the widespread use of automatic shifting cars. Those who can drive manual shift cars can drive all automatic cars. But the reverse isn’t true. Thus, the flexible manual shift drivers adapt to the inflexible drivers who can operate only automatic shift cars.

Taleb describes a Pareto distribution whereby a small number of highly inflexible individuals determine how a society is run. We might assume that the nature of democracy would mean the minority acquiesces to the whims of the majority. In reality, the majority’s passivity toward a policy or behavior is surpassed only by the minority’s rigidity toward it.

Committed ideologues are unshakable in their beliefs, unlikely to move toward the middle. On the other hand, moderates, less encumbered by bias, are more open to new ideas. Moderates are more likely to move toward the extremes than partisans are to move toward the middle. Given their flexibility, moderates tend to adopt the preferences of the intransigent minority.

But how does the moderate majority come to accept the preferences of an extreme minority? Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute provide an answer. The researchers, using mathematical modeling, found that there is a tipping point for when opinions held by a committed minority spread to the rest of the population. The tipping point is 10%. “When the number of committed opinion holders is below 10%, there is no visible progress in the spread of ideas…once that number grows above 10 %, the idea spreads like a flame.”

In short, how we behave often depends on how many people are behaving in that manner.

For a viewpoint to become popular, a minimum number of group members must first adopt it. Once this threshold is reached, the viewpoint becomes self-sustaining with more and more adopting it. Thus, the preferences of an intransigent minority are mainstreamed once enough moderates adopt them.

Following Taleb’s “minority rule,” political culture is driven by a small group of charismatic individuals. This makes intuitive sense as the actions of those in Washington drive the news cycle. Whether they be party leaders, activists, or intellectuals, these individuals are the heart and soul of a political movement. They draw the “party lines.” They create the tribe’s preferences and the tribe is willing to follow along.

The “minority rule” manifests rather mundanely in American politics. There is a lot of talk about hope, change, and making America great again. Slogans are indicators of what a party and political movement might become under a new leader. Often, a party comes to resemble the person who leads it. The leader determines what policies to support, what enemies to hate, what morals to espouse, and what hills to die on.

As a result, group preferences can change at the drop of hat. When Barack Obama openly supported gay marriage in 2012, his view not only became the de facto position of the Democratic Party but also produced preference changes across the US. Group preferences can also change radically over time. The Obama presidency significantly changed the political alignment of the Democratic voter base. According to Pew Research, between 2008 and 2016, Democrats have moved significantly leftward on a number of issues including racial discrimination, immigration, and the role of government.

This is not unique to Democrats, however, as Republicans’ political preferences have been “Trumpified.” YouGov polling indicates that between August 2014 and August 2017, Republicans’ view of Russia as an ally increased from 9% to 30%. Furthermore, Vladimir Putin’s favorability rating among Republicans increased from 12% to 32% between 2015 and 2017. And it’s not just Russia. Once supporters of free trade, Republicans are now increasingly against it, favoring steel tariffs.

This is not to suggest that political leaders are solely responsible for determining group preferences. Tribal preferences can be generated by self-righteous late night hosts, potty-mouthed actors, and this guy.

When it comes to formulating their own preferences, non-partisans tend to free ride on the ideas of the most available partisan, be it Kimmel or Schumer (both Chuck and Amy).

How Echo Chambers Encourage Preference Falsification

There’s no better time to join an echo chamber.

If everyone in your group holds the same viewpoint and constantly pats one other on the back for holding this view, then chances are you’re stuck in an echo chamber. There are no fundamental disagreements or internal debates. Acceptable ideas are “echoed” both because many people share them and because most refrain from speaking honestly. A group of likeminded individuals can reinforce one another’s tentative viewpoints through repeated interactions.

Consider this study by psychologists Serge Moscovici and Marisa Zavalloni. The researchers first asked participants their opinion of then French president, Charles de Gaulle. Next, participants were asked about their attitude towards Americans. Finally, the researchers asked the participants to discuss each topic as a group.

Discussion, it turns out, led individuals to become more extreme in their views. In particular, participants’ support for de Gaulle and dislike for Americans intensified as they learned that others shared these views. The researchers concluded, “Group consensus seems to induce a change of attitudes in which subjects are likely to adopt more extreme positions.” When we see our uncertain opinions echoed back to us, our beliefs strengthen.

We enjoy being around ideological compatriots. But this drive to associate with the likeminded has become excessive. Our communities are fragmented. And echo chambers are everywhere.

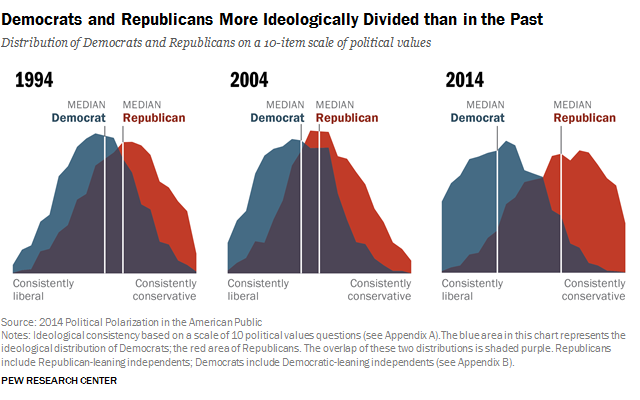

Today, polarization among Republicans and Democrats is staggering. Tracking 10 political values since 1994, the Pew Research Center discovered a 36-percentage-point gap between Republicans and Democrats. The gap was only 15 points in 1994.

This demonstrates a genuine movement towards polarization. As it relates to President Trump, nearly nine-in-ten Republicans (88%) approve of his job performance, compared to just 8% of Democrats.

In fact, the network science literature has revealed heightened levels of political homophily (“birds of a feather flock together”) on social media. Though these platforms were originally designed to bring people together, it is common to see social media users separate into two isolated communities, liberals and conservatives.

From what we’ve described, it is highly unlikely that most people within these groups are extreme partisans. It is instead more likely that moderates make up the rank and file. This raises an interesting question: how do moderates navigate this complex web of political tribes and echo chambers?

Simply put, they falsify their preferences. Most moderates conform to group preferences that have been established by committed ideologues.

Conformity is the key, here. Moderates must go along with the intransigent minority to get along with the group. In order to function within an echo chamber, less opinionated entrants must falsify their preferences so as to not upset those who decide the rules, rewards, and punishments. Moderates who agree with the gist of what the group stands for will often support fringe positions for the sake of group solidarity and reputational preservation. If you insist on telling the truth, your reputational goose is cooked.

American universities offer a clear example of how committed partisans can pressure moderates into falsifying their preferences.

In Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s piece entitled “The Coddling of the American Mind,” Haidt offers a brief yet significant revelation. He notes that the majority of his students are well-adjusted individuals willing to learn and confront their biases. It is, however, a small cadre of dedicated ideologues who insist that Haidt modify his language and issue trigger warnings.

Campus ideologues have created an “ethical” code of conduct for which the rest of the student body must follow. Aware of the reputational costs of defiance, the moderate majority conceal their true feelings, quietly nodding along to campus diktats. According to Gallup, 88% of students at Pomona College agreed that campus climate prevented them from speaking openly. In fact, one Pomona sophomore noted that defying campus dogma could result in being “socially shunned.” Surveys from the Foundation for Rights in Education and The Harvard Crimson also confirm this reality.

Similarly, our polarized politics encourages preference falsification. The best evidence of this stares us right in the face: President Trump.

Following the outcome of the 2016 American presidential election, many political observers asked one question: how could the polls be so wrong? Put simply, the polls didn’t actually measure how people truly felt.

Of the 61 national polls tracking a two-way race since October, only six gave Trump the lead.

In fact, the Princeton Election Consortium and the New York Times put Clinton’s victory at 99% and 85%, respectively. Only polls by the LA Times, IBD/TIPP, and the Trafalgar Group correctly predicted Trump’s victory.

Despite their confidence in tried and true polling methods, pollsters simply could not account for preference falsification on the part of Americans.

Even if polling organizations managed to collect a representative sample, they can’t always trust the responses that people give them. When a topic is controversial, respondents often modify their answers to align with what they perceive to be socially acceptable. This is called the social desirability bias.

However, when a large enough number of respondents falsify their preferences to the point where the results of the survey contradict the results of the event, this is called the “Shy Tory Factor.” This is named after British conservatives who hid their voting preferences from pollsters during Britain’s 1992 general election.

Conclusively, a report from the American Association for Public Opinion Research revealed that preference falsification among Trump voters played a part in the incorrect polling results. In fact, Robert Cahaly, a senior analyst at the Trafalgar Group, revealed that altering his polling methodology to account for shy Trump supporters allowed him to correctly predict the election’s outcome.

Characterized as racists and “deplorables,” Trump supporters felt hesitant to declare their voting preferences when polled. Publicly admitting one’s support for Trump would garner disapproval. Pollsters could not breach this veil of false reportage.

A Journey to Abilene

Political polarization encourages preference falsification which in turn reinforces political polarization. This is the reality of our politics. It’s not as though Americans believe every position they express in public. It’s more so that inflexible partisans have pulled us to the fringes of the political spectrum. In fact, fewer Americans (32%) occupy the political center in 2018 compared to 1994 (49%) and 2004 (49%).

Preference falsification artificially inflates political polarization. If our political preferences have been falsified then our differences might not be as pronounced or as authentic as we think them to be.

Nevertheless, group-based conformity is dangerous. Especially when most of us don’t actually agree with the directives of our intransigent overlords. Conformity can lead us down a path that most of us did not want to travel.

Imagine a group of people trying to make dinner plans. One person suggests driving to a restaurant in a distant city called Abilene. Another person, not wanting to travel very far but dreading an argument, says “sure.” A third individual, now thinking that her two peers want to go to Abilene, doesn’t want to be the odd person out. She agrees that Abilene is a good idea. This domino effect leads to everyone thinking everyone else wants to go to Abilene when in fact a consensus does not exist.

This is called The Abilene Paradox, described by management expert Jerry B. Harvey. It resembles the aforementioned echo chamber. But the Abilene Paradox is stranger. It consists of individuals who do not agree with an idea yet acquiesce because of their mistaken belief that a consensus has been reached.

Why is any of this important? Well, if enough people falsify their preferences then many of us will begin to mistake polite but dishonest assent for the honest truth.

Suppose you and I publicly supported a policy we privately despised. If neither of us publicly dissents then we’ll continue to openly support this policy, making it more plausible than it actually is. And neither of us benefits when our “support” for this policy paves the way for its implementation.

As Americans, we collectively arrive at Abilene when we truly believe political polarization to be authentic. When moderates acquiesce to the beliefs of partisans, they signal to the opposition their ideological inflexibility and unwillingness to come together. It may even be the case that moderates on either side agree with another. But if no one speaks their mind, similarities are never discovered and compromises are never made.

Under these conditions, political caricatures and derogatory terms are accepted as truth. We’ll have bought into the idea that those on the other side are actually “deplorables” and “snowflakes.” Binary thinking, ideological brinksmanship, and bad faith assumptions will come to define us. Most importantly, we’ll have succumbed to belief that we have nothing in common.

In short, perception will become reality. The preference falsification which props up political tribalism will in time legitimize it. Indeed, believing that we are divided may be indistinguishable from actually being divided.

Unfortunately, the evidence now increasingly suggests that our inauthentic differences are becoming authentic. We are succumbing to the sway of partisans.

According to the Pew Research Center, 44% of Democrats and 45% of Republicans hold a very unfavorable view of the opposition. In 1994, fewer than 20% in both parties viewed the opposing party very unfavorably. In fact, our dislike of our political opponents may be driven more by fear than it is by legitimate critiques. 55% of Democrats said that the Republican Party made them “afraid” while 49% of Republicans said the same about the Democratic Party. As per our point on perceived ideological inflexibility, a staggering 70% of Democrats and 52% of Republicans viewed the opposition as “closed-minded.”

Political tribalism has even distorted our view of who our real enemies are. A poll conducted by The Daily Beast revealed that Republicans were more favorable to Kim Jong Un (19%) compared to House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (17%). Similarly, Democrats viewed Kim Jong Un (82%) less unfavorably than President Trump (88%).

In the case of American politics, it is clear that an intransigent political minority have led us towards political tribalism.

If the actual truth becomes unfashionable to express, then we will all operate under the assumption that everyone else holds opinions they do not actually believe. Cutting through this collective mirage can save us from a trip to Abilene. Or worse.