“I love my nine-year-old son very much but knowing what I know about the future of this planet and the environment he is going to inherit… I have to be honest… if I was making that decision again I’m not sure I would make the same one. I fear for my son’s future.”

These were the words spoken during a debate about the BirthStrike movement at the Battle of Ideas Festival in October 2019. Alistair Currie, Head of Campaigns and Communications for Population Matters and seemingly an otherwise kind and caring father, effectively informed a packed lecture theatre that he wished his son had never been born, and did so while never questioning his role as a virtuous protagonist in this fatalistic narrative.

Disturbingly, this kind of sentiment has now filtered out into a wider cultural malaise of anti-natalism that is increasingly seen as progressive and in humanity’s best interest. Such anti-humanist ideas have become prevalent in modern environmentalism, seized by radical movements such as BirthStrike.

The BirthStrike movement

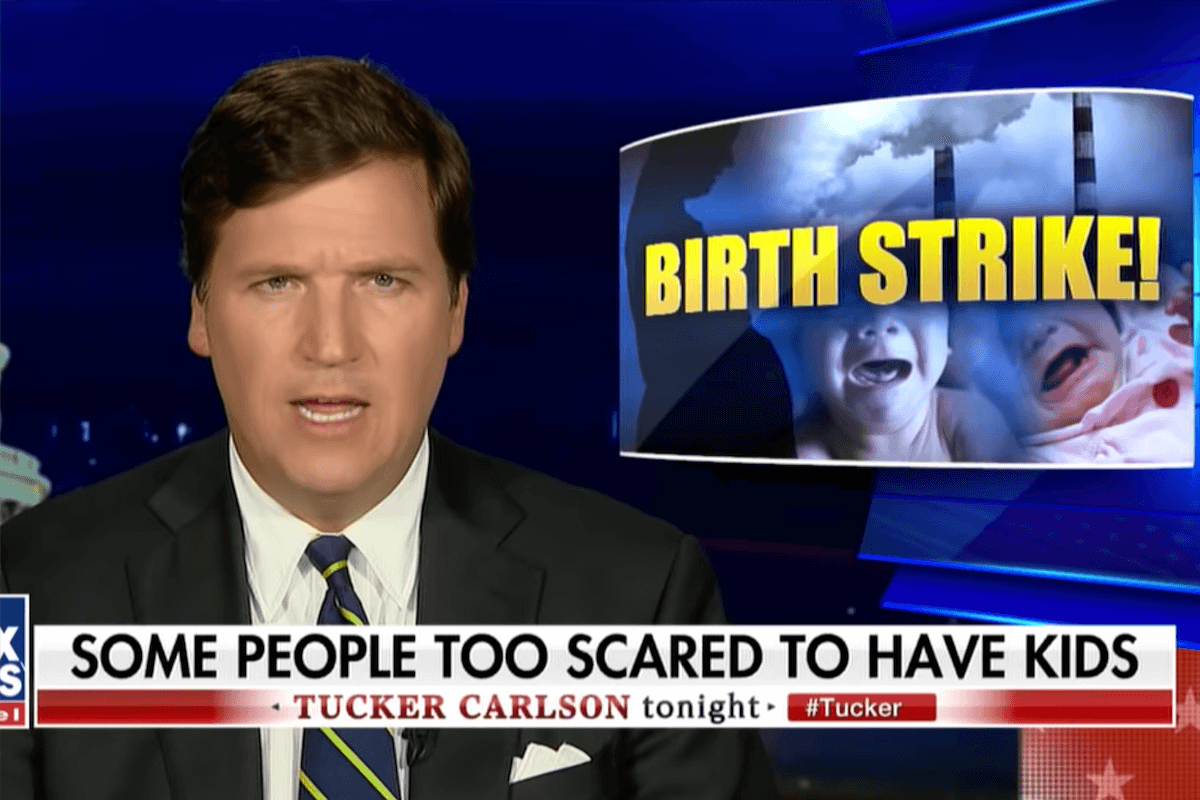

“We feel too afraid to have kids, because we feel that we are heading toward civilisation breakdown,” said Blythe Pepino on Fox News, to a mystified Tucker Carlson. Pepino, singer-songwriter and founder of the social movement BirthStrike, proceeds to explain calmly to Carlson that humanity is faced with two options: either we collectively unite behind action, or consign ourselves to extinction.

Fearing ecological Armageddon, Blythe set up BirthStrike in 2018, an organisation for men and women refusing to have children because of the climate crisis and bureaucratic inertia over dealing with it. Pepino assured Tucker that BirthStrike is different from nihilistic anti-natalism: rather than trying to convert the masses to childlessness, they’re presenting people with a choice. Channeling their “mothering skills into activism,” women can soothe the grief of forgoing motherhood with something “more active and regenerative and hopeful” for humanity.

But, BirthStrikers don’t sound particularly hopeful. “Each day for me is a struggle,” spokeswoman Alice Brown told BBC News. “I’m so depressed and feel so hopeless.” Brown described her climate anxiety as a fear she’d never felt before: an aching dread that “the collapse of civilisation could come from this.”

In 1798, economist and demographer Thomas Malthus predicted a similar catastrophe. He hypothesised that no matter how fast food-production grew, it would always succumb to the exponential growth of the population. Inevitably, he argued, this mechanism results in disaster: famine, war, disease, and the eventual collapse of humankind. His prophecies came to influence paradigms including Social Darwinism, the field of eugenics, and population-control policies like female infanticide. But they proved to be a myopic view of the future.

In spite of population growth, the percentage of the global population living in absolute poverty more than halved between 1800 and 2015, and humanity now faces an epidemic of obesity, not starvation. The fallacy Malthusians commit is to neglect human and technological innovation; the bounds of human ingenuity stretch far further than they imagine.

Yet somehow, modern environmentalists are the latest host of the Malthusian pathogen. “The science is done,” Extinction Rebellion claims, pouring litres of fake blood across Downing Street to represent the death of our children. “We are going to experience hell if this is not sorted.”

Human utility on Earth

The remainder of the Battle of Ideas debate centred around the precariousness of future human life. While it is fair to say that we can do a lot better as custodians of our planet, it seems apparent that any future resolutions to our plight will come from the cumulative knowledge of humanity and exponential upward trajectory of technological advancement. It is not clear that by giving up on the human project we will solve the climate crisis. Where would the world be without, say, the young mind of 26-year-old Boyan Slat, who’s brilliantly ambitious Ocean Cleanup company aims to remove 90 percent of the plastic in the world’s oceans? Who might be born in 2024?

The distinctly modern appeal of BirthStrike

And yet, movements like Birthstrike continue to appeal. While Pepino insists that they are not trying to convince anyone to make their personal choice a political act, BirthStrike does so implicitly by creating a seductive and virtuous identity that taps into unique aspects of modern culture. Activism, environmentalism, and virtue-signaling have never been more in vogue and the BirthStrike identity gives you the trifecta, while saving you a lot of money and personal responsibility along the way.

Identity has rarely been as central to life than it is at the current moment. We are rewarded for our suffering and victimhood, rather than our character and achievements. Someone with no identity-based victim status can therefore adopt one with ease in the form of climate change activism. In the Oppression Olympics, you might not be BAME but you can always be green.

Pepino herself acknowledges that BirthStrike is much more concerned with raising awareness and signaling political allegiance than it is with actually changing population dynamics. Anti-natalist ideas have gained popularity in the West, but it seems unlikely that a global birth strike will gain political traction. Elsewhere in the world, countries are grappling with population decline and labour shortages, with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán trying to offset population shortfalls by offering mothers of at least four children a lifetime exemption from income tax. Meanwhile, countries in Asia are still recovering from dangerous population-control policies like forced sterilisation procedures and female infanticide, with China now facing a shortage of workers who will be able to support its future ageing population. BirthStrike’s zeal thus seems to emerge more from a deep-seated fear of the moral judgement of future generations and final reckoning of our species, than it does from a hard-headed, practical approach to the climate crisis.

As well as an amalgam of social media and virtue-signaling trends, BirthStrike is also a symptom of influencer culture. Evolutionary Psychologist Gad Saad describes this type of ideology as “a parasitic mind virus,” feeding on human susceptibilities such as “prestige influence,” in which we overvalue the opinions of high-status celebrities on issues that aren’t obviously connected to their areas of expertise. Miley Cyrus, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and even the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have all pontificated to the public about their personal choices.

Youthful figureheads like Greta Thunberg are seen as oracle-like in their wisdom, lecturing bodies like the UN on their complacency in the face of the “climate emergency.” Detethered and alienated from older generations, the current generation feels entitled to its disdain on account of its “eco anxiety.” It has a perceived grievance along with the common enemy that every tribe needs. While nihilistic about playing a role in the human project, it is energised by affirming its virtuous identity here at the end of the world. In the minds of these evangelists, the apocalypse really is now, and the pertinent question is one of how future generations will view them. The historic stage is set; all that remains is to cast themselves on the “right” side of it.

The prevalence of anti-motherhood

Despite not trying to convince anyone of anything, BirthStrike continually frames its activism in these Manichaean terms. One is either on the wrong side of history, selfishly prioritising motherhood, or in pursuit of a higher purpose: sacrificing parenthood for activism.

Many BirthStrike members really want children, including Pepino. She often describes meeting her partner, falling in love and being struck with a desire for children—before realising “there was something bigger and more important to do than being a mother,” something more honourable to put her time and resources into. Portraying motherhood in these terms, as irresponsible and time-consuming, is likely to leave some women torn between their natural instincts and the emotional appeal of climate activism.

This way of thinking is not just the preserve of the environmentalists, either. For decades, strains of radical feminism have been convincing women to seek liberation from the “barbaric” nature of pregnancy and the patriarchal constraints of the nuclear family. Children and husbands aside, women are being redirected towards the true embodiment of enlightenment: the 60-hour workweek.

Of course, many women find fulfilment and happiness in remaining childless without fitting the stereotype of the workaholic CEO or radical activist. But the ascendancy of these anti-natalist messages—narratives which inherently place guilt on maternalistic women—may obscure some women’s decisions. “In some ways, it almost feels like the choice is being taken away from me, which makes me quite angry,” a 24-year old student admitted in a video for BirthStrike’s website. While nobody is forced to sign the pledge, BirthStrike makes it obvious which choice it expects women to make by presenting them with the option of playing their part to save the planet, or being complicit in the future apocalypse.

A luxury belief

Is BirthStrike a luxury belief?

Rob Henderson describes luxury beliefs as follows:

[I]deas and opinions that confer status on the rich at little cost, while taking a toll on the lower class… The affluent have decoupled social status from goods, and re-attached it to beliefs… Unfortunately, the luxury beliefs of the upper class often trickle down and are adopted by people lower down the food chain, which means many of these beliefs end up causing social harm.

Does childlessness fall into this category? Something the upper class can afford but which harms the working class? The evolutionary psychology of future discounting as it pertains to life-history strategies describes how the more uncertain the stability of a person’s future environment, the less likely they are to invest in their future planning and the more likely they are to take risks and seek out immediate rewards and gratification. It’s well-documented that marriage is the best route out of poverty—married people are less likely to be poor, sick, in the criminal justice system, etc. Insofar as the Birthstrike movement encourages women not to have children, it will also mean working class women are less likely to get married. In addition, rich, middle-class women with stable futures know that they can just change their minds about BirthStrike later on and have more chance of overcoming fertility issues with expensive IVF treatments or egg-freezing, while poorer women do not have this luxury.

Closing thoughts

Having children is a personal, individual choice, not a collective, political one. Movements like BirthStrike are making a political act out of the most personal thing many people will do in their lives. Whenever the policing of what women do with their bodies happens anywhere—whether legally or culturally—right-minded people usually rail against it. So why is this new age dressing up of an old and repressive idea now seen as progressive?

We must challenge the misanthropic belief that there is something intrinsic to human beings that is the ultimate cause of all our problems. Climate anxiety is just one symptom of the West’s collective nihilism. It is emblematic of a culture that is too exhausted to defend itself, wishes to cease thinking through complicated questions, and yearns instead to be told what to do. We see this in the framing of many topics as “not up for debate” despite there being compelling alternative views. There is an unwillingness to even convince others with rational discussion, with young people making dogmatic pronouncements about “settled” science. We cannot allow climate change to become an alluring identity and faith-based belief system, rather than a rational, reasoned one.