Cancel Culture

Betraying Their Maverick Roots, Fringe Festivals Have Become Ideological Gatekeepers

A former artistic director of the Nanaimo Fringe Festival describes how transgender activists engineered her ouster.

Growing up in the UK, I became hooked on theatre at a young age. Since then, I’ve come to appreciate live performance not only as an art form, but also as a means to develop empathy among participants—a human quality sorely lacking amid today’s outrage culture.

My first acting role as a child was Violet Beauregarde in a production of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, a role that I won in part because few other children could even half-feign an American accent. Years later, I enrolled in drama at Queen Mary University of London, a three-year half-practical/half-theory program that taught me about theatre’s power to spark social change. During that period, I worked hands-on alongside esteemed practitioner-instructors such as Nadia Davids, whose research focused on theatre’s underground role in South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement. I also gained my first exposure to academic concepts such as Judith Butler’s (seemingly innocuous) notions about the performativity of gender—then-niche philosophical ideas that have since gone mainstream within progressive political culture.

Each summer, the Queen Mary Drama Society took student performances to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe—which is still billed as the world's greatest platform for (and please remember the two words that follow) creative freedom. This renowned festival had been established in 1958 as a response to the growing gate-crashing trend set off by eight uninvited theatre troupes at the (inaugural) 1947 instalment of the Edinburgh International Festival.

Which is to say that the Fringe was conceived as a sort of Salon des Refusés for actors and dramatists. Indeed, the word “fringe” was originally used in its geographical sense, because these performers were literally performing “round the fringe of official [International] Festival drama.”

In 2010, I was fortunate enough to perform at the Fringe alongside some of my peers, a crash course in grass-roots arts administration and promotion that would later serve me well in Canada. I became inspired by the Fringe ethos, and marvelled at this annual mix of aspiring and well-established artists. As an audience member, I loved wandering aimlessly down medieval side streets, often happening upon some incredible yet obscure show being performed in a dingy basement venue, sometimes with audiences of just a few similarly curious souls.

Ten years later, I was approached to produce a small-scale Fringe Festival in the British Columbia community of Nanaimo, where I now raise my two children—a small Vancouver Island town located on the traditional territory of the Snuneymuxw First Nation. Still very much a devotee of the Fringe movement I’d observed back in Scotland, I jumped at the opportunity to champion an open-access arts event that anyone could participate in.

Intent on ensuring diverse participation, I instigated cross-sector partnerships with local organizations, so as to remove financial barriers for immigrant and Indigenous artists through sponsorship initiatives. In my second year as Artistic Managing Producer, I spearheaded free Forum Theatre workshops for Canadian newcomers, which would culminate in a final interactive presentation—an event designed to stimulate community dialogue on contentious issues at a time when Canada, like its southern neighbour, was becoming ravaged by culture wars. Through that work, I have come to meet many Canadians from all sorts of backgrounds, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike—each with valuable perspectives (many being different from my own) and deserving of a platform on which they can express themselves freely.

There are now dozens of Fringe-branded festivals being staged around the world. Indeed, the surest sign of the movement’s mainstream growth is that its acolytes are now overseen by umbrella organizations. These include the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals (CAFF), whose mandate is to “provide mentorship, professional development, and support” to member organizations. Twenty-five years ago, CAFF won a Canadian trademark on the terms “Fringe” and “Fringe Festival.”

In November 2022, CAFF hosted its annual conference in Montreal—the first in-person meeting since I’d begun producing the Nanaimo Fringe. Delegates from across Canada and the United States were in attendance (about a third of CAFF’s membership is American, notwithstanding the organization’s name). Sadly, so too was the political hive-mind that now programs much of the Anglo-American arts establishment.

As a descendant of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society, CAFF once boasted of an edgy approach to art, assuring members that it wanted “no part in vetting the festival’s programme.” Gatekeeping was to be avoided, and censorship was a dirty word—until, that is, the recent imposition of top-down bureaucratic interventions in the name of maintaining a “safe space.”

At the time of its formation in 1990, CAFF required that Fringe Festivals select artists on a non-juried basis (such as a lottery); that Fringe Festivals provide ease of accessibility for all audiences and artists; and that Fringe Festival producers assert no control over the content that artists bring to their performances. At the time, this was (rightly) believed to be a liberal, progressive formula, since it was assumed that attempts at censorship would come from conservatives. Until just a few years ago, no one imagined that progressives themselves would become the primary threat to free artistic speech.

At last year’s Montreal conference, it was made clear that many of today’s Fringe organizers view those principles—especially the renunciation of content control—as “outdated.” In breakout conference sessions dedicated to this topic, it was asserted that “audience safety” was now the paramount consideration. And by this, participants did not mean actual safety, but rather “safety” in the invented sense of being “safe” from exposure to opinions one disagrees with.

A few months earlier, having seen the writing on the wall, I released a public statement on the need to preserve artistic freedom in the Fringe world. But my efforts were in vain. Shortly after the 2022 conference, CAFF deleted a statement on its web site that had read, “Fringe Festival producers have no control over the artistic content of each performance. The artistic freedom of the participants is unrestrained,” downgrading it to “Fringe festival producers do not interfere with artistic content of each performance.” That text sits next to another recent addition: “Festivals will promote and model inclusivity, diversity and multiculturalism.”

In October 2022, Edmonton’s Fringe Theatre, the producer of the city’s annual International Fringe Theatre Festival, cancelled a show by comedian Ben Bankas, on the basis that—according to Fringe Theatre artistic director Murray Utas—“your material may [not] align with our Safer Spaces policy.” The nature of the “material” in question wasn’t specified. But one may assume that the theatre’s objection related to Bankas’ habit of poking fun at gender bending. As for the Safer Spaces policy that Utas cited, it’s an 11-page document that pledges to protect everyone’s “physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual boundaries.”

Wokeness strikes again. My show in Edmonton has been cancelled even though we had almost sold out their venue. Contract was signed January 18th but they are only cancelling March 3rd. Tickets still available https://t.co/r2zuYCtE5N @jordanbpeterson @GadSaad pic.twitter.com/JLSKXBnr51

— Ben Bankas (@BenBankas) March 3, 2023

This is in keeping with developments in Edinburgh, where several Fringe Festival venues recently cancelled comedy performances by five-time BAFTA-winning Father Ted writer Graham Linehan—also on the basis of his irreverence toward the pronoun police.

Reflecting the spirit of the founding fathers of Fringe, however, Linehan responded by setting up his own venue: He performed outside Scotland’s Parliament, from which Nicola Sturgeon had recently resigned as First minister after suffering fallout from her policy of denying sex-based human realities.

Meanwhile, in New York, a work titled Poems on Gender was pulled from that city’s Frigid Fringe Festival after the author, David Lee Morgan, had submitted a blurb that began, “There are two sexes, male and female.”

Remember that the whole Fringe movement was supposed to be about helping and promoting struggling artists who lack the resources of mainstream celebrities. And yet in 2023, the only performers who can face down Fringe’s censors are deep-pocketed figures such as Scottish MP Joanna Cherry, a “gender-critical” lesbian who threatened to sue an Edinburgh Fringe venue that had tried to cancel her performance. (The venue backed down.)

Putting aside the rights and wrongs of the gender debate, cancelling performers on the basis of their views on this issue represents a betrayal of the Fringe movement’s original ethos. This is something I have said publicly—which is why CAFF suspended my festival’s membership in September 2023. In CAFF’s announcement, the organization’s leaders suggested, without naming me, that my views are “transphobic.” CAFF also repeated the canard that airing heterodox views on gender serves to compromise the “safety” of “trans, two-spirit, and non-binary” people.

The controversy, such as it was, began with my sharing of a Guardian article, titled “Trans woman guilty of raping two women remanded in female prison in Scotland,” on my personal Facebook page. Unbeknownst to me, the article had already stoked the flames of outrage among a small but vocal online activist community in Nanaimo.

I then received a direct message from one of the ring-leaders, wishing me misery for my beliefs. Ironically, this was a person whom I’d presented in a virtual show titled Gender Sucks in 2020, as we then operated one of the few Fringe festivals still finding ways to platform artists at the height of the pandemic. (As the expression goes, no good deed goes unpunished.) Incriminating screenshots were attached to complaint letters sent to my organization, as well as to theatre-related Facebook groups in Victoria and Vancouver.

The intimidation tactics used against me reflected a trend identified by Reem Alsalem, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls. In a May 2023 statement, she decried “smear campaigns against women” who speak out for their sex-based rights, which are “intended to instil fear in them, shame them into silence, and incite violence and hatred against them.”

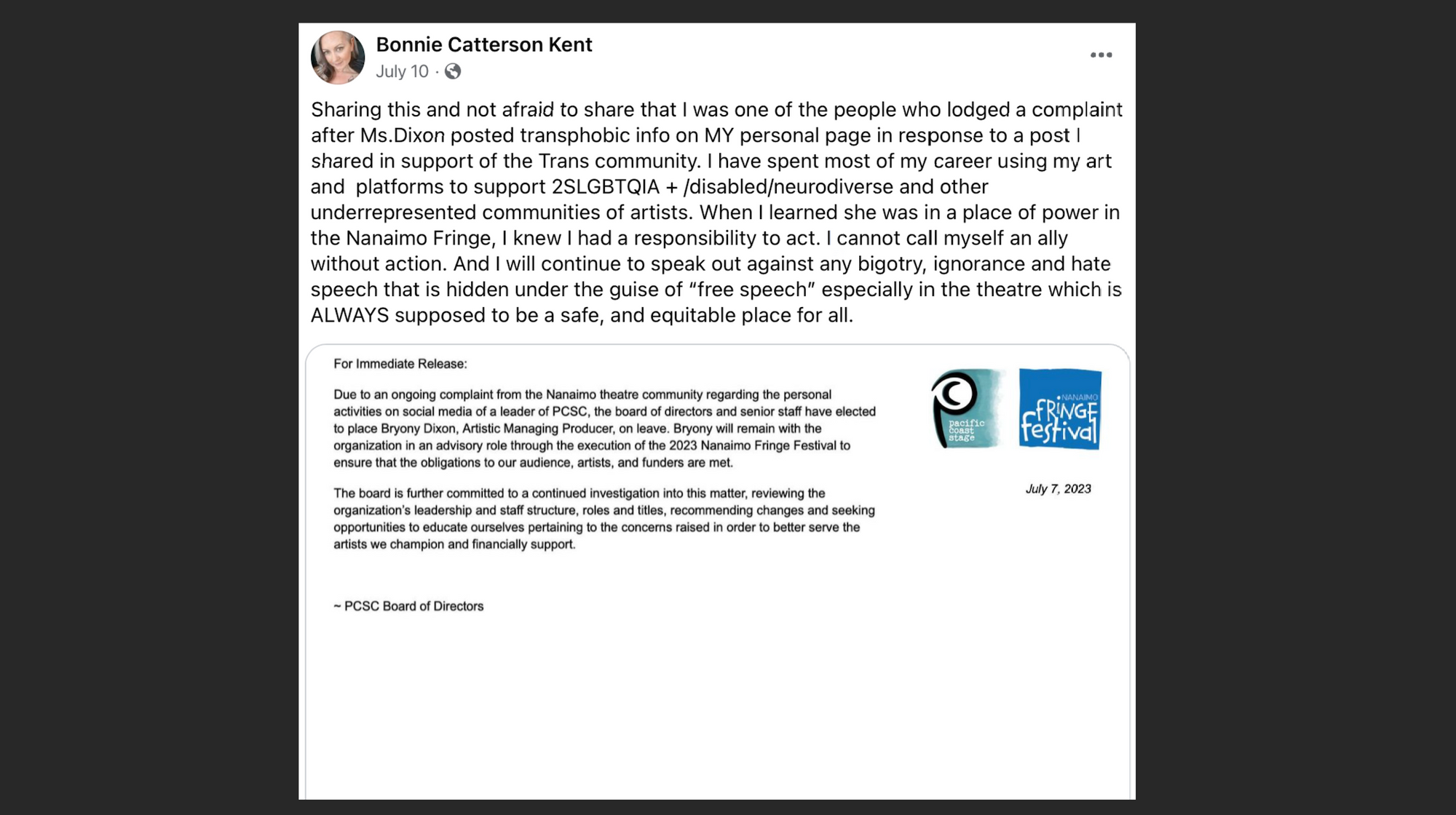

But the campaign against me worked, as I was forced to take a leave of absence from the Nanaimo Fringe Festival. That led to public gloating from my critics. This is what counts as a triumph in their lives: An immigrant single mother losing her livelihood because she believes in artistic freedom, freedom of speech, biological reality, and women’s rights.

I remained involved with the festival in an advisory capacity, to help ensure that the organization could fulfill its obligations to artists, audiences, and funders. I agreed to share operational knowledge and offer mentorship to temporary summer staff so that some dozen theatre artists and groups, 25 stand-up comedians, and four musical acts would not lose their opportunity to perform. But eventually, I stepped aside on a permanent basis. Like most small, not-for-profit organisations, the Nanaimo Fringe Festival doesn’t have the resources to weather a sustained cancellation campaign. And, understandably, few of my colleagues wanted to be targeted by a wave of guilt-by-association smears.

Nothing I’ve done, said, or written, including the contents of this article, should be interpreted as disparagement of any staff, directors, or volunteers involved in presenting the Nanaimo Fringe Festival. Rather, it was always my sincere hope that by demonstrating liberal principles, and assisting to platform those with whom I disagree (some of whom then called for my firing), I could lead by example in times of encroaching group-think.

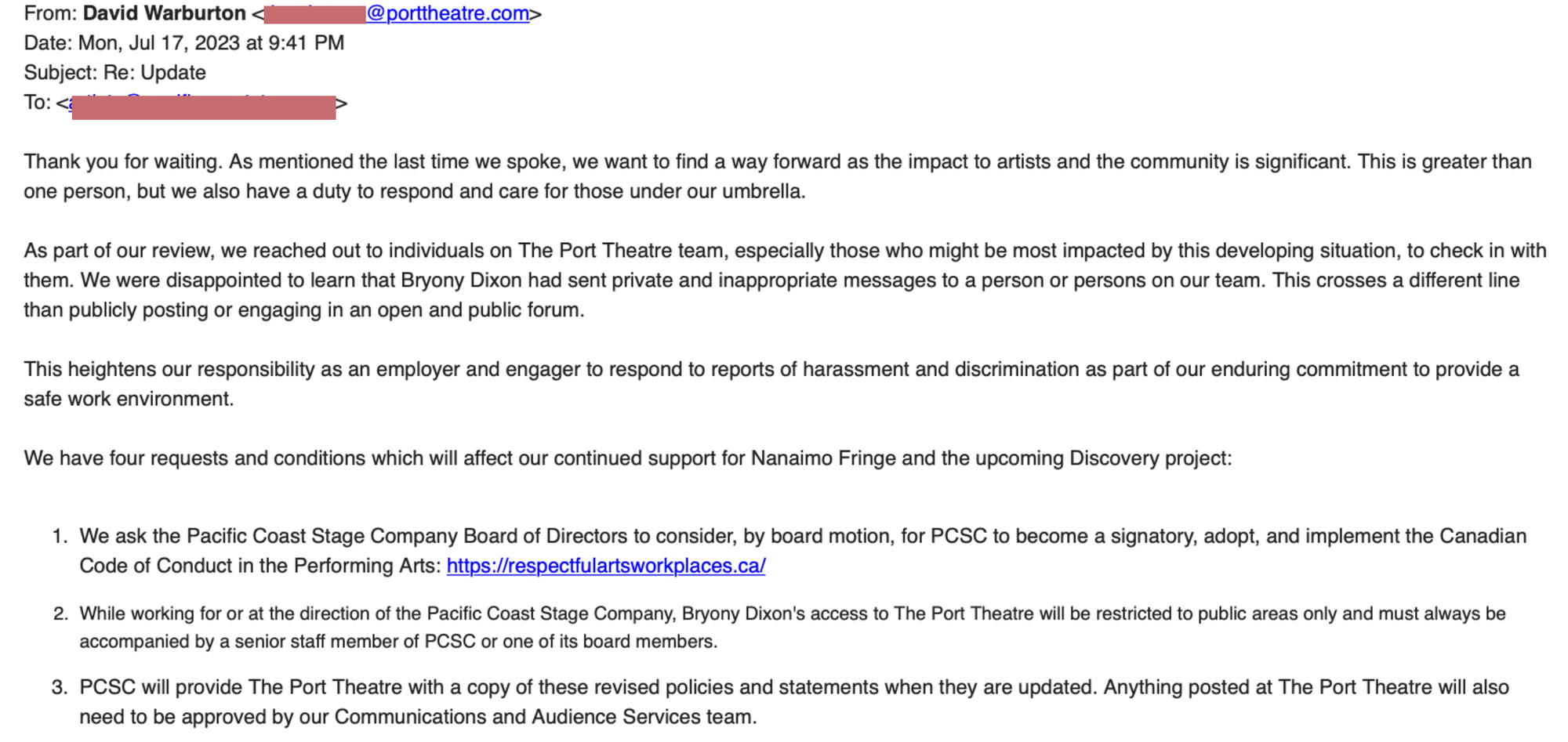

So embittered were my critics that they campaigned to ban me from even attending Fringe Festival events. At one point, the manager of Nanaimo’s Port Theatre even sent a letter demanding that my access to his facility “be restricted to public spaces,” and that, even then, I must “always be accompanied” by a chaperone. What exactly did they think was going to happen if I were permitted to attend a live performance without being tailed by an ideological enforcer?

My presence was also denounced in a closed Town Hall Zoom meeting after the wrap-up of Nanaimo Fringe—a transcript of which was sent to me by mistake. Organizers bemoaned that “she”—meaning me—“was more around the festival than we expected.” It was also said that the artists who’d complained about me were feeling “unheard” because “this person” (again, me) hadn’t been banned outright.

Although I have now resigned from my position, I feel vindicated by recalling the tenacity of the uninvited and unorthodox theatre artists who started the Fringe movement back in 1947. I think they’d all be horrified to see the Fringe name being used by a new set of doctrinaire gatekeepers—bullies who leverage terms such as “safety” and “inclusion” in the same cynical and closed-minded way that conservatives once censored art in the name of protecting public morality.