Education

The Professor, His Nemesis, and a Scandal at Oberlin

The story of how a liberal college promoted and defended an Iranian Islamist and betrayed its own values.

I. A Disappearance

On 28 November 2023, the profile of a tenured professor at Oberlin College disappeared from the school’s website. Only a day earlier, typing Mohammad Jafar Mahallati’s name into the site’s search box returned a page with an extensive biography and links to several of his posts and videos. His photograph was there, too: a bearded man with a greying hairline and a reticent smile that suited his title of Professor of Peace and Friendship Studies. Since 2007, he had been among the most prominent professors on campus.

A former top diplomat who had represented Iran at the United Nations from 1987–89, Mahallati had brought a certain metropolitan pizzazz to the small college, along with glamorous tales from his days of hobnobbing with a global who’s who of politicians and diplomats. Among academics, where consensus is hard to reach, nearly everyone remembers Mahallati as “magisterial.” If Shi’ism had a campaign ad made for the American consumer, Mahallati—who had swapped the Western suit and tie for the mandarin-collar blazer and shirt and drove a siren-red BMW around town—would be that ad.

Even the locals were smitten. The Iranian professor who had given them an annual Day of Friendship, complete with rainbow flags and peace t-shirts, was all the proof they needed that the George W. Bush administration was wrong to call Iran an evil state. With his arrival at Oberlin in 2007, he managed to infuse the humble small town with an air of cosmopolitan grandeur. And a few years later, he was appointed to the prestigious Nancy Schrom Dye Chair in Middle East and North African Studies. The chair’s namesake, Nancy Shrom Dye, was Oberlin’s president from 1994–2007, and it was Dye who brought Mahallati to Oberlin after she met him during two trips to Iran in the mid-2000s.

Now, all traces of that same man—including the nameplate on his office door and his course titles in the online catalogue—have been expunged from Oberlin, with no explanation offered beyond the words “on indefinite leave.” In any other year, the dismissal of a once-celebrated professor, long championed by the college’s highest officials, might not have been worthy of much attention. But this has hardly been just another year for American academia.

The anti-Israel protests that swept through some of the nation’s most august campuses may have been focused on the war in Gaza, but the rhetoric of the participants—whether or not they were Muslim—was frequently laced with Islamist jargon. Students have lined up to perform ritual Muslim prayers, wave Hezbollah or Hamas flags, and repeat Arabic words most of them do not understand. These sympathies among born-and-bred American youth—most of whom, claiming to be atheists, hailed from Christian households—betray an ideological influence that, long before 7 October 2023, had been quietly encroaching upon America’s colleges and universities.

Against this backdrop, the story of Mahallati, one of the earliest purveyors of this influence, assumes a significance that transcends Oberlin itself. To learn how he got his foothold at the college, and how he remained there despite his inadequate scholarly and professorial credentials, is to see how one Islamist propagandist preyed on American “progressive” sympathies to deceive the very people who had welcomed him into their midst.

II. The Professor and His Nemesis

For thirteen years, Mohammad Jafar Mahallati led a charmed life at Oberlin, which is how he led much of his life despite the occasional setback and disappointment. Mahallati is the son of one of Iran’s most powerful ayatollahs, and in the aftermath of the 1979 Islamic revolution, he claimed his place among the new ruling elite. Although he had no academic experience, Mahallati assumed the chairmanship of the economics department at Kerman University when he was just 26. And although he had never been in politics or held a government position, shortly thereafter, he briefly became the governor of the county of Jiroft. It took several other career test-drives before he entered Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1981. Though he had eyed the post of foreign minister, he settled for the job of chief UN liaison.

In 1987, he finally found the international spotlight when he was named ambassador to the United Nations; but, there too, his tenure ended abruptly less than two years later. The circumstances of his departure remain murky. Thereafter, he refashioned himself as an academic, and wandered from one ivy-league institution to the next as a visiting fellow. He became a graduate student, and later a PhD candidate, until he finally found a home at Oberlin in 2007.

But in 2020, the safety of that home, where no one had ever questioned him about his past or the regime he had served, was suddenly compromised when an Iranian woman named Lawdan Bazargan spotted him at Oberlin. Stout and diminutive at five-foot-three, Bazargan had been hunting for agents of Iran’s regime around the world, and she arrived in town bearing knowledge of the secrets Mahallati had been careful to keep buried. Her pursuit of individuals like Mahallati has been a deeply personal and lifelong political crusade—the kind that only those who have suffered a great loss can wage.

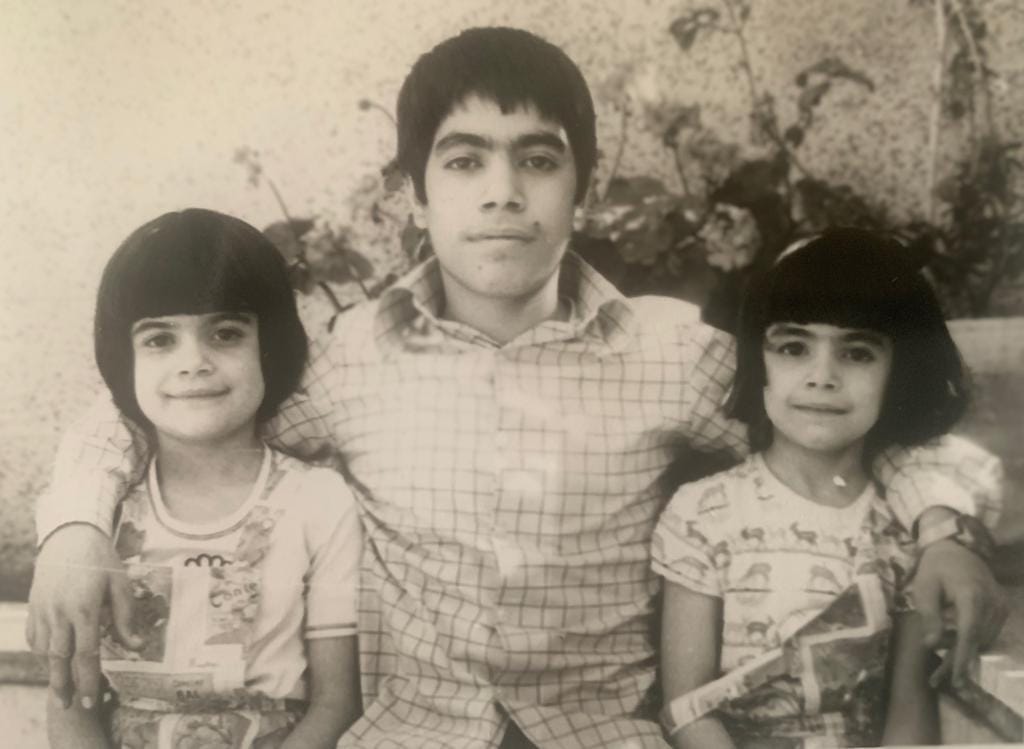

Bazargan belongs to a community of families whose loved ones were murdered in the largest massacre of political prisoners in Iran’s history. The slaughter, which took place in the summer of 1988, was a magnum opus in Ayatollah Khomeini’s violent canon. As the founder of the Islamic Republic and its supreme leader at the time, Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering the hanging of all political prisoners who were either communists or members of the People's Mujahedin Organization of Iran (MEK). If they had not expressed remorse for their past acts or had yet to swear allegiance to the regime, they had to be put to death lest they go free and challenge his reign. Bazargan’s 29-year-old brother, Bijan (pronounced bee·zhan), a Marxist activist who had already served six years of a ten-year sentence, was among the nearly 4,000 people summarily executed that summer.

For days, the authorities kept the news of Bijan’s death from the family. And when the family finally learned of his fate and asked for his corpse, they were told it would not be released because an apostate was not entitled to a burial. Most families were denied the remains of their loved ones and even the right to hold a funeral. The bodies were dumped in mass graves overnight to prevent public ceremonies, which could well have turned into riots. Had the families been able to mourn their loss, or had there at least been a headstone at which they could lay flowers, they might have moved on. But without either, time stopped in 1988, where they have remained in a fortress of grief.

Since that terrible summer, some of the victims’ families have been in search of justice. Many of them are immigrants and became autodidacts by necessity, educating themselves on human rights and the various organisations working in the field. For Bazargan, leafing through the grim rights groups’ reports about Iran became an obsession. In 2020, she happened upon Amnesty International’s 30th anniversary report commemorating the 1988 massacre, where she first learned that Mahallati had been Iran’s ambassador at the UN during the killings, and that he had justified the regime’s most indefensible positions.

When Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against the writer Salman Rushdie in 1989, Mahallati defended it. When he was asked about the arrest and execution of the Baha’i, a peaceful and nonviolent religious minority in Iran, he defended that too, falsely accusing them of “immoral behaviour” and “sexual abuse.” In a speech on the UN floor in 1989, he called “the Zionist entity” an Islamic territory, the “liberation” of which “was a great religious obligation.” And when he was questioned about the 1988 massacre by the UN’s special rapporteur on Iran, he described the victims as “battlefield casualties,” attributing their fatalities to the Iran-Iraq war, which in 1988 was in its eighth and final year. That he sought to cover up those crimes stunned Bazargan, but not as much as the discovery that he was living in America and teaching at Oberlin.

Bazargan teamed up with an attorney, Kaveh Shahrooz, whose uncle had been killed that same summer. Together, they drafted an email to Oberlin’s president, Carmen Twillie Ambar, in which they accused Mahallati of complicity in war crimes and demanded that his employment be terminated. Shahrooz was doubtful that their petition would move the college. But Bazargan was optimistic. She is a serious woman, and it was with great seriousness that she had taken her oath of citizenship, pledged allegiance to the US, and spoken the words “and liberty and justice for all.” With the email, she was seeking justice, as she had vowed to do as an American citizen.

III. The Protean Diplomat

After he left the United Nations in 1989, Mahallati found America to be an unsuspecting place. The glamour of his diplomatic career followed him everywhere he went, but somehow the ignominy of the government he had served did not. For ordinary Iranians who have suffered under the rule of their regime, their nationality is a liability wherever they go. But for a high-ranking official of that regime like Mahallati, it was an asset. The notion that he had been a spokesman for a regime accused of gross violations of human rights and acts of terrorism did not seem to concern the people he met.

Mahallati was not compelled to denounce or renounce the regime, nor was he expected to explain his association with it. If anything, he was an object of fascination, even to seasoned journalists, who penned wide-eyed profiles instead of taking him to task. This credulity allowed him to dream up a new persona for himself as a “scholar,” and the shapeshifting would have been seamless were it not for his poor record of publications. But here, too, he found a shortcut. He joined ILEX, the imprint of a Boston-based Middle East scholar named Olga Davidson, where he published several articles about peace, friendship, and poetry, reinventing himself as a Muslim Mahatma Gandhi with a dash of Rumi. Those self-published articles were later submitted to the Oberlin tenure committee to supplement the paucity of peer-reviewed papers he had published.

After a disastrous stint as a graduate student at Columbia University led to his dismissal in 1998 (more about which in a moment), Mahallati embarked upon a career as a consultant at several non-governmental organisations. One of these was Search for Common Ground, which is dedicated to peace-building around the world. Following the al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington on 11 September 2001, Search for Common Ground chiefly focused on the Middle East—especially Iran, where it hoped to avert a new war with initiatives that brought Iranians and Americans together. In 2002, the organisation invited several American university presidents to travel to Iran to help lower tensions through the pursuit of track II diplomacy.

One of the invitees was Nancy Dye, the beloved president of Oberlin at the time, who would be posthumously described as a “caring and engaged citizen of the world” by her successor. A career historian greatly respected for her scholarship in the field of feminism and labour in America, Dye was keenly aware of her lack of expertise on Iran and admitted to friends that she was “woefully unequipped” to make the decision to go. She was also apprehensive about “the bona fides and agenda” of Search for Common Ground. Some of the Oberlin board members had raised concerns about Dye’s security and the political fallout from the trip, especially since the organisation’s founder was a former state-department officer with US government ties.

Dye considered all this. In the end, she decided that the trip was an opportunity for Oberlin to become an academic flagship for peace and reconciliation with Iran. And so she went along. The trip was meant to be a first step towards creating an academic exchange program between the Oberlin conservatory and Iranian student musicians, intended to win the hearts and minds of all involved. In the photograph on her visa application to Iran, Dye is pictured smiling from beneath a scarf tied awkwardly around her head. In the blank space below the words “accompanying family members,” she printed “GRIFFITH R. DYE” in block capitals. In the box marked “Purpose of Visit to I.R. of Iran,” she wrote “Educational Cooperation,” though in the end, at sea in Iran’s complex political environment, Dye lost sight of that purpose.

The trip finally took place in 2004 and purportedly made Dye the first American college or university president to visit Iran in more than 25 years. She was received so warmly that she decided to return for a second visit in 2006. It was during those two trips that she met Mahallati, who was then working as a consultant for Search for Common Ground. His call to dialogue and friendship among all peoples and civilisations impressed her greatly and she decided to bring him to Oberlin, so that Americans could also be exposed to his message.

Like so many Western visitors to Iran in those years, Dye believed that there was no need for any American intervention in Iran because the country was on the cusp of a great change on its own. In the interviews she gave upon her return to the US, she spoke of how ordinary Iranians openly criticised their government. She concluded that the forces of evil—the hardliners—were at war with the forces of good—the reformists. All America needed to do was tip the balance of power towards moderation by supporting the reformists. She did not wonder if this tension was perhaps a charade, a political game of good-cop-bad-cop that the regime allowed to go on. Nor did she know enough about Iran’s power hierarchy to see that no meaningful change could come to Iran under its current supreme leader.

Her enthusiasm got the better of her. Forgetting her early apprehensions about her lack of expertise, Dye began befriending “reformists,” including Javad Zarif, who was then Iran’s UN ambassador, hoping to do her part to aid the forces of “good.” On her first trip, she had gone to pursue her own agenda of creating an academic exchange program. But on her second, she was a guest of the Organisation of Culture and Islamic Relations at a conference on “conflict prevention.” Mahallati was one of the key organisers of this government-sponsored event.

And so it was that, however unknowingly, Dye became a tool in the hands of the organisers and forsook her academic commitment to neutrality. That is why, at the conclusion of her two trips, and despite the grand ambitions she had once espoused, Oberlin never sent any students to Iran and Iran never sent any students to Oberlin. For all the effort and resources she spent on the cause of peace and reconciliation, the only tangible outcome for Oberlin was the addition of a new professor to the college’s roster of instructors—Mohammad Jafar Mahallati.

IV. The Nemesis Goes to War

By 2021, a year had passed since Bazargan had sent her email to President Ambar. She had heard nothing back. Now that COVID restrictions were finally being lifted and in-person classes were resuming, Bazargan thought that her grievances should be expressed in person. She chose a Tuesday, when Mahallati’s classes met, to stage a protest. The “1988 families”—named for the year of their shared tragedy—began to organise and circulate details of the protest in their communities.

On 2 November—a mild and sunny day, just as Bazargan had hoped—the protestors converged on the town from all corners of the United States. A mother, three of whose children had been killed in the summer of ’88, drove from Michigan. A young woman from Cleveland named Fatemeh Pishdadian, a research engineer at Apple, stood alone holding the framed portraits of her parents, who had been political activists as a young couple before their daughter was born. Her father was tortured to death before her mother gave birth to her in prison, where Fatemeh remained until she turned eight months old, just before her mother was executed.

Iranians are, by nature, a poetic people who find metaphors in the unlikeliest places. Upon learning that Oberlin had been a stop on the Underground Railroad during slavery, the protestors thought it an auspicious sign that they, too, were on their way to redemption. They had traveled there as pilgrims of justice, having brought their stories to the very college whose founding mission was “to save a perishing world.” On that day, all they were asking for was an audience with the administration and a chance to have their story heard.

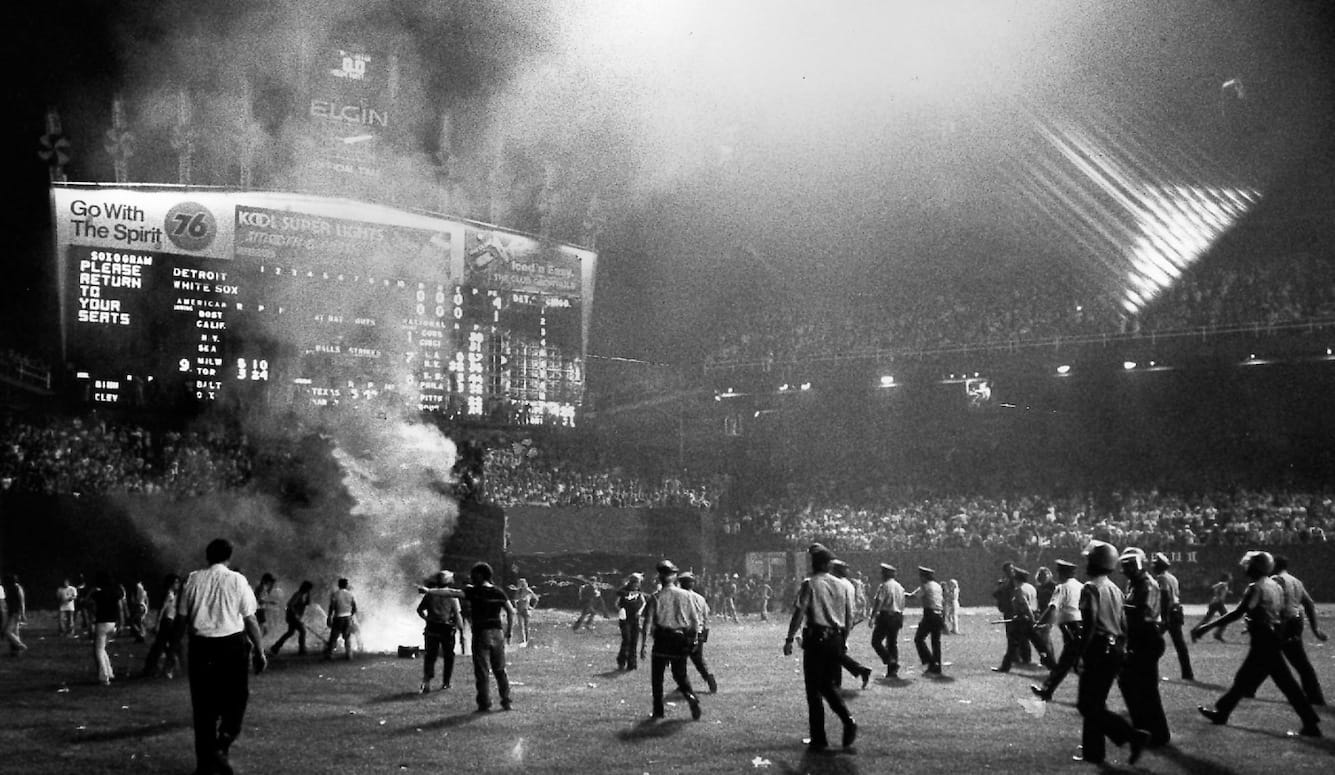

The 2 November edition of the student paper, the Oberlin Review, published a cover article headlined, “Evidence Against Mahallati Irrefutable.” After offering a damning indictment, the piece went on, “Iran has so successfully obfuscated its crimes against humanity—through mouthpieces like Mahallati and many others—that it has been able to continue perpetrating such crimes to the present day.” The moment was at hand for the college to show how the teachings of its Professor of Peace, Friendship, and Forgiveness Studies could work in the real world to help make amends with those who had come so far and who were so clearly injured.

But, once again, the administration remained silent. Revisiting the events of that day, one professor later recalled that the protest had been “a perfect teachable moment to talk to students about a very important era in Middle East history: Iran and Iraq in the 1980s, the war between them, the rise of Khomeini and the dramatic changes it brought to the region, and the violations of human rights on both sides, especially in Iran. But the college let that opportunity slip.”

Instead, Oberlin issued a factsheet that resembled a corporate statement drafted for the purpose of damage control. The college claimed it had “reviewed the [Amnesty International] report” and conducted “a series of internal conversations, including with Professor Mahallati, who denied the allegations. Through a law firm, Oberlin engaged professional investigators, who used their expertise to gather and evaluate information available from 1988.” The law firm—Greenberg Traurig LLP—had looked into the families’ claims about Mahallati, the statement went on, but had found no proof of the allegations.

Alas, the facts on that sheet proved slippery. Some of them were deleted within a few short weeks, just as Bazargan—whose name is now as feared at Oberlin as Voldemort’s is at Hogwarts—began looking for a copy of the report. She contacted the school and the law firm asking to see it, but neither responded to her request. Instead, the firm’s and the attorney’s names were scrubbed from the website—an omen of other erasures to come.

The incessant silence, the deleted names, and the missing report all began to make Oberlin’s stance look suspicious—the college’s behaviour resembled that of a used-car salesman dubious about the product he is promoting. Perhaps the college had released the factsheet in an attempt to appease the protestors, mistaking them for the student groups who come and go every four years, and whose demands ebb and flow with the demands of the academic seasons. But those who have not suffered a grave tragedy routinely underestimate the lengths to which real victims will go to get their due. These protestors had no ebb and flow. They were steady. And they knew only one season, summer, and only one year: 1988.

If the factsheet made anything clear, it was that the college had not really “engaged professionals” or properly “investigated” the matter at all. Had they done so, a few of those “facts” would have shown themselves to be either hyperbolic statements or outright falsehoods. In a letter to President Ambar disputing the allegations against him, Mahallati wrote, “I was in New York the entire summer of 1988, focusing on peacemaking between Iran and Iraq, and I did not receive any briefing regarding executions.”

However, even the popular historical accounts of that era demonstrate that this claim is untrue. The “Diaries and Report Card” of Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani—the 1988 Speaker of the Assembly who became president the following year—is a multi-volume set that spans his political career throughout the 1980s. And there, listed in the index of names, is the name Mohammad Jafar Mahallati. He is mentioned nine times, two of which are about visits Mahallati paid to the former president in August and September of 1988. According to Rafsanjani, Mahallati was in Tehran at least twice for meetings with the country’s top leadership in the heat of the killings.

Could the subject of a nationwide massacre of such magnitude have gone unmentioned in those meetings? Perhaps. But even if it did, it is difficult to imagine that the son of a major ayatollah, a Hojjatoleslam himself (a religious status only one step below an ayatollah in the Shi’ite hierarchy), never heard of the chasm that had suddenly divided the nation’s two most powerful clergymen: Ayatollah Khomeini and his successor-in-waiting, Ayatollah Montazeri. So vehemently did Montazeri oppose the killings that Khomeini dismissed him as his successor, thereby denying Montazeri the country's most coveted position of power. This stunning move was intended to make clear, according to the audiotapes of the meeting that were later leaked, that in his view, the massacre amounted to an unforgivable sin. Did news of the historic row that changed the course of Iran’s politics by paving the way for the rise of Ayatollah Khamenei to supreme leadership somehow miss the house of Mahallati?

Even if it did, one of the many press queries and special bulletins that Amnesty and other human-rights organisations were sending to Iran’s UN Mission about the killings surely reached the ambassador’s desk. There were also reports by the UN special rapporteur about the massacre, which prompted meetings between Mahallati and other UN officials in November 1988. And if not in 1988, Mahallati must have heard about those crimes in the following years when the subject became the centrepiece of high-profile political addresses by the late President Raisi, who had been a member of the committee that had overseen the executions. Mahallati could have condemned the massacre, as he was urged to do by his predecessor at the UN. But he never did. This would have been the perfect opportunity for a champion of peace to set an example for reconciliation by openly acknowledging the tragedy. It is where all the articles written about peace, all the friendship t-shirts sold, and all rainbow flags brandished were meant to lead.

Instead, Oberlin declared the matter closed and uncritically embraced Mahallati, allowing him to enjoy the privileges of professorship at an American college without relinquishing the privileges of complicity with Tehran. The silence he kept in America produced real perks in Iran. Each time he arrived, he cast off his professor’s suit, donned the clerical turban and robe, and slipped into his role as the son of the great Ayatollah Mahallati, taking charge of his father’s estate and charities.

If ever there was an academic who managed to have his proverbial cake and eat it, it was Mohammad Jafar Mahallati. Only the 1988 families—who had undergone the naturalisation process in the US and been asked countless questions about any past or existing affiliations with anti-American parties or groups—wondered how Mahallati had earned US citizenship, despite his diplomatic career and ongoing relationship with Tehran.

Throughout 2022, the families continued to stage protests at Oberlin but disillusion was creeping into their ranks. Bazargan knew she had to think of a new campaign—a way to bring the story back into the local headlines. It was at this point that she turned her attention to the title of Mahallati’s chair, which was named after Dye. What if, Bazargan wondered, President Dye had learned before her death of Mahallati’s history? Would she still have wanted her name and legacy to be tied to him? Bazargan contacted Dye’s widower to put this question to him. When she failed to get through on the phone, she drove to his house.

One day, Griffith Dye saw a woman pacing the cul-de-sac of his block. He stepped out to ask who she was. When she answered him, he called her “impolite” for showing up uninvited. Bazargan did not disagree. This was, after all, an unannounced visit to the home of a stranger. But what else could she do if he would not take her calls? She handed him a manila envelope filled with the various materials she had compiled on Mahallati and urged him to read them. They later exchanged a couple of letters. Eventually, worn out by her persistence, he asked her to leave him alone. Yet, sometime after these exchanges, President Dye’s name disappeared from Mahallati’s title, like so many other things about him that had vanished from the college’s website. At the expense of etiquette, Bazargan had scored a small victory.

V. The Professor: Unchecked and Unbound

By the end of 2007, Mahallati had already taught at Oberlin for a term, but he had yet to secure a permanent post. As none existed for him, the office of the president contacted Ben Schiff, a now-retired professor and one of the founding fathers of the Middle East and international relations concentrations at Oberlin. The president’s liaison told Schiff that he could have a special presidential fund to hire a faculty member for a year, but that the funds would only be made available if he hired Mahallati. Schiff told me that he found this offer peculiar. But he also thought that he could not afford to reject the president’s request. So he agreed.

Once the year ended, Schiff formally advertised the position. Mahallati applied, but his qualifications paled in comparison to those of other applicants. The tales of his time as a jet-setting diplomat did not impress Schiff, who was looking for a first-rate scholar and educator. Mahallati had very few publications, and his doctoral dissertation was nowhere near to being ready for print. Besides, his letters of recommendation were mostly from non-academics. Schiff, one of the few professors who had not joined the cult of Mahallati, rejected his application. So, Mahallati returned to the religion department, where his staunchest ally was chair.

Unlike Schiff, most of Mahallati’s colleagues overlooked his shortcomings, even when those shortcomings violated the standards to which they held each other. For instance, the faculty at the religion department had always understood that they were expected to keep their own religious beliefs out of their classrooms. Instead, they were to cultivate a sense of inquiry among their students. They were not to proselytise, but to equip the students with the critical skills to understand, analyse, and question religion. They knew that, if done correctly, such an education could, in fact, be a subversive exercise that might even produce atheists and agnostics. Nevertheless, even the believers among them did just that.

However, the same rules did not apply to Mahallati. The faculty knew that teaching for him was a form of Shi’a advocacy, but they were unwilling to confront him about it. Mahallati’s partiality had, indeed, come up in the department, especially in the later years, when the time came for his tenure consideration. When I spoke to Abraham Socher, a now-retired professor who had long taught at the department, he recalled those conversations with his fellow professors. “Some of us were concerned that his approach was uncritical, closer to old-fashioned religious apologetics than modern academic scholarship,” he told me. “The rest of us were trying to help our students understand the religious traditions we taught—using the tools of history, philosophy, anthropology and so on—not promote them. A colleague, a professor of Buddhism, hit on an answer that he repeated several times to me and to others, ‘given the politics of post-9/11 America, Mahallati’s advocacy was okay, because it countered the public bias against Islam.’ I never agreed with this double standard, but it became, more or less, the official position of the department.”

In response to what they believed to be Islamophobia in the United States, Mahallati’s colleagues were leaving him free to do as he wished, even when his behaviour violated their own protocols. Mahallati was no longer a person to be judged by his actions. He had become a human totem before whom college “progressives” could display penitence for whatever wrongdoing they believed America had committed. To undo what they believed to be one sin, they were committing another, and they could not see that giving one Muslim a free hand was as wrong as violating a law-abiding Muslim’s rights elsewhere.

Meanwhile, in Iran, Mahallati publicly boasted of his proselytising in America. In a Persian-language podcast, the interviewer asked him if Oberlin students ever told him that they found Islam attractive and wanted to convert. Mahallati answered that, yes, this happened frequently. Every year, he told the interviewer, one or two out of his 100 students were ready to receive “the honour of converting to Islam,” something he helped them achieve.

Much is always lost in translation. When Mahallati addressed Persian-speaking audiences, it was his pretence of religious pluralism that disappeared. In a letter to an Iran-based publication—an appeal to his critics and detractors inside the country—Mahallati spoke openly of the Sunni versus Shi’ite rivalry in the United States and warned that the Saudis were gaining the upper hand in promoting their brand of Islam at American universities. “The Saudi Prince,” he complained, “promising pricey Bentleys to the Saudi fighter pilots who bomb Yemen, has also endowed eight chairs in Islamic Studies at Harvard and Georgetown. At this moment, many students pursuing Islamic Studies at these universities naturally take their influences from the founders of these positions. It’s staggering that amid all this, a group in my beloved homeland is trying to stymie the 2–3 Iranian-Shi’ite professors who are working in the field of Islamic Studies.”

In a 2011 article for an Iranian publication, Mahallati wrote of a “historic opportunity” for Islam, which was fast spreading in North America. This unprecedented momentum, he believed, could pave the way for a powerful new Islamic civilisation on this continent. However, he worried that this inevitable triumph would only benefit Sunni Islam if the Shi’a did not intervene. “If there is no ‘positive interaction’ between the Shi’ite world and the West,” he wrote, “... the share of Shi’ism … may be none at all.” Was all his apparent enthusiasm for peace and friendship at Oberlin simply a way of creating a “positive interaction” to further his religious agenda? Was peace not an end, but a means to a wholly different end that his American audiences were too naive to recognise?

Judging by what he said and wrote in Persian, Mahallati had never really given up his ambassadorial role. But at Oberlin, he was free to launder Tehran’s worldview as disinterested scholarship. At the inaugural event of his much-touted “Day of Friendship” initiative in the town of Oberlin, he gave a fervent speech in which he spoke of friendship as a defence against “America’s chief export to the world—weapons of war.” His rhetoric may have sounded anodyne but it rang with the same anti-Americanism of the imams at Friday prayers.

VI. The Professors’ Enablers

In his timeless book of essays, On Repentance, Michel de Montaigne observed that when a person takes a step towards vice he rarely stops. The same applies to the enablers of those who commit that vice. Once a special provision was made for Mahallati in the religion department at Oberlin, further provisions soon followed as he breached other college rules and standards. One such breach occurred in 2013, when one of Mahallati’s advisees, a 20-year-old Muslim student from a small Arab nation, visited him during his office hours. She told me that she had taken a class with Mahallati the previous term and felt some kinship with him as a fellow Muslim. In a foreign land for the first time without her family and community, she found in Mahallati the familiar things she missed about home. So, she chose him to be her capstone project advisor.

When she met with him to discuss her project that day, she was wearing a dress. Alone with him, she recollected, Mahallati had gestured at her and said that “it’d be easy for me to find a man in that dress.” Other inappropriate remarks made her so uncomfortable that she excused herself and left immediately. The encounter disturbed her. It took a few days and the encouragement of another professor in whom she confided before she spoke about the incident with the head of the department. He listened, but rather than advising her of her rights as a female student facing sexual harassment or taking disciplinary action against Mahallati or formally reporting what she had told him, he made light of the matter. All she needed, he said, was a different advisor for her project. He assigned her to someone new. From then on, the joy of her first days at Oberlin gave way to apprehension. The college that had been established in 1837 to welcome women violated its own founding principles in 2013.

Had the department investigated the incident, they might have uncovered other concerning facts about their unimpeachable professor. So, Bazargan did what the college would not. With the help of an investigator, she searched the legal databases and found a 1998 sexual-misconduct lawsuit in the New York federal court filed against Mahallati. The plaintiff was his former student at Columbia University, who alleged that he had traded grades for sexual favours and then blackmailed her into silence.

Mahallati had tried to dodge the suit at first by claiming that, a decade after leaving the UN, he still worked as a consultant for the Mission, and was therefore protected by diplomatic immunity. But when Columbia University administrators tried to verify Mahallati’s claim, the State Department responded, in a letter dated 9 February 1998, that “Mr. Mahallati is not currently a diplomat and thus does not enjoy a general immunity from the jurisdiction of U.S. courts.” The case was eventually settled out of court, and the student received monetary compensation in exchange for a non-disclosure agreement, though an Arab newspaper had already reported the story.

Harassment allegations against Mahallati long preceded the incident at Columbia University. An article in the London Times on 17 April 1989 reported that Mahallati had been dismissed from his post at the UN, recalled to Tehran, and charged with “corruption,” for apparently having “associated with unrelated women.” Perhaps the charge was trumped up, like so many other false charges the regime has brought against those it has arrested and imprisoned. But given Mahallati’s history, Tehran’s allegations seem like another episode in a pattern of misconduct.

At Oberlin, however, where scholars of Iranian history were not around to challenge Mahallati’s accounts, history was what he recounted. When he painted himself as the lone crusader for peace between Iran and Iraq who was later fired for his efforts, Oberlinians believed what they heard. In fact, Mahallati was not the only person cast aside in 1989. His superior, Mohammad Javad Larijani, the deputy minister of foreign affairs, was also ousted. Khomeini had died, and a massive shift in power had followed. As in most instances of the changing of the guard, some lesser political figures rose to the top while others sank.

Yet, Oberlinians continued to celebrate Mahallati as the “architect of peace” between Iran and Iraq, even though the sole source and all the supporting evidence for that claim was Mahallati himself. Unlike his students, Mahallati could make any assertions he liked without offering evidence. In a statement written to accompany the college’s factsheet, his attorney argued, “Because many Iranian leaders uncompromisingly pressed for a military solution, Mahallati’s diplomatic measures brought him under heavy domestic criticism, which remarkably continues until today. Being accused for going beyond his official mandate for pressing for peace, he was dismissed in the spring 1989 and amid his regular four years tenure.”

In reality, however, Mahallati had been one of a dozen or more senior diplomats involved in the negotiations, most of which convened at the UN headquarters in Geneva, not in New York. His main role is described, especially in the diaries of Rafsanjani—who was the Chief of Armed Forces at the time—as that of an administrative liaison, who took Tehran’s messages to the UN’s top officials and vice versa. Besides, during the years that Ayatollah Khomeini was alive, his hold on Iran’s politics was ironclad. He had been the sole decision-maker on all matters of great consequence, the agreement to end the war with Iraq among them.

A year after the incident with the Muslim student, Mahallati came up for tenure consideration, and the allowances that had been repeatedly made for him were made again. Though his publications in peer-reviewed journals were fewer than the department had required for tenure consideration in the past, an enthusiastic committee convened to deliberate on his promotion. His online professor reviews were generally positive and occasionally effusive (“The instructor was amazing, inspiring, wise, and insightful,” wrote one student). But reading between the lines, it is possible to infer that some of these students thought his class offered an easy A-grade.

His lectures were more like story hours without much in the way of teaching, and they demanded little from the students in return. In the eleven-page report the committee received, a few student comments should have given everyone pause: “Some students saw the stories as sidetracking from the course content, tangential, or repetitive. Still, other students recognized Mahallati’s use of stories and personal experience as a non-Western pedagogical style that required students to ‘navigate his meaning.’ While most students thought the workload he assigned was appropriate and rated their own learning quite high, a few commented on a lack of rigor or a lack of clarity and feedback in assignments.”

One comment, in particular, ought to have alarmed the committee. A student—an American who, unlike her Muslim peer, was familiar with the codes of conduct and her own legal rights—had reported, “In my one-on-one sessions with him, I’ve found that he’s said some really sexist remarks, some of which constitute sexual harassment and grounds for a Title Nine violation. He also expected me to help him with his extracurricular pursuits and this felt very manipulative while I was taking his classes, when he controlled my grades.”

But the authors of the report downplayed that student’s comment by adding, “We note that this is the only such comment among all of his teaching evaluations and among the 73 respondents to the survey.” As Mahallati had become a symbol to the faculty, every reason for concern, however serious, was treated as negligible. Mahallati was granted tenure.

VII. Oberlin: Good Intentions Gone Wrong

In November 2023, I sat in a humdrum fluorescent-lit conference room at Oberlin for a meeting with the college’s director of media relations. I had come to speak to Griffith Dye and several members of the faculty and administration, including Mahallati himself. While many retired professors did agree to talk to me, those who were still employed by the college never responded to my interview requests, and the few who did would not speak to me on the record. During my conversation with the director, I learned that all my interview requests had been forwarded to her. She was adamant that, since I had been a co-signatory to Bazargan’s 2020 email to President Ambar demanding the ousting of Mahallati, I could not be an objective reporter on a story about him.

I agreed that I was not objective about Mahallati. However, I explained that I had not come to Oberlin to discover who he was. Most of what I needed to know about him I had already gleaned from Persian-language sources. The focus of my inquiry was not him, but the college. I wanted to understand how he had risen to become a professor and how he had remained in that post there despite his shortcomings and wrongdoing. I wanted to know why a group of serious scholars had so vehemently defended a man whom they had every reason to doubt. I wanted to know why they had made so many exceptions to accommodate him that they would not have made for each other. Most of all, I wanted to know what had made an institution like Oberlin vulnerable to a man like Mahallati? The director listened to me and promised to consider my request for the interviews. We parted politely, though I knew not to hold my breath.

Bazargan traveled to meet me at Oberlin and we spoke for several hours. She gave me a full account of her efforts and spoke of the frustration she and the 1988 families were feeling. Some locals, born and raised Americans, were now staging counter-protests in defence of Mahallati. They carried signs that read, “Stop Political Racism” and accused the protestors of anti-Iranian and Islamophobic sentiments, even though the protestors were all Iranians and Muslims. Why were these people—who could not study the sources the families were citing, who had never set foot in Iran, and who did not understand the complexities of that country’s history and politics—allowing themselves the certainty that Mahallati was the one whose rights were being violated, as opposed to the people whose family members had been killed and buried in nameless graves?

The families’ frustration knew no end. They felt frustrated because the college had rejected them. They felt frustrated because the very officials who had been in power in Iran, and from whom they had fled to America, had risen to positions of power in America. Was Mahallati not a perfect example? When the college and the local counter-protestors looked at him, they saw only one man, while the protestors, who were able to read Mahallati in Persian, saw two.

On my last day at Oberlin, I tried to meet with anyone who knew something about the case, including some councilmen and councilwomen. They all enthused about the great virtues of Mahallati’s annual Day of Friendship, although they did not have much to remember it by besides the peace T-shirts. One former councilman, who considered Mahallati a friend, spoke of him as an Iranian Salman Rushdie: an indomitable dissident against the regime who, because of family considerations, was not able to voice his opposition to the regime. The councilman was a retired employee of the college with a longstanding record of service to the community. I asked him why he was willing to stake his reputation on a man whose life, thoughts, and work were mostly written in a language he does not speak or understand. The certainty in his face was briefly eclipsed by panic, and then he muttered that he would have to think about my question.

Like my compatriots, I looked for a metaphor for the story I had come to report as I wandered around the town’s historic Tappan Square, and I found it in the town’s humble and historic Gibson’s Bakery. In 2015, three black students had tried to shoplift from the store but were stopped by the Gibsons’ grandson. Rather than subject the students to disciplinary action, the college accused the store owner of racial profiling. The family were wronged by the students and then by the college, and what they went through resembled what Bazargan and the other 1988 families were going through now. In both cases, the perpetrators were presumed innocent despite copious evidence to the contrary. A constellation of inverted principles had prevented any real inquiry into what the Gibsons or the 1988 families had suffered. Oberlinians had relinquished their duties as sceptics, scholars, and sensible community members to defend what they thought to be a just social, political, and racial cause. In both cases, the facts had not mattered at all, only the race or religion of those involved.

Mahallati is not the first professor from a hostile nation to be employed by an institution of higher learning in America. After World War II, many German scientists and academics, some of whom had been members of the Nazi Party, began teaching at American universities under assumed identities. During the Cold War, scholars and scientists from the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc became university professors in America after they defected from their homelands. In the wake of the Cuban and the Iranian revolutions, a number of professors and professionals fled their respective countries and resumed their careers here. But in every past instance, they had renounced their old ties and allegiances before entering their new positions. What is the precedent for those who continue to serve as the mouthpieces of adversarial powers even as they are entrusted with the task of educating America’s youth?

As early as 1990, Iran’s former minister of intelligence, one of the founding fathers of the country’s terror apparatus, said in an interview that he uses every cover possible, especially the cover of journalism and other fields like it, to infiltrate and gather intelligence from other countries. More than thirty years later, Iranian agents have tried to carry out assassinations on American soil. In early June 2024, in the aftermath of the protests and encampments on college campuses, Iran’s supreme leader praised America’s students for “standing on the right side of history.” In early July 2024, America’s director of national intelligence Avril Haines issued a statement warning that Iran was influencing and funding the protests on America’s campuses. For decades, the United States has been chiefly focused on curbing Iran’s nuclear ambitions. Meanwhile, Iranian actors have successfully penetrated America’s academic and civil society at large, sowing division, wreaking chaos on campuses and hatching plans for assassinations.

The decision to place Mahallati on “indefinite leave” in late 2023 arrived shortly after the 1998 sexual harassment lawsuit surfaced and just as a congressional inquiry into Mahallati’s antisemitic statements was launched. Although he is no longer on campus, there has yet to be a process of accountability or much introspection about how a community ostensibly committed to learning can place ideological dogma ahead of thoughtful scrutiny.

Such an exercise might provide Oberlin with a second opportunity to turn the ignominious record of a 13-year-folly into a teachable moment for everyone. It would allow the college to lead by example and show how one can reflect upon and correct past errors. While the college’s 21st-century heirs seem to have committed themselves to the misguided pursuit of fashionable orthodoxies, its early 19th-century Christian missionary founders had something else in mind entirely. They built a place where everyone, regardless of race or gender, could get an education. Now it is Oberlin’s chance to look within and restore those founding values.

In the end, Mahallati’s significance is tangential to what unfolded at Oberlin during his tenure. Liars, opportunists, and predators have lurked on campuses before, and they will do so in the future. The story of Mahallati is, in great part, about the way our open American hearts and minds, our pluralistic values, our embrace of other traditions, religions, and cultures can be exploited by those whose ambition is to remake us in their own image, dismantle democracy, and bring about our downfall.

I asked the former president of Oberlin, Fred Starr, whose tenure preceded that of Nancy Dye, where he stood on the matter of Mahallati. He summarised the college’s handling of the case like this: “In appointing, promoting, and defending Mr. Mahallati, Oberlin College tore down firewalls that protected this once noble institution for nearly two centuries: careful faculty oversight of all appointments, presidential responsibility, and, above all, the trustees’ legal and fiduciary duties. As they did in the notorious Gibson case, Oberlin’s trustees rejected educational leadership and engaged instead in legalistic gymnastics. The situation demands full disclosure and institutional soul searching at many levels.”

Before I left Oberlin, I met with Bazargan to ask her a final question. I wanted to know what she would ask of Mahallati were she able to make a single request of him. Without hesitation, she gave an answer that has haunted me ever since: “Tell us where the bodies are buried.”