Blog

7 October, One Year Later with David Benatar: Quillette Cetera Episode 40

On the anniversary of 7 October, philosopher David Benatar discusses the ethical questions it raises and about his new book, “Very Practical Ethics.”

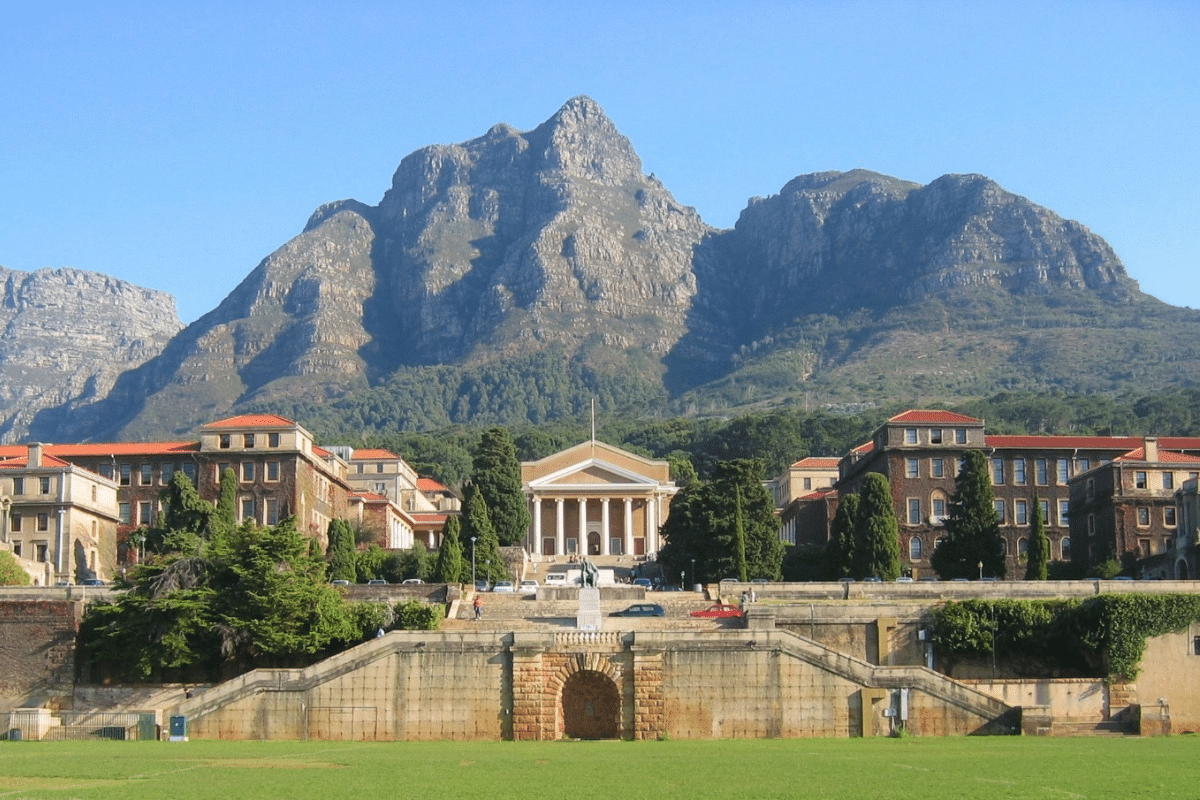

Until recently, David Benatar was a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, where he also directed the university’s Bioethics Centre. He is widely known for his controversial and challenging views on topics like antinatalism—captured in his groundbreaking book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence—which argues that bringing new life into the world inevitably leads to suffering.

In addition to his work on antinatalism, Benatar has written extensively on practical ethics, morality, and human suffering, and his most recent contributions to Quillette have focused on the conflict in Israel and rising antisemitism in the Anglosphere.

In this conversation, we reflect on the anniversary of 7 October and the ethical questions it raises. The conversation concludes with a discussion of his new book, Very Practical Ethics: Engaging Everyday Moral Questions (2024).

ZB: Yesterday was the anniversary of October the 7th. What do you think we’ve learned over the year?

DB: Well, I’m speaking from Toronto, and it’s still October the 7th here. I think we need to clarify your question, because when you ask what we’ve learned, it really depends on who you mean by “we.” Some people haven’t learned anything, while others have learned a lot. For some, October 7th, 2023, didn’t really change their overall understanding of the situation, although it might have been intensified by the events of that day and certainly by the events that followed. So, I think a lot depends on who the “we” is.

ZB: I mean, I’m not Jewish, but I’ve met many Jews over the past few months, and prior to meeting them I didn’t know much about antisemitism or Israel. October 7th was sort of a baptism of fire—excuse the pun, a Jewish baptism of fire.

In the big scheme of things, in the history of the world, does October 7th really matter, or was it just a blip in the timeline?

DB: Well, sadly, it has many historical antecedents. There’s nothing new about what happened then. But every time it happens, people wonder, “How is this happening again? Has nothing been learned from the past?” For many, nothing has been learned. Some have, but it’s hard to know what to do with that knowledge. Many today think that Jewish persecution started and ended with the Holocaust, but in fact, the Holocaust was a culmination of centuries, even millennia, of expulsions, massacres, discrimination, and religious intolerance. Unfortunately, October 7th, 2023, is just another episode in that long, tragic history.

On Jewish Victimhood

ZB: Would you say that Jews, in particular, have had a more tumultuous and difficult history than other groups of people?

DB: I’m always hesitant to make those kinds of comparisons because it can feel like what some people call a “victim Olympics.” There’s no shortage of injustice in the world, and many groups have suffered. Antisemitism is often referred to as “the longest hatred” because Jews have been around for so long. But I wouldn’t want to make any claims about being unique or the most severe. The focus should be on recognising all forms of hatred and opposing them.

ZB: It is strange though, don’t you think? Jews have been around for a long time, but so have Zoroastrians, for example. They’ve faced persecution too, and they still practise in places like Iran, India, and Pakistan. Why is it that Jews, such a small minority, have such a significant influence today?

DB: That’s the big question, and historians have struggled to answer it for a long time. It’s somewhat inexplicable. You don’t even need Jews to be present in a country for antisemitism to arise. There are places, both in history and today, where there are no Jews, yet antisemitism still exists. It mutates and adapts to different environments, which makes it difficult to explain why it persists in so many forms.

ZB: And why should non-Jews care about antisemitism?

DB: For the same reason everyone should care about any form of discrimination. Even if you aren’t personally affected by racism, sexism, or antisemitism, the fact that others are being maimed, tortured, or even killed because of their identity should concern us all. At that level of targeted violence, we all have a responsibility to care.

Israel and Utilitarianism

ZB: I’m not sure if you describe yourself as a negative utilitarian, but many people do. How do you feel about that label?

DB: I’m not a negative utilitarian. I’ve been described as one, but I don’t subscribe to it. Some of my views align with negative utilitarianism, but none of my arguments are predicated on that theory.

ZB: In terms of your views on antinatalism and veganism, you seem to care more about minimising suffering than maximising happiness. With that in mind, my question is: Do you believe that the creation of Israel in the Middle East has, in the grand scheme of things, created more suffering?

DB: Let’s clarify something first. If my focus were only on minimising suffering, then yes, I would be a negative utilitarian. However, I do think there’s an asymmetry between bad things and good things, which means that avoiding bad things should take some priority, but that doesn’t mean trade-offs are never justified. We make trade-offs all the time, and they can be reasonable. When it comes to grand historical events like the creation of Israel, it’s hard to say what the counterfactual would have been. Some argue that more suffering was caused by its creation, but Jews were without a state for 2,000 years and that certainly didn’t result in less suffering for them.

On Ethnostates

ZB: Do you think it’s ethical to have a state that is meant for a specific ethnic, cultural, or religious group?

DB: There are inherent challenges with that kind of state, particularly if it results in second-class citizenship for those outside the favoured group. However, many countries, especially liberal democracies, accommodate ethnic or cultural majorities without infringing on the civil rights of minorities. Take Italy, for example. If you’re a Catholic, the calendar is set to accommodate you. That is not the case if you’re Muslim or Jewish. However, that is acceptable, as long as your rights are protected. The key is ensuring that minorities aren’t treated as second-class citizens. In some cases, when large groups can’t coexist peacefully, partitioning a country—like Yugoslavia—into smaller, self-governing entities is a solution, provided minorities in those entities are still granted full rights.

Does Israel Matter?

ZB: Do you think the future of Israel is an important issue that the world should care about?

DB: I do. For several reasons. One is that Israel is a substantially liberal democracy, even though it’s not perfect—no society is. Liberal democracies are the kinds of places people flee to; they’re not the places people try to escape from. So, having more liberal democracies is generally a good thing. If Israel were to vanish, it’s highly unlikely that the space it occupies would be filled by another liberal democracy. We don’t see evidence of that happening in the region. So, when people call for “a free Palestine from the river to the sea,” it might sound like a nice slogan, but we need to ask what that would actually look like. Chances are, it would look a lot like Gaza before October 7th, or the West Bank, or Jordan, or Egypt—places that are far from liberal democracies.

ZB: Is there an argument that we’re looking at this issue through a Western lens, and that perhaps some cultures don’t want to live in a liberal democracy?

DB: I don’t believe that’s true, because many people from non-Western countries are trying to move to Western democracies precisely because they want the freedoms and opportunities these places offer. Now, while some migration is possible, it’s not feasible for everyone living under repressive regimes to relocate. After all, these regimes often have the largest populations. So, it would be much better if those states became free, and I think that’s what most people in those countries want. It’s usually the elites in power who resist change, not the general population.

ZB: In general, what do you think is the best way to encourage illiberal nations to become more liberal and democratic?

DB: That’s a very difficult challenge, and in many cases, it might even be impossible. Invading these countries to force regime change isn’t the solution. We saw that when the US invaded Iraq. The goal was to bring about democracy, but instead, it made things worse in many ways. The same would likely happen if the West tried to invade North Korea or China. What we should do is support the liberal elements within those societies and try to coax them along, but real change is not something that can easily be imposed.

On South African–Israeli Relations

ZB: Would you consider South Africa a liberal democracy?

DB: In name, yes. Since 1994, South Africa has had a liberal constitution, and it is a democracy—everyone is allowed to vote. However, that doesn’t mean minorities aren’t sometimes treated differently from the majority, and there are plenty of imperfections. But for now, South Africa remains a liberal democracy. I’m not sure what direction it’s heading, though.

ZB: How would you describe South Africa’s relationship with Israel?

DB: It’s quite poor at the moment. Earlier this year, South Africa formed a government of national unity, but the African National Congress (ANC) still controls the international relations department. And their stance on Israel hasn’t changed much. The relationship is extremely one-sided and unhelpful. South Africa likes to hold itself up as a model for peaceful transition and believes it can export that model elsewhere, but they overlook many of the differences between the South African situation and the Middle East. If they were more of an honest broker, they could potentially play a helpful role.

ZB: Israel is often compared to apartheid South Africa. What’s your view on that?

DB: A lot of work has been done examining that comparison. Within Israel’s pre-1967 borders, the apartheid analogy is utterly false. However, the situation in the West Bank is more complex. There, you have Israeli citizens who enjoy the full rights of citizenship, but they live alongside Palestinians who don’t have those same rights. East Jerusalem is even more complicated, where Palestinians were offered citizenship, but many declined. Gaza, after Israel’s withdrawal, is a completely separate case, where Palestinians could have established their own state but chose not to.

When Is Violence Justified?

ZB: Is any violence toward Israel justified or ethical? When is it acceptable to use violence?

DB: That’s a very big question, and I don’t think I can answer it easily here. However, I don’t believe that Palestinian rejection of Israel provides a basis for violence. I don’t want to suggest that all the blame lies on one side. In one of my earlier articles for Quillette, I explored how both sides react to each other, often inappropriately. People are complicated—they overreact, they misunderstand, they act out of fear. So blame doesn’t fall solely on one side. That said, I think more of the blame rests with those who reject the idea of Jews having a state in a part of mandatory Palestine. There have been multiple offers for a Palestinian state, all of which have been rejected. This undermines the justification for violent resistance.

On the Zionist Taboo

ZB: Would you say being pro-Israel is one of the biggest taboos in academia?

DB: Yes, especially right now. It’s increasingly difficult to be a Zionist or openly defend Israel, particularly in the Anglophone world. In some places, like South Africa, it’s even harder. But even in the US, there are risks to declaring yourself a Zionist or even being identified as Jewish on campus.

ZB: Is there anything else you’d like to say about Israel or the anniversary of October 7th?

DB: It’s hard to condense my thoughts because there’s so much to say. One thing that stands out to me is how, in a conflict between a liberal democracy and a repressive theocracy, people in the West often find themselves sympathising with the theocracy. It’s one thing to criticise flaws on both sides—there’s always room for that. But if you look at any conflict, even the one between the Allies and the Nazis in World War II, you’ll find things the Allies did wrong. Yet, if your conclusion from that is to support the Nazis, you’ve completely lost the plot. And I think that’s what’s happening here. Balanced and appropriate criticism of Israel is perfectly fine, but when people end up supporting regimes like those opposing Israel, it’s a sign of moral bankruptcy.

ZB: A lot of this seems to come down to ideology. Many people, especially younger generations, root for whoever they see as the underdog, regardless of the complexities involved.

DB: Yes, that kind of simplistic thinking is prevalent. There are also complexities around who we define as the underdog. It’s easy to see the Palestinians as the underdog because they lack military power. They rarely succeed in causing damage to Israel, which is why October 7th stands out as a rare “success” for them. But if you look at the broader historical picture, the Jewish people have faced repeated attempts to exterminate them, convert them, persecute them, and treat them as second-class citizens. After 2,000 years, they finally get a state, so you can understand why they hold on to it. That doesn’t mean there are no limits to what they can do to protect themselves—there are constraints, and those constraints must be respected.

ZB: Are they respecting those constraints?

DB: That’s a hard question to answer. One of the points I’ve made in my Quillette articles and elsewhere is that determining whether an action in war is proportionate requires a lot of information—information that only military commanders and legal advisors in the IDF have. These decisions are often approved or disapproved by legal teams based on specific data. Critics abroad don’t have access to this level of detail, so it’s dangerous to jump to conclusions about whether actions are disproportionate. And it’s certainly misleading to judge based on casualty numbers alone. War doesn’t work that way.

ZB: Beyond the legality of war, as a philosopher, can you explain why it’s problematic to view this conflict purely in terms of the number of deaths on each side?

DB: In any war, one side will typically suffer more losses than the other. Civilians often bear the brunt of the casualties, which many people don’t realise. So, simply tallying deaths to determine who is in the wrong is a flawed approach. Think about World War II—if we had stopped fighting the Nazis after a certain number of their casualties, we would have allowed them to regroup, ultimately rendering the lives lost up to that point meaningless. You can’t base your judgment of proportionality on casualty numbers alone. Instead, it’s about whether the strategic importance of an action justifies the harm done to non-combatants. That’s how the morality of war works.

On Religion

ZB: How much of a role does religion play in this conflict?

DB: Religion plays a significant role, particularly on the Palestinian side. There’s a higher level of secularism among Israelis, although that’s changing with demographic shifts. There’s a religious Right in Israel, and their aspirations for the entirety of the historical land of Israel complicate the possibility of a Palestinian state. That creates ongoing conflict. But it’s important to note that Israel has made peace offers in the past, even under right-wing governments. For example, Menachem Begin gave back the Sinai to Egypt in exchange for peace, and Ariel Sharon withdrew from Gaza, providing an opportunity for peace there. So, the right in Israel hasn’t always been opposed to compromise. However, events like October 7th have only emboldened the Israeli right, as more Israelis come to believe that coexistence is impossible with those who carry out such attacks.

ZB: Polls have shown that both Israelis and diaspora Jews have moved more to the right since October 7th.

ZB: How do we share land when different groups hold such radically different ethical frameworks? For example, Islam might have a different ethical framework than Buddhism, Christianity, or Judaism. How do we decide which ethical framework is the right one?

DB: I wouldn’t want to stereotype Islam or assume all Muslims think alike—that would be prejudicial. But I do think that, at present, it’s not possible to have a single state between the river and the sea, given the divergent cultures and mentalities. Even the Palestinian Authority and Hamas struggle to work together. This has led some people to suggest that perhaps we need a three-state solution, though that may be a cynical view. Division of the land seems to be the most viable path forward at the moment, but even that isn’t easily achieved. The events of October 7th have only set back the cause of peace. That said, I don’t want to rule out the possibility that, in the long term, with trust-building and good faith on both sides, two states could live side by side with different cultures but still coexist peacefully. Look at Germany and France—they were bitter enemies for centuries, and now they get along quite well. History brings change, though it often requires a lot of hard work to make that change happen.

ZB: Do you believe there’s a universal ethical framework that all humans can live by, regardless of culture or religion?

DB: That’s a complicated question. When you say “universal,” do you mean one that’s accepted universally or one that applies universally? Because there’s clearly no ethical framework that’s accepted by everyone. People have deep disagreements. But just because there’s disagreement doesn’t mean everyone is equally right. If one society believes slavery is acceptable and another believes it’s wrong, both can’t be correct. We have to evaluate these beliefs case by case. It’s unlikely that everything in Western societies is right and everything in other societies is wrong, or vice versa. There are valuable practices and ideas in many cultures, and we should try to emulate what’s good. It’s about learning from one another, not thinking in terms of “the side of the angels” versus “the side of the devils.”

ZB: Would you define “good” as minimising suffering and maximising happiness?

DB: That’s the view a utilitarian would take, but I think it’s more complicated than that. And it’s probably more complicated than we can get into with the time we have.

On David’s New Book, Very Practical Ethics

ZB: Maybe you’d like to talk a bit about your latest book, Very Practical Ethics? Unfortunately, I haven’t had the chance to read it yet.

DB: No problem! I assumed you wouldn’t have had the chance. The book addresses ethical problems that ordinary people encounter in their everyday lives. Historically, practical ethics has focused on life-and-death decisions or public policy issues, like whether the death penalty should be legal or whether abortion is moral. These are important issues, but they don’t come up frequently in most people’s lives. In this book, I wanted to look at the ethical challenges people face regularly.

ZB: Yeah, so the chapters are on topics like sex, the environment, smoking, giving aid, consuming animals, language, humour, bullshit, and forgiveness. I’m particularly curious about the chapter on bullshit. What’s that about?

DB: There’s been some philosophical literature on what constitutes “bullshit.” Although I touch on that, my chapter mainly focuses on the ethical aspects of bullshit. Is it ever morally acceptable to engage in bullshit? And what should we do about other people’s bullshit? Should we call them out regularly, or should we just ignore it? The problem is that bullshit is pervasive—there’s so much of it. There are ethical issues surrounding both producing it and responding to it.

ZB: By bullshit, do you mean lying?

DB: No, it’s not the same as lying. Harry Frankfurt, who wrote a very influential book On Bullshit, distinguishes between lying and bullshit. Lying is when you know what the truth is and say something false. Bullshit, on the other hand, is when you speak without concern for whether what you’re saying is true or not. You’re indifferent to the truth. Then there’s also a different kind of bullshit, identified by the philosopher G.A. Cohen, which you often find in universities—where people use flowery language to say very little or nothing at all. It’s all about appearances with no substance, what Professor Cohen calls “unclarifiable unclarity.” So, it’s quite different from lying.

Life is filled with many different practices—people have sex, they joke, they bullshit, they seek forgiveness. All of these things deserve ethical scrutiny, and that’s what I try to explore in the book. I often have unconventional or unusual combinations of views, so I encourage people to read it and come to their own conclusions. The chapters can be read in any order, as they are mostly freestanding. There’s an introduction and conclusion that tie everything together, but each chapter addresses a specific ethical issue on its own.

ZB: Are you still thinking a lot about antinatalism, or has another ethical issue taken up more of your attention recently?

DB: I think about many different issues. While people often want me to discuss antinatalism, that’s not the only topic I’m focused on. This book is an example of my broader range of interests. That said, antinatalists will find some connections to their concerns in parts of the book. For instance, in the chapter on the environment, I discuss how population growth contributes to environmental problems, which is something antinatalists are concerned about. So, even if the book isn’t directly about antinatalism, there are threads of it woven through.

ZB: It doesn’t look like Israel or antisemitism come up much in the book?

DB: They do, actually. For example, when I talk about language and how people become sensitive to certain terms, I sometimes use Jews as an example. I also use other examples, but there are references to Jews and antisemitism in the discussion of humour ethics. I touch on how certain groups, including Jews, women, and racial minorities, are often the focus of heightened sensitivity around language.

ZB: I’m looking forward to reading it. Where can people get a copy?

DB: It’s available through Oxford University Press, and you can also find it on Amazon. If bookstores don’t have it in stock, they should be able to order it.

ZB: I prefer secondhand bookstores myself.

DB: Me too, although my book might not make it to those shelves just yet.

How Did David Discover Quillette?

ZB: (laughs) So, how did you first come across Quillette?

DB: I can’t remember exactly. It was probably through word of mouth. My first piece for Quillette was several years ago, but I had heard of it well before that.

ZB: I believe your first piece was “Going South: Life at the World’s Most Progressive University.”

DB: Yes, but where “progressive” should be in scare quotes.

ZB: (laughs) I might have to edit that in! That piece was about the University of Cape Town. Are you still there?

DB: No, I’ve recently retired.

ZB: Well, thank you so much for joining me today, David.

DB: My pleasure. Thanks for having me. Have a good day.

ZB: You too. Goodbye.