Israel

From Gaza to the Ivory Tower: The War on Israel

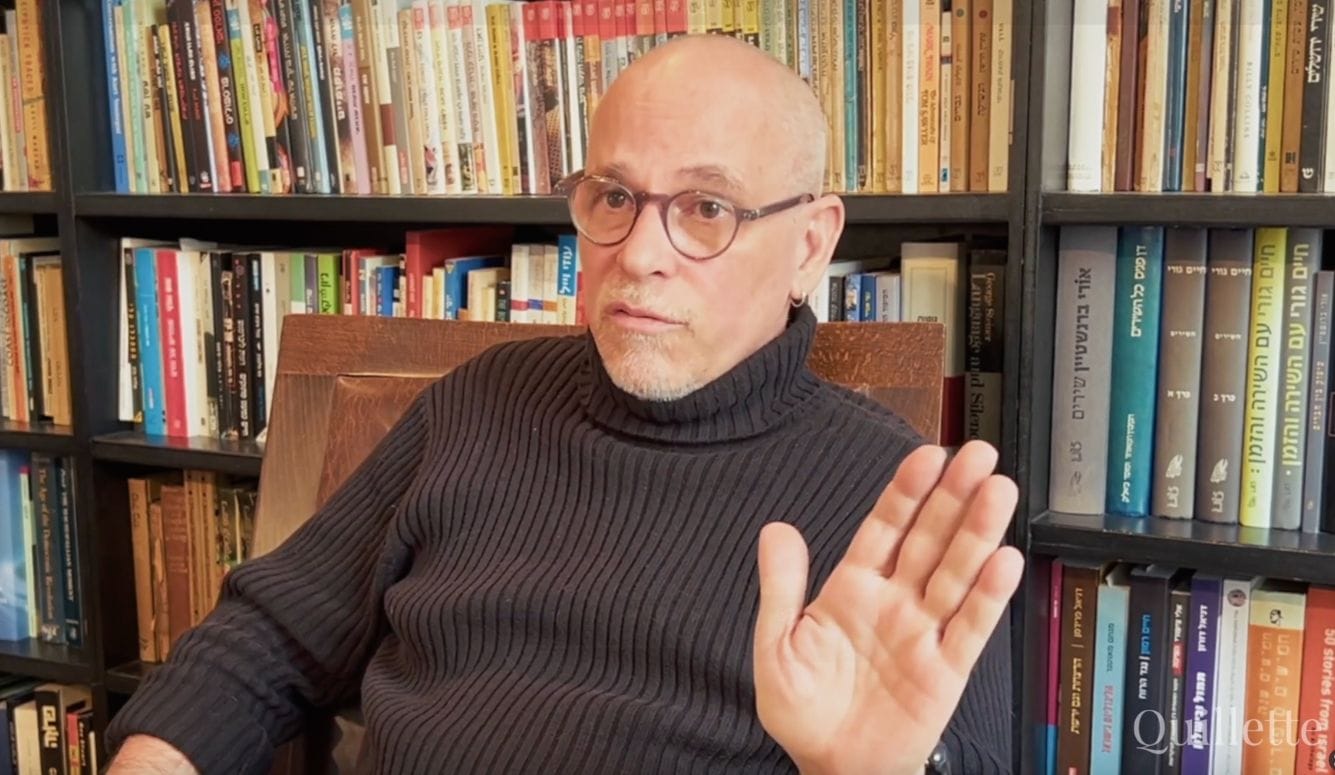

An honest conversation with the hard-hitting Israeli historian Gadi Taub.

On 9 March, Pamela Paresky sat down with Gadi Taub in Tel Aviv to discuss the war in Gaza, the failures of Israel’s security establishment, and the ideological forces—both inside Israel and across the West—that have undermined the country’s ability to defend itself. Their wide-ranging conversation covers everything from 7 October and the erosion of Israeli deterrence to the rise of postcolonial ideology, the crisis of liberalism, and the battle for narrative power in a media-saturated world.

I. Israel’s Security Threats and Western Denial

Gadi Taub:

Our last conversation happened during some of the darkest days—probably the darkest. I felt like our blood was in the water, that we might not recover our deterrence. And in this neighbourhood, as you can now see in Syria, without deterrence—if you’re not strong—sooner or later, you’re dead.

That’s how it felt. We had a hostile American administration, something people are only now beginning to understand. Those of us who follow American politics already knew it was hostile. Biden was hugging Netanyahu over the table while kicking his shins under it. But we didn’t know the full extent. They were stepping on our oxygen supply—cutting off ammunition. It wasn’t just the large bombs. The army was even complaining about D-9 bulldozers—the armoured bulldozers that let you approach buildings without risking soldiers’ lives. If you can’t bomb from the air due to civilian risk, you use D-9s. We had bought 150 of them, but we weren’t allowed to receive them. I heard from people in the army that the lack of those bulldozers was costing us lives—daily.

It was a very dark time. If you remember, I said we were facing a decade of wars to break the noose Iran had been tightening around us—just like the noose Nasser tied around us in the mid-1950s. It took 25 years to break that pan-Arab effort to destroy Israel. Happily, I may have been wrong about the timeline. This war—we don’t really understand it here in Israel, partly because of the poisonous press—but we’ve almost destroyed “the Shi’ite axis of evil,” as the Prime Minister called it. That’s something I thought would take a decade.

I’d predicted the next war would be with Hezbollah, and it would be terrible—more terrible than any war we’ve experienced. We believed it was coming once Gaza was dealt with. There were 150,000 missiles pointed at us, and we knew we couldn’t allow this monster to sit perched on our northern border, driven by a Nazi-inspired ideology. We had to fight, even at the cost of 15,000 civilian casualties, as some papers predicted. No one anticipated the beepers.

I remember sitting in my studio doing the Israel Update podcast with Mike Doran, who called it the “Grim Beeper.” No one imagined we could turn the tide like this. What Netanyahu managed to do—facing a hostile US administration—was unprecedented. No Israeli Prime Minister has managed to continue a war for long under American resistance. Whenever we didn’t finish a war quickly—like the Six-Day War or the destruction of the Syrian army in two days—eventually an American administration would say “enough,” and we had to obey. But this time, we didn’t.

Netanyahu escalated very carefully. He targeted individuals already wanted by the US—people with bounties on their heads and the blood of Marines from Beirut on their hands. The US couldn’t criticise us for those strikes. That allowed Israel to escalate gradually and destroy key Hezbollah capabilities. We toppled the Assad regime through proxies, took out air defences in Iran—and now, the question is: Will we finish the job?

Finishing the job means taking out Iran’s nuclear program. Most people don’t know this, but when Biden was elected, Israel’s existence was in real danger. Back then, Iran had around 500 centrifuges enriching uranium. Now, under Biden, they have over 13,000. That’s just in four years. If Kamala Harris had won this next election, Iran would have had the bomb—unless Israel defied everyone and took action. But doing that without US backing is almost impossible.

We pundits talk about this, but the truth is, we don’t know what Israel’s actual military capabilities are. Taking out Iran’s nuclear program would require a sustained campaign. Without US support, it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible. Still, we are in a better place now. Things are changing daily, and while I don’t know if the next US administration will help, it’s clear they won’t protect Iran’s nuclear program the way this one has.

But Hezbollah is still there, and we haven’t finished the job. I worry we’ll end up with half-measures in Lebanon and a problematic situation in Syria, where Iran has been expelled, but Turkey is now dominant.

Pamela Paresky:

Talk about what’s happening right now in Syria. We’ve seen some disturbing images coming out of there.

GT:

Yes. If you look at the press now, everyone’s talking about this “new” Jolani—he’s showing up in a tie and tuxedo. But these jihadists all share the same murderous ideology. We shouldn’t expect Western values or behaviour from people aligned with Al-Qaeda or ISIS. And we shouldn’t assume the same kinds of incentives and deterrents we use in the West will work.

That was our big mistake with Gaza. All our intelligence said Hamas wouldn’t want to jeopardise their economic progress. But they are religious zealots. They take their religion very seriously—so seriously that it includes a horrifying sadism. Just look at the pictures. This isn’t a conflict you can manage with Western logic.

Yes, we’ve weakened Iran significantly, including kicking them out of Syria. But now Turkey is close to our border. And Turkey is more serious than Iran. It’s a stable state with a real economy and a real army. Iran has missiles, but not much of an army.

We’re now in a totally different situation. We thought we were about to be suffocated by Iran. But the world’s willingness to accommodate Iran has been a sobering reminder of how the West has lost its immune system. It doesn’t recognise threats. It doesn’t recognise the forces that can destroy it. It’s obsessed with its own conscience instead of confronting reality. Saying the right thing has become more important than doing the right thing. Grandstanding now trumps moral action.

I can give you a concrete example. Igal Carmon, head of MEMRI—the Middle East Media Research Institute—collected sermons from imams across North America. He found that about 95 percent of them were wildly antisemitic. Some even incited violence against Jews. He assumed Jewish organisations would raise the alarm. They didn’t.

Many were more concerned about seeming Islamophobic than about protecting their own communities. Carmon said he managed to get a hearing with the Conference of Presidents. But the focus of the meeting wasn’t the content of the sermons—it was how he collected them. Did he eavesdrop? Was it legal? But it was all public content, all online. He just speaks Arabic.

Nobody would touch it—except a few ultra-Orthodox groups and some on the political right. The Centre and Left wouldn’t go near it. And this wasn’t new. Back in 1994, when Yasser Arafat arrived under the Oslo Accords, Carmon was one of the first to sound the alarm. Arafat gave speeches in Arabic calling for jihad against Israel—while telling Western audiences he was committed to peace.

He compared it to the Prophet Muhammad’s treaty with the Jews of Khaybar—an agreement he later broke. Arafat was essentially saying, “Don’t worry, this isn’t real peace—it’s just a phase in the war.” Carmon translated those speeches and took the videotapes to journalists. One of Israel’s top journalists—Nahum Barnea—refused to publish them.

According to Carmon, Barnea told him, “There is no such thing as truth. Every story serves some ideological purpose—and yours serves the enemies of peace.” (Barnea denies saying that. When I republished it, I was threatened with libel—but nothing came of it.)

Back then, the press and political elites believed the public was too hysterical and untrustworthy to hear the truth. They thought they could bridge a temporary period of confusion until everyone came around to peace. So they hid the truth. They thought democracy’s problem was the citizens—that without citizens, everything would work fine. Give them only what the elites think they can digest—a vegan diet of news.

PP:

Is that what happened before October 7?

II. Israel’s Failures on 7 October

GT:

I think the peace mentality had penetrated so deeply that it created a mindset where the overarching assumption was: Everybody ultimately wants peace. One of my friends puts it like this—“In every terrorist, there’s a small inner Jefferson just struggling to get out.” So if we just create the right conditions, if we let them prosper economically, then everyone will come to see that we all share the same goals. That assumption misled our intelligence services into believing that economic betterment would naturally lead to peace. It went so far that on the night between October 6 and 7—when all kinds of warning signs were popping up of an imminent attack—they still didn’t act. One of those signs was the sudden activation of Israeli SIM cards.

PP:

Most people probably aren’t aware of this. Hundreds of Israeli SIM cards were activated in Gaza that night. What would the purpose be? Communication once they crossed into Israel?

GT:

Yes. There are two Palestinian cellphone companies, but reception inside Israel isn’t reliable. So if you’re planning an invasion, you’d need access to the Israeli network. When a large number of Israeli SIM cards were suddenly activated, it was a clear sign of preparation. They had done it before—it could have been a rehearsal—but there were other signs too. For the first time, senior Hamas leaders, including Mohammed Deif, went into the tunnels. The only exception was Yahya Sinwar. Intelligence knew they had gone underground.

Shabak—the Shin Bet, which is responsible for intelligence in Gaza—interpreted this the wrong way. They thought Hamas was preparing for an Israeli invasion, not launching one. And here’s the thing: Shabak had become addicted to technology like the rest of the army. As my colleague Mike Doran puts it, we were thinking in terms of Star Wars, and they beat us with Mad Max—low-tech versus high-tech. We thought we had it figured out, but Sinwar knew us well. He had studied us from inside our prisons. All operational orders were communicated through written notes. He used his phone only to feed us disinformation.

PP:

But even with low-tech methods, how do you hide thousands of people preparing to invade?

GT:

Exactly. You can’t. But Shabak’s obsession with signals intelligence meant they neglected human sources. We had none in Gaza—believe it or not, zero. While the Mossad could track Nasrallah’s every sneeze in Lebanon, Shabak was blind in Gaza. And it wasn’t just the over-reliance on tech—it was also the Western peace-process bias that shaped their interpretation of the data.