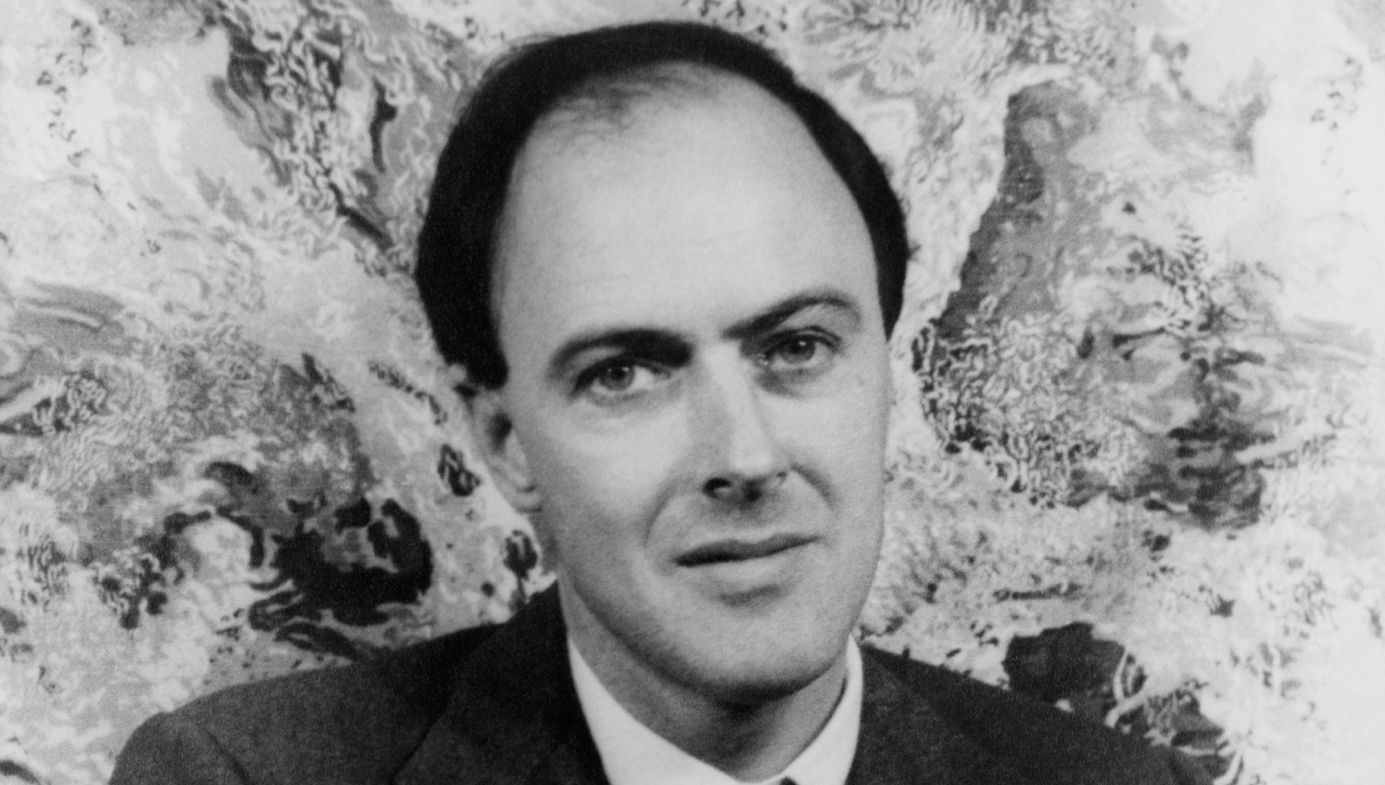

Books

From To Kill A Mockingbird to Ballet Shoes: A Plea to Save Children’s Literature

Reading is a gateway to empathy and understanding.

The Peel District School Board straddles the outskirts of the Greater Toronto Area, with more than 150,000 students enrolled in its elementary and secondary schools. Visible minorities make up more than half of this culturally and linguistically rich catchment area. And occasionally, local controversy erupts when the progressive mandate of the provincially-run education system accelerates headlong into the more conservative attitudes of local parents, especially when it comes to sex education. Indeed, Ontario Premier Doug Ford campaigned successfully on a promise to roll back the most progressive elements of the curriculum put in place by the previous (Liberal) government.

But the problem runs deeper than discussions of birth control and safe sex: A recent Peel District controversy over Harper Lee’s classic 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird shows how wide this gulf has grown between ordinary parents and the professional class that presumes to oversee the educational system.

“To Kill a Mockingbird may only be taught in Peel secondary schools, beginning this school year, if instruction occurs through a critical, anti-oppression lens,” declared the School Board in a recent memo. “When To Kill a Mockingbird is taught outside of this context, the novel has the potential to cause hurt and harm. As educators, we have an obligation to provide learning environments that are safe and inclusive—that honour staff and students’ identities, cultures and lived experiences, including those of the Black community. Of this, there can be no debate.”

To be fair, To Kill A Mockingbird is a bit of a tired chestnut. This isn’t the first time that the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel has become a prop in the battle over political correctness. But the language used by the School Board—especially the jargonny reference to “a critical, anti-oppression lens” and the stark denunciation of “debate”—really does betray how little concern many educators have for the viewpoints of ordinary students and parents, most of whom would prefer that children read and appreciate a gripping and iconic morality tale than be subjected to turgid lectures cribbed from critical-race-studies texts.

The episode is symptomatic of a phenomenon I have observed as a schoolteacher elsewhere in Canada and beyond: The children’s literary canon is sinking into the muck of identity politics, with grievance-studies devotees seeking to either “de-platform” older books, or teach them through the single-issue lens of grievances studies.

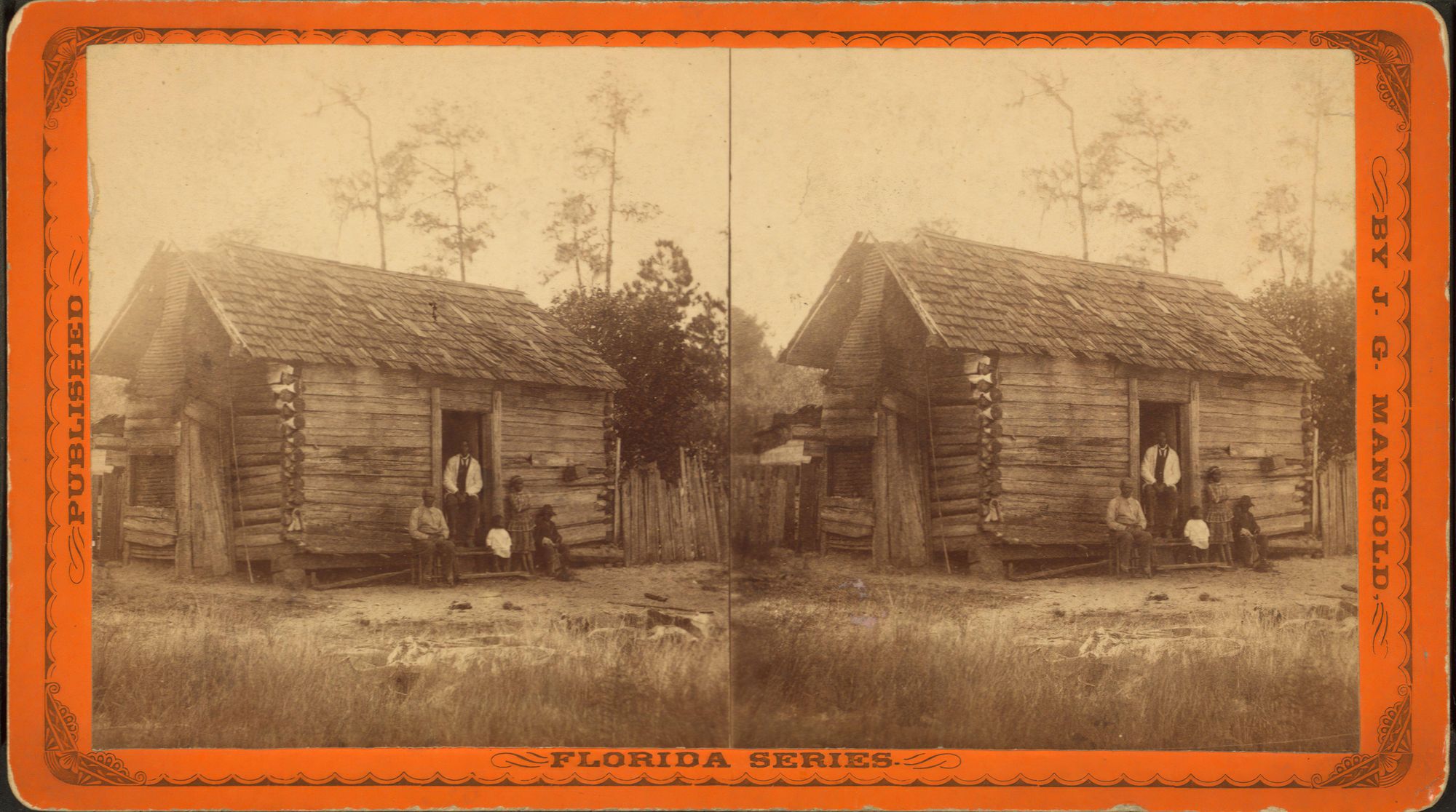

One can see how these forces coalesce institutionally—often with good intentions, at least at first—through the minutes of a June 2018 Peel District School Board meeting, which featured discussion of We Rise Together (WRT), a group that was formed with Board funding to investigate and challenge systemic racism against black students. Out of that meeting came the demand “for changes in learning material that portrays black people in a negative context, to remove To Kill a Mocking Bird [from] the reading list, to have educators offer positive and encouraging comments to black students in classrooms,” and so on. The minutes specify that “A response will be brought to the next Regular Meeting of the Board.” And the times being what they are, it was evidently difficult for the Board to resist falling in line.

Minutes from a WRT Advisory Council meeting in April, 2018 shows how the process works at a granular level. WRT workshop participants, we are told, expressed a fervent desire for more materials and training about combatting racism (which seems credible, since, in the current environment, few educators would attend such a meeting and not feel inclined to publicly strike such a posture in front of their peers). We also are informed that “there is hunger amongst the White administrators to bring the information back to their home schools and to work in school teams within their local team context…If White teachers are concerned about going back to their White colleagues to tell them about what they are learning, what does this say? That we have a problem of White supremacy.”

Plow through these documents, as I have, and you will find that the ideal teacher is held up as the constantly on-message teacher-activist who has memorized a list of fashionable terms and aphorisms, and who labors tirelessly to proselytize colleagues in regard to these approved mantras. In a January 2017, Peel Board Meeting, for instance, Director of Education Tony Pontes gushed appreciatively about a colleague who’d done work “to help students succeed, such as equity and inclusion, providing gender-neutral washrooms, acknowledgement of First Nations lands, student census, and support for black boys.” As for the three R’s, well, there’s only so much time in the day.

In a recent Toronto Star column Rosie DiManno quotes some of the anonymous responses she received from educators about the To Kill a Mockingbird controversy, including this one: “What next, The Merchant of Venice because Shylock is a Jewish moneylender without remorse. Maybe they’ll decide Shakespeare isn’t appropriate for this age. Is this the first shot across the bow to see how much pushback they get?’’ Alas, this proved prophetic. Not so long after these words appeared, the leader of Bishop Strachan (BSS), a private Toronto girl’s school in Toronto, had to surrender her own pound of professional flesh after an English theatre company performed a satirically adapted, performance-art version of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice for BSS students. Principal Judith Carlisle’s last position had been head teacher at Oxford High School in England, where the same play had been staged, by the same company, without incident. At BSS, the reaction was very different. Carlisle resigned. Alumni were informed by email that “the process [of staging the play] failed to adequately prepare the students or provide appropriate context which exacerbated the damage, a reality for which we are deeply sorry. In hindsight, it was an error. An internal review is underway to establish guidelines and procedures to ensure this will not happen again.”

Such controversies aren’t new, of course: Every generation worries that modern students aren’t learning the beloved classics of their own childhood. And every cohort of educator should be alive to the possibility that the classics of yesteryear might need to be supplemented, or even replaced, by new books. But the use of social media as a tool of activism has turbocharged this process, with schools now stepping over one another in an effort to show how committed they are to ensuring that every single assigned book can be justified by direct reference to modern sensibilities. One private boys school in Toronto with which I am familiar, for instance, recently assigned its Grade 6 students the following books: Refugee by Alan Gratz (examination various modern refugee crises), The Other Boy by M.G Hennessey (gender transitioning), Shattered by Eric Walters (homelessness, PTSD, and the plight of military veterans), Bifocal by Eric Walters (racism) and We All Fall Down by Eric Walters (the 9/11 attacks).

Taken on their own, every single one of these titles is a perfectly legitimate, even laudable, choice for young students. And most parents would be proud to have a Grade 6 child capable of reading and appreciating such fairly advanced fare. The inclusion of a book about military veterans, moreover, will help assuage concerns that this is a component of a campaign of left-wing indoctrination. But the function of a reading list shouldn’t just be to educate students about current concerns. It should also be to awaken them to the great works of yore, on whose cultural foundation the modern literary firmament was built.

On a purely practical level, one of the functions of older books is that they introduce young readers to words, phrases and cultural references that, though now out of fashion, often will show up on standardized tests and in college coursework. Shakespeare alone created 1,700 English words, which took birth in fits of creation that still manage to take away a reader’s breath. This would include a word I used above, “fashionable,” which first stirred itself in Troilus and Cressida: “For time is like a fashionable host / That slightly shakes his parting guest by the hand / And with his arms outstretch’d, as he would fly / Grasps in the comer: welcome ever smiles / And farewell goes out sighing.” By what definition of “equity” would we deny exposure to such cultural treasures to students—especially public-school students whose parents might understandably wish them to be armed with the cultural tools stereotypically associated with the offspring of elites?

The pattern now is to denude language, not enrich it. In a recent article, children’s author and two-time Carnegie Medal winner Geraldine McCaughrean, put it this way: “While vocabulary used to be ‘free range,’ now it feels policed against political correctness and difficult language.” Words such as “mellifluous,” she said, had been rejected from manuscripts for teenagers because they were seen as too obscure. A “fellow author was saying that ‘superb’ had to be changed because no child will understand it. But they never will understand it if they don’t read it.”

One of the reasons I’ve chosen not to continue my work as a schoolteacher is that I have seen children and young adults gauzed up in the cotton wool of equity mandarins whose mandate is to reduce education to a process of indoctrination. And if a book is seen as interfering in any way with today’s fashionable dogmas, then it is the book that “farewell goes out sighing.”

* * *

This is personal for me. I am writing not just as an educator, but a book lover. When I was an asthmatic child growing up in New Zealand with a sway back, eczema and a raspy cough, I fell in love with a number of novels, none more so than Ballet Shoes, a dazzling 1936 tale of dance and adventure by Noel Streatfeild. My hometown of Christchurch was a parochial, garden city perched on the foothills of the Canterbury Plains—a place where residents were decidedly more interested in sheep than the Bolshoi. The height of sophistication was donning a Guernsey jersey to swan about Merivale Mall. Ballet Shoes took me to another world.

Like all great children’s books, the book provided a connective tissue between my own pedestrian daily life and the possibilities that awaited in the wider world. In my mind, the Fossil sisters—Pauline, Petrova and Posy—had a fourth companion named Carla. I adored my pet lamb Alice and chicken Peck. But, what I really longed for was a “smart motorcar,” a monkey, an ermine-trimmed coat and a long-lost uncle to regale me with stories of “the Continent”— whatever that was. Pink shoulder shrugs, pointy toe shoes and resin romanced my tender soul. True diversity, any good book shows, is about the person, not their race. Streatfeild’s characters brimmed with curiosity, ingenuity and resilience. It never would have occurred to me that these qualities would take any different form if they’d be personified by characters with different skin colors or pronouns.

Reading is a gateway to empathy and understanding. It is also a heady cocktail of language, characters and themes whose lingering memory shape our thinking for a lifetime. A curriculum shaped by equity officers—as opposed by true lovers of literature—will always ill-serve students, because it inevitably will focus on the limits of human experience, not its possibilities. Like so many other school boards, Peel Region has committed itself to teaching students that the defining features of their experience and consciousness is their status as racialized, disabled, transgender, cisgender, refugee, Indigenous, “settler,” black, white—grievances to be catalogued and parsed.

As a teacher, I have had the privilege of teaching unusually smart children. One of my best experiences in this regard came when I taught a class of 18 girls at a private Toronto school, almost all of them true bibliophiles. One of our read-aloud books that year was The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle by the prolific Edward Irving Wortis (who writes under the pen name Avi). The rich language reflects the novel’s 19th-century setting. And the ritual of reading it out in class was a social act that brought us all closer together intellectually. A meeting of minds doesn’t require a sharing of hash tags.

If I did return to the classroom, this is a book I would teach. I would also teach the aforementioned Ballet Shoes, which contains any number of strong female leaders—including the headstrong Sylvia (or Garnie as she’s known), and her sidekick Nana as the unimaginative but necessary voice of reason. Certain boarders at their home can easily stand in as LGBTQ representation. Mr. and Mrs. Simpson, who own an auto-repair garage, represent the cause of the working class and the aspirations toward upward mobility. (They are a refuge for Petrova, the young Russian adoptee who prefers tune-ups to tutus.) Then there’s Madame Fidolia, the former Russian prima ballerina who fuelled my ballet fantasies all those years ago. She turns the young adoptees into professional working children of the stage, teaching them independence, humility and resilience.

Ballet Shoes showed me the many worlds that collided between the two world wars, complete with a magnificent London backdrop, in which nannies took their small charges to the Victoria and Albert Museum on rainy days. This portrayal of a bygone world deserves its place on modern reading lists not because it reflects the world we see around us, but precisely because it does not.