Europe

From Welfare to Warfare

The leaders of NATO admit that they must pay for their own military defence but seem reluctant to put their commitments into practice.

Presidents of the United States have been generally kind to Western Europe since the end of World War II. They have been especially kind to the United Kingdom: partly because it was mainly from the UK’s loins that the US sprang and partly because of their common participation in the 20th century’s wars against a belligerent and imperialist Germany. (Winston Churchill remains an American hero.) In the post-war period, other European states and leaders—even the often anti-American General Charles de Gaulle—also at least tacitly acknowledged the primacy of the US within a West united by fear of the Soviet Union.

Within that commonality, the US was not only first among non-equals, but the only state with a large military budget and efficient armed forces. The UK and France had and retain nuclear weapons but have since shrunk their conventional forces even further. By 2017, soon after President Emmanuel Macron first took office, then-Chief of General Staff General Pierre de Villiers was warning that “he could not guarantee the sustainability of the defence model that could ensure the security of France.” In the years since, the once extensive French military presence in Francophone Africa has also been radically downsized—a shift which the British had already made.

These developments were all part of a “peace dividend,” based on the assumption that the end of the Soviet Union and the apparent democratisation of Russia had removed the need for large-scale defence of the Western states. The US, by contrast, had become the world’s policeman and continued to spend billions on the defence of Europe: successive presidents pleaded for a rebalancing of expenditure between the US and Europe, but were ignored.

On 14 February, US Vice President J.D. Vance told the Munich Security Conference that he and President Trump shared the view that Europe was reneging on its democratic values, especially that of free speech. And he added his dismay at the fact that Europe’s politicians were determined to destroy any political agency for the New Right parties—often described as “far” or “hard” Right—to the extent of banning their aspirants for office from competing, as they did when they annulled the first round of the Romanian presidential election.

Banning politicians who represent populist parties is wrong, Vance told them: “We do not have to agree with everything or anything people say, but when political leaders represent an important constituency, it is incumbent on us to listen.” Speaking in Poland at the same time, US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth’s message to Europe was “now is the time to invest, because you can’t make an assumption that America’s presence will last forever.”

Officials and scholars responded to Vance and Hegseth’s speeches with shock and rejection. Then German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said that “Germans will decide their democracy,” and refused to recognise anything positive in the Vice President’s speech—even though much of what Vance said was observably true.

The senior officials in Trump’s administration know the President shares their views of Europe. Indeed, he set the tone in his first administration. In 2019, the Economist observed, “Mr Trump appears to promise the biggest rupture in transatlantic relations since 1945.” That attitude has been turbocharged in his present term.

So, are the European states going to rise to the challenge and substantially increase their defence spending and develop joint intelligence networks with US? Still more importantly, will they work to quickly standardise their technologies and weaponry, which differ widely among the European states?

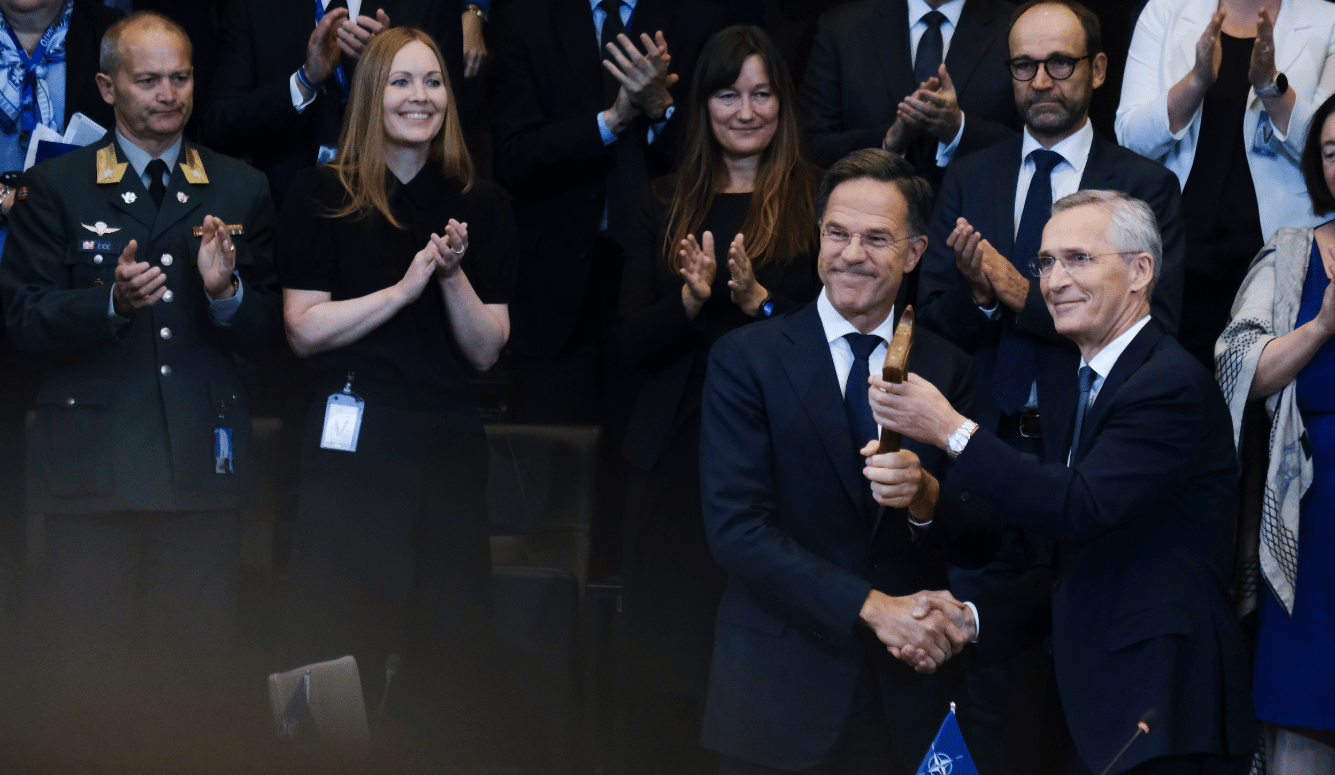

The most important challenge facing Europe is not Trump’s barrage of demands, but the threat of an expansionist Russia. And, while European politicians spout rhetoric about the need to be able to defend themselves, they seem unwilling to take the necessary concrete steps. Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez has refused to commit to raising defence spending to 5 percent of GDP—the target Trump demanded. The other NATO members agreed to this target at a summit in the Hague on 25 June. However, whether they are seriously committed to this goal remains in doubt. As one source told the Financial Times, “Spain could have quietly accepted the summit declaration’s ambiguity and long timelines, which in effect soften its 5 per cent of GDP spending target, without making a fuss.”

In France, the months-long struggle between Prime Minister François Bayrou and his parliamentary opponents on both Left and Right continues. The two sides have been unable to come to an agreement on defence expenditure, while the distrust between Bayrou and President Macron, who appointed him, has continued to grow. Marine Le Pen, the co-leader of France’s most popular party, the New Right Rassemblement National, has stated that she supports Ukraine in its war with Russia but rejects a unified defence strategy.

Of the major states, Germany, under the new Chancellor Friedrich Merz has shown the strongest signs that it intends to make up for years of having had no military worth speaking of by spending billions on soldiers and weaponry. Meanwhile, Italy, which had been a conspicuous laggard in this regard for decades, has promised to finally increase defence spending from 1.49 percent to two percent of GDP by the end of this year, and to strive for further increases in the future (though these have been left undefined).

At the NATO summit, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer committed to five percent defence spending. His government had earlier introduced a Welfare Bill, aimed at cutting £5 billion (US$6.9 billion), primarily by tightening up eligibility for personal independence payments, to allow for a rise in defence spending. The proposal enraged 108 Labour MPs—enough to overturn Labour’s large parliamentary majority—who argue that their Party should not prioritise weapons over welfare and threatened to vote against the Bill. At the last moment, the Bill was substantially changed, postponing the cuts and has now passed in an atenuated form. However, the media consensus on both Left and Right is that the Prime Minister’s authority has been badly damaged.

Despite the assurances of the politicians at the NATO summit, decades of dependence on the US for defence have left European leaders struggling to retain high welfare spending, while creating the impression of preparing for a future war. Only where the Russian threat is best understood—in the states that were once part of the Soviet empire or share a border with Russia—is the case for defence expenditure relatively easy to make. The three small Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and the Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, have all ramped up their defences. In Lithuania, the government has reintroduced military conscription, doubled the size of its armed forces and pushed defence spending up to 3.45 percent of GDP—one of the highest rates in NATO. Poland has increased its defence spending from 2.7 percent of GDP in 2022 to 4.2 percent in 2024 and it is projected to rise to 4.7 percent in 2025—the highest level of any European country.

No-one knows if this fevered activity will be needed, but the received wisdom, especially among the Baltic and the Nordic states, is that it is better to be safe than invaded. Katarzyna Zysk of the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies says that “Russia wants to achieve the objectives which it has been pursuing systematically since the early 2000s, namely, expanding Russia’s sphere of influence and undermining the US as a dominant international force, especially in Europe... they indicate that Russia is preparing for a large-scale confrontation.”

European accounts of the threat are stark. Among the most authoritative of these is the annual report from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy in Germany. In September 2024, they noted that “Russian military industrial capacities [have been] rising strongly in the last two years, well beyond the levels of Russian material losses in Ukraine,” while in key European states such as France, Poland, the UK, and especially Germany itself, there has been a “substantial decline in available stocks of key weapon systems… over the last decades.” The report urges “a need to focus on speed in procurement, on cost effectiveness through economies of scale in an integrated European market, on innovation, and on technological superiority.”

Over the course of decades, the majority of Europe’s citizens grew to expect that peace and at least relative affluence would last well into the future. Politicians on both sides of the aisle moulded their manifestos and actions to serve the happy many.

In his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama depicts what Friedrich Nietzsche described as “an archetype of liberal passivity,” one who seeks “mere materialistic comfort,” the opposite of Nietzsche’s Übermensch. This seems like a fitting image for our current moment. While Donald Trump seems to be striving for Übermensch status, the Europeans are in danger of becoming last men, passively awaiting their own destruction.