Top Stories

COVID-19 Returns to New Zealand

The outbreak has dented the exemplary record of the New Zealand government in dealing with COVID-19.

On August 9th, headlines in London, Washington, and around the world announced that New Zealand had gone for 100 days without a single case of COVID-19 resulting from a community transmission. There had been a few imported cases discovered during the mandatory 14-day border quarantine period but these were already in isolation. Even so, laudatory headlines were tempered with notes of caution. Looking across the Tasman at the resurgence of the virus in Melbourne, officials and epidemiologists used the milestone to reiterate that people needed to be prepared for further outbreaks. Almost on cue, the streak ended after 102 days, with the discovery of a community transmission in Auckland.

Within hours of the test results, the prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, announced there would be a three-day Level 3 lockdown for Auckland and the rest of New Zealand would revert to Level 2. This was later extended to 14 days. This followed the established government policy of “go hard, go early” in the face of COVID-19 outbreaks. The strategy is to eliminate COVID-19 in New Zealand. There is no talk of “mitigation” or “herd immunity.”

New Zealand has four levels of COVID-19 alert. Level 4 is the most severe. At this level, only essential workers are permitted to go to work and only one person per household is allowed out to shop. Everyone else must stop work or work remotely. People can only leave their homes for exercise locally while maintaining social distance. While this level of restriction is draconian, it did eliminate the virus—at least for a while. In the long run, the government thinks, the best economic response is a strong health response. Better a short sharp shock, followed by a strong perimeter defence at the border, resulting in a return to the relative normality of Level 1 than more lenient alternatives which give you the worst of both worlds: more deaths due to infection and less trade for a protracted period due to people staying home to avoid the risk of exposure to a lethal virus still circulating in the community.

At Level 3, businesses not deemed essential are not permitted to open as usual but are restricted to contactless methods. In practical terms this means you order online and “click and collect” instead of browsing through the shop. If you can work from home, you must do so. Schools close—except for the children of essential workers. Universities close. Lessons and lectures are mostly conducted online instead of in person. People are encouraged to keep their “bubble”—the set of people they come into close contact with—as small as possible. Large gatherings are prohibited. Weddings and funerals can only have 10 guests. As a result of the recent outbreak, the Auckland area, where about one-third of New Zealanders live, was put on Level 3 alert on August 12th.

At Level 2, which applies to the rest of the country, the restrictions are less severe. Shopping remains fairly normal. Even so, at my local supermarket, staff put on face masks once again and the Perspex shields separating queues at the checkouts reappeared. At Level 2 and higher there is a requirement to sign into a public place. It is now compulsory for all premises to display posters with QR codes that can be scanned by the official COVID Tracer app released by the government.

COVID Tracer was launched at the end of May. At that time, New Zealand was at Level 2 alert nationwide, coming down from five weeks at Level 4, followed by three weeks at Level 3. When the app was introduced most businesses had been using manual pen and paper registers to keep track of visitors to their premises as required by the government. On June 8th, after 17 days without a new community transmission, New Zealand entered Level 1. At this level, there was no requirement to sign in and registers disappeared. Life returned to something close to normal. My local football team, the Crusaders, won the cut-down Aotearoa Super Rugby contest in front of a capacity crowd on August 9th.

Just prior to entering Level 1, 522,000 people had downloaded the app. Many places still did not have the QR code posters needed for the app to work. Some were using other commercially developed apps to log visits. During the long period of Level 1 running from June 8th to August 11th, the motivation to install the app dropped off as registers disappeared. However, due to the recent resurgence of community transmissions in Auckland and the fact that the government has now made it compulsory for businesses to display posters of government issued QR codes, the Ministry reported on August 24th that 1,770,000 people had registered using the government app. Of these, over a million had registered since the new outbreak and the imposition of Level 3 alert inside Auckland and a Level 2 alert elsewhere. According to the Ministry, the number of people registered now represents 43 percent of the population over 15 years of age.

The app remains voluntary but the government has orchestrated a state of affairs where not having it is a nuisance at Level 2 and higher. One’s choice at the shops today is to get out your mobile and scan the QR code, which takes a few seconds once you get the hang of the app or you write your name, your address, your phone number, and your email, touching the same surface as everyone else on that register page has done. Obviously, you douse your hand in sanitizer before and after you do this. Once you have done this a few dozen times, downloading the app becomes a compelling alternative.

Presented as a “digital diary,” the app is primarily designed to support human contact tracing. Ministry staff phone those who have come into contact with infected people. Contacts are assessed by interviews not algorithms. Distinctions are made between close contacts (e.g., in households or workplaces) and casual contacts (e.g., in churches or shops). The core functions of the app are simply to keep contact details up to date and to help people keep track of the locations they have visited using QR codes. Businesses are obliged to provide QR code posters and manual registers at their entrances for those without mobiles.

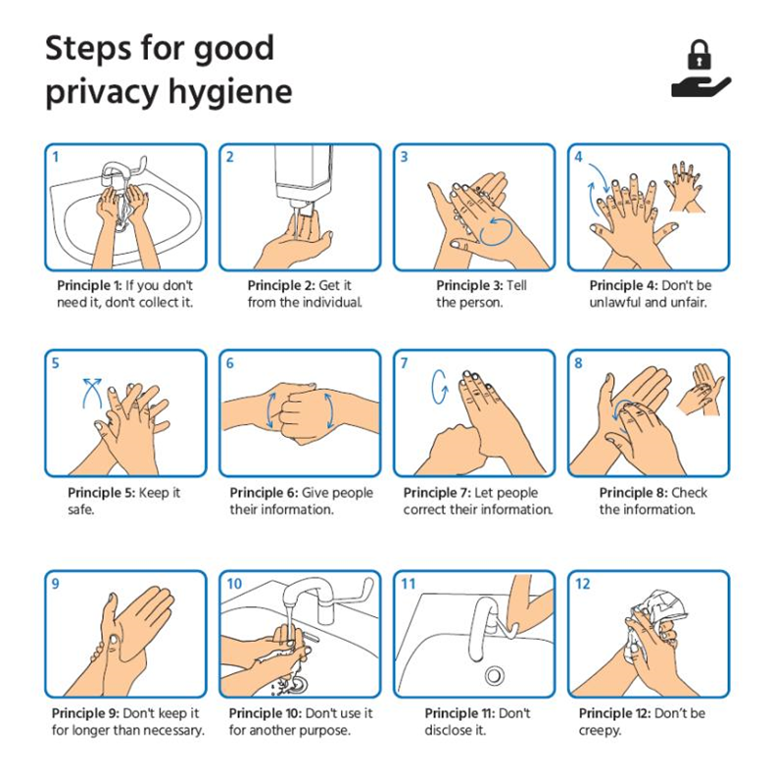

The New Zealand Privacy Commission was consulted on the app design. The infographic below illustrates the Commission’s advice on good practice in handling data generally.

Source: NZ Privacy Commission

COVID Tracer stores data on the user’s handset and works with push notifications. If it turns out an infected person was in the same place as the user, a user who has downloaded the app and opted-in can get an alert on their phone. If an alert is generated on the phone, the user will also get a call from a contact tracer. This can involve the user pushing a button to share their digital diary with the Ministry to facilitate further contact tracing.

Currently, the New Zealand app does not keep track of people via Bluetooth, GPS, or network triangulation. It provides a digital version of pen and ink registers. Obviously, contact tracing is much faster and more reliable when you can search digital diaries rather than retrieve data from paper sitting in filing cabinets across the nation. The app has the modest but vital goal of making contact tracing easier and faster.

While this seems a little cautious from a technical point of view, New Zealand does not yet need a more powerful app. After all, the country went 102 days without a community transmission. The best argument against introducing a mandatory contact tracing app is having no need to do so due to lack of new infections. However, if COVID-19 were as lethal as Ebola and had a shorter incubation period like a typical flu, the case for a mandatory Bluetooth-enabled app would be far stronger.

COVID Tracer might be updated with Bluetooth functionality in the future. However, New Zealand has a cautious approach to the use of algorithms by government. The recently released New Zealand Algorithm Charter requires the limitations of the data to be understood. It is unlikely Bluetooth alone can replace a human in the loop asking detailed questions about contacts. The best it can do is provide a list of people for contact tracers to interview. A Bluetooth enabled “CovidCard” (worn like a normal access card for a secure building) is being tested.

The outbreak has dented the exemplary record of the New Zealand government in dealing with COVID-19. There has been something of a scandal as some border workers have been asking for tests and told not to worry by their managers. It transpires many border workers had not been tested at all prior to the recent outbreak. While they were being asked to report if they had any symptoms, they had not been regularly tested.

A prominent epidemiologist, Professor Sir David Skegg, was scathing in his criticisms of the government when this story broke. He said: “I was really shocked to hear the Director-General of Health say a week or two ago that they were aiming to test people [border workers] every two or three weeks, every two or three weeks frankly would be quite inadequate. But it now turns out that nothing like that was being achieved and I see the reports that more than 60 percent of people working at the border have never been tested.”

He went on to say “weekly testing for frontline staff working at the border should have been compulsory as stringent border protection is vital for New Zealand’s elimination strategy.” To make matters worse for the government, there have been reports of frontline workers wanting tests but their concerns not being addressed by managers.

These revelations put Jacinda Ardern on the back foot politically for the first time in months. Prior to the Auckland outbreak, she was cruising to an easy win in an election scheduled for September 19th. As a result of Auckland moving to Level 3 political campaigning had to stop. The opposition argued that this placed them at an unfair disadvantage, as the prime minister had the ability to campaign from the platform of the daily COVID-19 updates alongside the director-general of health, which are livestreamed and have a large audience, especially when there are new community transmissions being reported. In response, the prime minister decided to delay the election by one month to October 17th.

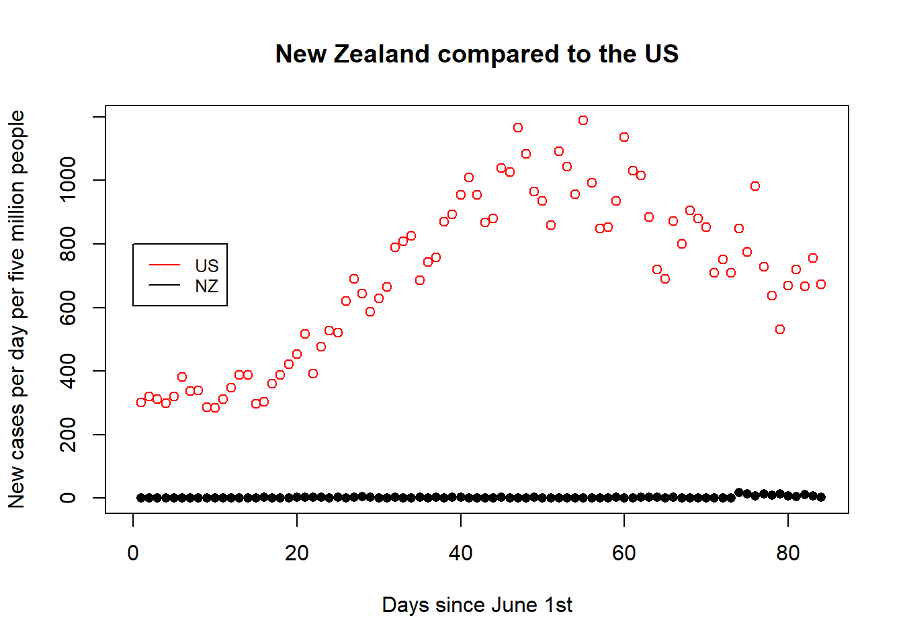

As of August 24th, there were 104 active cases resulting from community transmission since the 102-day streak ended along with 19 imported cases, making 123 in total. As the outbreak appears to have been brought under control it is hard to see Ms Ardern not being re-elected with a clear majority. Looking around the world, it is hard to find democratic countries doing better in terms of eliminating the virus and returning to something approaching normal economic life, without the fear factor associated with the virus still being present in the community. US President Trump’s remarks about the “big surge” in New Zealand have been widely derided. Looking at recent figures it is easy to see why. On a per capita basis, the “surge” in New Zealand is barely a ripple compared to the continuing wave of infections in America.

Source: The author with data from Our World in Data

The government has expressed confidence it has isolated everyone in the Auckland cluster and has decided to end the Level 3 alert for Auckland on Sunday, August 30th. The rest of the country will remain on Level 2. These levels will be reviewed on September 6th. As of Monday, August 31st, the Level 2 alert level will be amended to mandate the wearing of face masks on public transport. This is in response to a recent community transmission on a bus.

While the Auckland outbreak appears to be contained, it only takes one “superspreader” to cause a new one. Levels of infection comparable to those of Melbourne, or another border breach resulting in a new cluster of infections, might yet upset Ardern’s chances of re-election. As things stand though, the public mood in New Zealand is rather like that after a missed tackle that leads to the opposition scoring a try in an All Blacks game. The setback is disappointing, but it is far from a defeat.