film

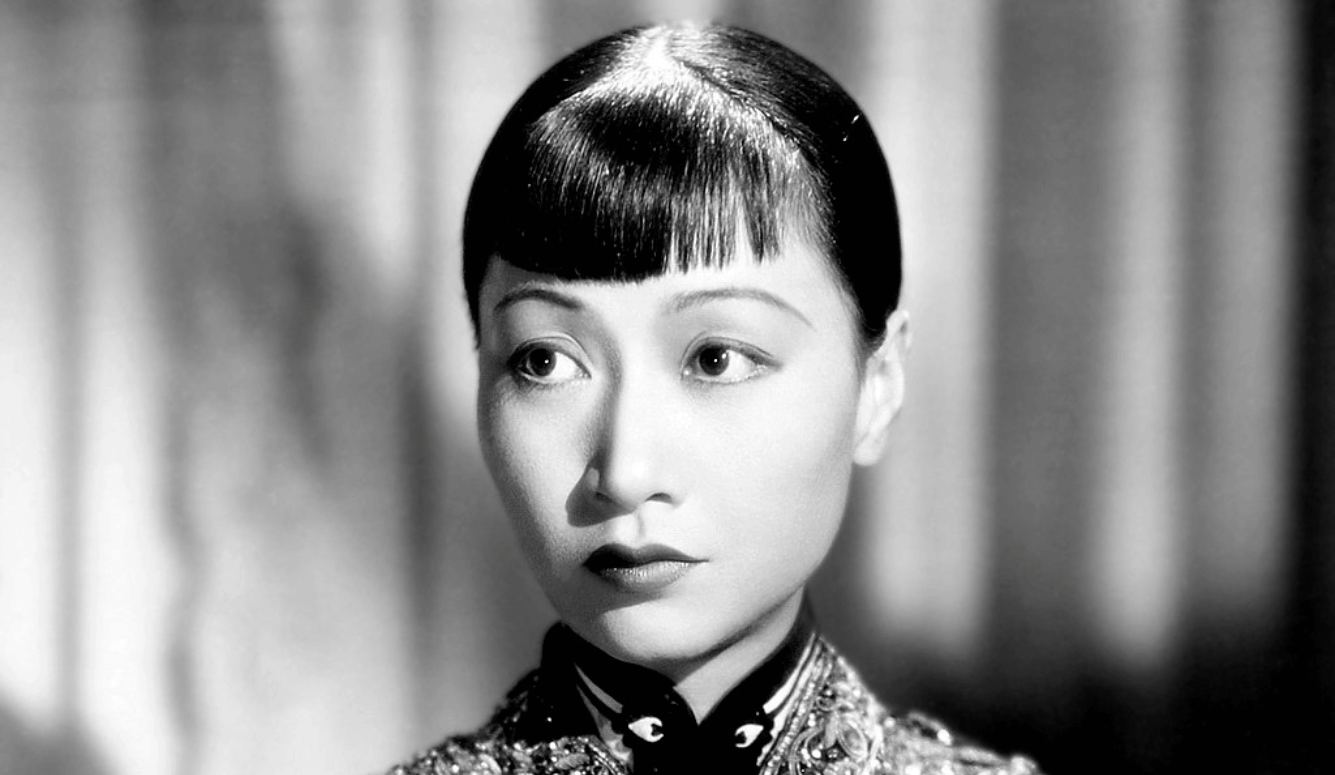

A Perfectly Charming Chinese Girl

Against long odds and in the face of exclusionary casting, Anna May Wong bequeathed us an extraordinary cinematic legacy.

The actress Anna May Wong (1905–61) is enjoying a revival that comes sixty-three years too late to do her any good. The posthumous encomiums include a shelf of popular biographies and deep-dive academic studies—most recently Yunte Huang’s Daughter of the Dragon: Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous with American History (2023); Katie Gee Salisbury’s Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong (2024); and Yimen Wang’s To Be an Actress: Labor and Performance in Anna May Wong’s Cross-Media World (2024)—a knock-off impersonation in Damien Chazelle’s 2022 film Babylon; Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month status; a commemorative quarter dollar; and, in an ironic capstone, a Barbie Doll, a homage that may be too close for comfort to the “China doll” label its model always cringed at. At this year’s Pordenone Silent Film Festival, where several of Wong’s luminous late silent-era star vehicles were screened, she was swooned over as if she were Louise Brooks.

The resurgence is not an instance of ex post facto cinematic affirmative action. During the classical Hollywood era, Wong was the only Asian American actor of either sex whose name got featured billing on ads, one-sheets, and marquees. Today’s identity-centric lens on Hollywood’s past has only magnified her attraction as a vessel to meditate on the “Orientalist” stereotypes she embodied and defied. On looking over Wong’s varied filmography—some sixty films as star, sidekick, and servant, made in France, Germany, Great Britain, and the US—many of her fans lament the lost opportunities in a career stunted by exclusionary casting; others prefer to celebrate the legacy she bequeathed us against long odds.

Wong was born in Los Angeles’s Chinatown in 1905 as Wong Liu Tsong, of Cantonese descent. Her parents operated a laundry, the classic ethnic niche business, but it was the city’s other niche business that beckoned. She ditched school—American lessons during the day, Chinese lessons during the late afternoon—to go to the movies and hang around the location shoots when Hollywood crews descended on Chinatown for Asian atmospherics. The striking young girl in a cheongsam was plucked from the crowd and recruited to stand as a background extra.

Wong’s beauty, poise, smarts, and emotive range soon thrust her into the foreground. She was first showcased to effect in MGM’s Technicolor experiment The Toll of the Sea (1922), part of a rich strain of Jazz Age Hollywood Orientalism that occasionally featured actual Orientals. The Madame Butterfly plotline was already a cliché: a Yankee sea captain shipwrecked in Hong Kong woos, weds, and impregnates the beautiful Chinese girl who rescues him. Things work out fine for him, but not for her. Using the racist lingo that was so much a part of the vernacular that the writer seems unaware of the slur, Variety’s editor-publisher Sime Silverman singled out “the extraordinarily fine playing” of Wong as the “chink wife” of the sea captain. At Billboard, film reviewer Marrion Russell praised the colour registration of the film, which was “so perfect that it seems as if you could put your arm around the waist of the little Chinese girl and actually feel her little plump body.” Wong was just seventeen years old and still working shifts at the family laundry.

Wong’s performance caught the eye of Douglas Fairbanks, the biggest action star in Hollywood, who cast the “charming little Chinese flapper” in his Arabesque fantasy The Thief of Bagdad (1924), where she played a Mongol slave girl in a skimpy outfit that exposed her lithe form. (Fairbanks wrote to her father to assure him there would be no hanky panky on the set.) By then, Wong had “the distinction of being the only Chinese actress who has ever won fame in pictures in America,” marvelled Photoplay in 1924, a line that remained true until the twentieth century.

Fame, however, did not mean better parts. Wong was relegated to Asian or Asian-adjacent roles well below her weight class: a Chinese vamp in the farcical Forty Winks (1925), the Indian princess Tiger Lily in Peter Pan (1925), and an Inuit girl in The Alaskan (1925). As Hollywood’s favourite “ornamental Oriental,” she was little more than set design in incense-suffused hokum such as Mr. Wu (1927), where the lead female role went to French import Renée Adorée, with Wong serving as her faithful handmaiden. Even at the time, the incongruity and injustice of the casting did not go unnoticed. “With a perfectly charming Chinese girl like Anna May Wong not only in pictures but right there on the set, WHY should they give a pretty little plum role like that to Miss Adorée?” protested M.H. Shryock in a letter published in the October 1927 issue of Photoplay.

Fed up with second billing and third-rate treatment, Wong—like Louise Brooks—lit out from Hollywood to seek more challenging parts in Berlin. “They are strong for the exotic here,” explained Claire Trask, Variety’s Berlin stringer. “They would even accept stories with the regular love interest and a happy ending because economic pressure does not cause prejudice against representatives of the yellow race.”

Wong’s European interlude marks the zenith of her screen artistry, a glimpse of what might have been had Hollywood, and America, nurtured her talent. The German director Richard Eichberg, understandably mesmerised, cast her in the lead in a pair of back-to-back melodramas: Show Life (aka Song) (1928), where she is on the receiving end of a knife throwing act; and Pavement Butterfly (1929), where her love for a struggling artist is unrequited, but at least not fatal. An Alfred Eisenstadt photograph from the period shows Wong, at what looks to be a swell party in Weimar Germany, flanked by a jaunty Marlene Dietrich and future Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. She also sat for an interview with a smitten Walter Benjamin. The conversation between the German Jewish philosopher and “the chinoiserie from the Old West” is reimagined in a delightful short film by Yunah Hong, Parlor Game: When Walter Meets Anna May Wong (2025).

Wong’s next film, Piccadilly (1929), shot in London for British International Pictures and directed by Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft (Ufa) maestro A.E. Dupont, is the unquestioned masterpiece in the Wong oeuvre. From the title sequence onward—the credits pass by on the side of a double decker London bus—it plays like a valediction for the genius of silent screen technique before the onset of the sound revolution. The action kicks in when the tuxedoed proprietor of a swank nightclub discovers Wong, a scullery maid, sensuously undulating on a tabletop for the amusement of the kitchen staff and she is soon the featured attraction of the floor show, outfitted in a ludicrous faux Thai-Balinese get-up topped by a golden headdress with a pointed horn. Like Eichberg, Dupont seems besotted with his star; the camera caresses her with adoring close ups and head-to-toe long shots set in relief against the most expensive set yet built in the UK. Unfortunately, by the time Piccadilly was released stateside, with a brief synch sound prologue, the silent screen was yesterday’s medium. “3% dialogue, sound effects and synchronized score,” ads warned.

Wong spoke on screen for the first time in Eichberg’s The Flame of Love (1930), filmed in London, another story of doomed romance which leaves her character lifeless at the end. Like Dietrich in The Blue Angel (1930), she acted in both the English and German language versions of the film, the only member of the cast fluent enough to work a double shift, according to Nerina Shute in the 11 November 1939 edition of Film Weekly—or rather a triple shift: she also performed in the French version. “They were essentially working her like a coolie in a Chinese laundry,” remarks Yunte Huang in Daughter of the Dragon. Even on a soundtrack, Wong was expected to meet racial expectations. “Instead of the high bell-like quality with a slight Orient accent, she has the tone quality of a middle western high school girl,” complains Trask in Variety.

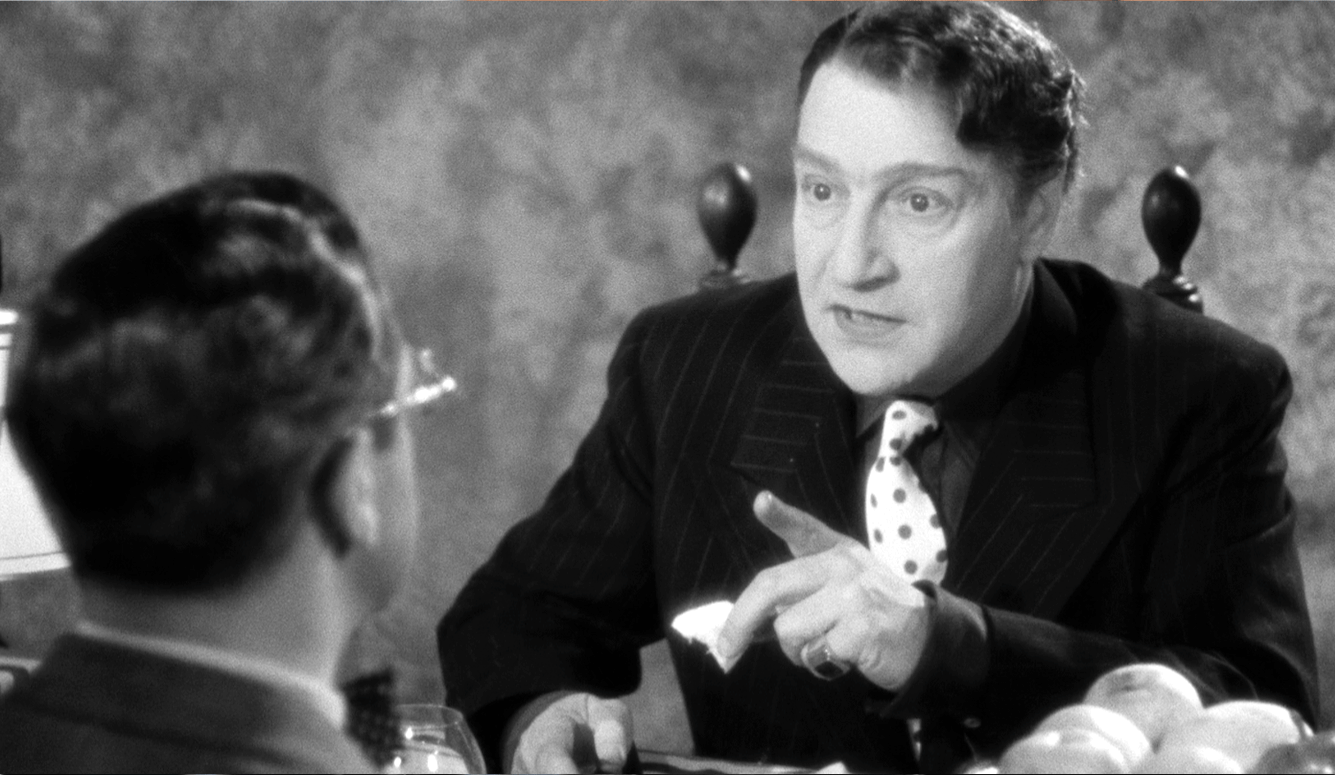

This was 1931, before Hollywood’s Hays Code, under the oversight of industry censor Joseph Breen, prohibited the representation of interracial relationships—but even then Wong was not permitted to so much as kiss a non-Chinese actor on screen. In The Daughter of the Dragon (1931), a loony yellow peril potboiler based on the Sax Rohmer books, she plays the lethally alluring Ling Moy, the daughter of the nefarious claw-fingered Dr Fu Manchu, an arch fiend bent on destroying the Anglo-Occidental empire. She is in love with an English gentleman (Bramwell Fletcher) while a Chinese detective (played by Japanese actor Sesue Hayakawa) is in love with her. Yet neither suitor kisses more than her hand. “The never-the-twain-shall-meet rule is enforced to the letter,” the Hollywood Reporter noted, even though the other character in question was Chinese. But happily, the pre-Code period also made room for her best supporting role, paired with her Weimar pal Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1932), an interracial buddy film set in Paramount’s version of war-torn China. On the Criterion box set, Dietrich & von Sternberg in Hollywood, film critic Imogen Sara Smith wryly voices disappointment at the film’s unlikely heteronormative closure in which Dietrich’s sultry adventuress winds up with a stuffy British officer instead of ending with the two sisters under the silk riding off together to seduce and scam Chinese warlords and Christian missionaries.

Throughout her career, sympathetic critics monitored Wong’s blinkered options and pleaded her case. After “seeing one Chinese part after another going to ‘white’ movie gals while she waited hopeless,” Wong “had to go to Europe before she gained honor in her own country,” wrote her friend and fan Rob Wagner, editor-publisher of Script, on 1 September 1934. Wagner begged Hollywood producers to feature her in parts worthy of “her brains and fine artistry” but “always that old squawk about ‘race prejudice’” blocked her path, a prejudice, Wagner felt, that “exists mostly in [the producers’] own minds.”

Actually, the race prejudice existed in the letter of American law, where interracial marriages were forbidden by state statute, and in the Hollywood Production Code, whose infamous “miscegenation clause” forbade its representation on screen. Inserted into the Code at the insistence of Jim Crow exhibitors, the “miscegenation clause” specifically proscribed only “sex relations between the white and black races,” but the taboo extended in a racist penumbra to other kinds of “miscegenetic unions” including “in most cases sex union between the white and yellow races.” Wong might arouse desire in white male viewers and the camera eye might linger over her figure, but an end-reel clinch with a white man was taboo. Most of Wong’s films showcase her in a slinky orientalist costume, baring her midriff and thighs, swaying to a pseudo-Chinese melody, but pre- or post-Code, she almost always dies, and often by her own hand—whether by drowning, poisoning, knifing, or shooting—as if by way of atonement for the erotic desire she incites in the white spectator.

After the Code began to be rigidly enforced from 1934, Wong’s options got even more restricted. Like Rob Wagner in Script, Irving Hoffman, the columnist for the Hollywood Reporter, berated the industry for ignoring the “orientalented” actress under its nose. In 1937, Hoffman counted five Chinese-themed pictures in which white actresses were cast in the lead while Wong waited by the phone. In public, Wong tried to shrug it off. Asked by the Hollywood Reporter in March 1937 whether she was being considered for a forthcoming Chinese-set melodrama, she quipped, “No, the producer said I wasn’t the type—I look too Jewish!”

But the exclusionary actions by the studios must have stung—and perhaps none more so than her rejection for the role she was born to play, that of O-lan, the long-suffering wife and mother in The Good Earth (1937), MGM’s big budget adaptation of Pearl Bucks’s 1931 novel, a story of a plucky female protagonist whose will to power overcomes all hardships, propelling her mate Wang Lung (played in the film by ethnic chameleon Paul Muni) from the rice fields to the big house. Viennese-born actress Luise Rainer got the part and won the Best Actress Oscar. As compensation, Wong was offered the second female lead of Lotus, the concubine who supplants O-lan in her husband’s bed, but she refused to play yet another “sexotic” temptress. Besides, she confided to reporter Margaret Kam of the Honolulu Star Advertiser, “she did not relish the idea of playing a part in a real Chinese story surrounded by a Caucasian cast.” (The role of Lotus went to Tilly Losch, another Vienna-born actress.)

Following the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in September 1937, Wong increasingly devoted herself to the cause of China Relief. Under the aegis of the Motion Picture Artists Committee, she hosted fundraising lunches and benefit dinner-dances to raise money for medical supplies for the victims of Japanese aggression. “The American people are democratic and are ready to fight for the principle of democracy, wherever it is threatened,” she wrote in Hollywood Now, the newspaper of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, on 12 March 1938. To attract attention to the cause, she obligingly played to type, modelling and auctioning off high fashion Chinese formal wear (she was a stylish and dedicated clothes horse in fashions both Eastern and Western) and posing with her Hollywood friends offering instruction in chopsticks.

By the late 1930s, Wong’s career was on a downward arc and not even the Sinophilic sentiments of America after Pearl Harbor reversed it. In 1942, she was relegated to Poverty Row, signing with Producers Releasing Corporation for a pair of B programmers, Bombs over Burma (1942) and Lady from Chunking (1943), whose main purpose was to instruct home-front Caucasians on the difference, despite appearances, between the Japanese enemy and the Chinese ally.

After Lady from Chunking, Wong put her screen career on hiatus for the duration. In addition to her work for China Relief, she travelled to Alaska to entertain GIs and, closer to home, escorted Chinese American soldiers to the Hollywood Canteen. In 1943, she may have considered a return to the screen when rumours circulated that Hollywood was contemplating a film about Madame Chiang Kai Shek—but then the same rumours had Joan Crawford pencilled in for the part.

After the war, Wong was out of the public eye for years. Her biographers portray her as a less prosperous Norma Desmond, playing landlady in her four-unit apartment building, drinking too much, and watching too much TV. She was always popular with her colleagues so her prolonged absence was noted and lamented. When she finally returned to the screen in the postwar noir Impact (1949), the Hollywood Reporter sent out a warm greeting—“It’s good to see Anna May Wong back on the screen”—but to see her in a bit part as a maid speaking pidgin English is painful.

Like many Hollywood stars past their sell-by date, Wong turned to television. In 1951, she starred in a short-lived mystery show, The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong on the Du Mont network, in which she plays the chic proprietor of an art gallery who gets caught up in international intrigue. It lasted just three months. “The worst television show by which this reviewer has ever been stunned,” said the appalled critic for the Billboard on 8 September 1951.

In 1955, director William Wyler threw her a lifeline with a small part in a television production of The Letter. Gratifyingly, it sparked a string of small screen job offers. She had featured appearances in The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, Adventures in Paradise, and The Barbara Stanwyck Show, and, on the big screen, we can catch a brief glimpse of her in the Ross Hunter melodrama Portrait in Black (1960). “When I die, my epitaph should be: I died a thousand times,” she told Hollywood columnist Bob Thomas of the Press and Sun Bulletin, who welcomed her comeback in December 1959. “They didn’t know what to do with me at the end, so they killed me off.”

Alas, Wong never got to experience a proper second act revival in her own time. On 2 February 1961, at just 54 years of age, she died “suddenly and unexpectedly” of a heart attack, in the Santa Monica home she shared with her brother Richard, a photographer. Variety’s brief obituary of 8 February ended with a poignant curtain line: “At one time, she commanded big money.” In tribute, the Silent Movie House in Los Angeles programmed Piccadilly, the one film where it all came together for her.

At the time of her death, Wong had been signed to appear in the musical adaptation of Rogers and Hammerstein’s The Flower Drum Song (1961) where, at last, no one in the cast appeared in yellow face.