Recommended

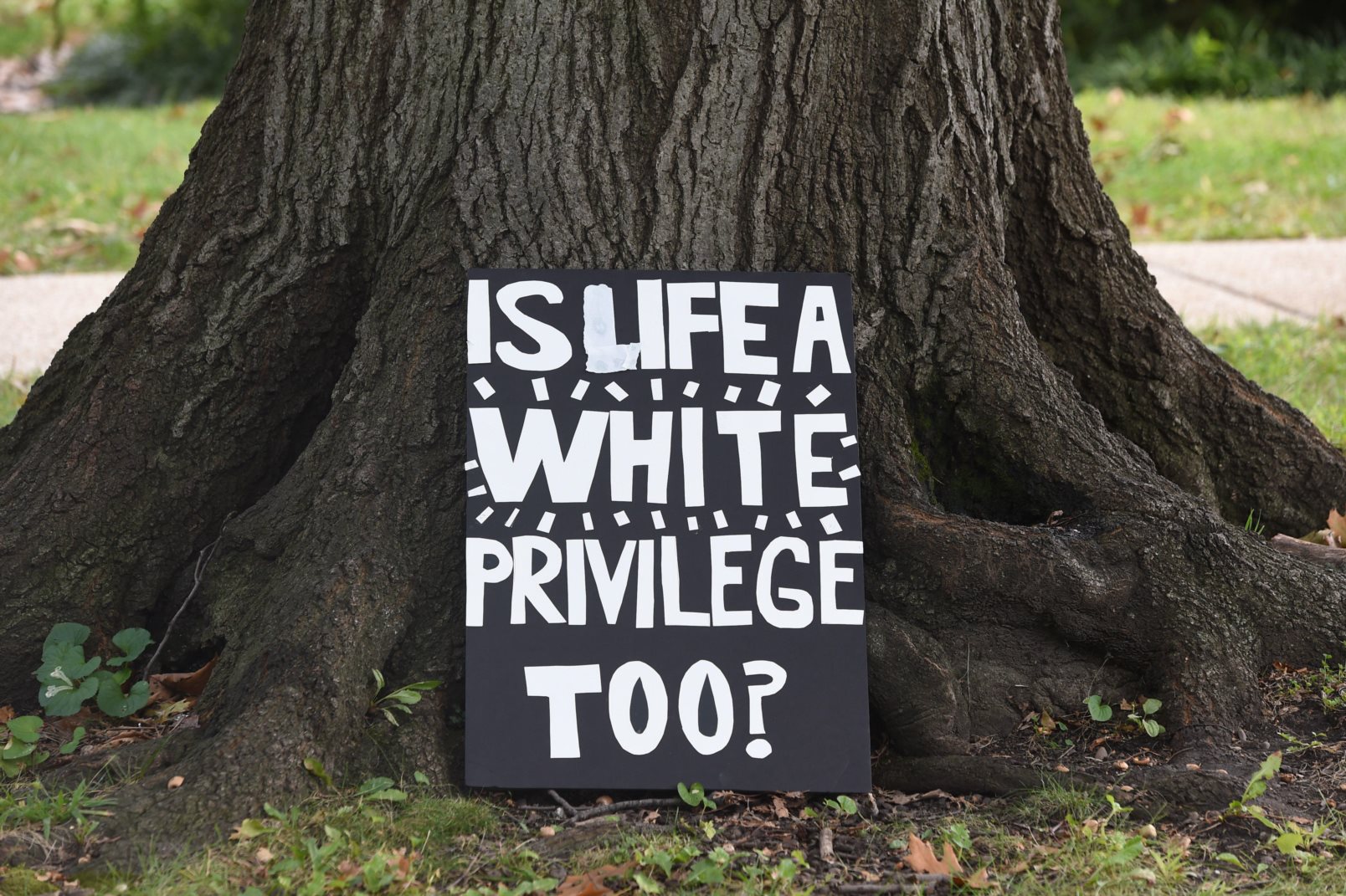

Why White Privilege is Wrong—Part 2

The problem with white privilege is its mono-causal disposition (“one-thing-ism”).

Many people enjoy invoking race as an explanation for all sorts of things. It is a shared pastime for both the far-left and the far-right. The media expend vast sums of money and effort to ensure we don’t escape discussions about race as something that is or should be important. This vocal minority of political extremists and news broadcasters has directed our attention away from more powerful causal explanations that underlie group outcomes. Perverse incentives for these two groups have made race a more a prominent feature of our lives.

As a consequence, white privilege has become the favoured explanation for differences in group outcomes among many educated people. But unintentional or otherwise, by attributing success to white privilege, affluent individuals who invoke this mistaken idea thwart the ambitions of those who are seeking success but who are also lacking in privilege. If we want to not only understand differences in group outcomes but also mend them, then we need a more robust and less ideological framework.

The Pitfalls of One-Thing-ism

The presumption that social groups should be proportionally represented in all activities and institutions is a fallacy that goes against key statistical laws. In nature, there is nothing resembling representatively equal outcomes. Grossly unequal distributions of outcomes are the rule, not the exception.

Here are a few examples. More than 80 percent of the doughnut shops in California are owned by people of Cambodian ancestry. During the 1960s, although the Chinese minority in Malaysia was only 36 percent of the population, they comprised between 80 and 90 percent of all university students in medicine, science, and engineering. In the early twentieth century, Scots made four-fifths of the world’s sugar-processing machinery. In 1937, 91 percent of all grocers’ licenses in Vancouver, Canada, were held by people of Japanese ancestry.

Group disparities often prompt explanations for why these differences exist. Impersonal factors such as crop failures, birth order, geographic settings, technological advances, and demographic differences are all potential explanations. But as economist Thomas Sowell points out, these “morally neutral factors seem to attract far less attention than other causal factors which stir moral outrage.” If something is salient (attention-seizing), then it must be causal. And indeed, discrimination, something we are quick to lock our attention onto, unfailingly serves as a popular explanation for differences in group outcomes.

For the proponents of white privilege, differential group outcomes are a product of nefarious interventionism, past and present. Were it not for those meddling racists, equal outcomes would exist. However, disparities do not imply discrimination. This, in fact, is a classic fallacy known as “affirming the consequent.” Plainly, it means to mistakenly attribute an outcome to a previous event, even though such an outcome could be the result of many other events. Take the true conditional statement, “If it is raining, then the grass is wet.” Upon seeing wet grass, you infer that it is raining. This is an error as the grass could be wet for a number of other reasons. Now take the statement, “If discrimination exists, then differences in outcomes will arise.” This, again, is a true conditional statement. But if differences in outcomes arise, that does not imply that discrimination exists. We easily fall into this trap. All the more when salient factors like race or other physical features are involved.

Still, this does not rule out discrimination as one possible explanation for group outcomes. It is one of many possibilities, each of which must be validated by the evidence. Our emotional responses tell us nothing about the causal weight of different factors.

The problem with white privilege is its mono-causal disposition (“one-thing-ism”). It assumes that discrimination, and only discrimination, can neatly explain the intricacies of group outcomes. This, of course, flies in the face of social science research where many factors, together, best explain a complicated phenomenon.

For instance, Robert Plomin, in his book Blueprint, examines differences in academic achievement among boys and girls. Less than 1 percent of academic achievement can be explained by sex. Put differently, knowing whether a child is a boy or a girl tells you virtually nothing about their grades. But sex is salient, and therefore easy to invoke when people observe differences in outcomes.

Even obvious factors, when taken together, don’t fully explain outcomes. What predicts how well someone does in college? Some might say secondary school grades or SAT scores. Others might say social class is what matters most. However, research indicates that socioeconomic status, high school grades, and standardized test scores combined only account for about 41 percent of the differences in college grades. Granted, 41 percent is a lot by social science standards. But none of these factors come close to fully explaining the differences in academic achievement among college students.

Nevertheless, complex outcomes are best explained by a confluence of factors. In the case of white privilege, there are a number of variables which, when taken together, better explain differences in group outcomes. Here, we share four potential factors: geographic determinism, personal responsibility, family structure, and culture.

Four Explanations for Group Outcomes

In a study of American intergenerational mobility, Harvard’s Raj Chetty made a fascinating discovery: “intergenerational mobility varies substantially across areas within the U.S.” In other words, your odds of doing better than your parents depends in part on where you live. This is what AEI’s Tim Carney calls “geographic determinism.”

Specifically, relative mobility was lowest for children who grew up in the Southeast and highest in the Mountain West and the rural Midwest. For example, “the probability that a child reaches the top quintile of the national income distribution starting from a family in the bottom quintile is 4.4 percent in Charlotte, North Carolina but 12.9 percent in San Jose, California.” Even life expectancy varies. Whereas the average life expectancy in the U.S. was 79.1 years, it ranged from 66 years in the worst counties to 87 years in the best.

Importantly, the black-white upward mobility gap is the smallest in low and high poverty locales. That is, black males who moved to neighbourhoods with less poverty earlier in childhood were more likely to earn more and graduate from college and less likely to be incarcerated than black males that did not. In contrast, black and white males, relative to their parents, were equally poor when living in an impoverished area. This is a particularly important finding as it suggests that differences in group outcomes may be influenced by where people live.

But why do some areas exhibit higher rates of upward mobility than others? For Carney, social capital is the key. Places with more civic activity, regardless of income, have more upward mobility. In fact, Chetty, calculating an area’s “social capital” score, found a strong correlation between civic activity and upward mobility, with religiosity (e.g. going to church) leading the way. Both white working-class and black inner-city neighbourhoods lack the civic institutions that allow for upward mobility. Furthermore, research suggests that a 15% increase in the proportion of people who think others are trustworthy raises income per person by 1%.

The second factor, personal responsibility, refers to individual decision-making. The role of personal responsibility in group outcomes is supported by a much-publicized study by the Brookings Institute. The researchers, Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill, found that to avoid poverty individuals must do three things in order: graduate from high school, work full-time, and not have children outside of marriage. This has come to be known as “the success sequence”. And the statistics supporting it are fascinating.

According to Haskins and Sawhill, individuals in families that adhered to the success sequence had a 98 percent chance of escaping poverty. By contrast, 76 percent of those that did not adhere to any of these norms were poor. In a 2003 analysis of census data, the authors demonstrated that had the poor followed the success sequence, the U.S. poverty rate would have fallen by more than 70 percent. The success sequence affects Canadians, too. A similar study conducted by the Fraser Institute found that 99.1 percent of Canadians who followed the success sequence did not live in poverty. And the pattern remains stable among millennials, as well. According to a study by Wendy Wang and Brad Wilcox, 97 percent of Millennials who followed this sequence did not end up in poverty.

But does personal responsibility help to explain differences in group outcomes? In an analysis of Haskins and Sawhill’s initial study, Brookings Institute researchers found that “blacks and whites who follow the three norms have about the same likelihood of ending up near the middle, with incomes three to five times the federal poverty line.” In fact, Sawhill notes that blacks, despite starting at a lower level than whites, gained far more both absolutely and relatively when following the success sequence, compared to whites. Regardless of racial and ethnic backgrounds, a clear majority of adults who followed the success sequence avoided poverty.

But there is one element of the success sequence that bears closer examination: family structure.

In 1970, the U.S. Census Bureau determined that married parents and their children constituted 40 percent of households. By 2012, that number had fallen to 20 percent. In 1960, 72 percent of adults were married. By 2016, it was 50 percent. According to Pew Research, the share of U.S. children living with an unmarried parent has more than doubled since 1968, jumping from 13 to 32 percent. In fact, almost 40 percent of all babies are now born out of wedlock, with 47 percent and 23 percent of black and Hispanic children being raised by single mothers, respectively. In short, the American family structure has disintegrated, and this weighs heavily upon group outcomes. In general, a child will see the best outcomes in childhood and adulthood if raised by married parents. The social science is remarkably uniform in its conclusions on this matter.

Whereas 8 percent of children born to married parents end up in poverty as adults, 27 percent of children born to unmarried parents live as impoverished adults. According to a study by social scientists Robert Lerman, Joseph Price, and Brad Wilcox, “Youths who grow up with both biological parents earn more income, work more hours each week, and are more likely to be married themselves as adults, compared to children raised in single-parent families.” In fact, a child born to a never-married mother in the bottom fifth of family income is three times more likely to stay in the bottom fifth than a child born to a continuously married mother with an equally low income. To this extent, having stably married parents is worth an extra $40,000 in annual per capita family income.

Furthermore, children raised by single parents not only experience reduced economic gains but face a greater risk of physical harm. Findings on child abuse rates are alarming. Children raised by a single parent are 3 times more likely to be abused compared to children raised by married birth parents. Children raised by a single parent with a live-in partner are 10 times more likely to be abused compared with children raised by married birth parents.

Other research suggests that the costs of child abuse “exceed those of cancer or heart disease…eradicating child abuse in America would reduce the overall rate of depression by more than half, alcoholism by two-thirds, and suicide and IV drug use, and domestic violence by three-quarters.” Single parenthood increases the likelihood of child abuse, and child abuse survivors are less likely to obtain education and employment, and are more likely to experience depression, addiction, and a host of other detrimental outcomes. Therefore, it may be the case that the downsides of single parenthood are even greater than the upsides of intact family structures. As such, it’s not that intact families are so great. It’s that broken families are exceedingly unsafe.

Additionally, research by Lerman and Sawhill suggests that the growth of child poverty from the 1970s to the 1990s was driven, in part, by increases in single-parenthood. Indeed, the current child poverty rate (21.3 percent) would be cut by almost one-quarter had the 1970 rate (12 percent) remained stable. Curiously, several studies have simulated the impact of marriage on poverty rates, “pairing up” single men and women then estimating the effect. One study reported a 43.2 percent increase in the average per capita family income and a 24.7 percent decrease in the child poverty rate. Others report a 43 percent decrease in the black child poverty rate and a 40 percent decrease in the poverty rate among mothers.

Importantly, the economic gap between blacks and whites virtually disappears when we control for family structure. Despite higher rates of poverty among black Americans, the poverty rate among married black Americans has been less than 10 percent in every year since 1994, consistently lower than the white poverty rate. Whereas the Black and White poverty rates were 22 and 11 percent in 2016, respectively, it was 7.5 percent for married blacks. Moreover, one study found that if blacks and whites had the same family structure, the poverty gap would be reduced by more than 70 percent.

Some argue that today’s comparatively weak black family structure is a “legacy” of slavery. This is not supported by the empirical evidence. According to Walter E. Williams, all children in as many as three-fourths of 19th century slave families had the same mother and father. In fact, 85 percent of kin-related black households in New York were two-parent households in 1925 while three-quarters of all black families were intact in Philadelphia in 1880. According to Thomas Sowell, even when blacks were one generation out of slavery, census data revealed a slightly higher percentage of married black adults than married white adults. This fact remained true in every census from 1890 to 1940.

Prior to the 1960s, the difference in marriage rates between black and white males was never greater than 5 percent. Yet, today, that difference is greater than 20 percent.

Fatherlessness lies at the heart of this issue. In 2008, President Obama noted that children who grew up without a father were “five times more likely to live in poverty and commit crime, nine times more likely to drop out of school, and 20 times more likely to end up in prison.” As Warren Farrell and John Gray note in The Boy Crisis, “Depriving a child of his or her dad is depriving a child of part of his or her life.” And indeed, research suggests that fatherless children have telomeres that are 14 percent shorter than that of children with fathers. Shorter telomere length is associated with a shorter lifespan.

Fatherless children have higher rates of suicide, drug abuse, and hypertension. In fact, a staggering 85 percent of young men in prison grew up in fatherless households. This is not at all surprising as every 1 percent increase in fatherlessness in a neighbourhood predicts a 3 percent increase in adolescent violence. Among females, father absence is a remarkably strong predictor of early sexual activity and teen pregnancy. In fact, rates of teenage pregnancy were 7 to 8 times higher among father-absent girls than among father-present girls. This is a particularly important finding as it implicitly touches upon the cyclical nature of fatherlessness. That is, teenage mothers, more likely to come from fatherless households, are more likely to themselves be single mothers.

Then there’s the role of culture. To be clear, culture not only includes customs, values, and attitudes, but also skills and talents that more directly affect economic outcomes. Those with a unique culture often take it with them wherever they live. However, critics of cultural influences have long downplayed the role of culture in the enrichment of once-impoverished immigrant groups. Take Lebanese and Chinese Americans, for example.

When immigration from Lebanon to the United States began in the late 19th century, most of these early immigrants began as street merchants. Once enough money was saved, the Lebanese street merchants would settle down in their own store, open 16 hours a day, with their children stocking shelves and making deliveries. These children, imbibing the shrewdness of operating an independent business on scarce resources, were inculcated with their parents’ work ethic, learning the importance of family unity and delayed gratification. Increasing success in business among Lebanese-Americans afforded their children greater educational opportunities to enter the fields of medicine, law, and science. As such, what mattered was not the little money they arrived with, but the culture of hard work and business acumen the Lebanese brought with them.

Similarly, this pattern of upward mobility is observed among Chinese Americans. Arriving in the U.S. with little more than the clothes on their back, circumstances were such that the suicide rate among Chinese immigrants living in San Francisco was three times the national average. Nevertheless, successive generations of Chinese in the United States have become prosperous through tireless effort. Consider the Brooklyn-based Chinese who immigrated from the Fujian province. According to Kay Hymowitz, the Fujianese “crammed themselves into dorm-like quarters, working brutally long hours waiting tables, washing dishes, and cleaning hotel rooms—and sending their Chinese-speaking children to the city’s elite public schools and on to various universities.” In fact, it is often said that the first English word the Fujianese learn is “Harvard.”

In general, this culture of determination and sacrifice has paid dividends for Chinese Americans not only economically but socially. According to Amy Chua and Jed Rubenfeld, Asian American teenagers—and Asian Americans on the whole —have dramatically lower rates of drug use and heavy drinking than any other racial group in the United States. Moreover, Asian American girls have by far the lowest rates of teenage childbirth of any racial group, with 11 births per thousand in 2010, as compared to 24 for whites.

Attitudes to work differ among groups in the same society. In White Liberals and Black Rednecks, Thomas Sowell details the lack of a work ethic among American antebellum Southern whites. Relative to German immigrants who painstakingly dug up trees by their roots when clearing the land for farming, Southern whites simply cut the tree down and ploughed around the stump. There were similar contrasts in the production of dairy products. Whereas the South had 40 percent of dairy cows in the U.S. in 1860, they produced just 20 percent of butter and only one percent of cheese. This demonstrates how cultural values affect outcomes within members of the same racial group. Consider differences in group outcomes among native and foreign-born blacks.

Despite New York being the principal destination of blacks from the Caribbean, this group is outnumbered by a factor of four by native-born American blacks. Nevertheless, the first black borough presidents of Manhattan were West Indians. As late as 1970, the highest-ranking blacks in New York’s police department were West Indians, as were all the black federal judges in the city. 1970 census data showed that black West Indian families in the New York metropolitan area had 28 percent higher incomes than the families of American blacks. Furthermore, the incomes of second-generation West Indian black families living in the same area exceeded that of black families by 58 percent. Studies published in 2004 revealed that an absolute majority of black college alumni were West Indian or African immigrants, or the children of these immigrants.

Neither race nor racism can explain these differences. Nor can slavery, because West Indian blacks, like native-born blacks, have also experienced a history of slavery. A more plausible explanation is culture. A study of West Indian blacks in the United States noted that they possessed a zest for learning that surpassed native-born Americans of any race.

Culture matters. Researchers, David Austen-Smith and Roland G. Fryer, Jr., note that “black peers and communities impose costs on their members who try to ‘act white’.” To this extent, Fryer and Torelli, using two nationally representative datasets, found that blacks were more likely to associate good grades with unpopularity. In fact, the researchers estimated that eliminating the difference between blacks and whites on their views on grades and popularity would reduce the black-white test score gap by 10 percent, effort gap by 40 percent, and homework completion gap by 60 percent.

Tying It All Together

Geographic determinism, personal responsibility, family structure, and culture work in tandem to explain differences in outcomes. Recall Raj Chetty, whose research found a correlation between neighbourhoods and economic mobility. His study turned up only one other local characteristic that rivalled social capital in boosting social mobility: two-parent households. However, it isn’t enough just to live in a two-parent household. If you grow up amid intact families, the American Dream is alive and well. Indeed, the proliferation of intact families in a neighbourhood serves to increase social capital.

Furthermore, the social capital which underpins geographic determinism is ultimately a consequence of the culture of a neighbourhood. These values influence the decisions made by those living in the neighbourhood. These decisions then feed into family structure, ultimately reinforcing the neighbourhood’s culture while preserving social capital.

All of this is to say, each of these factors are connected. On their own, they can only explain part of why group outcomes differ. But together, they paint a clearer picture than the one drawn by the adherents of white privilege.

These factors are less thrilling than blaming a specific racial group. If we want to feel the satisfaction of directing blame while enhancing in-group solidarity, then invoking white privilege is not a bad strategy. “White privilege” gives you a simple answer and a clear enemy. But if we truly want to understand and mitigate group differences, then taking a closer look at the data is a far better approach.