Fiction

Read Houellebecq To Free Your Mind

Houellebecq has grave doubts about the net effect of the sexual revolution on human well-being.

Let’s say that you, like many Quillette readers, are part of the broad coalition that aims to promote greater engagement with dangerous ideas and fight political correctness – call it cultural libertarianism if you wish, but in reality the coalition includes many social conservatives and others who don’t really fit that label. What should you read? Who should your intellectual heroes be? An obvious answer is John Stuart Mill; approving references to Mill’s wonderful On Liberty have become something of a ritual for those of us with such concerns. But there’s room for more heroes besides Mill, and room for disagreement and debate about who those figures should be. In this essay, I’d like to suggest that the contemporary French novelist Michel Houellebecq may be such a figure. Though Houellebecq has a large international audience and many Quillette readers are surely familiar with his work, I find that his name isn’t invoked that often in the discussions of cultural issues with which we are concerned. But it should be. Houellebecq has something to offer to those who genuinely yearn for free discussion of dangerous ideas, and in particular free discussion of the underlying principles on which post-60s sexual culture is based.

A brief overview of Houellebecq’s career arc lends clues as to where the attraction lies. After writing poetry and an essay about Lovecraft, Houellebecq, already in his mid-thirties, published Whatever, a novel largely about two lonely professional men on a business trip, to critical acclaim in France in 1994. The 1998 follow-up, The Elementary Particles (published in the UK under the title Atomised), about Michel and Bruno, two sexually-dysfunctional half-brothers navigating midlife crises, reached an international audience and may be his most enduring work, despite gravely offending Michiko Kakutani. More novels followed; notably, on the book tour for 2002’s Platform, Houellebecq got into some trouble for calling Islam “the stupidest religion,” which led to racial incitement charges. His most recent novel, 2015’s Submission, depicts a future France under the leadership of a moderate version of the Muslim Brotherhood, and was released the same day as the Charlie Hebdo massacre; Houellebecq was on the magazine’s cover the week of the attack. Needless to say, when the novel’s English translation was released later that year, Michiko Kakutani got offended all over again. Some things never change.

Michiko Kakutani says Houellebecq's "ugly" novel about France as Muslim state is "done with an extremely heavy hand" https://t.co/zgvn2vRj0M

— New York Times Books (@nytimesbooks) November 4, 2015

Already, it’s plain what might make Houellebecq appealing to someone with heterodox tastes: he is a high-profile figure who has several times faced prototypical versions of what we might today call outrage culture, and not only survived the experience but managed to grow his fame in the process. It’s not that he’s immune to the pain that being on the receiving-end of hostility can bring: in Public Enemies, a collection of correspondence with the French public intellectual Bernard Henri-Levy, he discusses in some detail the discomfort of being on the receiving end of such salvoes. But he manages to absorb the pain and keep writing. That, in and of itself, is admirable, but hardly unique; there are, happily, other public figures who face the outrage machine without blinking. What distinguishes Houellebecq is the same thing that brought him to the public eye in the first place: the ideas present in his novels. And, though there are other themes that are inarguably important in his work – religion and technology are obvious ones – it’s his treatment of sexuality that, I think, is foundational to his cultural perspective.

To wit, Houellebecq has grave doubts about the net effect of the sexual revolution on human well-being. One recurring consideration in his novels is the winners and losers of the sexual revolution; perhaps the disentanglement of sex and marriage has left some people better off, but not everyone, and to turn an eye towards those who suffer is part of his work. “I show the disasters produced by the liberalization of values,” he has said. These “disasters” take several forms; one of the most prominent is the fate of the ageing. What happens to people – women in particular – who are no longer considered attractive? (Men face the same challenges, too, in Houellebecq’s universe, but not with the same urgency, for various reasons; in any case, as will be discussed below, men have more immediate challenges of their own to deal with in the post-sexual-liberation world.) Passages like the following, from The Elementary Particles, provide Houellebecq’s answer:

Women who turned 20 in the late Sixties found themselves in a difficult position when they hit 40. Most of them were divorced and could no longer count on the conjugal bond – whether warm or abject – whose decline they had served to hasten. As members of a generation who – more than any before – had endorsed a cult of youth over age, they could hardly claim to be surprised when they, too, were dismissed in turn by succeeding generations. As their flesh began to age, the cult of the body, which they had done so much to promote, simply filled them with disgust for their own bodies – a disgust they could see mirrored in the gaze of others.

Brutal stuff – but maybe you know people in that position; I certainly do. With the disentanglement of sex from its place within relationships of lifelong commitment, being attractive when one is young is no longer any sort of insurance against loneliness and despair when one is old. It’s quite possible to reach age 40, get a divorce, and suddenly realize one’s looks, and with them much of one’s cultural capital, have eroded.

Thus, The Elementary Particles is populated with graphic descriptions of the effects of age on one’s attractiveness. Bruno’s mother is sketched as follows: “she was 45 years old now and her vulva was scrawny and sagged slightly, but she was still a very beautiful woman.” Christiane, a biology professor, who “had probably been quite pretty once,” declares that her vulva “already looks a bit like an old woman’s cunt,” and attributes this change to “the breakdown of elastin during mitosis.” In another passage, Bruno describes his ex-wife wearing lingerie he had purchased for her as an anniversary present: “her sagging arse was squeezed into the suspenders and her tits had never really recovered from breastfeeding.” And again, all of this description of ageing is relevant because of its relationship with despair. Christiane suggests that women who grow old alone suffer more than men do: “they try to trade on their looks, even when they know their bodies are sad and ugly. They get hurt, but they do it anyway, because they can’t give up the need to be loved.” In a society that treated marriage as a permanent bond and extramarital sex as immoral, these women might have better outcomes; in this society – at least as Houellebecq sees it – their lot is sadness and loneliness until death.

As for men, how do they make out in a post-sexual-revolution society? One of the other issues with which Houellebecq is concerned is extreme inequality among men in sexual outcomes. A central passage of Whatever lays out a thesis:

Just like unrestrained economic liberalism, and for similar reasons, sexual liberalism produces phenomena of absolute pauperization. Some men make love every day; others five or six times in their life, or never. It’s what’s known as the ‘law of the market.’ In an economic system where unfair dismissal is prohibited, every person more or less manages to find their place. In a sexual system where adultery is prohibited, every person more or less manages to find their bed mate. In a totally liberal economic system certain people accumulate considerable fortunes; others stagnate in unemployment. In a totally liberal sexual system certain people have a varied and exciting erotic life; others are reduced to masturbation and solitude.

Whatever embodies the latter scenario in the character of Tisserand, a feckless, desperate, thirty-something would-be ladies man. (Bruno, in The Elementary Particles, is a more nuanced version of this same character type.) Though Tisserand is financially successful and good at his job, he is “so ugly his appearance repels women” and has a face like a “buffalo toad,” and, though the narrator notes that “charm is a quality which can sometimes substitute for physical beauty – at least in men, anyway,” Tisserand doesn’t have any. On the contrary, his repeated sexual failures have left him chronically anxious and openly desperate in the presence of women; his flirtatious gestures are unsubtle and cringeworthy. Late in the book, after one particularly disturbing such episode, the narrator tells Tisserand that he will likely never sleep with another woman, that he has missed out on the possibility of any sort of sexual happiness, and that “an atrocious, unremitting bitterness will end up gripping your heart. For you there will be neither redemption nor deliverance. That’s how it is.” The character of Tisserand, then, represents the dark side of a laissez-faire policy of sexual relations: in such a framework, inequality will develop, and people like him will likely never find mates.

These two major downsides that Houellebecq sees in the sexual revolution – the fate of the aging and extreme inequality in sexual pleasure among men – are, to be sure, buttressed by other insights on the subject; both Whatever and The Elementary Particles discuss the erosion of the possibility of love in contemporary culture, for instance. But almost as interesting as the contours of the sexual dystopia Houellebecq perceives us to be in is the question of what to do about it. If we begin to suspect that sexual relations ought to be done differently, the question of how they should be done and how to get there becomes relevant. It’s in this light – with the background of Houellebecq’s earlier portrayals of sexual misery firmly in mind – that I think Submission, and its depiction of a future Islamist France, can be read most provocatively and interestingly: not as a cautionary tale or as a fearful screed, but as a straightforward presentation of what its author takes to be a somewhat desirable possibility for the future.

In short, in the Islamic state Houellebecq envisions, the “disasters produced by the liberalization of values” are neutralized. Intimacy and matrimony are connected, and each is a life-commitment, meaning that those who do get married need not worry about ageing alone in most circumstances. At Submission’s outset, its narrator, François, is a classically Houellebecquian character: while he, a famous professor, attracts and sleeps with attractive women (mostly his students), it’s always pretty clear to François that his current partner won’t stick around, and he is concerned with his own ageing and aloneness, both physically and intellectually; a nihilism pervades his relationships. By the novel’s end, buoyed by the reinstitution of patriarchy and the knowledge that he’ll have a satisfying family situation, these anxieties no longer preoccupy François: “I started to realize – and this was a real novelty – that life might actually have more to offer.” And while we are never given much direct insight into what women in the novel think of the new sociopolitical regime, the problem of their ageing alone is sidestepped as well. We are given a glimpse, for instance, of Malika, who is the first wife of Rediger, the president of what is now Islamic University of Paris – Sorbonne. In another Houellebecq novel, a woman like Malika – married to a powerful man, beginning to age – might have ended up sad and desperate at a New Age orgy weekend. Here, she is an extremely important part of a high-powered household.

As to Houellebecq’s other big concern with modern sexual politics, inequality in men’s sexual outcomes persists in Submission’s universe – it is a polygamous society, after all, and Rediger defends this polygamy on Darwinian and utilitarian grounds – but what’s different is that sexual outcomes for men are now dependent, at least partially, on virtue. An effort is made to make sure that what the Islamists perceive to be the right men wind up getting laid, supplanting the purely laissez-faire, anarchic sexual marketplace. This can be seen most clearly in the hints Rediger gives of a concerted state effort to make raise the social status of professional intellectuals (exclusively male by now), thereby making them more attractive to women. “With the right education, [women] can be convinced that looks aren’t what matters … to a certain degree, women can even learn to find a high erotic value in academics,” Rediger says. “On the other hand, we can always just pay teachers more, which simplifies things.” In some cases, even more direct intervention by the Islamists is called for: François is shocked to find that Loiseleur, a brilliant but socially-awkward colleague who François has always thought would never get married, now has a wife, thanks to his bosses. (“Yes, yes, a woman – they found me one,” he says.) The changing fortunes of intellectuals are relevant to Houellebecq’s longstanding sexual concerns: in a memorable passage from The Elementary Particles, Bruno wonders, while watching attractive female students flirt with their less-intellectual classmates, what the future of the life of the mind would be if women no longer prized learnedness in sexual partners. The Muslim Brotherhood of Submission, by consciously building a society in which intellectuals have good sexual outcomes, works to address these concerns, even as they leave some measure of sexual inequality in place.

Though others have noted Houellebecq’s favorable portrayal of Islamic France, this reading of Submission may still be somewhat shocking; the novel, seen in this way, is likely much more transgressive than it would be if Houellebecq had just written the Islamophobic screed that his critics reflexively assumed he had written. But I do think the interpretation is justified: the sexual concerns with which his early novels were preoccupied are successfully addressed by the new regime. To be sure, there are other concerns in their place; young women under the rule of the Islamists, now deprived of career opportunities, often seem destined to a state of perpetual adolescence. (When an interviewer objected to Houellebecq’s claim that in Submission “things don’t go all that badly, really,” by bringing up the much-diminished role of women, Houellebecq responded “yes, that’s a whole other problem.”) But, crucially, the sadness that might otherwise befall a Christiane or a Tisserand is avoided. Houellebecq has said that he avoids trying to change society: “That’s the difference between me and a reactionary. I don’t have any interest in turning back the clock because I don’t believe it can be done. You can only observe and describe.” But whether by accident or design, the universe described in Submission is a place where many of the hardships its creator has spent much of his career documenting get eradicated, almost literally overnight. Adam Gopnik, in an indispensable essay, has argued that Houellebecq longs for the Gaullist gender politics of the France of his youth; Submission outlines one barely-plausible way something similar could come about in the 21st century.

Stepping back from this treatment of Houellebecq’s texts, we return to the issue with which we started. Why does Houellebecq’s handling of sexuality matter in terms of how he’s perceived by those of us who seek to engage with dangerous ideas?

It matters because we’re at a moment in which the post-sixties sexual norms are being increasingly questioned, particularly by those who they marginalize. A chapter in Angela Nagle’s Kill All Normies,“Entering The Manosphere,” chronicles some of the varieties of this rebellion: the pick-up artistry of the Return of Kings crowd and the frank patriarchalism of Gavin McInnes, for instance. There are also certain strains of this intellectual ferment that have a vaguely Houellebecquian ring, such as the ideas of the men’s rights theorist F. Roger Devlin, who argues that “the breakdown of monogamy results in promiscuity for the few, loneliness for the majority.” Nagle agrees, and details some specific examples of the real-world consequences of sexual inequality, pulled from Reddit’s incel forum, followed by a brief discussion of the mass murderer Elliot Rodger, who (unwittingly following a piece of advice Whatever’s narrator gives to Tisserand) went on a shooting rampage targeting the sort of attractive women who had rejected him. To a Houellebecq reader, the whole conversation strikes some uncanny chords.

Houellebecq deserves credit, then, for anticipating and dramatizing an aspect of contemporary sexual culture that is often ignored in the popular press. In his novels, we see not only the sadness of what we’d today call an incel (for instance) but also the line of traumas, choices, and accidents of genetics that lead someone down that path; people who in the course of our lives we might find it easier to dehumanize, or to not contemplate at all, are given a fuller treatment. This is immensely valuable if our goal is to better understand the cultural moment in its complexity.

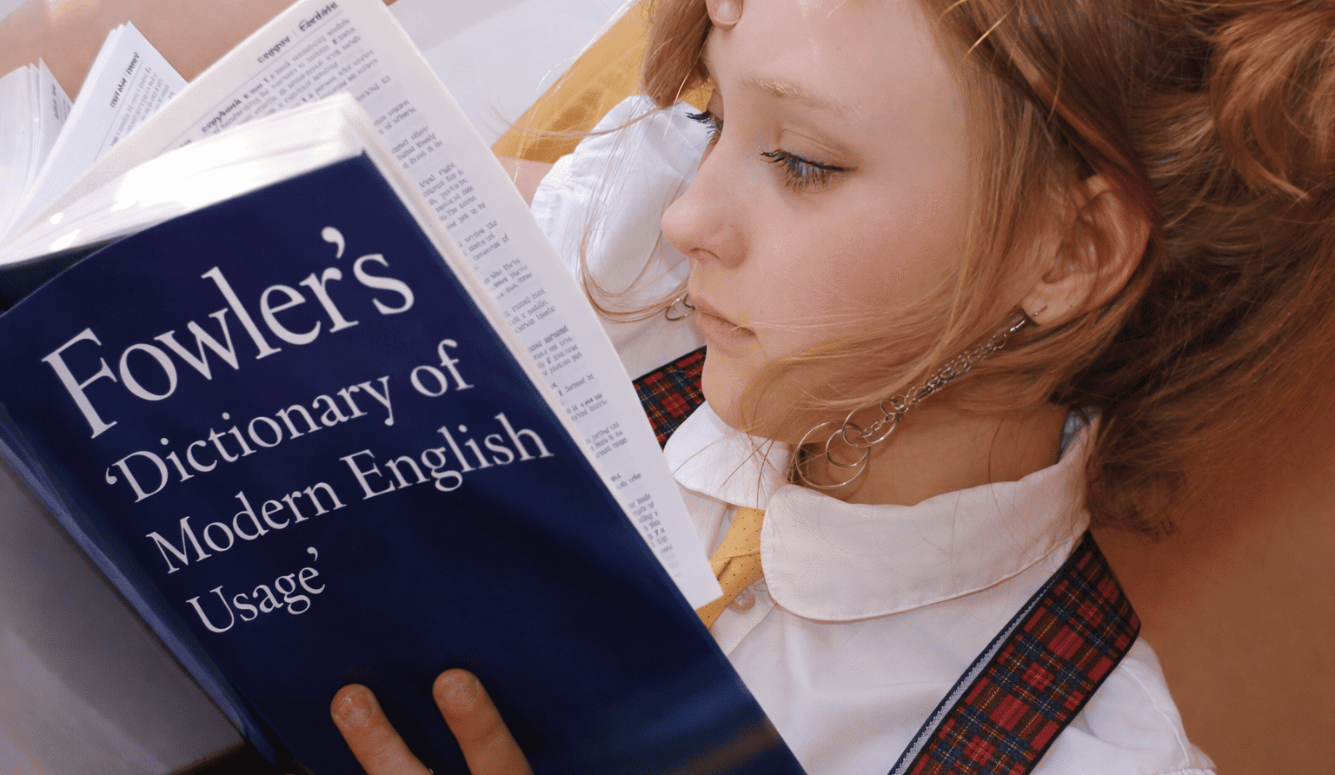

But his use to us goes further. For not only are people like Devlin invested in highlighting the flaws in contemporary sexual practices, they are often invested in changing practices, instituting new forms of sexual morality, often on a level of personal ethics, but also on a level of mass politics. And here one is faced with an epistemic impasse: it seems difficult to know what the best set of sexual mores is. Speaking personally, all I’ve ever lived in is this post-sixties sexual playground, a culture that (just as both Neo-Marxists and Neo-Reactionaries would predict) is hell-bent on making its own values seem obvious, unassailable, undebatable; with some work, I can begin to doubt the value of this form of culture, but, not having anything to compare it to, it’s hard to reach the point of confidently asserting any alternatives as better, or confidently agreeing with the assertions other theorists might make. Should we have patriarchy? Sexual anarchy? Polygamy? Should we follow Freddie deBoer and insist that society has no obligation to people who can’t get laid? On a personal level, how should we handle our sex lives? And on the basis of what criteria should we make these judgments?

Questions like these are, in fact, one of the best reasons for reading, and especially reading fiction – as Mark Edmundson might put it, the books you read will be meaningful to you insofar as they touch on your Final Narrative, the story you have cobbled together about where you’re going and what matters to you. In Houellebecq, those of us who wonder about the relative value of our sexual culture find a rare writer who is largely disillusioned with that culture, who is willing to talk through its costs and benefits in a sustained way, and who gives us thought-experiments about how we might survive, both as individuals and as groups. Is joining a swingers subculture, as Bruno and Christiane do in The Elementary Particles, sufficient to keep the loneliness at bay? Is the patriarchal society instituted in Submission a goal worth aiming for? In these books, possibilities are presented, explored, stress-tested; we get to envision what different scenarios may look like, and think through their implications. This improves the epistemic situation; it can help us feel less at sea as we make personal and political decisions. Houellebecq gives us the opportunity to imagine possibilities with him, and that can be fruitful to our understanding of our own path through life.

This all sounds like obvious and even banal work for a writer to do – to examine the mores of the moment critically, and talk through potential alternatives – but in practice, novelists like Houellebecq are in short supply. Maybe this has to do with the values of the publishing industry, in which fiction with a whiff of conservatism to it tends to have a hard time, and which seems to be getting ever more controversy-averse. Houellebecq himself has said that Whatever, the novel that made his name in France, could never be published today: “our societies have come to a terminal stage where they refuse to recognize their malaise, where they demand that fiction be happy-go-lucky, escapist; they simply don’t have the courage to face their own reality.” So it may be that Houellebecq’s career path could never be followed today, and he can be seen as a dinosaur, a relic, someone who slipped past the bouncer and achieved a degree of popular status at a different moment when it was more permissible for dangerous ideas to proliferate.

Maybe we can get there again. In the meantime, reading Houellebecq, and thinking about what he represents, is a good first step. The formal elements of his literary stardom – the way he seems to absorb every controversy while continuing to write, continuing to gain popularity, never wilting under the gaze of the outrage machine – are inspiring, to be sure, providing a target for conservatives and cultural libertarians to aim for. But it’s the content of his books that sets him apart, for by reading those books, we can gain a degree of internal freedom: the means to slip the mind-forged manacles endemic to our time and place and dream of something else. Houellebecq has found a way to look at contemporary sexual practices from the outside, as something to be questioned rather than taken for granted. By learning to question as he does, we, too, can free ourselves from the compulsion to treat the status quo as inevitable.