Claire Lehmann

Architecture as Revenge—Charlotte Allen

Charlotte Allen’s critical review of The Brutalist is one of my favourite essays of the year, deftly describing Brutalist architecture as a “visual punishment, deliberately inflicted on its viewers for their sins.” She grants Brady Corbet’s film its due as a visual achievement, beautifully shot in resurrected VistaVision, while showing how its central character is deeply unlikeable and its portrait of mid-century America crude and ungenerous. Allen’s essay is itself a model of sharp, historically informed cultural criticism.

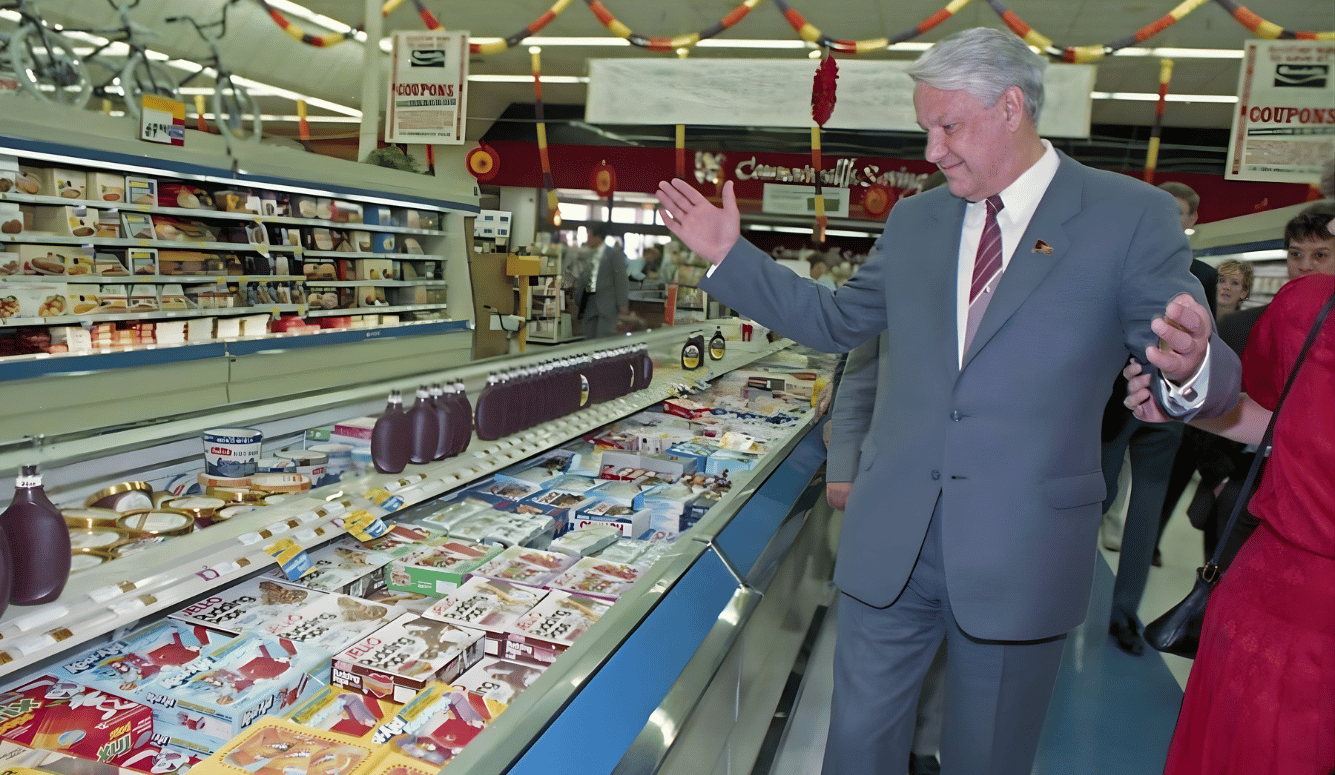

The Ingratitude of the Well-Fed—Maarten Boudry

Maarten Boudry is an atheist who has written an essay that gets at the spiritual problem of our times: the ingratitude we have for modern civilisation. He examines the spoiled attitudes of those who attack capitalism and liberalism without grasping the progress these systems have delivered, and shows how material abundance breeds forgetfulness rather than appreciation. The essay is a clear-eyed defence of modernity, and a reminder to reflect on civilisation’s hard won achievements.

“Nothing Is to Be Feared. Everything Is to Be Understood.”—An interview with Peggy Sastre—Claire Lehmann

Peggy Sastre’s interview with Quillette is my final choice for 2025. Rarely is a thinker able to dissect the philosophical meta-narratives shaping our culture with such clarity and intellectual fearlessness. Drawing on evolutionary biology, feminism, and a deep scepticism of moral panic, Sastre speaks plainly about sex, power, and human nature. The result is a serious conversation that refuses sentimentality and insists on understanding rather than consolation.

Jamie Palmer

The Fugitive Mind—Joan Maltese (includes audio version 🎧)

I have to admit that when I opened this submission at the end of a long day and discovered that it was 13,000 words about mental illness, my heart sank. Since it was already 1 am, I decided to read the first few paragraphs just to get a sense of the thing before I went to bed. Instead, I burned through the whole thing in a sitting. In vivid prose, Maltese relates how she watched her best friend’s life and promising literary career disintegrate into chaos and paranoia. Written with verve, honesty, and disarming wit, her essay is a sad but mesmerising read. Don’t be put off by the length or the subject matter, this will be an hour well spent.

Sexual Perversity in Ontario—Marilyn Simon

In 2018, a young woman engaged in a consensual sex orgy with five young Canadian sportsmen in an Ontario hotel room and then accused them all of rape. In July of this year, a (female) judge acquitted the defendants of all charges. What makes Marilyn Simon’s account of this incident unusual is her analysis of the complainant’s behaviour, and her broader discussion of the perverse complexities of female desire and arousal: “There are parts of us that want more, and parts of us that want less, and parts of us that are turned on by the things that we don’t want, and so we end up wanting them. These urges can occur at the same time even though they contradict each other. ... We have disordered wills, and part of becoming an adult is realising this.” A sympathetic dissection of psychological complexity and a bracing challenge to the feminist doctrine of consent.

The Worst Racial Slur, In Context—Steve Salerno

This essay was slept on a bit, which is a shame. It’s a warm, matter-of-fact, and refreshingly frank piece of personal writing about the various uses and abuses of a racial slur so inflammatory that most editors won’t print it, and even mentioning the word in a descriptive context can cost a person their job. The author of this essay is white, but this should make no difference to the validity of the points he makes. Sometimes the best way to interrogate an irrational cultural taboo is to violate it with the kind of curiosity and generosity that Salerno displays here.

Jonathan Kay

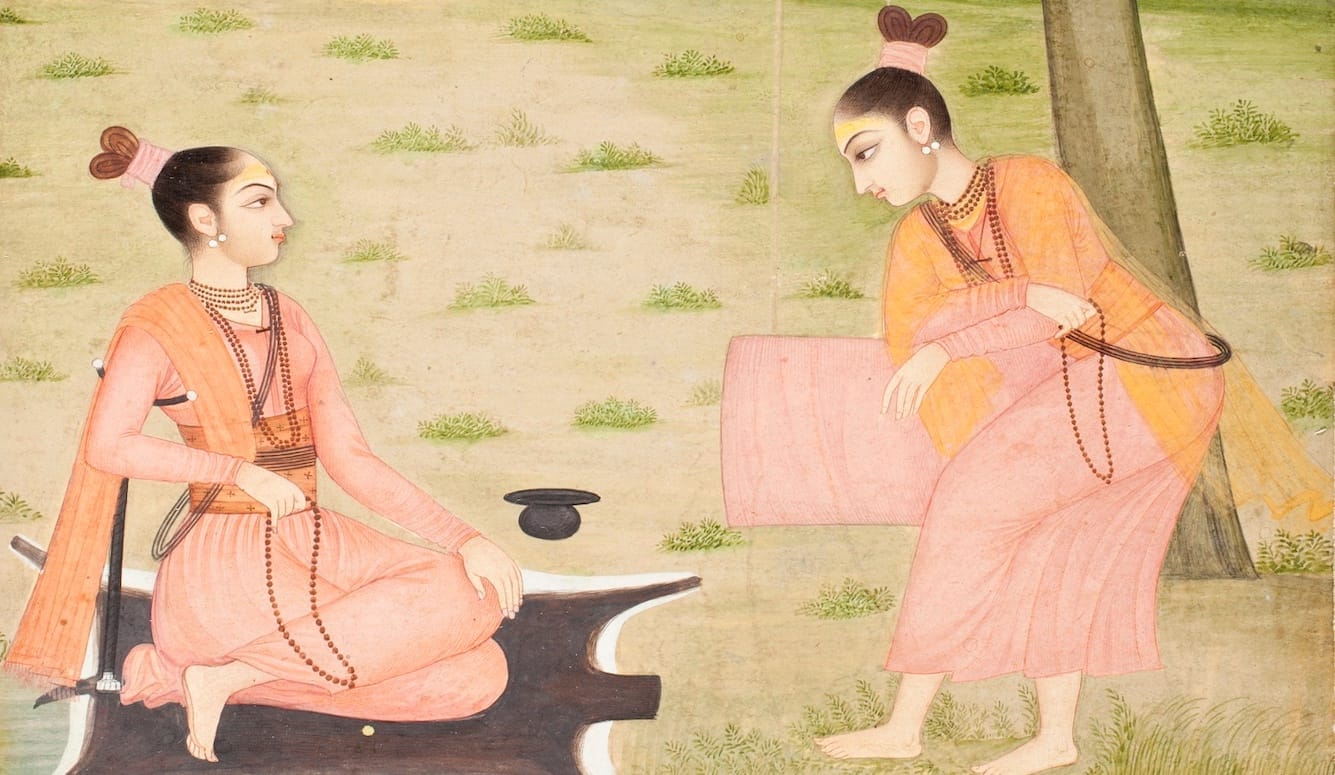

Ancient Indian Tradition—Or Twentieth-Century European Export?—Carl von Siemens (includes audio version 🎧)

Quillette isn’t a scientific journal, and so we don’t usually send articles out for peer review. But when German writer Carl von Siemens submitted a lengthy essay arguing that yoga isn’t really Indian (at least, not entirely), I sent the thing around for expert analysis. Carl practises yoga himself, writes authoritatively, and has even travelled to India to research yoga’s origins. Nevertheless, his thesis that yoga’s mechanics actually originate with European exercise manuals struck me as improbable—and potentially offensive.

But then people in the know started getting back to me. And their feedback aligned with what my own research into Carl’s sources confirmed: Yoga isn’t really the ancient made-in-India institution it’s often billed as. Yes, modern yoga culture owes much to the Indian teachers who’ve perfected the techniques. But many of those techniques were actually invented in twentieth-century Nordic gymnasiums.

Just to be clear, though: Carl doesn’t want you to stop doing yoga: No matter where they were conceptualised, the stretching, muscle-building, and mindfulness exercises associated with yoga are still good for you.

Is the University Of Austin Betraying Its Founding Principles?—Ellie Avishai

I picked this article for two reasons: First, because it’s a great article. And second, because of what its publication says about Quillette itself.

Since its founding, Quillette has stood four-square against the illiberal ideological tendencies that began taking root in progressive academic and cultural subcultures in the 2010s. Now that the political pendulum has begun swinging back in the other direction, many observers wondered (not unreasonably) whether Quillette would remain true to its liberal principles, even if that meant calling out conservatives.

The publication of Ellie’s essay in May, I hope, helped assure our liberal readers that the answer is yes.

Like many American educators, Ellie enlisted with the University of Austin because she had serious concerns about the progressive ideological monoculture and culture of self-censorship she witnessed on other campuses. But once ensconced at UATX (as the start-up school is known), she began noticing signs that “anti-woke” culture warriors can be just as intolerant of dissent as their adversaries.

Universities Are Worth Saving—Jonathan Rauch

In light of all the academic scandals that Quillette has documented over the years, it’s easy to see why some exasperated culture warriors have come to the conclusion that higher education can’t be saved. Jonathan Rauch very much takes the opposite view.

Like it or not, he argues, “the single most important part of the reality-based community is the part where professionals advance knowledge for a living. And that’s universities, research centres, journals, and credentialing organisations.”

“In the liberal spirit,” he concludes, “I would urge that those of us seeking to address the crisis on America’s campuses resist the tendency toward nihilism—the temptation to simply rant about how awful and corrupt academia has become, or to conclude that we need to just (metaphorically) burn it all down.”

Iona Italia

The Feminist, the Filmmaker, and the Führer—Annalisa Zox-Weaver

In the turbulent times in which we live, it’s all too easy to become narrowly focused on politics and, as a result, I sometimes feel that Quillette’s art and culture essays are underappreciated. But they are always among my personal favourites. Zox-Weaver’s intricate portrayal of two glamorous women and their different inabilities to recognise and understand evil is deliciously written. This twin portrait helped me understand both Riefenstahl and Sontag better. It debunks cheap clichés about the nature of fascist aesthetics and illustrates how what the author calls her “hyper-politicisation and aggressive moralism” blinded Sontag to what was most sinister about Riefenstahl’s dishonesty and collusion.

Too Much Monkey Business—Graham Daseler (includes audio version 🎧)

In this detailed account of the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial, Graham Daseler does something that is especially valued here at Quillette: takes a largely unexamined orthodoxy and demonstrates that the truth is both more complicated and more interesting than what is widely believed. As Daseler shows, at its heart, Scopes was not just a battle between religion and science, but a struggle over the limits of academic freedom and over who gets to decide what children are taught: parents, teachers, or the government? Daseler infuses his account with all the narrative suspense and character drama of a classic movie, bringing the protagonists to full and vivid life on the page, while remaining scrupulously true to what can be known about the events concerned.

Have We Forgotten Weimar?—Jay Sophalkalyan

After the horrific massacre at Bondi Beach on 14 December, one of the Australian government’s first actions was to propose new hate speech laws criminalising the expression of antisemitism. It’s an understandable, perennial response born of the belief that we can shape people’s beliefs and actions by controlling what they say. But this strategy has repeatedly failed. Jay Sophalkalyan provides a case study in how and why this happens in this careful, cogently argued account of the counterproductive effects of the Weimar Republic’s speech laws. The attempts to silence Hitler and his followers only added the allure of the forbidden to his appeal. They also created an extensive censorship apparatus that inadvertently silenced his critics and, once the Nazis took power, gifted the Führer with a powerful means of muzzling all opposing voices.

Zoe Booth

The Art of Middle Eastern Pillow Talk—David Christopher Kaufman

This essay struck me because it was so close to home. Since 7 October, I’ve lost a lot of friends, and Kaufman’s candid account of a post-coital conversation about Israel and Gaza captured something uncomfortably familiar: having a close connection with someone while at the same time vehemently disagreeing on a deeply personal issue. This disconnect has been very destabilising for me, so it was comforting to read about someone else going through the same thing.

It resonated enough that it prompted me to interview the author. Deep down, I have an idea that there’s a lot of progress to be made through sleeping with the enemy.

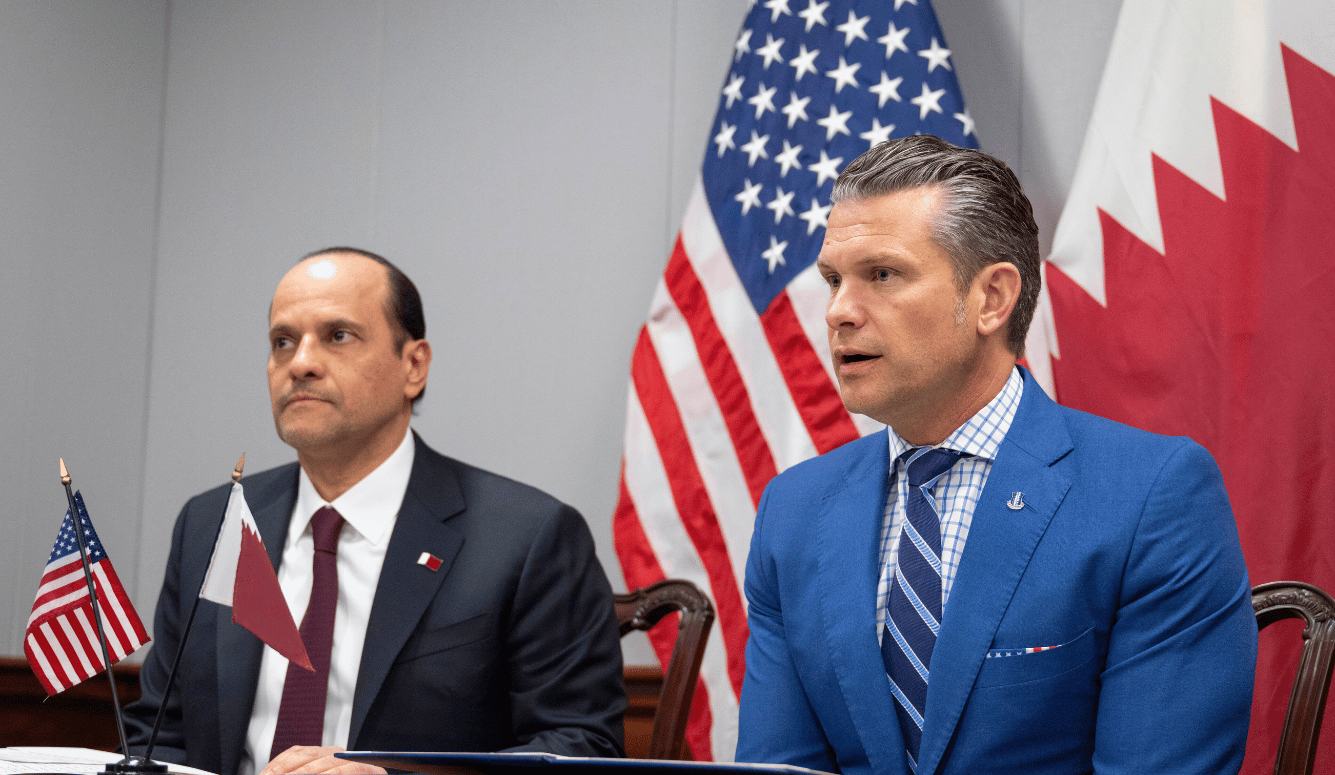

The Qatar Problem: Hamas, Israel, and Saudi Arabia—Chama Mechtaly

Again, this essay stood out enough that it prompted me to interview the author. I was struck by her depth of knowledge of both Jewish and Muslim experience. Chama’s perspective—shaped by life in Morocco and in the Gulf, and her firsthand experience of censorship by Qatar—brought a clarity that’s often missing from discussions of Hamas, Israel, and regional power politics.

When Women Are Radicalised—Claire Lehmann

This essay stood out for its clear-eyed analysis of a trend many of us have witnessed (or, in my case, lived). Lehmann traces the growing ideological divide between young men and young women, with women moving further left. I was most struck by her use of evolutionary psychology to explain the strong pressure within female groups to conform and to signal moral goodness—something that closely mirrors my own experience of becoming radicalised as a young woke woman.

William Barker

Theatre of Blood—Yuki Zeman

The Marquis de Sade by some accounts was a sadistic and perverted loon, but his literary work has its champions. In Sexual Personae, Camille Paglie makes an academic argument for Sade’s significance in the canon. Yuki Zeman’s essay “Theatre of Blood” is a more artistic defence in both content and form. You will want to read Sade’s books after reading Zeman’s essay, despite what you’ve heard about him, if only to see if his work lives up to her incandescent description. Zeman argues that Sade left us a rich and comprehensive saga spanning multiple books, in which our most precious notions about love are crushed by unrelenting and amoral desire.

Making Fiction Boring—Adam Szetela

Have you ever wondered why modern fiction is so boring? Adam Szetela offers a diagnosis in this essay that was extracted and adapted from his recently published book That Book Is Dangerous!: How Moral Panic, Social Media, and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing. The bugs in modern literature’s system are described in the title of Szetela’s book, and they may not surprise you. Szetela describes a process by which the institutions that patronise and publish writers have gradually formed a monolith where what can and can’t be written is the same whoever you ask. Szetela’s essay doesn’t dwell in abstracts but cites case after case that put skin on the bones of this issue.

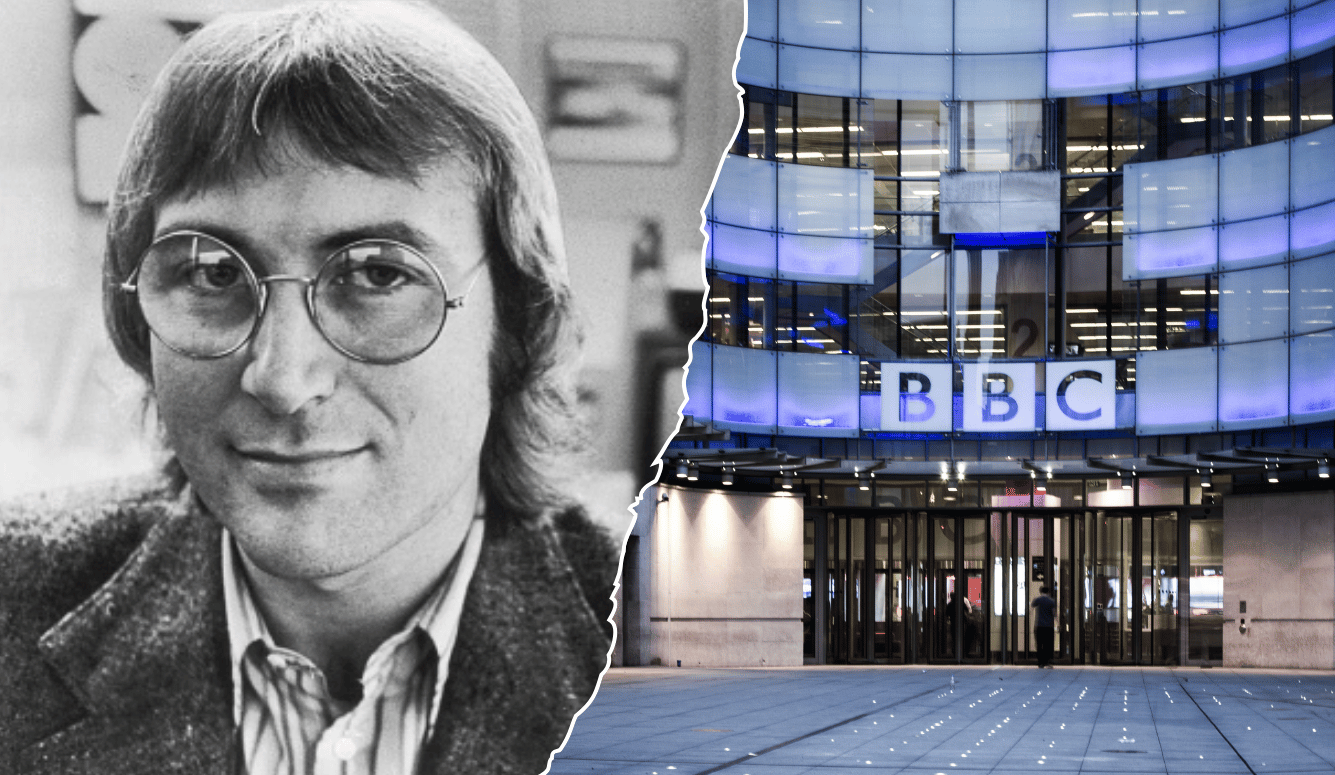

A Journalism of Deception—Graham Majin

Graham Majin’s essay goes far beyond the controversy over bias and dishonesty at the BBC this year. That’s where Majin starts, but he goes further back in time and through the history of both the BBC and of journalism more broadly. His essay is not just a response to the accusations that the BBC has abandoned objective reporting. It is a genealogy of journalistic philosophy that explains the emergence of the belief that a journalist’s job is to report the facts and not try to explain them. Beginning in the Victorian age, Majin works his way down through the decades to the mid 20th century, when a new approach proposed that journalists should explain the news, not just report it. Majin’s essay is both a history and a lesson in journalism’s foundational concepts.