editors choice

Quillette Editors’ Choice of 2024

Jamie, Jon, Iona, and Claire share their favourite essays from this year.

Quillette published approximately 465 articles in 2024, meaning that each editor edits over one hundred articles a year.

It’s therefore a difficult choice to choose three favourites, but that’s what I’ve asked our editors to do. Their answers follow.

What were yours? Do let us know in the comments section.

Jamie Palmer’s picks

To coincide with the release of a new “ultimate cut” of Tinto Brass’s notorious 1979 film Caligula, Jaspreet Singh Boparai has provided an erudite top-to-bottom analysis of one of cinema’s greatest disasters. Boparai examines what we know about the real Roman emperor, the collision of monumental egos behind the attempt to bring his story to the screen, and the creative calamity that resulted. Caligula’s five-year reign was marked by feuds, decadent excess, and insanity, so it’s fitting that the film’s fraught production was also afflicted by all the above. I have to say that, for all its obvious problems, I have always been fond of the film—there is really nothing else like it.

Fifty years after Ronald DeFeo murdered his parents and siblings in the family home at 112 Ocean Avenue, Kevin Mims looks back at the story of the Amityville Horror. A year after the DeFeo murders, the house was purchased by George and Kathy Lutz, who fled their new home just 28 days after they moved in. The Lutzes claimed the house was haunted, and their wild stories of paranormal aggression and demonic possession were subsequently turned into a blockbuster novel (marketed as a true story) by Jay Anson and then a Hollywood film starring James Brolin, Margot Kidder, and Rod Steiger. Mims’s essay offers a perceptive and beautifully structured analysis of how a terrible crime and a literary hoax produced a pop-cultural phenomenon.

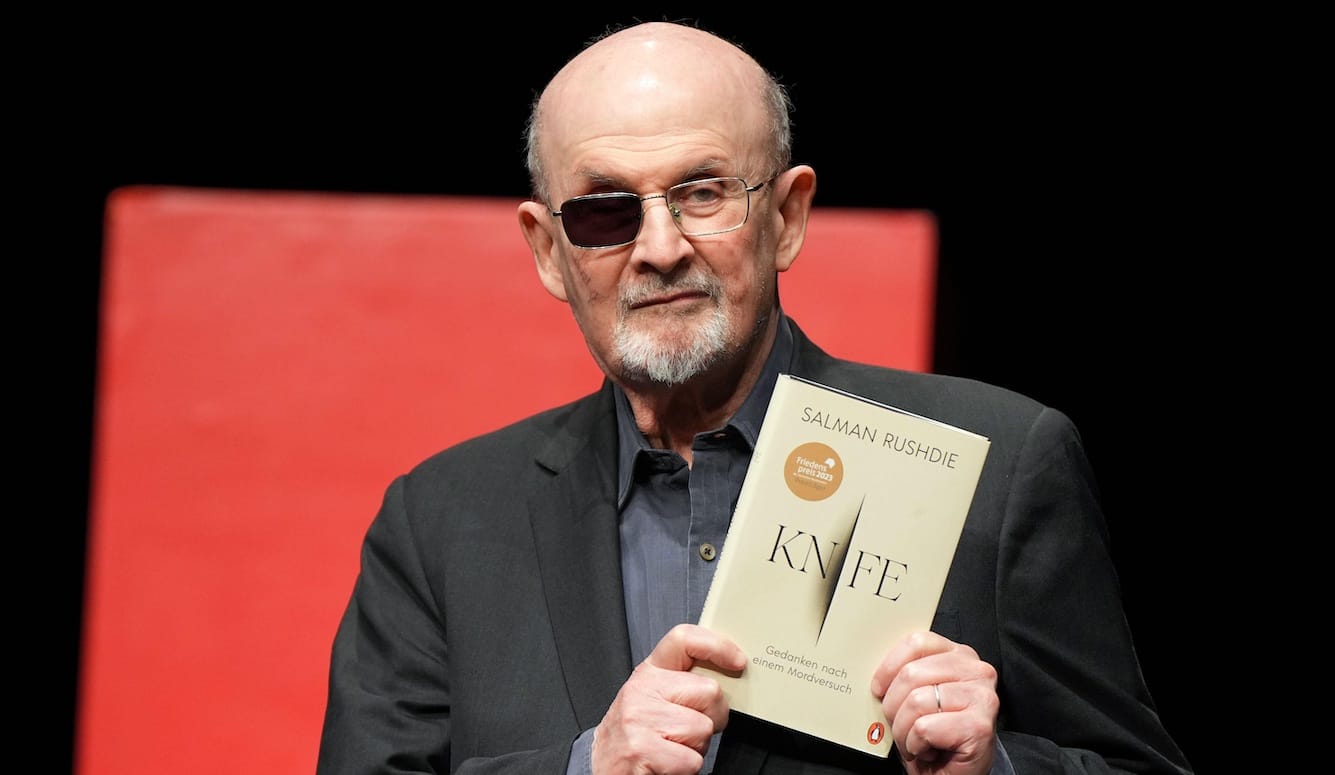

A lovely review by Paul Berman of Salman Rushdie’s short memoir Knife. Written as he convalesced after an attempt on his life by an Islamist fanatic, Rushdie’s book offers poignant reflections on mortality, stoicism, and survival. It is, Berman writes, “a moving book, more affecting, I think, than anything else he has written—a moving book in itself, that is. But Knife is moving also because it carves a scar retroactively and even prospectively across the whole of Rushdie’s literary career, past and future.”

Jonathan Kay’s picks

“Quillette is where free thought lives” is the tag line that precedes our podcasts. That’s true, of course. But it’s also an incomplete description of what makes Quillette special. Another distinguishing quality: Quillette is where big stories get the space they need to be told properly. Indeed, my writers are sometimes shocked when they ask what our word limit is, and I tell them, there isn’t any: Your job is to keep adding information the reader needs to know. And my job is to let you know when that job is complete.

In that spirit, my favourite 2024 Quillette articles were all authoritative essays, rich in detail, each one tackling a controversial subject at significant length.

The first (following no particular order) is Carole Hooven’s 22 March 2024 piece, Why Do Men Dominate Chess? The article was timely, as chess’s international governing body was then wrestling with the question of whether biologically male players who self-identify as women should be permitted to play in women’s categories. But most of the article addressed the more basic question of why protected female chess categories have been seen as necessary in the first place. Many will assume that the reason must lie in some basic difference that distinguishes male and female brains. And there’s some evidence pointing in this direction. But Hooven’s analysis is a lot more nuanced than that. And while she’s no chess grandmaster, her Harvard University research on human spatial ability closely informed her expert analysis.

My second pick is Gaslighting Scottish Rape Victims in the Name of Trans Inclusion, by Joan Smith. If Hooven sometimes treads lightly with her language so as to avoid stepping on culture-war land mines, Smith takes the opposite approach—stomping on them with great gusto, terrific rhetorical effect, and zero apologies. Smith’s subject was the rise and fall of Mridul Wadhwa, a trans-identified CEO of the Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre who was ultimately suspended from the role in the wake of complaints. In her article, Smith steps readers through the process by which Wadhwa was able to achieve a position of such prominence within a woman’s institution, as well as the events that finally precipitated Wadhwa’s ouster.

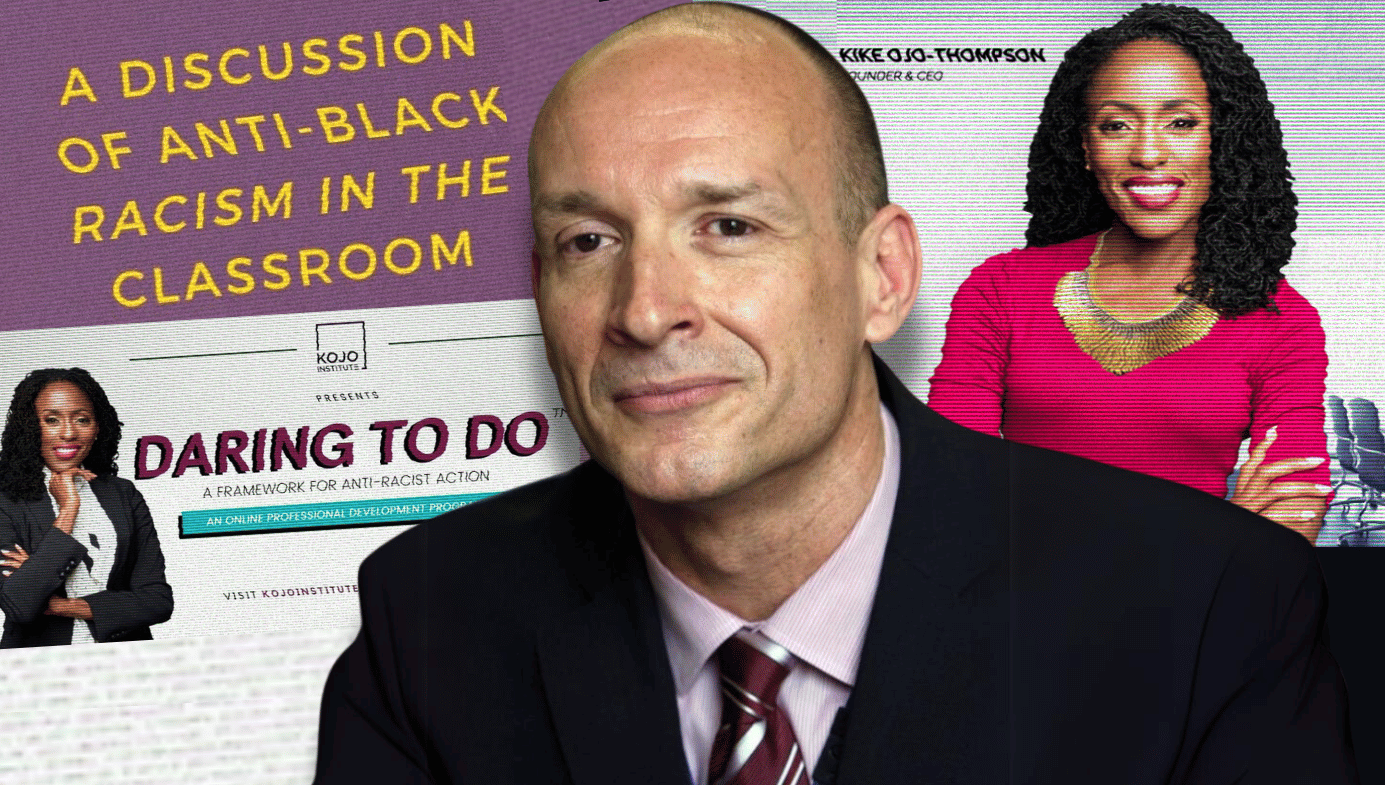

My third pick goes to my fellow Canadian, Ari David Blaff, a young writer who meticulously documented the career of infamous “anti-racist” educator Kike Ojo-Thompson, whose vexatious abuse of Toronto school principal Richard Bilkszto preceded his suicide. As Blaff documents in his article, this was hardly the only time that Ojo-Thompson used questionable methods in her training. Like many of our best Quillette essays, Blaff’s was based on leaked materials that were inaccessible to other media outlets: He watched many hours of Ojo-Thompson’s anti-racist lectures to a Toronto-area school board, and catalogued the numerous false and incendiary claims she made about Canadian society and history.

Iona Italia’s picks

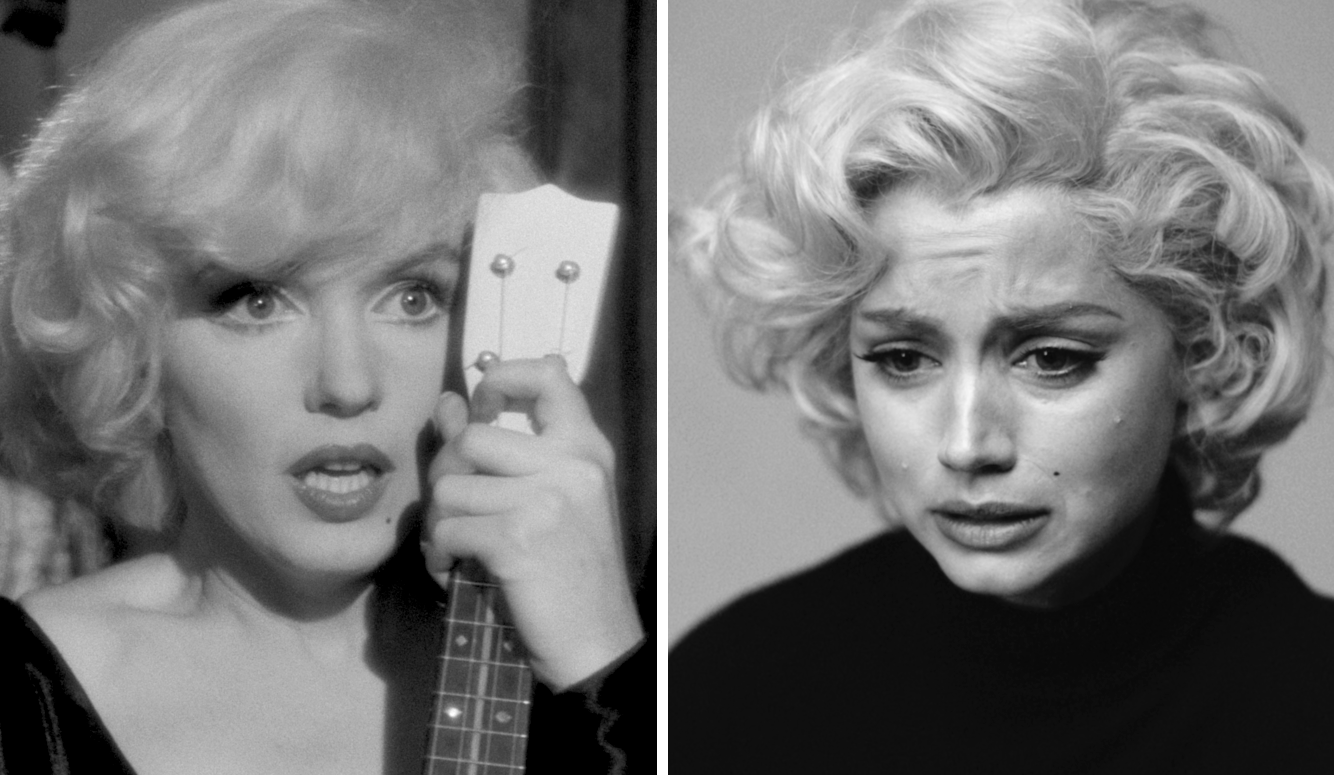

My first pick is Blonde on Blonde. In this magisterial review, Charlotte Allen first delves into the facts of Marilyn Monroe’s real life in intricate detail and contrasts them with the kaleidoscopic images of the actress presented by biographers and other myth-makers and then explains how Andrew Dominik created a gripping morality play out of the actress’s troubled existence. Allen helped me parse Dominik’s artistic vision and as result I rewatched—and loved—the film, which I had not enjoyed on first viewing. The essay also made me re-evaluate many things I thought I knew about Marilyn.

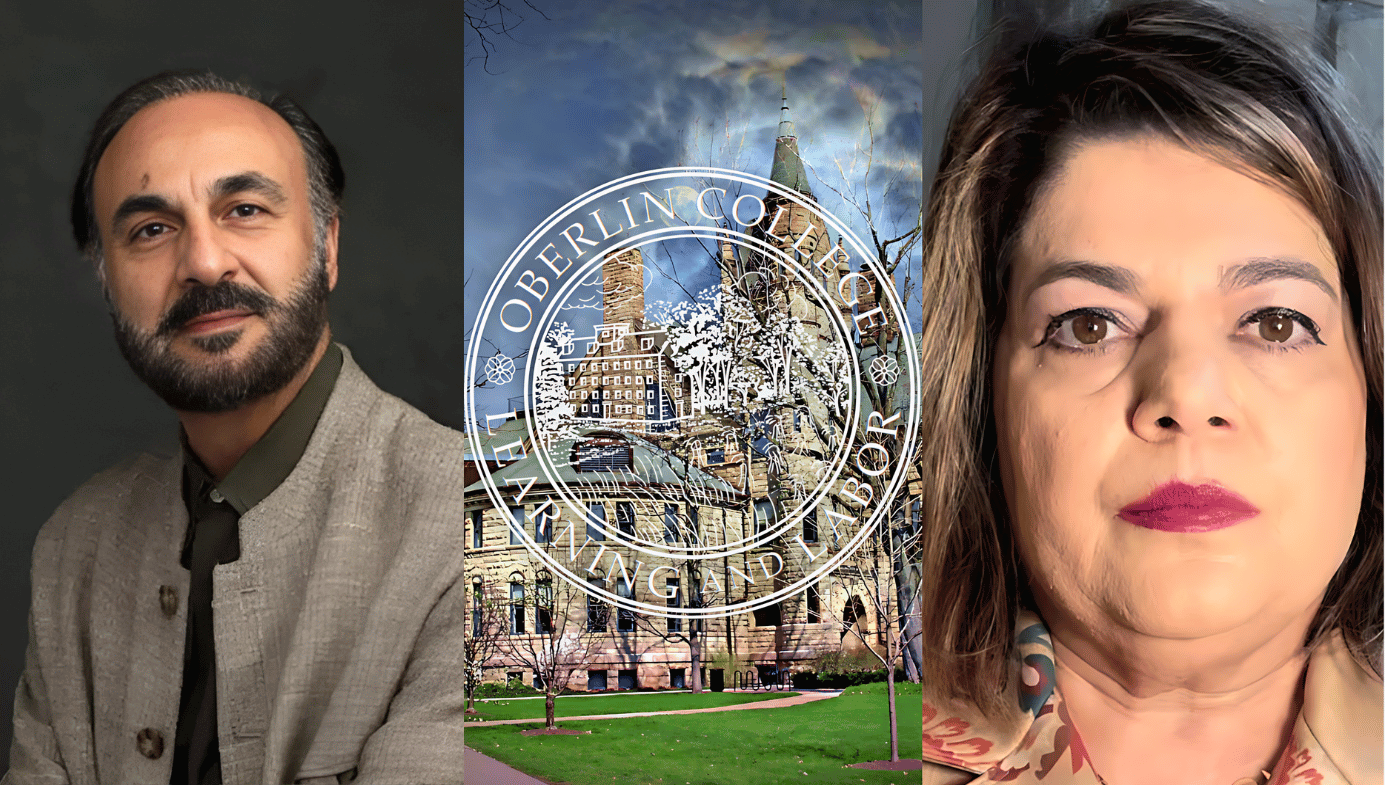

My second pick is The Professor, His Nemesis, and a Scandal at Oberlin. In this meticulously researched report, Roya Hakakian relates how a spokesman for Iran’s brutal totalitarian regime weaselled his way into US academe, despite lacking any serious scholarly credentials. As Hakakian reports, Mohammad Jafar Mahallati never severed his ties with the mullahs nor apologised for the murders of innocents that took place on his watch. He coasted through to a chair, thanks to the exasperating naïveté of American professors and administrators. It’s an extraordinary object lesson in how an unscrupulous actor can take advantage of academia’s lip service to social justice values to game the system and conceal his crimes.

My final pick is Death of a Repentant Iconoclast. Before reading this article, I had never heard of Steve Albini nor did I know much about the music industry he was part of. But Ari Gandsman is a compelling storyteller and this is a fantastic story. At its heart, it’s not just about Albini: it’s about the ways in which so many artists turn from rebels to conformists, about the replacement of authentic howls of rage with the soulless mouthing of platitudes. It’s about how ideological conformity is killing art.

Claire Lehmann’s picks

Mainstream feminist discourse on sexual assault teaches women to embrace a posture of victimhood: all men are potential rapists, interviews at police stations and examinations at hospitals may as well be extensions of an assault, the court system is stacked in offenders’ favour. Larissa Phillips turns this conventional wisdom on its head. A victim of a brutal attack by strangers in Italy, Phillips explains how her decision to report the crime and testify in court helped her recovery—contrary to what she had been taught. Through a meticulous reconstruction of her own assault, Phillips makes a compelling case for fighting back—both physically and psychologically. In making the active choice to move beyond trauma, Phillips’ story shows the strength of the human spirit.

My second pick is Izabella Tabarovsky’s analysis of how Soviet-era propaganda shapes anti-Israel rhetoric. As protestors worldwide brandish signs equating Israel with Nazis, decrying a “Zionist genocide,” Tabarovsky traces this symbolism to its Cold War roots. She shows how the Soviet Union, after 1967, deliberately spread an anti-Zionist propaganda campaign that blended antisemitic tropes with leftist political language, and how today’s progressive rhetoric reproduces, word for word, Soviet-era materials. It’s an extraordinary lesson in how totalitarian messaging can outlive its creators and infiltrate the Western psyche.

My final choice this year continues the Soviet theme with Sean McMeekin’s expansive history of communism, aptly titled To Overthrow the World. He traces communism from its proto-forms in religious sects that preached radical equality, and the intellectuals of Revolutionary France, to its manifestation as state terror under Lenin and Stalin. McMeekin shows why communist ideas attract followers: blending utopian dreams with our basic desire for fairness. The book works as both history and warning by showing how this ideology is a civilisational pathogen which is able to lie dormant for years, waiting for the right time to spread.