Culture Wars

"Dear Millennial...."

Dear Millennial,

I am a 60-year-old white male without a college education. Make of that information what you will. I can lay no claim to be the least racist, sexist, homophobic, or transphobic person you’ve ever met, but I do try to treat people—regardless of their creed, color, gender, orientation, etc.—the way I’d like to be treated. And, to be honest, I probably deserve some of the scorn I often see heaped onto working-class white male Boomers without a college degree. I haven’t been smart with my money. I work in a low-paying service-sector job. I’ve eaten more red meat and rich desserts than is good for anyone, and I like things that every enlightened individual knows are awful: the Eagles, pork chops with mint jelly, the paintings of Bob Ross, Jerry Lewis movies, Billy Joel, cargo shorts, TV shows like Blue Bloods and Castle and Two and a Half Men.

Nevertheless, I am writing to ask you to go easy on me and on my formative cultural influences. The reason for this letter is, of late, I’ve noticed that whenever I speak up in defense of some icon or other, fondly remembered from my youth but since disgraced, I can sense the quiet judgment and consternation of you and other Millennials. Of course, I would like to be more woke—I truly would—but it’s impossible for me to separate myself from the era in which I grew up.

Let us begin, dear Millennial, with Bill Cosby. Bill Cosby has committed terrible crimes. Let us agree that he is a monster and that he deserves to be locked away, probably forever. But, like a lot of monstrous-and-talented people, Cosby isn’t only a monster, and his talent brought my friends and me a great deal of joy as teenagers. Back in the 1970s, we would gather in somebody’s bedroom or basement and we would listen to comedy albums on old-fashioned turntables for hours. These records were like a drug, and once you got hooked, you’d find yourself listening to stuff by George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Lenny Bruce, The Firesign Theatre, and so on. But the gateway drug was always Bill Cosby. His albums were clean enough that no parent could object to them, but funny enough that listening to them seemed somehow indecent. What’s more, Cosby’s specialty was childhood. He talked about frightening fathers, the absurdities of unorganized street football games (“Cosby, you go down to Third Street, catch the J Street bus, and have them open the doors at 19th Street. I’ll fake it to you.”), the terrors of middle school, and the rough-and-tumble of sibling rivalry.

As a Millennial, you’ve grown up in a cultural landscape peopled by all manner of African-American personalities. But in the kind of white-bread Catholic household of my youth, just about the only African-American artists a person could reliably find shelved in the hi-fi cabinet were Nat King Cole and Bill Cosby. It’s difficult to overstate how prominent Cosby was in that virtually all-white suburban world. I spent eight years matriculating at All Saints Elementary School in Portland, Oregon, and never once encountered a black classmate. But, like many of my school friends, I could do a mean impersonation of Fat Albert and many other Cosby characters besides. That might strike you as grotesque minstrelsy or some other appalling species of appropriation, but we weren’t laughing at Cosby’s characters because they were black. We laughed because they were funny.

To this day I keep a tape of Cosby’s album When I Was a Kid in my car (yes, I still have a cassette player in my car). And I still play it, not to celebrate the work of a serial rapist, but to relive an important element of my formative years. Alas, this is not something I can play when you ride in my car, dear Millennial. On such occasions, I toss it onto the backseat along with anything else that may strike you as offensive. That includes comedy albums by George Carlin, who occasionally assumed what is now disparaged as a ‘blaccent’ during his act, and who frequently commented on race relations in politically incorrect routines such as “White Harlem” and “Black Consciousness.” I will also hide my copy of Mac Davis’s Greatest Hits, because it contains the song “Baby, Don’t Get Hooked On Me,” occasionally cited by progressives as one of the most sexist songs of the 1970s (along with Paul Anka’s “(You’re) Having My Baby,” for some reason).

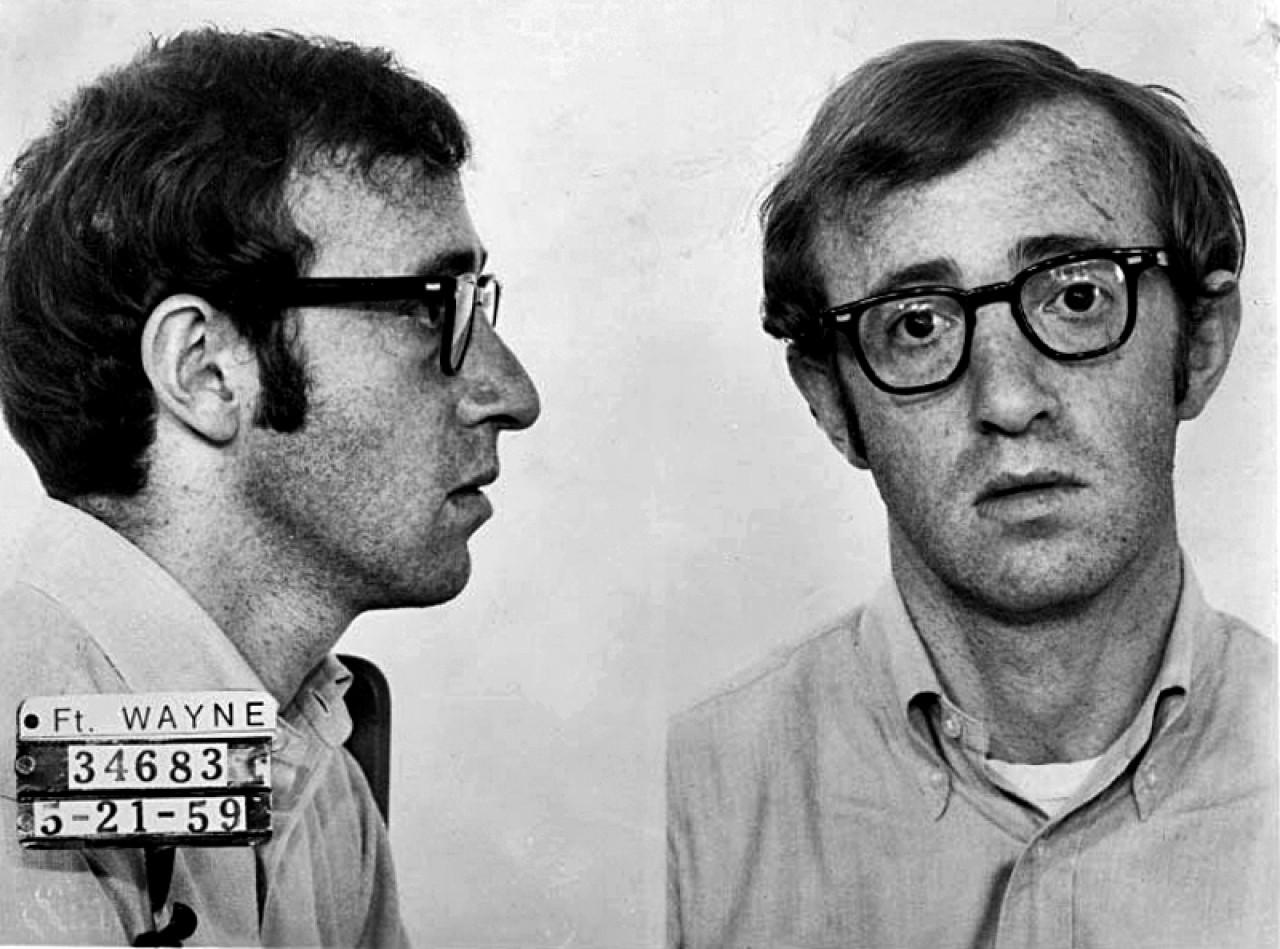

It is almost impossible to discuss the popular culture of the 1970s without mentioning the work of Woody Allen, dear Millennial. His stuff seemed to be everywhere back then. His movies were commercially successful and critically revered, he wrote wonderful comic pieces for the New Yorker, he appeared on the Dick Cavett Show, and my friends and I were belatedly discovering the comedy albums he recorded and released during the 1960s. I have had bits and pieces of Woody Allen’s work floating around inside my head for nearly half a century. (“Don’t knock masturbation; it’s sex with someone I love.” “To you I’m an atheist. To God I’m the loyal opposition.”) To purge our culture of Allen’s incalculable influence, my entire generation and many since would need to undergo some sort of massive deprogramming operation.

While I can understand your generation’s antipathy towards Cosby, I find the hostility towards Woody Allen difficult to fathom. Allen is an 82-year-old man and one highly dubious charge of child molestation is, to my knowledge, the only act of criminality of which he’s ever been accused. This single tawdry accusation was made by his then-partner more than a quarter century ago in the middle of a profoundly ugly breakup. It was thoroughly investigated by the competent authorities, pored over in pornographic detail by a prurient media and public, and more-or-less everyone besides Mia Farrow concluded that there was no case to answer.

And so Allen’s productive career continued until it was engulfed by the #MeToo movement. His latest film, we now learn, may never see the light of day. Despite his advancing years, his prodigious productivity suggests he might have another ten films in him if he is permitted to continue working. And yet the boycotts and social-media shaming campaigns, uninterested in the details of careful inquiries dimly remembered and powered by the righteous zealotry of Millennials like you, my friend, threaten to destroy the twilight career of this singular talent. Even Allen’s lesser works reliably include a few dazzling scenes, or performances, or jokes that make them worthwhile. If his persecutors succeed, then you and I, dear Millennial, will both lose far more than we gain.

If my favorite records and films contain much to offend your generation, you might well recoil from my personal library. I enjoy movies, music, and comedy a great deal but none of those has ever elicited the same passion within me as books. I’m a 60-year-old man who works as a clerk in a bookstore because it’s about the only thing I’m really qualified to do. I’ve been in love with American pop fiction since I first discovered my grandfather’s collection of Travis McGee mysteries back in the late 1960s or early ‘70s. McGee (the fictional creation of John D. MacDonald) was an incorrigible womanizer. If he had had a theme song, it would no doubt be “Baby, Don’t Get Hooked On Me.” He would not have been embraced by the #MeToo generation.

Furthermore, I am a huge fan of the traditional Western novel, a genre that I haven’t noticed much fondness for among the Millennials of my acquaintance. One of my favorite books from the 1970s is The Education of Little Tree, written by Forrest Carter, a pseudonym for the now-notorious racist and Ku Klux Klan member Asa Earl Carter. I read the book and fell in love with it long before the author’s white supremacist past became common knowledge. Nothing I’ve learned about Forrest Carter since has changed my affection for his story. I’ve always believed that each individual contains multitudes, and that the capacity for great evil and great beauty can co-exist inside the same person. Are you too able to appreciate this kind of nuance, dear Millennial?

In 1983, Danny Santiago’s Famous All Over Town was published and immediately heralded as a masterful evocation of life in an East Los Angeles barrio circa 1970. Just about every significant character in the book, including its narrator, is a Mexican or a Mexican-American. Having won early praise, Santiago’s novel seemed to be destined for a Pulitzer nomination when it was revealed that Danny Santiago was the pseudonym of Daniel Lewis James, a wealthy, Yale-educated white male. At which point, charges of cultural appropriation were raised against him. Scholar Arnd Bohm, writing in The International Fiction Review, summed up the response like this:

The reception turned negative and indeed hostile when John Gregory Dunne revealed “The Secret of Danny Santiago” in the New York Review of Books … The reaction ranged from consternation to anger. How could James have managed to dupe the publishers and the critics? How did an elderly affluent white author dare to appropriate the voice as well as the topics of minority writing? The Before Columbus Foundation sponsored a symposium at the Modern Times Bookstore in San Francisco on the question “Danny Santiago: Art or Fraud,” with the consensus opinion of those who participated leaning toward the accusation of fraud.

Needless to say, the book’s reputation never recovered. It ought to be ranked among the best Young Adult novels ever written. Instead, it languishes in undeserved obscurity.

Yes, I realize that cultural appropriation offends you, dear Millennial, but to me it is a vital element of all fictional creation. My personal library contains works in which men wrote from a female perspective (Ernest Gaines’s The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman) and vice versa (Frankenstein, Ethan Frome, etc), whites wrote from the perspective of minorities (William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner) and vice versa (Zora Neale Hurston’s Seraph on the Suwanee), the young wrote from the perspective of the elderly (Little Big Man, a novel narrated by a 121-year old man and written when the author, Thomas Berger, was in his thirties) and vice versa (the aforementioned Famous All Over Town, John Updike’s Terrorist), Jews wrote from the perspective of Christians (Love Story, The Caine Mutiny) and vice versa (Updike’s Bech: A Book).

What seems to have been lost is an appreciation that this kind of cultural cross-pollination is good for literature. Outsiders to a group are often able to see the group in new and surprising ways. Two of my favorite American Westerns—The Heart of the Country and Power In The Blood—were written by an Australian named Greg Matthews, who also had the audacity to pen a sequel to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the quintessential American novel. Cultural appropriation, which you now demand we condemn and shun, dear Millennial, was the force that gave us The Beatles, Panda Express, The Magnificent Seven, and chess. I embrace it, and so should you.

The recent death of Burt Reynolds has caused me to reflect on the 1970s, because Reynolds was the decade’s signature movie star. Although plenty of other ‘70s icons are still breathing, political correctness has consigned many of them to a cultural twilight zone. Al Franken first came to prominence in the 1970s as a writer for and occasional performer on Saturday Night Live. He subsequently rose all the way to the U.S. Senate before being forced to resign as the result of some minor indiscretions and the political calculations of his party colleagues. He might have made an excellent presidential candidate in 2020. Now it’s unlikely that Millennial voters would support him in a run for local dogcatcher. Zero tolerance may someday leave you with a dearth of political, as well as cultural, heavyweights.

The ‘70s also saw the birth of Garrison Keillor’s much-loved radio program, A Prairie Home Companion. But I hesitate to recall my fondness for Keillor and his works now because accusations (which Keillor denies) of inappropriate sexual conduct have left him too as persona non grata with the #MeToo generation. Michael Landon’s TV version of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie books was an iconic artifact of the 1970s but, today, Wilder too has become an embarrassment. Her name was recently removed from a literary award because she wrote like a woman of her own time and failed to anticipate the political correctness of ours. The 1970s was the decade in which I discovered the writings of Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, and H.P. Lovecraft, all of whom, like Wilder, failed to foresee the mores of our era. And so, they too have fallen out of favor with people like you, dear Millennial, who know only of their sins and care nothing for their saving graces. Lovecraft, like Wilder, recently had his connection with a prestigious annual literary award terminated on account of his racism—a racism only evident in a tiny fraction of his works, mostly minor ones.

As a child I devoured not only the pop fictions of my own era (Jaws, The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby) but also that of my parents’ and grandparents’ eras (Gone With The Wind, Rebecca, Peyton Place, From Here To Eternity). Those earlier eras produced plenty of pop culture that, even by the comparatively lax standards of the 1970s, was considered problematic: Charlie Chan movies, Amos ‘n’ Andy…even Gone With the Wind was beginning to furrow brows by then. But I didn’t think any less of my parents or grandparents just because society’s brave new cultural arbiters had now deemed a few artifacts of their youth ‘problematic’ and ‘inappropriate.’

Every generation produces its fair share of embarrassments, but I don’t see any reason to scrub them from the historical record. It’s kind of a shame that the Amos ‘n’ Andy show is considered too politically incorrect to be broadcast on NetFlix the way other old shows like The Andy Griffith Show and The Twilight Zone are. For all its casual racism, the series was a showcase for the amazing comic talents of its African-American cast, particularly Alvin Childress, Spencer Williams, Tim Moore, Ernestine Wade, and Amanda Randolph (the first African-American ever to star in a regularly scheduled network TV show, according to Wikipedia). Those actors were every bit as talented as the cast of I Love Lucy but they are largely forgotten while I Love Lucy plays on despite its equally casual misogyny.

Last Christmas, I took a temporary job at a local Amazon warehouse in order to make some extra money. The assaultive hip-hop music that played incessantly over the loudspeaker there, with its frequent references to ‘niggas’ and ‘bitches,’ struck me as far more racist and misogynistic than anything I had ever encountered in an episode of either Amos ‘n’ Andy or I Love Lucy. But I never complained or asked for it to be changed. I’m tolerant of the political incorrectness of your generation. All I ask, dear Millennial, is that you reciprocate. I cannot rid my conversation or cultural heritage of any and all positive allusions to Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, The Dukes of Hazard, Chico and the Man (in which Freddie Prinze, a man of German and Puerto Rican ancestry played a Chicano stereotype that some people found offensive), Garrison Keillor, Al Franken, Mac Davis, or any other icon of my youth, and nor do I want to.

As a result, I am likely to say things from time to time that strike you as wildly inappropriate. I get that but I don’t feel that I should be expected to apologize for it. What you need to understand it that Bill Cosby helped us to laugh during an era when there wasn’t much to laugh about—in which the news and much of the cultural conversation were dominated by the war in Vietnam, campus unrest, street violence, and political assassinations. Chico and the Man debuted one month after Richard Nixon’s resignation. Yeah, it was a stupid caricature of Chicano culture in East L.A. but, after enduring the slow-motion train wreck of Watergate for two years, man, did it feel good to laugh again.

You have already begun sending some of your own pop icons into cultural purgatory for relatively minor sins. I suggest that you reconsider this puritanical policy, dear Millennial. Creative artists, like the rest of us, are granted only a finite time on earth. It would be a shame to reduce the number of good jokes, entertaining TV shows, moving novels, and enjoyable movies in the world out of a misguided effort to purify the culture of every last flawed creative mind. Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor and Forrest Carter each produced some of the most memorable cultural artifacts of their eras. Let the justice system decide whether the many and various #MeToo casualties belong in jail or not. As long as they are free to produce their creative work, we ought to let them do so. Boycott it if you must, but don’t block or embargo it. Some day, when the controversies surrounding their recent indiscretions has died down, you may wish you had a few more James Gunn movies to watch, and a few more Louis C.K. comedy routines to laugh at.

And if you insist on purging your brain of some of the more problematic voices of your generation’s culture, so be it. But please don’t ask me to purge my brain of the more problematic voices of my generation. Those voices have been in there for a long time. And sometimes they are the only ones that truly speak to me.