Russia

Eight Hundred Years of Russian Despotism: An Interview with Orlando Figes

In a new book, the historian traces modern Russian aggression to an apocalyptic mythology rooted deep in the nation’s past.

The text that follows is adapted from a July 3rd, 2023 podcast interview conducted by Quillette’s Jonathan Kay with historian Orlando Figes, author of the newly published book, The Story of Russia.

Jonathan Kay: So I’m going to start off with a big question. In your book, you talk about the “sacralization” of the Russian Czars’ authority as a legacy of Byzantium. And until I read your book, I really had no understanding of how much Orthodox Christian theology had mixed with Slav ethnic populism to create this kind of theocratic—and maybe even apocalyptic—vision of the Russian Empire as the “third Rome.”

Can you explain what that means—the third Rome? You used that phrase several times in your book.

Orlando Figes: This concept of the third Rome, which is at the heart of a Russian sense of mission in the world, presents Russia as a sort of messianic land—a little bit like Israel, I guess—in the medieval theology that was adopted by Ivan the Terrible, who was the first to be crowned Czar. It served to reclaim, after all those years of Mongol occupation, the Byzantine legacy, symbolically, through his coronation.

The idea was that after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moscow was the last true seat of Christian orthodoxy. And there would be no other. The idea was that the west lay in a fallen state. It was fallen from a state of grace that Russia still retained by virtue of its orthodox religion.

Therefore, the true salvation of humanity lay with holy Russia. And this idea, of Russia as a providential land chosen to save humanity, is at the very heart of both the Russian Empire, and, later, [Russian] communism. It’s deeply connected to the sacralization of power because it presents the Czar as the direct manifestation of God on earth—as Ivan the Terrible saw himself. It was his mission not just to save humanity, but also to prepare his people for the final judgment.

So the Czar is potentially also a tormentor of his people, in order to make them worthy of that messianic role. Putin acts in this tradition. He sees Russia as having a mission that goes beyond its strict territorial boundaries. In the 19th century, similarly, Nicholas I claimed Russia had a holy mission to liberate the Orthodox Christians of the Ottoman Empire. And indeed, he saw his mission going so far as to liberate Jerusalem.

J.K.: I’m going to quote something from your book, which I found remarkable. This is a description of what happened in 1552, after Ivan the Terrible’s forces conquered Kazan:

A large horizontal icon called The Blessed Host of the Heavenly Tsar was painted facing the Czar’s throne in the Dormition Cathedral. Known as The Church Militant, it shows the mounted figure of Ivan following the Archangel Michael in a procession of Russian troops from the hell-like burning of Kazan to Moscow depicted like Jerusalem, where they are received by the Madonna and Child. The iconography borrows from the Book of Revelation, in which Michael defeats Satan before the Apocalypse. Ivan appears as a new King David and the Russians as God’s Chosen People, the new Israelites.

This kind of image, if placed in the Western idiom, sounds like something out of the age of Richard the Lionheart. Yet this Russian scene is from the 16th century—at a time when the West already had the printing press. It’s the dawn of the Elizabethan age. In the West around this time, people are talking about things like parliaments and theories of taxation and private property. There’s something strangely anachronistic about the world portrayed in The Church Militant.

Western philosophers and politicians were then trying to separate the abstract state from the people who ran it. Your contention in the book is that this separation has never really been clearly defined in Russian history.

O.F.: You're absolutely right. And with The Church Militant—I mean, there you have it. Everything we discussed in your previous question is there contained in that one icon.

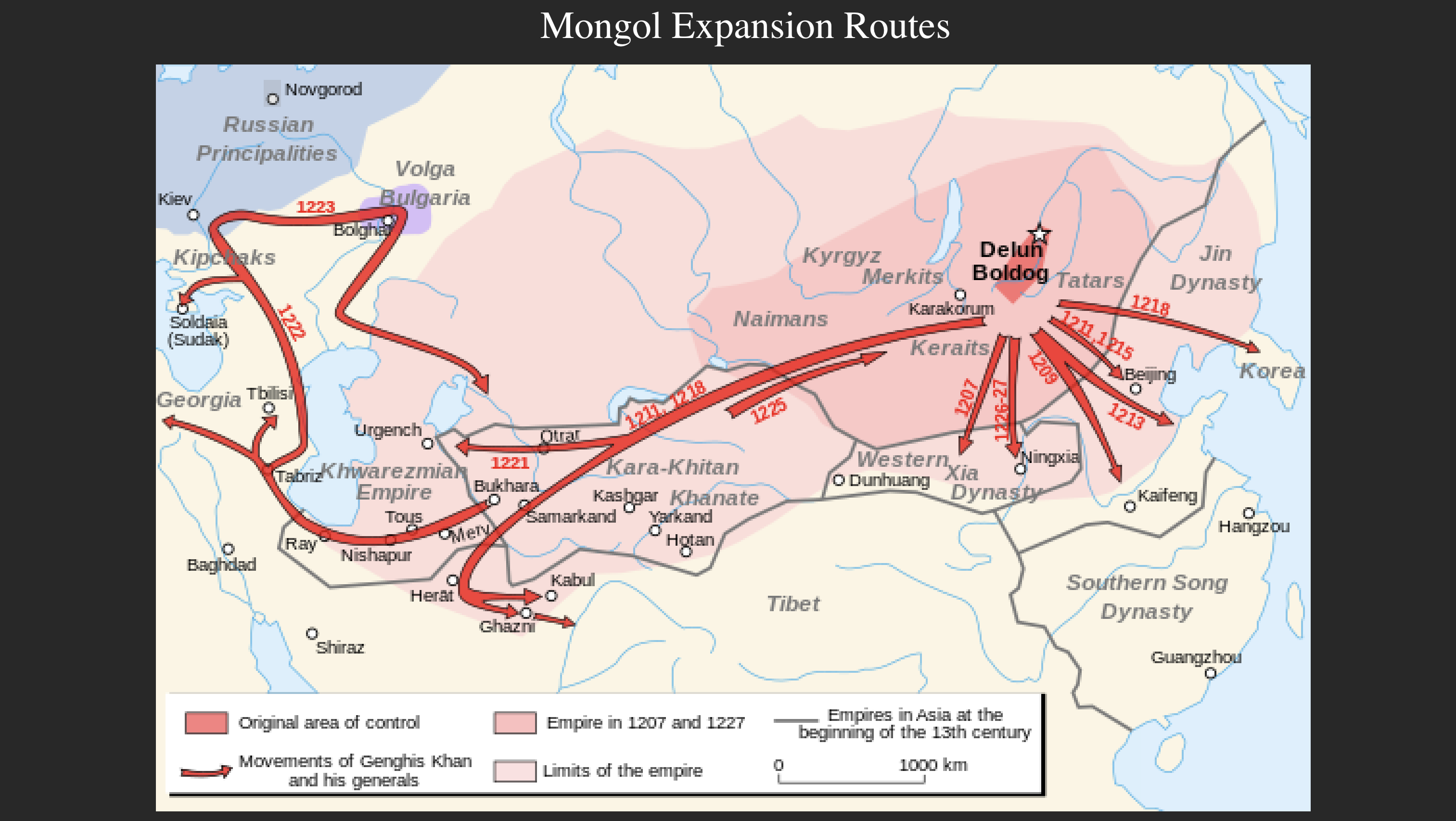

What Ivan was suppressing in Kazan was a whole kingdom—the khanate—that had remained from when the Mongols had swept over Russia in the 13th Century. This was one of the last offshoots of the Golden Horde, as the Mongol occupation of Russia was known. Ivan’s victory was seen as a kind of providential deliverance, ending more than two centuries of Mongol rule over the Russians, which had entailed, at least periodically, the ransacking of towns and the burning of churches.

This was the sort of precarious existence that Russia's Christian civilization endured on a Eurasian steppe peopled by pagans, Muslims, and, in some cases, Jews. The idea here was that the Russians were carrying the Christian mission.

And yes, the idea of the state being fused with the Czar, that absolutely is at the heart of my argument about what makes Russia very different from the Western tradition. As you say, around the time of the Renaissance, and arguably earlier in most Western states, there was a growing separation between both King and church, but also between the idea of the King’s office and the idea of the king himself.

That separation didn't happen in Russia, partly because of the Byzantine tradition where church and state are fused and represented through the holy body of the Tsar; and partly because of what I think of as the other great structural continuity in Russian history, namely patrimonialism [a form of governance in which all power flows directly from the ruler].

The idea of state in Russia, which is expressed as gosudarstvo (государство) in the Russian, is completely fused with the idea of the sovereign, the gosudar (государь), which means not just a ruler, but a sovereign or anyone who has a patrimonial property over land—which is, actually, the source of the concept of power itself in Russia.

If you take the word for “power” in most European languages, it comes from the idea of autonomous action, which, eventually, becomes commensurate with the idea of individual liberties. But in the Russian tradition, the word for power is vlast (власть), which comes from the word vólost, which is the word for a territorial entity in which one would own the land and its people. So this is a patrimonial concept of power, which situates the state in the patrimony of the Tsar.

Consider: In 1897, for the first time, the Russians carried out a national census. And Nicholas II, the Tsar at the time, registered himself, under the category of “occupation,” as “Owner of Russia.”

J.K. My grandparents on my father's side are Russian. And my mother made an effort to learn Russian in order to communicate with my grandmother, her mother-in-law, because my grandmother’s English was never great, even after being in Canada for many years. But my mother, who had learned German and Yiddish and Hebrew, threw up her hands when it came to Russian, because she said that every marauding gang on horseback brought its own set of verb conjugations into the language, and she just despaired of it.

And of course, we are talking here about the invading Mongols. How much of the Russian sense of vulnerability, the Russian psyche, Is based on the sheer flatness and openness of the country. There are no natural geographical boundaries that protect it. How far does geography go in explaining the Russian mindset?

O.F.: Well, I mean, there have been historians with great reputations who've made this the absolute key determinant of looking at Russia. One always has to start with geography—including the problematic nature of Russia’s boundaries.

The fact is that it is a flat Eurasian landmass stretching from the Carpathian Mountains [in east and central Europe] and the Urals—though I would say that even the Urals are more like hills in many places. They couldn’t really serve as a defensive point against Asiatic tribes and Mongol horsemen, who were pretty advanced in their day and had no trouble sweeping across Russia.

So that left a sense, according to George Vernadsky—who was probably the historian who, more than any other, emphasized the importance of the Eurasian element to Russia’s development—that the only way the Russians could defend themselves against the Asiatic hordes was to just move into the whole of Asia.

On Russia’s Western side, the insecurity was more problematic, because there—in contrast to Asia from the 16th century onward, where Russians had gunpowder and the Siberian enemy only had bows and arrows—they were up against much more powerful European states: the Swedes, the Poles, the Lithuanians, and then the Germans.

And they found themselves with growing paranoia, as they couldn't defend their open vulnerable borders in what we would call the Black Sea front. So the conquest and assertion of Russian power over Ukraine, and the conquest of the Blacks Sea area by Catherine the Great in the late 18th Century, and then the defeat of the Crimean khanate—all of that was important geopolitically to the Russians. They felt that otherwise, the Black Sea area would become a threatening sphere due to the presence of Western powers—mainly Britain and France—following the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

This Black Sea area was also a fault line, if you like, between Christian Russia and the Muslim cultures of the Caucuses and the Crimean area. The fact that this fault line ran right across the southern border of Russia, as it was in the 18th century, opened it up to Western infiltration through Muslim tribes resisting Russian occupation.

These Russian actions set up the western border of Russia that led to many international instabilities, including some of those we are seeing play out on our screens right now.

J.K. Your treatment of the history of Russia and Ukraine goes all the way back to something called Kievian Rus, the Viking-descended proto-Russian civilization that emerged in the late 9th century in what is now Ukraine—a civilization led by a highly mythologized figure claimed by both the Ukrainians and Russians, named Vladimir the Great.

At that time, Kiev (or Kyiv) sat at the center of this early civilization. And yet the word Ukraine, as I understand it, descends etymologically from the Russian word for hinterland. Can you explain that?

O.F. Yes, meaning “edge” or “borderland”—okraina (окраина). And I wrote this book with the idea of focusing on the mythologies that have structured the Russian understanding of their own history—because it seemed to me that Putin had been sending clear warning signals that he was going to deny Ukraine’s right to exist as anything but a border region of greater Russia. As he sees it, that is what it has always been—at least until the formation of the Soviet Union, when the communists gave it an artificial statehood.

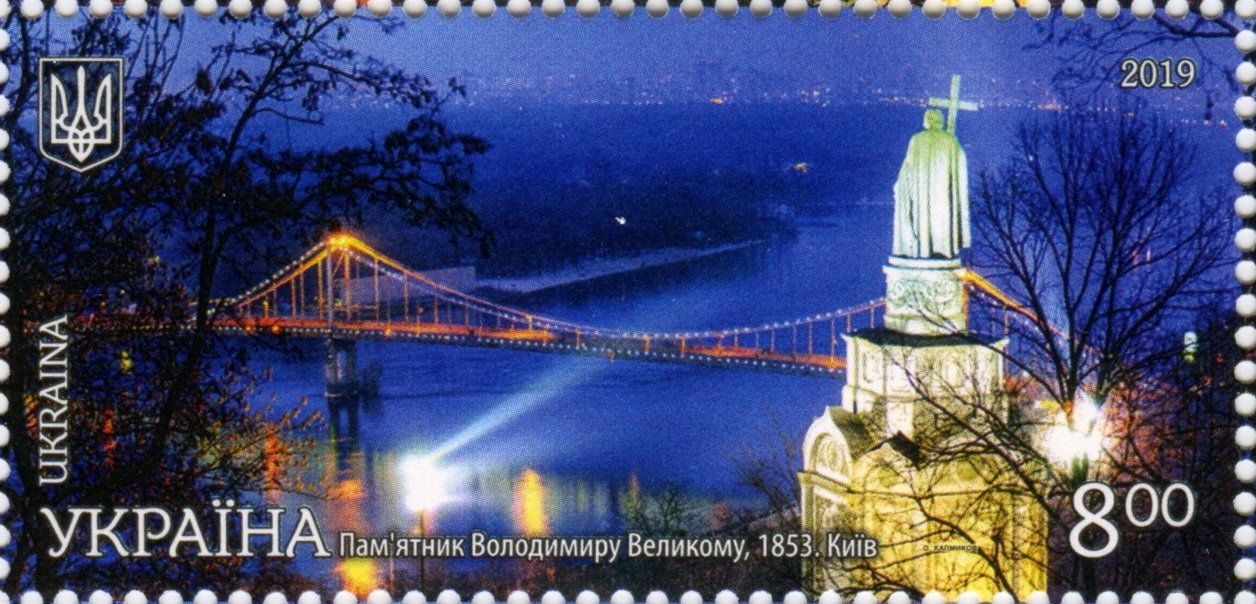

And that explains the symbolism of Putin building a statue in 2016 of the great Vladimir—the “equal to the apostles,” as he’s known (равный апостолам) who in 988 A.D. converted both himself and his people to Christianity in the Crimea. In this manner, as Putin sees it, the ruler of Kyiv joined Byzantium and became the founder of the Russian state. This is part of saying that Ukraine doesn’t exist as an independent entity.

But in fact, there was already a statue of the Great Prince Vladimir in Kyiv itself, built in 1853 when Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire. By the end of the 19th Century, that statue had already become a sort of informal focus for Ukraine's independent sensibility, as being different from Russia. This remained true after 1991, when the Ukrainians set about building their nation on the idea that they were not part of Russia.

On this view, Kievian Rus was the beginning, not of Russia, but of Ukraine. And it was this that became the entrenched view in Ukrainian nationalist ideology. And so in 2016, the country’s president, Petro Poroshenko responded to the unveiling of the statue in Moscow by saying to Russia, in effect, “You are stealing our history.”

All of which to say, the origins of the war in Ukraine are deeply historical—even if, by now, it's probably more to do with Putin just fighting the west for its own sake, because be knows he can’t really conquer the whole of Ukraine.