Art and Culture

A Filmmaker in Spite of Himself

Sacha Guitry disdained cinema as an art form, but with a slew of recent Blu-ray releases, his acidic comedies are finally receiving the attention they deserve.

I.

The playwright and filmmaker Sacha Guitry (1885–1957) remains little known outside France. He was famous for half a century as a writer, actor, and director. During the First World War, his comedies began to dominate theatres, not only in Paris, but throughout the French-speaking world. From the 1930s onwards, he gained renown for his crowd-pleasing movies, while also alienating critics with his high-handed disdain for established conventions of filmmaking. He never thought twice about breaking the rules of “classical French cinema” because he never bothered to learn them in the first place.

Guitry was a star of the “boulevard theatre,” and Parisian audiences loved him for his cynical wit and dazzlingly magniloquent monologues. Most of his plays are farcical sex comedies. Yet when he performed on stage, he demonstrated the commanding manner and exquisite diction of a classical actor. He was fifty before he thought seriously about cinema as a vehicle for his talents. Once he saw how much fun he could have as a director, he became hooked on the process, and ended up making three dozen films.

François Truffaut, an influential film critic who became one of the best-known auteurs of French cinema in the 1960s, praised Guitry’s cavalier, slapdash attitude towards directing films. In Les Films de Ma Vie (1975; translated into English as The Films in My Life, 1978), Truffaut identifies Guitry’s mischievousness as the secret to his appeal: audiences are charmed by him and his work because he is like a spoilt boy who gets away with misbehaving because he makes us laugh.

Of course, Guitry’s flippancy did not always go unpunished in real life. On 8 October 1941, the German writer Ernst Jünger, then an intelligence officer in Paris, wrote in his wartime journal about his first meeting with Guitry at the home of Fernand de Brinon, who was then the Vichy government’s representative to the German High Command:

... I made the acquaintance of Sacha Guitry, whom I found very pleasant. His dramatic side also far outweighs his artistic side. He possesses a tropical personality of the sort I imagine [Alexandre Dumas] had. On his little finger there gleamed a monstrous signet ring with a large embossed monogram SG on the gold surface.

I conversed with him about [Octave] Mirbeau [leading member of the “Décadent” literary movement]. And he told me that the man had died in his arms as he whispered into his ear: ‘Ne collaborer jamais!’ [‘Never collaborate!’]. I am recording this for my collection of last words. What he meant was collaborating on comedies, for in those days the word did not have the odour that it does now.

On 24 August 1942, Guitry’s name was listed in the American weekly Life Magazine as one of “the Frenchmen condemned by the underground for collaborating with Germans: some to be assassinated, others to be tried when France is free.” Guitry’s reputation never fully recovered. Needless to say, in occupied France he was regarded with suspicion by all sides. He was too much of a live wire to be politically trustworthy.

Jünger found Guitry fascinating, and enjoyed spending time with him, but he was less impressed with Guitry’s work as a dramatist. His journal entry for 25 January 1942 notes:

In the Madeleine Theatre in the afternoon to see a play by Sacha Guitry. Enthusiastic applause: “C’est tout à fait Sacha!” [“It’s pure Sacha!”] Cosmopolitan taste is always a matter of perspective, and delights in scene changes, mistaken identity and unexpected characters, as in a hall of mirrors. The complications are so intricate that they are already forgotten on the staircase. Who did what to whom seems irrelevant. The nuances are pursued to such an extreme that nothing is spared.

Jünger’s polite disdain is partly the result of his fastidious literary tastes, but also has something to do with Guitry’s habit of defiantly mocking the Germans, both on stage and in his films. To modern eyes, his satire seems toothless, but during the occupation even gentle teasing could be risky. Guitry got away with it by cultivating relationships with influential Germans, and poking fun at them under the cover of plausible deniability. Was this courageous, or merely self-indulgent? Such questions recur again and again about Guitry’s life and work.

Outside France, only nine of Guitry’s films are available on DVD or Blu-ray. In 2010, the Criterion Collection released Presenting Sacha Guitry in their Eclipse series—a four-disc box-set of DVDs consisting of films he made between 1936 and 1938; in 2018, Arrow Films released a limited-edition box-set of four further films from the same period in both DVD and Blu-ray formats. There is also a 2013 edition in the Eureka Films Masters of Cinema series of Guitry’s 1951 black comedy La Poison; this was released in the US by the Criterion Collection in 2017 with some additional material.

In what follows, I will focus on these films, along with Guitry’s postwar comeback films, Le Comédien and Le Diable boiteux (both 1948), released on DVD and Blu-ray in December 2023 by Éditions Rimini, a small but excellent label in Rennes in northwestern France. Alas these films have no English subtitles; even so, the dialogue should not be a struggle for anyone who has school-level French. Together they are essential to understanding Guitry as he saw himself; Le Diable boiteux is perhaps the central achievement in his oeuvre, which includes over 120 plays—he was never quite the lazy dilettante that he embodied in performance.

II.

Alexandre “Sacha” Guitry was born in St Petersburg on 21 February 1885. His father Lucien Guitry (1860–1925) was the most celebrated French actor of his era and spent most of the 1880s earning a fortune by performing 17th-century classical plays for the francophone Russian nobility. Lucien had been talent-spotted by the legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt, and she became a kind of replacement mother-figure to his two sons. Their real mother, Renée Delmas, divorced Lucien when Sacha was five years old and ignored her children thereafter.

The 1936 film of Guitry’s 1919 play Mon père avait raison (“My Father Was Right”) offers revealing glimpses of how Guitry regarded his parents. The story centres on Charles Bellanger, a serious-minded Parisian gentleman who adores his roguish father Adolphe, a widowed playboy, but is cold and impatient with his ten-year-old son Maurice, whom he decides to send off to boarding school to get rid of him. Maurice is a stand-in for Sacha; Adolphe is Lucien; Charles begins as Lucien and ends as Sacha. Charles’s wife Germaine obviously represents Sacha’s mother, who died when he was a teenager. The depiction is distinctly unflattering.

Early in the film, there is a sudden crisis: Germaine rings to announce that she is about to board a train to flee abroad with her lover, whose existence Charles has never even suspected. Shocked and humiliated by this abandonment, he has a complete change of heart, and decides to take Maurice out of school entirely to educate him wholly by himself. Most of the action takes place twenty years after this crisis, when Maurice is thirty and still living with his father. Germaine, whom nobody has heard from since her elopement, unexpectedly decides to come back home, now that her love affair has finally ended. Meanwhile, Maurice wants to get married, but is reluctant to leave home because he thinks his father can’t live without him.

Mon Père avait raison is one of Guitry’s weaker films, but there are memorable scenes, especially early on, when Adolphe drops in on Charles to offer some spectacularly selfish advice on how to live life pleasurably and without illusions. This is the old man’s only appearance; the rest of the action unfolds after his death, as a demonstration that his philosophy is correct.

When the play was originally staged, Adolphe’s role was performed by Lucien Guitry; Sacha of course played Charles; Parisian audiences thus watched the son transform into the father before their eyes. The film version was made a decade after Lucien’s death. The actor who plays Adolphe, Gaston Dubosc, inevitably lacks the chemistry that Lucien must have had with his son, and in the absence of a counterbalancing force, Sacha dominates the film.

Mon père avait raison turns surprisingly ugly when Guitry the writer decides to enact simultaneous revenge fantasies against his long-dead mother, his first wife (who was eight years his senior, and past forty when he abandoned her), and various mistresses who cuckolded him. For all the self-conscious elegance of the dialogue, there is an emotional rawness to a lot of the action. Much of Guitry’s reputation for misogyny stems from his lifelong resentment of his mother. The slightest reminder of her could make him lose his cool, and much of his long-suppressed rage was vented in the form of wittily cruel epigrams.

Lucien Guitry, for his part, was hardly a responsible father; his idea of parenting involved throwing money at Sacha and his brother Jean so that they would leave him alone to pursue his complicated love life. After Sacha dropped out of school at the age of seventeen, Lucien raised the lad’s allowance so that he would be able to afford a proper mistress. This parenting strategy backfired when Sacha seduced one of his father’s mistresses, Charlotte Lysès, and subsequently married her. Father and son stopped speaking for years.

Lysès made Sacha into a playwright by locking him in a room and forcing him to write. His first successful play, Nono, was staged at the end of 1905. Guitry was wary of appearing on stage himself after his father told him, “You belong in cafés, not theatres.” But in 1906, the lead actor in one of Sacha’s plays fell ill, and Sacha reluctantly had to replace him. To his shock, he found that audiences loved him. Within a few years he managed to become a bigger star than his father.

III.

In 1915, Lysès convinced her husband to think about making a film, even though he despised the medium. He ended up shooting a documentary, Ceux de chez nous (“Those of Our Land”), which features the only film footage in existence of the artists Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and Auguste Rodin, as well as other actors, writers, and celebrities who had been Lucien Guitry’s friends since the 1880s. They all knew Sacha well, and had been trying to reconcile father and son for years.

Ceux de chez nous has the feel of a home movie; when Guitry first presented it in public on 22 November 1915, he narrated it in person. The original 20-minute silent film is available on the Rimini Editions disc of Le Comédien. Some of the footage shows France’s greatest artists in action: Monet smokes and chats as he paints in his garden at Giverny; Rodin sculpts energetically, heedless of all the stone chips flying into his beard; Pierre-Auguste Renoir can barely hold a cigarette, let alone a paintbrush, due to painful arthritis, and his cheerful perseverance with his art seems positively heroic.

But perhaps the most interesting figure on screen is Guitry himself. At the age of thirty, he still seems anxiously deferential in front of his elders. With Sarah Bernhardt, he is seen sitting on a bench in the sunshine; she laughs and reads out a letter as Guitry looks on, as unsure of himself as an adolescent wrestling with puberty. His uneasiness in front of the camera contrasts strikingly with his magisterial air as he narrates the sound version of Ceux de chez nous that was re-edited for television in 1952.

The later reissue is more than twice the length of the original; most of the additional footage features Guitry seated at his desk reading out a prepared text, surrounded by paintings from his impressive private collection. Above his head is a portrait of Lucien, who is seen in a few seconds of footage at the end of the documentary. The film is made to look like a son’s grateful tribute to his father, but Lucien did not appear in the original 1915 cut because father and son were not yet on speaking terms when Ceux de chez nous was shot. The reconciliation only occurred in 1917, after Charlotte Lysès caught him cheating on her and demanded a divorce.

One of Guitry’s last plays with Lysès, Faisons un rêve (“Let’s Make a Dream,” 1916) is perhaps the archetypical Sacha Guitry sex comedy. The story is simple: a notorious ladies’ man decides to seduce the wife of a boring businessman, and runs into unexpected complications. As in much of Guitry’s work, the dialogue often feels like a distorted confession: Guitry wrote this play in the middle of a passionate affair with Yvonne Printemps, who became his second wife and best-known leading lady.

The most famous scene in Faisons un rêve is a tour-de-force monologue in which Guitry’s character waits at home with mounting impatience because his intended conquest has not arrived yet. On the page, this scene seems wordy and unfunny. Indeed, most of Guitry’s plays don’t read very well: like David Mamet’s, they are not meant to be works of literature; they are more like the verbal equivalent of musical scores. This particular monologue is a challenge even for classically trained actors because of its peculiar rhythms and sheer length; but when performed properly it never fails to bring down the house.

Guitry knew that he had no talent for the sort of naturalistic acting that his father had pioneered, so he went to the other extreme. His scripts veer between casual, sometimes startlingly realistic banter, and elaborate speeches that are so self-consciously artificial that you almost expect Guitry to stop and take a bow in the middle of his performance. This quality is on full display in the 1936 film version of Faisons un rêve, which alas was made after his relationship with Yvonne Printemps was over.

Printemps was a brilliant comedienne, as can be glimpsed in an Italian newsreel from 1932 that contains the only surviving footage of her onstage with Guitry. She remained his leading lady until she left him in 1932 for Pierre Fresnay, who is best known today for playing Le Captaine de Boeldieu in Jean Renoir’s classic war film La Grande Illusion (1937). Printemps brought out the best in Guitry as a writer. Perhaps his finest stage play is Désiré (1927), and the 1937 film version is one of his masterpieces. It was so imaginatively adapted for the screen that you can forget that it was originally written for the theatre.

Guitry stars as Désiré, a fourth-generation servant who is devoted to his work, but who has a bad habit of falling in love with his lady employers, who also become besotted with him but can never really be his. Désiré is almost a tragedy, except that it boasts some of the funniest sequences that Guitry ever devised, including a beautifully choreographed scene in which Désiré helps his employers entertain a politician’s deaf wife at the dinner table while her husband carries on gambling, having forgotten that he is keeping his host waiting. Guitry orchestrates his actors masterfully: even the weakest member of the ensemble comes off looking like a comedy genius. That weak link turns out to be the leading lady, Jacqueline Delubac.

The camera loved Delubac; but as a performer she could not hold a candle to Yvonne Printemps. Even so, she dreamt of being a movie star. Guitry was twice her age when they married. His fourth wife, Geneviève de Séréville, would be even younger, and when Guitry proposed marriage to his fifth wife, Lana Marconi, he told her frankly that she would be his widow. Delubac, Séréville, and Marconi were not really actresses, but Guitry did his best to mould them into stars anyway. At least Delubac had obvious potential, unlike the others.

IV.

By the time Delubac talked her husband into making films for her, he was already fifty. She breathed new life into Guitry’s career, and helped him discover that his real vocation was the cinema (a fact that he denied to the end of his life, even when he had all but abandoned the theatre even as a spectator). Admittedly, Guitry’s first full-length film Pasteur (1935) is just a photographed stage play, but he was openly using this project as an opportunity to teach himself moviemaking.

Guitry’s first original venture for the cinema, Bonne Chance (“Good Luck,” 1935), is a charming road movie about an artist (Guitry) who is secretly in love with a laundress (Delubac), and always wishes her “Good luck!” when she passes by his window. Then one day she wins the lottery and feels obliged to split her winnings with him. There are some lovely scenes, but the film reveals Guitry’s fundamental weakness as a dramatist: his stories are often lazily conceived.

The sparkle of Guitry’s dialogue can never fully mask the thinness of his dramatic conflicts and plotting. Even his most inspired work sometimes feels like it needs at least another draft or two. This is particularly true of Roman d’un tricheur (“The Story of a Cheat,” 1936), which is an amazingly playful piece of filmmaking. Orson Welles was particularly impressed by what he saw, and adopted several of Guitry’s innovations in Citizen Kane (1941). Roman d’un tricheur remains Guitry’s best-loved film among connoisseurs of cinema, if not general audiences—the main character is not very sympathetic, while the narrative feels like a barely disguised excuse to experiment with various storytelling techniques.

Roman d’un tricheur is based on Guitry’s only novel, Mémoires d’un tricheur (“Memoirs of a Cheat,” 1935), the fictional confession of a man who learned early in life that honesty does not pay. Most of the story is told in flashback, as a silent film narrated by Guitry, and the voiceover amounts to a magnificent performance in its own right. The inventive opening credits are presented in the form of a witty documentary about the making of the film, as Guitry introduces the audience to the cast and crew one by one, beginning with the composer Adolphe Borchard. Nobody is neglected or ignored, and you can see why everyone who worked with Guitry adored him.

Guitry’s generosity was partly tactical: he made his collaborators work very hard. Between April 1935 and December 1938, he completed ten feature films, as well as a half-hour film in verse that he finished shooting in under seven hours. During the same period, he also staged ten new plays. You wonder how he found the time to write so much, let alone carry out research for his elaborate costume dramas.

Guitry’s mansion in the avenue Élisée-Reclus in Paris was like a museum of French culture, with Impressionist paintings cluttering the walls, a sculpture by Rodin in the garden, and an impressive collection of rare books, manuscripts, and historical artefacts. He was one of the best-known art collectors of his time; he thought he could become a great man by surrounding himself with great men’s creations, as if he could absorb greatness by osmosis. Of course, the great man who obsessed him most was Lucien Guitry, from whom he inherited this house in 1925.

Early in his career, Guitry began writing stage plays about major writers, artists, and figures from history as an excuse to read about all the things that he had ignored in school. His autodidactic mania culminated in a series of patriotic historical movies that remain among his best-loved achievements. Purely as history, these films are all preposterous. Yet they are held together by Guitry’s sense of spectacle, and infectious love for his country.

His first effort in this vein, Les Perles de la couronne (“The Pearls of the Crown,” 1938), is an ambitiously staged tall tale that gives Guitry a chance to dress up like King François I of France and Emperor Napoléon III. It drags a little because the story is undercooked. Much better is Remontons les Champs-Élysées (“Let’s Go Back Up the Champs-Élysées,” 1938), in which Guitry plays a schoolmaster who decides to entertain his students with the story of the most famous road in Paris.

This is no ordinary teacher: he turns out to be descended from various bastards of Napoleon, King Louis XV, and the revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. Despite his Revolutionary lineage, he seems to envision France as a giant amusement park, at one point explaining to his class that the film’s title is what young lovers tell taxi drivers to give them an opportunity to make out in the back seat for a little longer.

The best section in the film comes in the first half, where Guitry plays King Louis XV in an uproarious sex farce. He and the cast have the time of their lives re-enacting court intrigues whilst wearing extravagantly expensive costumes. Jacqueline Delubac makes her last appearance in a Guitry film as a seductive fortune-teller at a carnival who tells the king when he is going to die.

Remontons les Champs-Élysées is the first film in which Guitry uses the death of a great man as a dress rehearsal for his own passing. Here Louis XV dies alone in bed whilst his courtiers insolently gossip in an antechamber, revealing that they never really cared for him as a man, and have already forgotten him and moved on to the next monarch. Guitry had a morbid fascination with this sort of melancholy death scene, and he would stage similar ones in Le Comédien and Le Diable boiteux.

V.

After Remontons les Champs-Élysées, Jacqueline Delubac asked for a divorce. It was easy to see this coming for anybody who managed to sit through Quadrille, which was first staged as a play in September 1937 (the cinema version was released in January 1938). This is an effervescent sex farce with a sour, gloomy undertone. Guitry stars as a powerful Parisian editor who is cuckolded by an American movie star, and there is a rare note of self-loathing in the script.

Guitry’s fourth wife came from an aristocratic family, and his in-laws looked down on him as “a mere entertainer.” Over time, his wife came to share her parents’ views. Ernst Jünger lunched with the couple on 15 October 1941, and hints that they were obviously unsuited to one another:

I was astonished again by his effusive personality, especially when he told anecdotes of his encounters with royalty. When talking about different people, he would accompany his words with expressive gestures. During the conversation, he used his large horn-rimmed glasses to great dramatic effect. It dawns on me that in the case of such talent, the whole reservoir of personality that a marriage can possess gets used up by the man.

Of course, the marriage was disastrous. Guitry’s sense that he had made a terrible mistake is reflected in his scripts from the period. The dialogue, in particular, seems increasingly bitter and misanthropic, as in the 1942 play N’écoutez pas, mesdames! (“Don’t Listen, Ladies!”). Guitry’s opening monologue here is reminiscent of the brilliant solo scene from Faisons un rêve, except that this time the hero is not a triumphant lover, but a jealous, frustrated cuckold. Yet, for all its darkness and misogyny, this is one of Guitry’s most beloved plays; as always, painful domestic turmoil inspired some of his sharpest one-liners.

In 1939, shortly after the outbreak of war, Guitry released one of his most daring films, Ils étaient neuf célibataires (“Nine Bachelors”), in which he plays an unscrupulous businessman who hatches a plan to sell down-and-out Frenchmen as husbands to rich foreign women who are in danger of being kicked out of the country. There is something in this comedy to offend everybody. Sadly, this was to be Guitry’s only foray into explicit political satire: after the fall of France, he was forced to contend with a great deal of arbitrary censorship.

Guitry felt it was his duty to keep up his fellow Frenchmen’s spirits in the wake of their defeat, and reassure them that their nation was still great. His 1943 film Donne-moi tes yeux (“The Last Mistress”) includes an extraordinary prologue featuring a series of paintings and sculptures by France’s most distinguished artists: these were all produced, Guitry says, in 1871, in the wake of France’s humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Audiences must have wondered how Guitry got away with such explicitly anti-German content; he constantly emphasised the grandeur of French culture as a means of implying his nation’s superiority to its barbarous occupiers. Alas, he did not always exercise tact when doing so.

In 1942, Guitry published a deluxe coffee-table book, De Jeanne d’Arc à Philippe Pétain (“From Joan of Arc to Philippe Pétain”) that would cause him headaches for years afterwards. Marshal Pétain himself told him that it would be unwise to publish a book with such a title. Most educated people would feel self-conscious about owning such a book even today, because of its potential political implications. This is a pity, because the contents are interesting for their own sake, and have nothing to do with the Vichy government.

De Jeanne d’Arc à Philippe Pétain is a patriotic celebration of French culture that shows off many of the highlights from Guitry’s vast personal collections. Guitry assembled texts and pictures that were either created by or associated with every major French writer, artist, composer, philosopher, scientist and statesman he could think of. The volume ends with an assurance that France would eventually rise again, with the aid of the nation’s indomitable spirit, which was manifest in France’s cultural achievements. It is easy to see how all this might have annoyed people who were risking their lives every day in underground resistance movements.

During the occupation, Guitry ran significant risks to protect Jewish friends including the writer Tristan Bernard, and Maurice Goudeket, whose wife was the novelist Colette. Yet he also spent a great deal of time making snide remarks whilst drinking champagne with people like Otto Abetz, the Nazi ambassador to Vichy France. Members of the Résistance were not impressed by this kind of thing. On the morning of 23 August 1944, Guitry was taken into custody, and spent two months at the notorious Drancy internment camp.

The courts took three years to acquit him of collaboration, and his name was officially cleared on 8 August 1947. Meanwhile, his health began to decline rapidly. Yet during the final decade of his life, Guitry produced some of his very finest work. His postwar comeback film was to have been Le Diable boiteux, but the censors rejected the script, so he hastily transformed it into a stage play. He still intended to film it, but first he would have to reassert his place in French culture, and remind the public whose son he was. Then he would be in a better bargaining position with the authorities, if they turned him down a second time.

Le Comédien is based on a play that Guitry wrote for Lucien in 1921. It was explicitly intended as a portrait of his father, warts and all, and it seems inappropriate to call it a tribute. When Lucien was alive, the main character was simply called The Actor; in the film version he is explicitly called Lucien Guitry. Sacha plays the role himself.

The play begins with a confrontation in a dressing-room between The Actor and his jealous lover, who leaves him because she thinks he’s having an affair with a younger actress. Then The Actor receives a visit from a friend he hasn’t seen in thirty years; the friend tells him that his young niece is in love with The Actor, who relieves his friend’s embarrassment by promptly seducing the niece and making her his mistress. She is not yet twenty; he is past fifty. But the real conflict has nothing to do with age: she wants to become an actress, but she has no talent, only beauty, youth, and the fervour of a superfan. The stage is simply not her vocation. The Actor ends up alone, loved only by his audiences.

Evidently Lucien Guitry led a lonely, sordid life. His son’s ambivalence about his legacy is palpable in the screen adaptation of Le Comédien, in which Guitry plays not only his father, but also his own younger self, directing Lucien onstage in Pasteur in 1919. Sacha manages to pull off the double role without awkwardness, and the illusion is completely convincing. By the end of the film, the audience is left wondering: which one is really The Actor: Lucien or Sacha? The psychological complexities of the film’s closing scenes are dizzying.

After the success of Le Comédien, Guitry finally managed to get his screenplay of Le Diable boiteux past the censors. The stage version had been a hit in Paris; but the film is immeasurably better, and marks a defiant return to form. Indeed, Le Diable boiteux is perhaps Guitry’s greatest achievement as an actor, writer, or director: he plays the role that he was born to play, as Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, who was either the most nimble-footed diplomat in European history, or else a cynical, devious, self-centred traitor who betrayed every regime he served.

Talleyrand was legendarily amoral: he faithfully served the Church, the ancien régime, the Revolution, Napoleon’s Empire, the restored Bourbon dynasty, and the Orléaniste constitutional monarchy, ultimately claiming loyalty to whoever was in power rather than to any individual. Everybody feared his cunning; Guitry depicts Talleyrand not as a sociopath, but as a radical patriot who was loyal to France and France alone.

The funniest scenes in Le Diable boiteux show Talleyrand outwitting an exasperated Napoleon, played by Émile Drain, who doubles as one of Talleyrand’s lackeys. Indeed, all four of the actors who play the monarchs whom Talleyrand served also have secondary roles as his domestic servants. Audiences are meant to notice this, especially when Talleyrand is being carried up staircases by his staff. The film is exquisitely provocative throughout; certainly, the very idea of portraying Talleyrand as a hero of French history is outrageous. Yet this film is by no means Guitry’s most subversive comedy.

VI.

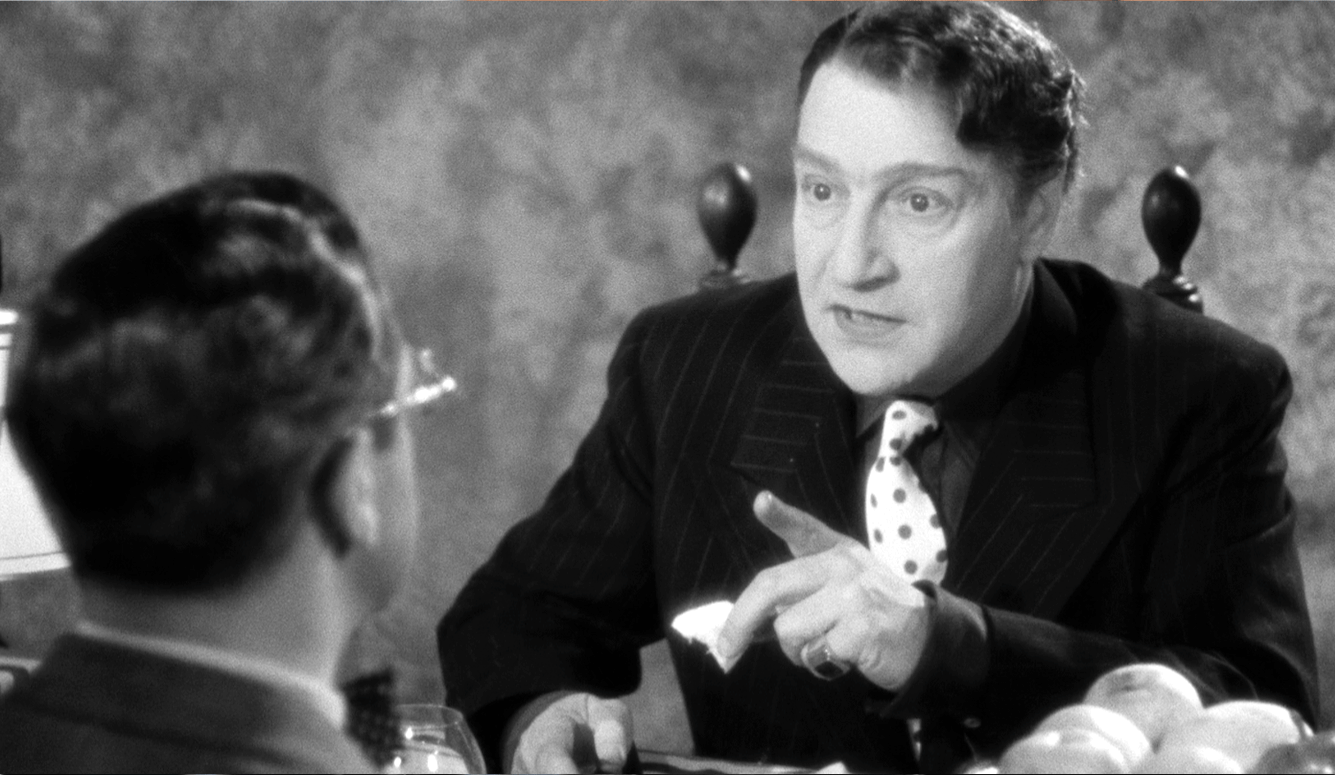

Guitry was recovering from stomach surgery when he got the idea for La Poison (1951), a film about a husband and wife who have fallen out of love, and begin plotting to murder one another. He decided to write this script as a vehicle for Michel Simon, the clumsy-looking comedian whose most iconic role is as the unpredictable title character in Jean Renoir’s 1932 film Boudu sauvé des eaux (“Boudu Saved From Drowning”). Simon and Guitry brought out the best in one another, and their collaboration turned out to be a high point in both men’s careers.

In La Poison, Simon plays Paul Braconnier, a gardener who lives in an idyllic village in Normandy. His neighbours all know how much he and his wife Blandine hate each other, and early in the film, Braconnier confesses as much to a kindly local priest (played by Albert Duvaleix). Blandine, for her part, is a sullen, spiteful alcoholic; disappointment has made her bitter, and Germaine Reuver gives a frightening performance, emphasising Blandine’s deep sadness as well as her self-fuelling rage.

One night, when Blandine has drunk herself to blackout on cheap red wine, Braconnier hears a radio interview with a self-satisfied barrister, Maître Aubanel (Jean Debucourt), who has defended a hundred murderers in court and succeeded in winning acquittals for all of them. Braconnier decides to get the lawyer to help him plot his wife’s murder, little realising that Blandine has already bought poison to pour into his wine.

Guitry completed shooting La Poison ahead of schedule, in well under a fortnight, and decided on the spur of the moment to shoot one of his celebrated credit sequences. When the film opens, Guitry is seen writing out a generous dedication to Michel Simon, who is visibly moved by the tribute before thanking each member of the cast and crew for their work. At last, he starts pouring out champagne for everybody as the camera fades to black for the action to begin. The atmosphere of mutual respect and love undercuts the potential bleakness of the subsequent narrative. Indeed, La Poison is a disturbingly sunny film.

Some scenes are also unexpectedly poignant. During the credits, Lucienne Delyle performs a charming love song, “Et la vie est en fête” (“And Life Continues to Celebrate”), that is repeated a few times during the film. Under most circumstances, this would be a pleasantly forgettable tune; but in context it is heartbreaking: Delyle’s cheerful celebration of young love provides the soundtrack to one of the Braconniers’ silent, miserable meals. They eat supper every night with the radio on to avoid having to speak to one another. You come to feel their pain, and understand why they might want to kill each other.

After La Poison, Guitry found the strength to make another seven films, including three lavish historical pageants, and two more black comedies with Michel Simon, one of which he quite literally directed from his deathbed. On the morning of 24 July 1957, Guitry died. Twelve thousand mourners paid their respects to his body at his mansion on the Avenue Élisée-Reclus, and on 27 July he was buried at the Cimitière de Montparnasse, next to his father and brother.

Guitry’s museum-like house was demolished in the 1960s. His art collection has long since been sold off, yet his presence remains palpable in French theatres. His plays are regularly revived in Paris even now. For all that, his most enduring achievements are surely in the cinema, as was obvious at the Sacha Guitry retrospective in July 2023 at the La Rochelle International Film Festival. Even the texts of Faisons un rêve, Le Comédien, and Désiré pale in comparison to Guitry’s own dazzling screen adaptations of these works.

Like his similarly multi-talented compatriots Jean Cocteau and Marcel Pagnol, Guitry was not so much a Renaissance man as a born filmmaker with a lot of distracting hobbies (writing and starring in plays, for example). He regarded cinema as a minor art form without any authentic tradition or history, and this attitude enabled him to pursue his idiosyncratic vision without the inferiority complex that often marred his attempts at literary work. The freedom and confidence of his movies can be exhilarating: you feel him having fun with the medium, unburdened by any sense of obligation towards the theatre, or by Lucien Guitry’s legacy.

Early in his career, Guitry told an interviewer that he thought the cinema had peaked as early as 1912. Although he came to appreciate film as a means of expressing himself, he could never fully take it seriously. But if he had never started making movies, he would have been forgotten long ago, like every other writer of French boulevard comedies—including Lucien Guitry, who is now remembered only as the father of a famous filmmaker.