Politics

The End of NATO, or The Sixth Impossible Thing

The Trump administration has liquidated the postwar international order.

As I absorbed the collected enormities disgorged by the second Trump administration on the topics of Ukraine and NATO over the last few weeks—first in Brussels, then in Munich, then in Washington, then in Riyadh, and finally in the Oval Office—I was reminded of the following exchange from Lewis Carroll’s 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass:

“There’s no use trying,” Alice said to the White Queen: “One can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Reality can sometimes seem even stranger than fiction, and the second Trump administration has done what many people supposed to be six impossible things within the first month of its tenure. The upshot is that we are now living in a post-NATO world where black is white, up is down, friends are foes (and vice versa), and once-unthinkable impossibilities have become our new reality.

Six Impossibilities

The first impossibility accomplished by the new administration saw Donald J. Trump and J.D. Vance win the only two elected offices of the US executive branch with a campaign of wild lies about the November 2020 election and what happened at the Capitol on 6 January 2021. After the inauguration, they turned those lies into loyalty tests required of nominees to plum jobs in the administration, including on the National Security Council staff and the Policy Planning staff at the State Department.

Second, on his first day in office, the president used his pardon power to release a loyal and violence-prone cohort of 1,600 insurrectionists.

Third, the White House won Senate confirmation of manifestly unsuitable nominees to head executive-branch departments and agencies, many of whom are openly hostile to the stolidly apolitical missions of their own offices.

Fourth, the administration fomented a constitutional crisis by illegally impounding funds authorised by Congress, illegally firing senior civil-service employees without due notice or cause, and empowering a legally non-existent office—the DOGE—to carry out the most massive personal-information hack of the US government in history. The White House seeks a confrontation with the Supreme Court over this because it believes—perhaps correctly, perhaps not—that the 1 July 2024 SCOTUS decision on presidential immunity will cause Chief Justice John Roberts to back down. And if he does, the core checks-and-balances mechanism of US democracy—the separation of powers—will shatter. And if that happens, the US government will become a de facto autocracy.

Fifth, the administration fomented that crisis by using the DOGE to destroy the regulatory capacities of the federal government, purporting that its activities were devoted to greater government efficiency. The real purpose of this project is the creation of a corporate oligarchy within and protected by a weaponised para-government itself.

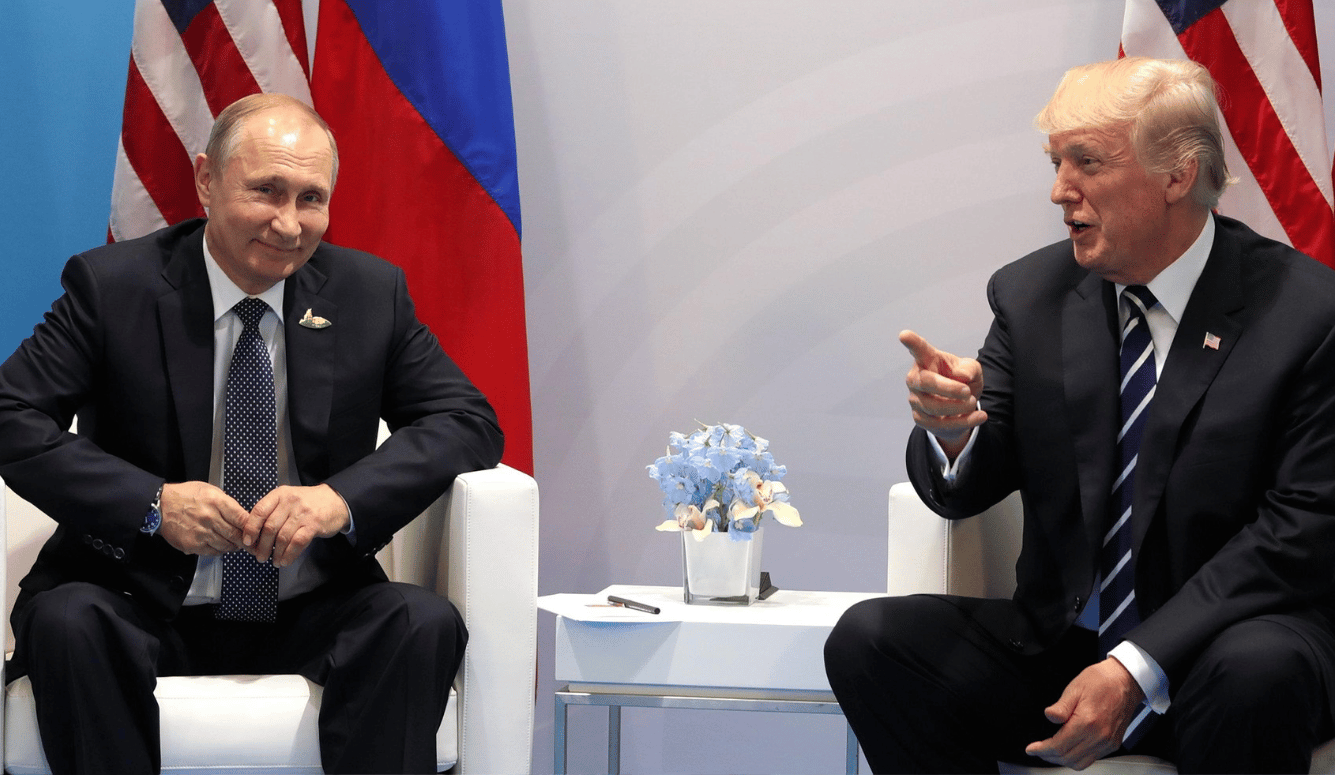

And sixth, the administration has effectively liquidated the central US alliance of the postwar era, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), and then joined with Russia to enable the consolidation of a West-facing sphere of influence. That sphere of influence may expand or it may not; if it expands, it may expand slowly and modestly, or rapidly and immodestly. The Trump administration does not care either way. In return, the administration wants rights to invest in Russian energy industries and to partner in the colonisation of Ukraine. Presumably, given the stunted syntax of this logic, it also hopes to reach an understanding with Vladimir Putin that Russia will henceforth respect an expanded US sphere of influence.

Two strategic benefits seem to be expected to emerge from cutting that deal. First, it is supposed to assuage Russian fears of American enmity and disincentivise further aggression by Moscow against the West. Second, Russian cooperation with China is expected to diminish. Are these realistic expectations? The idea that the Russian regime will forgo easy pickings because its last bout of aggression was obviously just defensive in nature is, well, unpersuasive. Even less persuasive is the idea that Russia will moderate its relations with China because America offers the Russians more than the Chinese and insists that Putin choose between them.

Russia may well opt for a respite once Ukraine is Belarusised, but if it does, it will be a consequence of exhaustion and inherent weakness. Putin may moderate relations with China because he fears China getting the upper hand, and he may finally understand the utility of the West in balancing an Eastern threat—an obvious thought that seems to have escaped him these past years. But Putin will not do either of these things because the Trump administration has exercised any leverage over him, since it plainly has not.

Cravenly conceding the pot before the hand has played out is neither shrewd nor subtle. Effective deterrence requires strength not unforced displays of weakness. If this is Trump’s idea of peace through strength, it is hard to imagine what peace through weakness would look like. I am reminded of Robert S. Vansittart’s tart observation: “In diplomacy you can ‘solve’ anything by giving way.”

The Meaning of the Sixth Impossible Thing

The first five of these impossible things complement and pave the way for the sixth—the demolition of NATO. As anyone who has worked high enough in government knows, the foreign policy of a great power is always at least partly an extension of its domestic politics and a projection of its wider political culture. So, then, what of the particular projection we witnessed these past weeks?

NATO still exists on paper, but operationally, it has been killed in a four-act drama followed by a macabre after-party (ongoing). There will be those who insist that NATO’s Article V guarantee is still alive and well, and that Ukraine is an exception because NATO real-estate is not at risk. Should the Russians attack a NATO member-state, they claim, Article V will rise and shine. This argument is backwards.

How can a US Article V guarantee remain credible in the event of some theoretical future contingency when it has been disavowed in the context of an extant shooting war, more or less contained outside the alliance’s borders? The very essence of extended deterrence—which is what Article V is supposed to ensure—is that the alliance leader will credibly backstop risks in ways that reduce those risks. If it won’t do that when risks are modest, it is hardly likely to do it when the risks are much greater. Yes, on 12 February, US Defence Secretary Hegseth reaffirmed the “US commitment to NATO,” which presumably implied a commitment to Article V. But the US president then attached a condition; namely, that European members of NATO each fork out five percent of GDP to pull their weight. The implicit threat being that those who fail to do so will forfeit the guarantee of US protection.

This is absurd. The United States currently spends just 2.9 percent of its GDP on defence, and looks to be planning reductions, not increases, in that percentage. So Trump knows that his five percent demand will not be met, thereby providing him with a pretext to offload US responsibility for European security altogether, which is what he wants to do anyway. During his first term, Trump made no secret of his wish to destroy NATO, or at least to pull the United States out of the alliance. He was only prevented from doing so by the presence of wiser Republicans like H.R. McMaster, James Mattis, John Bolton, John Kelley, and a few others.

In any event, there is no fooling Friedrich Merz on this point. One of the first things Merz said after Germany’s 23 February election made him Bundeskanzler-apparent was that Europe must make itself independent of the United States, which Europeans increasingly see as not merely uninterested in continuing alliance relations but as a potential threat. He and they are correct, and any lingering doubts about the full-frontal nature of the US foreign-policy upheaval were dispelled by the UN General Assembly episode of 24 February. In a draft resolution on Ukraine, the US adopted the Russian position on the war, thereby putting America at odds with nearly every democracy on the planet.

The Play and the Afterparty

In the light of which, let’s review the aforementioned four-act performance with the benefit of a few weeks’ hindsight.

In Act I, Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth told the Ukraine Defence Contact Group in Brussels on 12 February that European members of NATO must lead from the front, that the United States would neither put troops on the ground nor apply an Article V guarantee with respect to anything the allies might do to help Ukraine. He added that NATO membership for Ukraine was off the table, and that Ukraine’s goal of reclaiming all its sovereign territory is unrealistic and is not supported by the US government. In return for these pre-emptive concessions to Russia, the United States asked for—and therefore received—nothing in return.

Why did the Trump administration do this? Hegseth explained that the national priority must be securing America’s own borders and deterring “communist China,” which he called “a peer competitor ... with the capability and intent to threaten our homeland and core national interests in the Indo-Pacific.” In short, European security is Europe’s obligation and problem, and the US government will not pledge its support should the continent’s deterrence or actual security be threatened. Hegseth’s subsequent reaffirmation of the US commitment to NATO meant nothing. For those not wilfully blind to the obvious, NATO without US security guarantees is not NATO at all. For the time being, at least, the alliance has been reduced to a coffee klatch able to bring little more than a butter knife to a gunfight.

In Act II, Vice President Vance appeared at the Munich Security Conference on 14 February, where he briefly repeated Secretary Hegseth’s points about security. But he spent most of his time at the dais channelling the spirit of fascist theorist Carl Schmitt. His audience might have wondered why they were listening to a sermon on democratic probity from a man who has sworn he would have done—and will do in future if necessary—what Vice President Mike Pence refused to do on 6 January 2021; namely, defy the law to void the results of a free and fair American election.

In Act III, no words were spoken in public, but they did not need to be. Hegseth and Vance brought a young demagogue and conspiracy crank named Jack Posobiec with them to Europe, presumably so that the assembled Europeans would not misunderstand Vance’s excessively tactful speech. During his appearance on a panel at last year’s Conservative Political Action Conference, Posobiec announced: “Welcome to the end of democracy. We are here to overthrow it completely. We didn’t get all the way there on January 6, but we will endeavor to get rid of it.” Vance, meanwhile, pointedly refused to meet with the German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, and met instead with Alice Weidel, the head of the aggressively pro-Russian Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD). This was not an oversight or a coincidence.

The blindsiding of the NATO allies delivered an unmistakable message: We don’t care about you, we don’t like you, and we enjoy it when you whine. The exclusion of Ukraine delivered an equally clear message: Your sovereignty is about to disappear and we would be happy to hear you whine about that too.

In Act IV, President Trump initiated a call with Vladimir Putin, and presumed to negotiate the fate of Ukraine without that embattled country’s approval or participation, and without the foreknowledge or participation of America’s NATO allies. Hegseth did not mention this call when he spoke and Vance made no reference to it either, which suggests they believed it was no one’s business but that of the United States alone. The blindsiding of the NATO allies delivered an unmistakable message: We don’t care about you, we don’t like you, and we enjoy it when you whine. The exclusion of Ukraine delivered an equally clear message: Your sovereignty is about to disappear and we would be happy to hear you whine about that too.

The same day, a package from Washington landed on the desk of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, in which President Trump demanded US$500 billion in what amounted to reparations from Ukraine, and first-right shares to Ukrainian minerals, oil and gas, port fees, and much else. Trump told US news sources that if Zelensky were unwise enough to reject this deal, his country would be delivered to Russia on a plate. This is just extortion, mafioso-style, with an extra dash of loan-sharking: a deal you cannot refuse without imperilling your own life and the lives of everyone you care about.

That document was prepared by private lawyers in New York, not by anyone in the US government in Washington. President Zelensky accurately pronounced it a colonial document. Trump then accused Ukraine (not Russia) of starting the war, described Zelensky (not Putin) as a dictator, and declared that Russians (not Ukrainians) are the conflict’s true victims. Ordinary observers gasped while the MAGA herd brayed its approval.

As to the afterparty, Trump’s erratic behaviour toward Zelensky has resembled that of a frenzied Adderall addict. Days after Trump called Zelensky a dictator, Trump appeared to withdraw the remark during a press conference with UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer. Then, when Zelensky headed to Washington to sign a vastly watered-down version of the extortion demand he was originally given, he was yelled at by the US president and his deputy during a bizarre photo call in the Oval Office—ostensibly for failing to be sufficiently deferential to his hosts.

The new United States government only has use for servile partners willing to accept a strictly transactional relationship. In the MAGA political economy, things like cultural affinity, moral authority, and political values are now worthless. Even Niall Ferguson, who has leaned hard into MAGA in recent months, has taken exception to the spiteful humiliation of Ukraine. In response, Vice President Vance accused him of peddling “moralistic garbage.”

This is moralistic garbage, which is unfortunately the rhetorical currency of the globalists because they have nothing else to say.

— JD Vance (@JDVance) February 20, 2025

For three years, President Trump and I have made two simple arguments: first, the war wouldn't have started if President Trump was in office;… https://t.co/xH33s6X5yf

Like Putin, the Trump administration sees the world through a 19th-century lens. The US-wrought postwar order, it believes, has become harmful to US interests. It assumes and hopes that great powers will now pursue deal-making and advantage over the heads—and often at the expense—of smaller and weaker states. It knows but doesn’t care that this will almost certainly produce a proliferation of rapid WMD acquisition. In short, Trump and his crew have made Kissingerian realism—pilloried by the preening foreign-policy moralists of that day—look like a Cub Scout project.

Further Implications of the Sixth Impossible Thing

Is that all? Well, no. Some details need a light dusting. What, for instance, will happen to the Five Eyes, and to intelligence-sharing beyond the Anglosphere? That’s a dead letter. With Tulsi Gabbard now waved into DNI by a compliant Senate, no foreign intelligence service will share anything sensitive with the United States. This is common knowledge already.

Thank you @realDonaldTrump for your unwavering leadership in standing up for the interests of the American people, and peace. What you said is absolutely true: Zelensky has been trying to drag the United States into a nuclear war with Russia/WW3 for years now, and no one has…

— Tulsi Gabbard 🌺 (@TulsiGabbard) February 28, 2025

What is not common knowledge—but ought to be—is that America’s European allies regularly provide the US with intelligence as valuable as anything the US provides to them. The US is very good at helping warfighters, so allies in a fight get more from America than America gets back on balance. But in everyday collections and analysis efforts, America benefits at least as much from intel reciprocation as its allies do. The Norwegians, for example, are in a sweet position to monitor the movement of Russian submarines at Murmansk. Radars in Iceland are excellent intelligence collectors. Fibre-optic cables that run through NATO-Europe eastward are critical to certain kinds of signal-intelligence collection. And all of this is now at risk because America’s allies are understandably worried that Tulsi Gabbard will send a digest of the best stuff straight to Moscow. This is one reason, rarely noted so far, why the Russians are so chipper these days.

What will now become of the fairly extensive US basing infrastructure in NATO countries? Most likely it will diminish and disappear over the next four years—from both ends. The Europeans will not wish to make offset payments to the United States for bases that are no longer linked to credible promises of US protection. Secretary Hegseth, meanwhile, has memoed the heads of all US combat arms services to inform them that they should expect eight percent cuts in their annual budgets for the next four years.

Most US bases and personnel in Europe are not there for Europe’s sake. Beyond their symbolic and tripwire functions, they furnish convenient and relatively inexpensive power-projection capabilities for the Near East and South Asia. But the administration does not seem to want to project its power into those places or even retain the capacity to do so. Wherever George McGovern’s spirit now abides, it must be dancing a jig: His “America, Come Home” plea from 1972 is finally being heeded.

Insofar as Israel is concerned—and a good number of Trump supporters claim to be fond of Israel despite a thick undertow of antisemitism in the MAGA periphery—the administration doesn’t seem to have made the connection between US naval facilities in the Mediterranean and Israeli security. When the guided-missile nuclear submarine USS Georgia—with its 154 Tomahawk Land-Attack Missiles with ranges of 1,600 kilometres, suitable for destroying every Iranian oil terminal structure on Kharg Island—showed up in the Eastern Med some months back to deter the Iranians, it worked. But if the administration closes Rota in Spain and other bases in Europe, the USS Georgia will not be able to show up quickly and stay put for long.

Trump likes to talk tough. But he doesn’t seem to understand that foreign competitors and potential adversaries don’t care about talk, they care about capabilities. “Speak softly and carry a big stick” is excellent advice but most of the time Trump does precisely the opposite. More’s the pity for everyone.

It is important to keep two truths in mind when assessing the significance of recent developments. First, NATO was never just a military alliance. It has always been, at least for its core members, a collective-security arrangement—albeit a lopsided one—with integrated military, economic, diplomatic, and normative dimensions. Donald Trump, zero-sum thinker that he is, has never understood this. Which is why he imagines that funding for NATO is just a kind of protection racket, just another part of his larger delusion that the US government ought to be a profit-making corporation of which he is CEO. He has never understood that allowing some European free-riding did not negate the net value of NATO to the United States.

Second, the extension of a US security umbrella to Europe was never an act of charity. It was the result of a studied conclusion that US national-security interests were best served by preventing European wars that dragged in the United States. NATO was not just about deterring the Soviet Union. It was as much about replacing historical European enmities with new habits of trust and cooperation. By guiding and supporting the creation of the European Union, postwar US policy has accomplished its goal with remarkable success.

That is why those who believe the Europeans are hopelessly squabbling tribes are living in an obsolete reality. Such people like to point out that, from the collapse of the Western Roman Empire until the advent of NATO, at least two—and usually more—centres of power in Europe were eternally at each other’s throats. That much is true. But thanks to US power and perseverance, and the pressure of circumstances, intra-European hostility has finally been laid to rest.

Today, no vestigial European rivalry that does not involve Russia (besides, perhaps, eternal Greco-Turkish enmity) is remotely likely to lead to a shooting war. The historically small Hungary of today, nationalist and autocratic though it is, might some day attack Slovakia to absorb the majority-ethnic Hungarian city of Bratislava (formerly Pressburg). But this is far-fetched so long as the European Union continues to exist. This historical novelty—no enmity great enough to cause a war within Europe and the shared threat of Russia—counsels measured optimism about Europe’s future security capacities.

Some years ago, I contended that the Zeitenwende—a European turning point—was real. I still believe that, and a hitherto glacial process may now accelerate, not least thanks to the results of the 23 February German election. Some defence functions will develop faster than others, and the process will be both affected by and have effects on each country’s domestic politics in ways that are hard to predict.

Of particular significance is that Germany’s postwar liberal-democratic ethos has been inseparable from post-bellicist and pacific security thinking. If Germany must now develop an extensive military industry and possibly even nuclear weapons, what will its postwar compact look like a generation hence?As things stand, Europe needs real leadership above all, and domestic politics in both Germany and France have been dicey in recent months. But the new CDU-SPD coalition under the leadership of Friedrich Merz is more likely to hasten a turning point than any other possible combination.

The Germans need to offload the Schuldenbremse—the obligation to balance annual budgets, first established in 2009 under Angela Merkel. This policy has depressed investment in infrastructure, contributed to the recessionary trends of the past two years, and helped to bring down the Scholz government. The Germans need to understand that higher spending on defence can stimulate their economy, especially the value-added parts the Germans excel at. The sooner it starts, the less time will need to pass for the benign economic and security effects to be felt. At which point, Germany can play its part as a leader in a new European concert.

If the United States really does want to urge and assist the construction of a unitary European security power, it isn’t especially productive to hurl the toddler into the lake yelling, “Swim, you idiot!” Will Europe have the time it needs to find its feet under currently re-wrought circumstances? The answer depends on cases and circumstances and these are complex.

The Sixth Impossible Thing and Russia’s Near Abroad

The US government has been providing useful satellite intel to the Ukrainians via the Starlink and other systems that Europeans cannot presently match. But Europe could match these systems in five years or perhaps as few as two. On the ground, the US has also been providing items the Europeans could not. Nevertheless, Europe has been providing about sixty percent of the Ukrainian order of battle to America’s forty percent. Europe could make up half of that forty percent—so, another twenty percent—in six months to two years.

What about getting Europe’s defence-industrial base integrated enough to produce the major platforms that America has provided? That is harder and will take much longer: most industry estimates fall between eight and ten years. But Swedish accession to NATO may help more than many realise, for the Swedes have managed to produce remarkable scientific-technical and engineering feats with a fairly small population. And if AI enables NATO members to skip a technological generation, the time curve could flatten down to between four and eight years. No one really knows, although that’s clearly much too long to matter in the current war.

All that changes if one looks at a hypothetical post-Ukraine-Belarusisation period, the dangers of which may be fairly modest in narrow military terms given Russia’s manifest military weaknesses, but also extremely politically sensitive. If I were Putin, what might I be thinking of doing next? Well, Russia could attack Latvia, kinetically and otherwise, especially if US tripwire troops are soon withdrawn, as rumours suggest they will be. Why Latvia? Because 35 percent of the population speaks Russian at home (compared to 27 percent in Estonia and five percent in Lithuania), and that’s high enough to tempt Putin’s urge to unite Russia into the “civilisation-state” he likes to talk about.

But invading Latvia would mean war with NATO (or what’s left of it). And if that’s the case, why go small beer? Putin is now 72 and looking at the clock, so he could reason that a new war should be over a strategically more worthy stake. What might that stake be? Connecting Russia’s land borders, perhaps, by pushing through the Suwalki corridor to link up Kaliningrad?

Kaliningrad is currently a vulnerability for Russia. It could be blockaded and choked by NATO-Europe as a pressure point. So it would be appealing, from a Russian military point of view, to eliminate that vulnerability. The map shows that Russian power would erupt out of Belarus, which is entirely under Putin’s control, and soak up either Lithuanian territory to the north or Polish territory to the south—or some of both. Either way, Lithuania’s land access to the rest of NATO to its south would be severed. That would be a big deal, obviously for Lithuania and Poland, but also for Latvia and Estonia to the north—and so therefore to all of NATO-Europe to one degree or another.

So, the farsighted military question to ask is: If the Russians burst toward Suwalki how does NATO-Europe—without the United States and without a US Article V backstop—repel and defeat them? Can they do so?

The answer is yes, probably, depending on when it happens. The longer Putin waits, the more likely and able the Europeans will be to resist and defeat his aggression. But it could get scary; the Russian military might, for example, detonate a tactical nuke high over the Baltic Sea, killing no one but terrifying people throughout Europe. Still, in a Suwalki-corridor scenario, the difference between what the United States has provided to Ukraine and what the Europeans have provided becomes less relevant. Near real-time satellite imagery would be nice to have in a contingency like that, but given the relatively small size of the battle area, air recon and other modalities could substitute well enough for most purposes, assuming European forces can muster the command, control, communications, and intelligence capabilities to enable them to fight together effectively.

On the larger point at issue, there is nothing wrong with wanting to improve relations with Russia, for doing so is in the US grand strategic interest in limiting the sway of Chinese power—even as misdescribed by Secretary Hegseth. But to do so in a way that rewards Russian aggression against a fledgling democratic polity is neither necessary nor in our interest, unless we disavow the value of democracy altogether, which is exactly what many MAGA entrepreneurs and supporters seem to want to do. Some of them really do sound a lot like Carl Schmitt, trying to substitute a mobocracy for a liberal democracy—but instead of doing it in just one country they seem to want to do it in several. This is the Trump version of internationalism.

Specific circumstances matter. Yalta was a tragic but necessary case of spheres-of-influence diplomacy under the circumstances, since the Red Army already occupied eastern and central Europe. We need not repeat that now; there is no Russian army in those territories and the West is much stronger than the Russians as a result of the unity vouchsafed by postwar US policy. A principle-based security strategy has yielded highly practical benefits. As a result, the West—were it to remain in alliance—has options other than a balance-of-power, spheres-of-influence approach to strategy.

In this regard, it is worth remembering that, after the 1939 Soviet aggression against the Baltic States and their absorption into the USSR, the United States never recognised those annexations. Instead, it sat on a block of ice for more than 52 years as a matter of principle. It took the same position with respect to Crimea in 2014. This history needs pointing out, lest some think that rewarding aggression is standard US protocol in the face of a fait accompli emanating from Moscow. It never has been... at least, not until last week. Just as “Swim, you idiot!” is no way to encourage Europeans to put more skin in their own defence, rewarding naked aggression—and looking past all manner of other war crimes, as well—is no way to set up the kind of balance-of-power equilibrium with Russia that the Trump administration claims to want.

Unfortunately, the administration simply does not care about consequences of any shape in Europe, so they have rushed to forfeit a strong position in alliance with Europe for a weaker one without it. And it has done so for what are now revealed to be ideological reasons, or proto-ideological impulses based on motion-driven tics as opposed to actual thoughts. The emotional tics are dark and brutalist, like the kind of unfocussed angst that drives small boys to kill insects with magnifying glasses. The administration has confused complements and opposites. It is a zero-sum approach—besotted, angry, and replete with nihilistic effusions of self-harm projected outward as cruelty.

None of what we have seen in recent days is about strategy or even money. The same destructive shock-nihilism now prevalent in American domestic politics has extruded into the administration’s foreign and national-security policies. It is deep and it is dangerous. Indeed, it reeks of Lord of the Flies.