Art and Culture

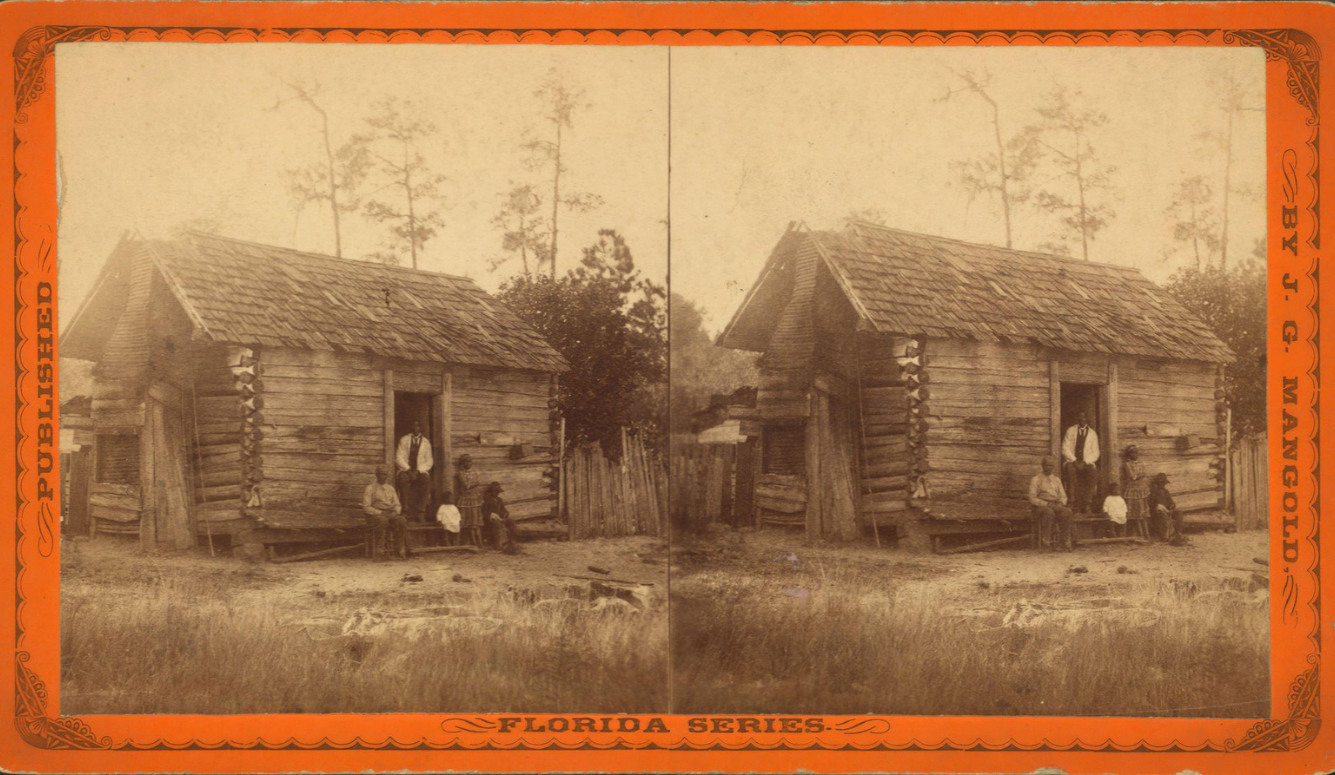

Huck Finn or Uncle Tom?

These great books should be read together, for each illuminates a different part of the American character.

· 8 min read

Keep reading

A New Middle East?

Brian Stewart

· 6 min read

Greta Thunberg’s Fifteen Minutes

Allan Stratton

· 10 min read

Gentrifying the Intifada

John Aziz

· 8 min read

Creative Writing in the Age of Trump

Daphne Merkin

· 7 min read

Podcast #291: Science vs Māori Knowledge

Quillette, Kendall Clements

· 47 min read

In Defence of Jiang Yurong

Aaron Sarin

· 9 min read