Education

Going South: Life at the World’s Most Progressive University

Activists have discovered that the best form of defence is attack.

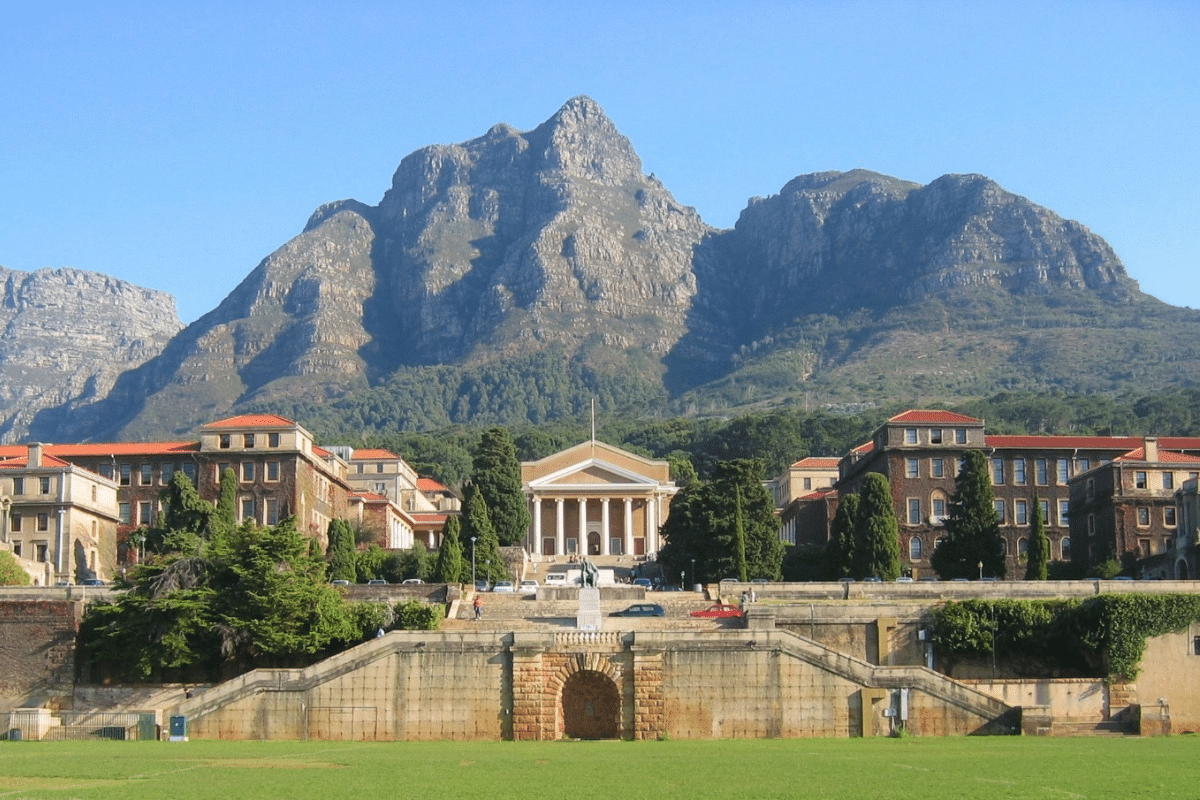

Many universities have a problem—on this point there seems to be widespread agreement. The nature of that problem, however, remains bitterly contested. Liberals and conservatives worry that higher education has succumbed to regressive radicalism on matters related to race and gender. Those who self-identify as progressives and social justice activists, on the other hand, complain that universities are still governed by embedded structures of oppression, and that liberals and conservatives have succumbed to a moral panic in response to reasonable calls for reform. Although these debates are common in universities in countries like the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, they are particularly pronounced in South Africa, where I teach philosophy at the University of Cape Town.

In my book, The Fall of the University of Cape Town, I offer a detailed account of what has been happening at (and to) Africa’s leading university since the #FeesMustFall protests began in October 2015. On multiple occasions in 2015, 2016, and 2017, the university was shut down for weeks at a time by a relatively small group of activist students demanding “decolonized” higher education and an end to increases in student fees. In ostensible pursuit of these goals, protesters set fire to historic artworks, university vehicles, and the vice-chancellor’s office, and vandalized university buildings with human excrement.

More worrying still, they intimidated hundreds of people with threats of violence backed by instances of assault. An activist used a sjambok to whip a cellphone out of a fellow student’s hand, a vice-chancellor was punched, students and staff who defied the protesters were pushed and shoved, a security guard was beaten with a steel rod, and another had to be hospitalized after a rock was dropped onto his head. No one was ultimately held accountable, either by the university’s disciplinary system or in the country’s courts. (When charges were laid, they were later withdrawn.)

Furthermore, the behavior of activists indicates that racial abuse is now compatible with the pursuit of social justice, so long as the recipients of such abuse are either pale-skinned and/or insufficiently progressive in their politics. One student protester wore a t-shirt bearing the phrase “Kill All Whites”; a memorial to soldiers killed in both World Wars was daubed with the words “Fuck White People”; a senior academic who referred to a junior colleague as “just another fucking white woman” was appointed to a senior administrative position shortly thereafter. Darker-skinned students and faculty, meanwhile, who do not toe the party line, have been denounced as a “coconuts,” “sell-outs,” “colonial administrators,” and “porch negroes.”

On July 27th, 2018, Professor Bongani Mayosi, Dean of the UCT Faculty of Health Sciences, committed suicide after he was persecuted by activists disrupting the campus. Professor Mayosi’s sister did not hesitate to hold the #FeesMustFall protesters morally responsible for this tragedy. “He was hardly two weeks in his new position and the protests broke out,” she told the Sunday Times. “The vitriolic nature of the students and their do or die attitude vandalised his soul and unravelled him. Their personal insults and abuse cut him to the core, were offensive to his values and were the opposite of everything he was about.”

This kind of bullying has become pervasive, and some of it comes from the top down. In 2020, Zetu Makamandela-Mguqulwa, the university ombud, reported that she had received 37 complaints of bullying by the Vice-Chancellor, Mamokgethi Phakeng. When the university’s governing council tried to suppress her report, she published it on the ombud website and criticized the council for failing to address the VC’s conduct. She was then summoned to meet the chair of the council to answer unspecified charges of “misconduct.”

Other instances of bullying, however, come from the bottom up—when vexatious charges of racism are made against faculty by unscrupulous students bent on getting their own way. Still other instances of bullying are peer to peer. But bullying in any direction is invariably justified with reference to the persecutor’s membership of a historically “oppressed” group, even when their victim is also a member. That is why a black female vice-chancellor can accuse a black female ombud of participating in racist machinations against her.

The ubiquitous accusations of racism are almost always groundless, but in the prevailing climate, they receive immense traction and have contributed to a significant chilling effect on freedom of expression. A number of the artworks that survived the bonfires have since been removed from display. In some classes, students are expected to regurgitate the mal mots fed to them by activist academics. In one such case, a lecturer posed the following exam question: “Write detailed notes on race and racism. In your answer take care to specify the reasons for the impossibility of friendship between blacks and whites.”

Those who balk at such sentiments run the risk of public vilification. Even the university’s Academic Freedom Committee has been compromised. When Flemming Rose, the magazine editor who published the Danish cartoons of Mohammed in 2005, was invited to deliver the 2016 academic freedom lecture at UCT, he was disinvited by the university executive. The Academic Freedom Committee was then reconstituted, and some of those subsequently invited to deliver the annual academic freedom lecture have been opponents of freedom of expression.

It should not be surprising that radicalism is flourishing at South African universities. In other parts of the world, broader social forces and norms provide a counterweight to activist excesses on campus. But there is no such counterweight in South Africa. Despite a largely liberal constitution, the African National Congress—the party in power since 1994—remains unsympathetic to the West, which it continues to associate with historical colonialism. Its sympathies lie, instead, with various repressive states and their Third-Worldist rhetoric. (The contrast between scathing criticism of liberal democracies and the free pass offered to authoritarian regimes and political movements is a hallmark of postcolonial theory.)

Moreover, the country’s national narrative is committed to “decolonization” and “transformation”—buzzwords selectively and inconsistently employed by sloganeers in defence of the radical change they demand. We are told, for example, that university curricula—not only in the humanities, but also in medicine and science—must be “decolonized” and “transformed.” Yet nobody is calling for the “decolonization” of the Western clothes that most South Africans wear, or the abandonment of Christianity, a colonial import and still the most popular religion in South Africa.

Post-apartheid South Africa remains obsessed with race. Technically, nobody is racially classified by the state any longer, but the implementation of extensive racial preference legislation presupposes continued acceptance of those categories. So, while people are not officially categorized by race, they are in practice, sometimes against their will. Racial preferences in South Africa have acquired two distinctive features that distinguish them from the forms of affirmative action common in, for example, North America.

First, racial preferences in South Africa are much stronger. Many of the racial preference policies and practices permissible in South Africa, such as quotas, would be illegal in the US or Canada. Some of the racial preferences practised in South African universities may even be illegal under South African law, but are sufficiently covert to avoid legal challenge.

Second, the beneficiaries of South African racial preferences constitute a large majority of the population and of students at the University of Cape Town. Blacks are not yet a majority of the academic staff, but it was always going to be difficult to get the demographics of the professoriate to reflect the demographics of the country after hundreds of years of anti-black racism. This has become an even more challenging task because the quality of primary and secondary schooling has declined since the advent of democracy.

Although all South African universities operate within this context, the effect on the University of Cape Town may be more extreme than on others as a result of decisions taken by this university’s leadership during the unrest from 2015 to 2017. Whereas other leading universities in the country took a stand against criminality, the leadership at the University of Cape Town pandered and capitulated to it. This has only emboldened protesters and set the tone for what has unfolded since.

Consequently, activists have discovered that the best form of defence is attack. Even Professor Mayosi’s suicide was not enough to provoke reflection or self-criticism. In the wake of his death and the remarks from his grieving sister about protesters’ culpability, activists attempted to repurpose Professor Mayosi’s death for their own political ends. In an article for the Daily Maverick, Lydia Cairncross called for “deep thinking, open feeling and collective healing,” but went on to indict what she called “the insidious, covert racism that permeates so many of our university structures, both in the bureaucracy and the academic leadership” and “the inevitable stress caused by working within a higher education system built within a broader society which is inherently unjust.”

Activists, it turned out, were incapable of the accountability they demanded of others. “The occupation of the Health Sciences deanery in 2016,” she wrote, “marks, for me, a transformative moment in our history as a faculty. Seldom have I seen political protest unfold so spontaneously, so respectfully, so democratically, so beautifully as that particular protest did.” If the protesters were guilty of anything, she concluded, it was of failing to push hard enough for change:

Let us not absolve the institution of the university; let us not absolve our pathological work culture; let us not absolve overt and covert racism at UCT and in our society; let us not absolve the capitalist system that makes of our thinking and our students, commodities to be bought, sold and measured. And, finally, let us not absolve ourselves for not changing this system, for not taking care of ourselves and for not taking care of each other.

In an article at Politicsweb, an activist named Chumani Maxwele, who initiated the #RhodesMustFall protest, made the same arguments with greater frankness. He acknowledged that Professor Mayosi had been called “a coconut and a sellout,” but declared it irrelevant since many black academics had been called names “in the heat of political debates.” The real blame, he said, lay with the university.

It may be that the University of Cape Town only seems more extreme because I am seeing it up close. My book offers a detailed account of what has happened here so that others can compare my experience with their own. Those comparisons will be illuminating. I am, however, convinced that concerns about a conservative and liberal moral panic at UCT are misplaced. Such accusations are used to dodge moral responsibility and to justify cruelty, violence, and vandalism in the name of self-righteous indignation.