Conformism

Conformity: The Power of Social Influences—A Review

We are natural conformers because, more often than not, it keeps us alive and in good standing with our peers.

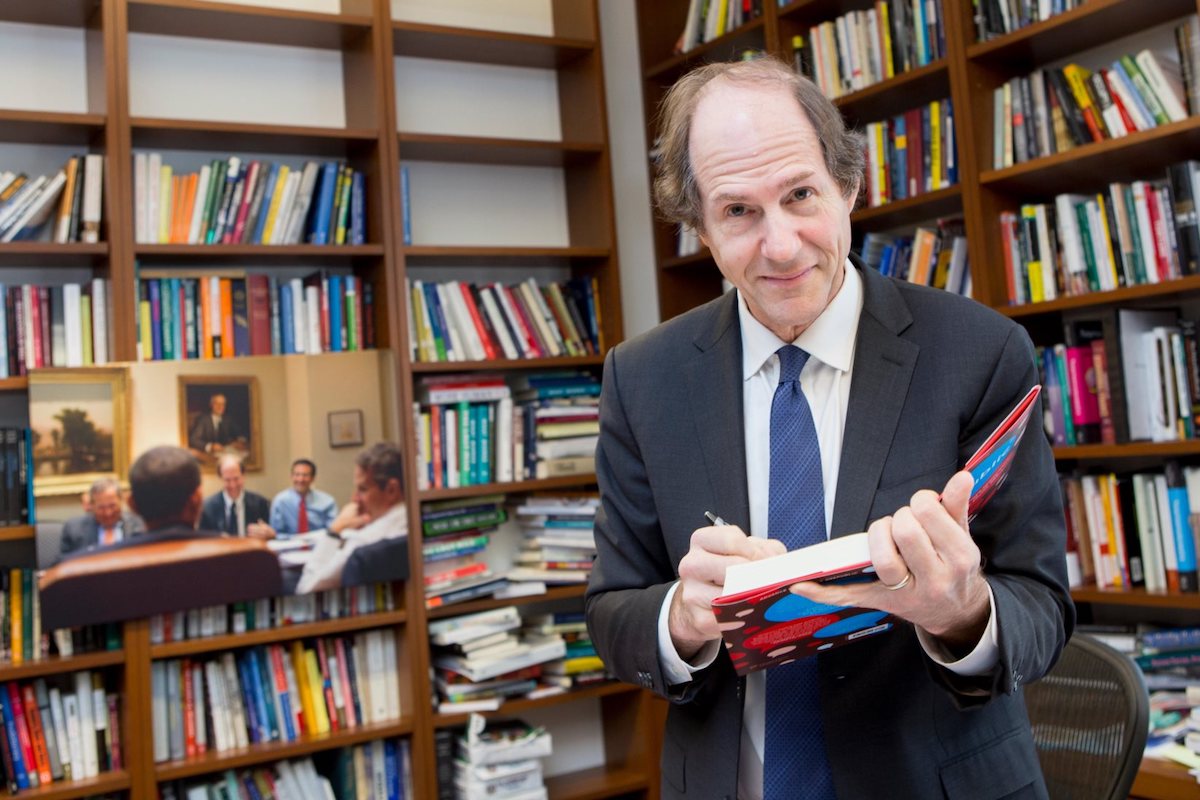

A review of Conformity: The Power of Social Influences by Cass Sunstein, NYU Press, 176 pages (May, 2019)

“It’s often a good idea to adopt the practices and beliefs of the people around you. For one thing, the people around you aren’t dead. If you do what they do, you might continue not being dead as well.”

-Steve Stewart-Williams

You’re sitting at a machine. A serious-looking experimenter holds a clipboard nearby. In another room, there is a man with electrodes attached to his arms. You ask questions, the man responds. For each incorrect answer he gives, you press a switch, delivering what you believe are increasingly higher voltage electric shocks. The man cries out in pain, shouting about his heart condition. You express concern, but the experimenter tells you to continue the experiment.

You have probably heard of this well-known study as the Milgram Experiment. Prior to the study, Stanley Milgram had asked 40 psychiatrists to estimate how many participants they thought would continue to the end of the experiment, delivering the final 450-volt shock. Their estimate was one-tenth of one percent. They thought nearly everyone would be so disturbed they’d stop the study. In reality, 65 percent of participants pressed the final switch.

In another version of the study, Milgram added a twist. He hired two confederates (actors) to join, along with the participants. For each trial, there was a team of three people: the participant and two confederates. Milgram secretly instructed the two actors to dissent, refusing to administer shocks beyond a certain point. To his surprise, when the confederates refused to continue the shocks, over 90 percent of participants went along with them. They joined in rebelling against the experimenter, ignoring his calls for further shocks.

Our urge to obey authority is powerful. But our drive to conform is greater.

Cass Sunstein’s new book, Conformity: The Power of Social Influences, delivers a brisk and accessible overview of research from social psychology, economics, and political science on how people behave in groups. Sunstein, a Harvard professor and alumnus of the Obama Administration, discusses the dangers of conformity and ideological groupthink in structuring a society and its various institutions. Sunstein, moreover, examines how viewpoint diversity can serve as a bulwark against group polarization and institutional rot. Indeed, any organization, system, or society which does not incentivize freedom of expression and public dissent is one that is doomed to fail.

Commitment Issues

If you’ve seen the film Men in Black, you’ll remember the now iconic quote delivered by Agent K, played by Tommy Lee Jones. When challenged on the intelligence of humans, K replies, “A person is smart. People are dumb, panicky, dangerous animals and you know it.” There is something about this line that rings true. K’s words are accurate not because they expose the fallibility of human intelligence, but because they reveal a quirk in the human condition: we become different people in groups. In many ways, this quote captures the theme of Sunstein’s book, albeit in a blunt and unrefined manner.

For many people, conformity sparks mental images of sheep doing what they’re told. But in fact, at the outset, Sunstein notes that conformity has its advantages. We lack information about science, health, politics, and so on. Not only that, but we simply don’t have the time to assess every option presented before us. Oftentimes, the most rational course of action is to follow the choices of those we trust. We are natural conformers because, more often than not, it keeps us alive and in good standing with our peers. But sometimes it can lead us to disaster.

Consider group polarization, the topic of one of the chapters. In short, social psychologists have found that when individuals hold certain beliefs, those beliefs are magnified when they interact with others who hold similar beliefs. In a study on jury behavior, researchers gave jurors an 8-point scale to measure how severely they wanted to punish a law-breaker. They found that when individual jurists preferred high punishment, the overall verdict ended up higher than that recommended by the median juror. Put differently, when individual jurors preferred a severe punishment, deliberation with other jurors sharing this view raised the overall severity of the punishment. One juror might say they want to impose a fine of $10,000 while another might say that anything less than $12,000 is unacceptable. By the end, the fine might increase to an amount far beyond anyone’s initial starting point. On the flip side, Sunstein reports that groups comprised of lenient jurors produced even more lenient verdicts than the one recommended by the median juror in the group. When group members drift in a certain direction, individual members will double down on that perspective to show their commitment. This drives the group towards extremism despite individual members not being extremists themselves.

For Sunstein, deliberation among the likeminded creates an ideological echo chamber where moderately held beliefs become dogma. To this extent, Sunstein notes that groups act as affect multipliers. They increase the credibility and acceptability of certain ideas held by those in the group. Consider outrage culture. In the age of social media, individuals initially outraged when confronted with an act of moral wrongdoing become even more outraged after consulting with their respective group.

In some cases, group polarization occurs because of “rhetorical advantages”. Sunstein shares a study in which law students tended to support higher punitive awards for those suing corporations. By Sunstein’s reckoning, it is easy to come up with arguments for why corporations should be severely punished. Alternatively, leniency for corporations is unpopular. Thus, those who advocate for stricter punishments have the advantage. Relatedly, psychologist Paul Bloom, in Against Empathy, has suggested that there is a rhetorical advantage for those who prize empathy over free speech. As he puts it, “free speech is always on the side of the censor. It is easy to feel the pain of the person upset by speech…the case for free speech, in contrast, is pretty unemphatic.” If someone is hurt by what another person says, those who come to their aid hold a rhetorical advantage over those who argue for the abstract principle of free speech. You look kind when comforting a hurt person and you look like a jerk when prioritizing the value of free expression over hurt feelings.

The Conformity Paradox

Then there are what Sunstein calls “affective ties.” Plainly, dissent can disrupt social harmony, which is not always the best course of action when interacting with our peers. As the book puts it, “Some forms of dissent might correct mistakes while also weakening social bonds.” This can be risky. The choice we face is a difficult one. Do we share our views, introducing information that could improve group decision-making, or do we go along to get along, preserving our social relationships in the process? When we are bonded by affective ties, the latter option is often more appealing. But for Sunstein, the first option offers indisputable long-term benefits.

The problem with conformity is that it deprives a society of the information it desperately needs. Sunstein rightly asserts that conformists are often viewed as protectors of the social interest while dissenters are seen as selfish individualists, calling attention to themselves and disrupting the status quo. This is not always the case. The dissenter challenges the status quo, introducing new ideas that may aid his group by improving an ailing system. The conformist is reticent, choosing to live in comfort as his group blunders.

Consider the war-making capacities of the Axis and Allied powers during the Second World War. Sunstein, citing the observations of political scientist Luther Gulick, contends that the systems of review and criticism that were embedded in Allied democracies allowed them to triumph over Axis autocracies where dissent meant death. Free expression gave the Allies a key advantage. For Sunstein, institutions perform better when citizens do not stifle themselves and information can flow freely. Indeed, orthodoxies form when there is no pushback. This highlights the importance of free speech as a tool for encouraging dissent; for pointing out that the emperor has no clothes.

However, when people hear what their group members believe, they are motivated to reflect those beliefs back in order to preserve their position. In a group where individuals are motivated by, say, truth, individuals can afford to ignore feelings. But sometimes truth isn’t the goal of groups.

Dissenting can sour others’ feelings toward you. In a group where the aim is to make good decisions, stirring those feelings might not be a big deal. But if the aim, explicitly or implicitly, is to promote cooperation and harmony, dissent can lower your standing within the group. This is especially the case if you are close to those in your group. This is the conformity paradox. The more you care about the people in your group, the stronger the social incentive to be dishonest with them.

Beware of Cascades

In another chapter, Sunstein draws heavily on his work with famed economist Timur Kuran, the scholar who coined the term “preference falsification”. Here, Sunstein introduces two very important concepts: informational cascade and reputational cascade. These concepts, when put together, help us understand how seemingly bad ideas come to be accepted by large swathes of a population.

Informational cascade refers to a process by which individuals stop relying on private information or opinions, sticking only to what is publicly known. This lack of information about what individuals privately think allows other bits of information to be prioritized and to become engrained within the public conscience. After all, if you’re never introduced to the notion that the world is round, you’ll continue believing the world is flat because that’s what everyone else believes. Informational cascades are particularly dangerous as people might converge on an idea that is erroneous.

Reputational cascades follow the same internal logic except that private information is withheld not because people don’t know any better but because they are afraid that sharing it might damage their reputation. Indeed, in an environment where an orthodoxy exists, it may be risky to go up against certain ideas.

When we put the informational and reputational cascades together, it becomes easy to see how certain ideas come to nestle themselves in the public conscience. If people are unaware of an alternative viewpoint or too scared to share it, then orthodoxy cannot be dislodged.

Old Studies and Affirmative Action

Though a very good book, Conformity is not without its flaws. Sunstein leans heavily on a number of old studies. Much of the social science literature has been updated, and it would have been useful to see how recent work could be practically applied. Still, the principles Sunstein discusses are reliable. Fortunately, he reports classic findings on a topic that has survived the recent replication crisis. For better or worse, research on obedience, polarization, and group identification is robust. It is now beyond doubt that people conform with their groups, punish norm violators, identify with in-groups, and denigrate out-groups.

Furthermore, there is one sub-section in chapter 4 that seems out of place. Though Sunstein’s policy recommendations are perspicacious, his defense of race-based affirmative action as a tool for improving viewpoint diversity on college campuses is not well explained. To specify, Sunstein states, “The simple idea here is that racially diverse populations are likely to increase the range of thoughts and perspectives and to reduce the risk of conformity, cascades, and polarization associated with group influences.” While it is certainly true that minority groups can contribute unique experiences to a discussion, it is unclear how this policy would improve the current climate of political correctness on college campuses. Indeed, many American colleges that already practice affirmative action are currently awash with self-censorship and ideological groupthink. It is possible that affirmative action increases viewpoint diversity, but Sunstein does not discuss how the current trend on university campuses relates to this claim.

Perhaps the reason for Sunstein’s support for affirmative action lies in his support for ideological diversity among judges. Sunstein reports that intellectually independent judges were more likely to engage in whistleblowing, eschewing conformity for the sake of truth and justice. However, Sunstein is conflating the ideological diversity of circuit court judges with the racial diversity of college students. These things are not the same. Sunstein himself states, “what matters is diversity of ideas, not racial diversity.” If this is the case, why not just advocate for affirmative action based on ideological diversity, or at the very least, a college application process that includes viewpoint diversity? Furthermore, the supposed merits of affirmative action must be reconciled with the evidence (for example, see here, here, and here) suggesting deleterious effects on students.

In this tightly written book, Sunstein reviews key findings from classic studies in social psychology, economics, and political science to describe how the decision-making process works, depending on whether groups and individuals prize outcomes or reputation, and provides an excellent examination of the benefits and dangers of conformity, as well as the underlying mechanisms behind it.