Communism

Where Virtue Meets Terror: A Brief History of Proto-Communism

In a new book on the history of communism, Sean McMeekin traces the movement’s roots to egalitarian creeds embraced throughout history by prophets, philosophers, utopians, and serfs.

Communism as a ruling doctrine is a relatively recent phenomenon in historical terms, dating back just over a century—or, if we count parties bearing the name, such as the Communist League of Marx and Engels (c. 1847–48), about 175 years. But the idea of material or social equality lying at the heart of Communist theory traces back deep into antiquity, and it is worth examining the different strands of thought that have informed and inspired modern Communists.

In The Republic (c. 375 BC), Plato has Socrates observe that the proliferation of “such words as ‘mine’ and ‘not mine’ and ‘someone else’s’” must lead to the dissolution of the social fabric. By contrast, the best-governed city would be one in which “all the citizens rejoice and are pained by the same successes and failures,” as the “sharing of pleasures and pains bind[s] the city together.” A thoughtful ruler, or philosopher-king, should thus establish a kind of political equality among active citizens, who, by sacrificing selfish interests, would come to equate their own fortunes with those of the polity to which they belonged.

In his wicked satire Ecclesiazusae (Assemblywomen, c. 391 BC), Aristophanes went further, with his false-bearded female philosopher-queen Praxagora vowing to make “land, money, everything that is private property, common to all.” This dictum, she said, would include sexual relations: men must court the “ugliest and most flat-nosed [women]…side to side with the most charming [women],” and women were enjoined not to “sleep with the big, handsome men before having satisfied the ugly shrimps.”

Speaking to the individual soul rather than to the Greeks’ pagan philosopher kings, Jesus warned followers soon known as Christians that it would “be easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven,” and he advised one wealthy petitioner, who asked him what he must do to attain eternal life, “If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess and give to the poor.”

Generations of Christian saints, inspired by the example of Martin of Tours (AD 316–97), who died on a bare floor clothed in rags, have taken Christ’s words to heart, renounced their material possessions, and devoted their lives to helping the needy—to charity, as we now call it. As Saint Martin himself preached, a true Christian must act as “the helper of the lowliest, the protector of the weak, the shelter of the hopeless, the savior of the rejected.” In this way, early Christians introduced to the world the novel, counterintuitive idea that the weak, the poor, and the humble had as much human value as great statesmen, mighty warriors, and their wealthy patrons. If Christ was right, the meek might even find true salvation in the afterlife, while the selfish rich were judged and suffered the torments of the damned.

While not every believer has obeyed this radical precept to devote their lives to helping the poor or become poor themselves, the Christian idea of material renunciation added a powerful allure to the Platonic ideal of a collective-minded political community. People might not be equal in wealth or social status, but in the eyes of God all souls might be equal, or at least judged by a universal moral standard to which all were equally bound.

Still, even at its most radical, Western Christianity has stopped short of advocating outright equality of wealth and material differences as proposed by Plato and Aristophanes (the latter satirically). The rich might be judged by God and found wanting; but not even the most devout Christian theologians have proposed, like Robin Hood, to rob them and redistribute their wealth in order to level out the social order. Theft is, indeed, expressly forbidden in the Ten Commandments of the Old Testament (“Thou shalt not steal”), fundamental to the faith of both Jews and Christians. The embrace of poverty, or the practice of charity, for a Christian believer, is the conscious act of a free human soul, not a coercive act or something to be mandated in law.

Nonetheless, there is no denying the explosive implications of the Christian faith for social evolution in the direction of greater social equality. The story of Genesis, of an unclothed Adam and Eve in the “Garden of Eden,” central to both Judaism and the Christianity which emerged from it, posits a lost innocence or paradise. The first couple’s sin leads to the need for clothing to conceal the human body, has implications for the temptations and complications of sex, and foreshadows the greed of humanity that leads in turn to inequalities of wealth, and ultimately to the sundry evil acts plaguing the fallen world. These evils then must be proscribed by the moral lessons of the Ten Commandments and by the other laws and holy texts of the three monotheistic faiths.

Implicit in the idea of an earlier fall from grace is the possibility of redemption, whether through the restoration of a lost world or the repentance of an individual for their actions. History thus proceeds inexorably in the Judeo-Christian worldview toward judgment and redemption (or everlasting damnation). Christianity and Judaism differ in the pacing of the linear progression, with Christians generally believing more strongly in the idea of a final judgment for all mankind, a branch of the faith known as eschatology.

The central point, for understanding the evolution of Western intellectual life and ideas, is that the arc of time for Jews—and more especially Christians—moves forward in a linear fashion from one dramatic point toward another, with each decision, each action and event, pregnant with meaning in a world ruled by a unitary deity (God), rather than in random or cyclical fashion, or via the continual (though inconsistently paced) revelation of the sages and sagas of a polytheistic faith such as Hinduism. From the stories in the Bible to modern-day literature, this set of ideas has given Western thought its great narrative pull, as saints, poets, philosophers, novelists, and historians have wrung drama and meaning out of individual and collective struggle.

Islam, born of the same Abrahamic monotheistic tradition as Judaism and Christianity, shares the ideal of the equality of believers, and has its own ideas about how they will be judged worthy of heaven—or suffer eternal damnation. The Islamic tradition places less emphasis on voluntarism and free will in determining how believers (and unbelievers) are judged, ascribing all of the proceedings of human life, even those that take place while we are unconscious, to an all-powerful God, or Allah. As revealed to Mohammad in the Koran, “Allah takes the souls unto Himself at the time of their death, and that which has not died in its sleep. He keeps those on whom he has decreed death, but looses the others until a stated term.” The upshot is that, while Islam rejects fatalism, events are not random. Although time, for Muslims, is not cyclical, nor does it proceed with such inexorable forward momentum as it does in Christian thinking.

The eschatological and egalitarian impulses in Christian thought received a further shot in the arm with the (accidental) discovery of the New World after Columbus’s famous voyage of 1492. When European Christians encountered more “primitive” peoples, it was perhaps natural that these “native” Americans were viewed as pre-Revelation innocents who lived in an unspoiled garden like that of Eden (although, after the arrival of Europeans, it would not remain unspoiled for long).

Columbus himself claimed to observe, of the native inhabitants of what are now the Bahamas, Haiti, and Cuba, in his letter reporting to King Ferdinand of Spain, who had sponsored his voyage, that “all go naked, men and women, as their mothers bore them, although some of the women”—like Eve—“cover a single place with the leaf of a plant.” Economic and social innocents, too, these inhabitants of the New World were, according to Columbus, “so guileless and so generous with all that they possess, that no one would believe it who has not seen it. They refuse nothing that they possess, if it be asked of them; on the contrary, they invite any one to share it.”

Columbus was, of course, defective in his understanding of the peoples he encountered, whose languages he did not speak, and whose societies were far more sophisticated and socially differentiated than he assumed. But the excitement born of his discovery of such radically different cultures, however much may have been lost in translation, inspired a whole new tradition of Christian writing about New Worlds that might be less corrupted, less fallen, than the Europe they lived in. The archetypal example, which gave its name to the genre, was Thomas More’s Utopia (1516). More presents a strange but oddly compelling vision of a society without money, law, or lawyers, where economic activity is rationally planned by “magistrates who never engage the people in unnecessary labour.”

“The chief end of the constitution,” he wrote, “is to regulate labour by the necessities of the public, and to allow all the people as much time as is necessary for the improvement of their minds, in which they think the happiness of life consists.” And yet social equality remains distant in More’s utopian society: slavery is allowed, and we are told that “wives serve their husbands.”

The Christian Reformation, launched by Martin Luther when he posted his famous “Ninety-Five Theses” on the door of the church at Wittenberg in 1517—the year after More’s Utopia was published—also spawned radical visions of the remaking of society. Luther’s critique of the Church’s material corruption was radical enough, proposing a more democratic “priesthood of all believers” in place of the increasingly ornate hierarchy of the Catholic Church, which was financed by taxes (the tithe) and the sale of “indulgences.” Nonetheless, Luther balked at the idea of overturning the social order, disowning, and then denouncing, the German Peasant Rebellion of 1524–25 in a bluntly titled polemic, Against the Robbing Murderous Hordes of Peasants.

Other Reformation thinkers were willing to go further. Jean Calvin (1509–64) and his followers, in service of their belief in the predestination of human souls for heaven or hell, created a number of small, tight-knit communities defined by austere morality and principled renunciation of materialism, most famously the Republic of Geneva, which would inspire Jean-Jacques Rousseau (discussed below).

Still more extreme were the Anabaptists, who seized control of Munster in February 1534. Inspired by the idea that not only faith, but even baptism, should be a matter of individual conscience and free will—that is, left to the discretion of rational adults, rather than imposed on infants too young to understand the ritual—Anabaptists were already radical by Reformation standards, with many of them participating in the German Peasant Rebellion.

Given the chance to reorganise society in Munster, one Anabaptist sect, led by a former baker of Dutch origin named Jan Matthys, began by cleansing Catholics and Lutherans, then seized all the gold and silver in the town, looted Catholic monasteries of their wealth, abolished money, and declared food stocks common property. The radical new social order was enforced by terror, with public executions of critics, and by the edict that all houses keep their front doors open, so as to ensure that no private space be allowed for dissent.

In this frenzied atmosphere of enforced social conformity, all books other than the Old and New Testaments were banned, and then collected and burned in great public bonfires. Matthys’s ever-more-radical Anabaptist commune lasted about six weeks, until the tyrant of this theocratic utopia was cut down in battle and dismembered in early April—on Easter Sunday—with his head erected on a pole above the town to discourage future radical experiments.

Not all “utopian” thinkers, of course, wanted to set history’s clock backward to simpler times in the manner of Calvinists and Anabaptists. In New Atlantis (1626), Francis Bacon dreamed up a world enriched by the systematic study of plants, animals, and the heavens, enabled by the construction of observatories, nature parks, fish pools, and experimental facilities for agriculture, along with “brewhouses, bake-houses and kitchens.” Inspired by Bacon and the tinkerers who ushered in Europe’s scientific revolution, Denis Diderot and Jean d’Alembert set out to “assemble all the knowledge scattered on the surface of the earth” in a great Encyclopédie (1751–72), so that, in Diderot’s words, “our descendants, by becoming more learned, may become more virtuous and happier.” In this way the Enlightenment rationalism of the philosophes secularised Christian eschatology, establishing a kind of European religion of social progress.

By separating divine revelation from reason, however, the philosophes also forfeited much of the beauty and power of the Christian faith while also shunting Christian ideals about virtuous poverty and charity to the side. The hyper-rational “republic of letters” envisioned by Diderot, d’Alembert, and the famously irreligious Voltaire in the Encyclopédie was elitist rather than democratic, appealing more to enlightened despots, such as Frederick II of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia, than to ordinary Christians, or even the growing numbers of literate Europeans.

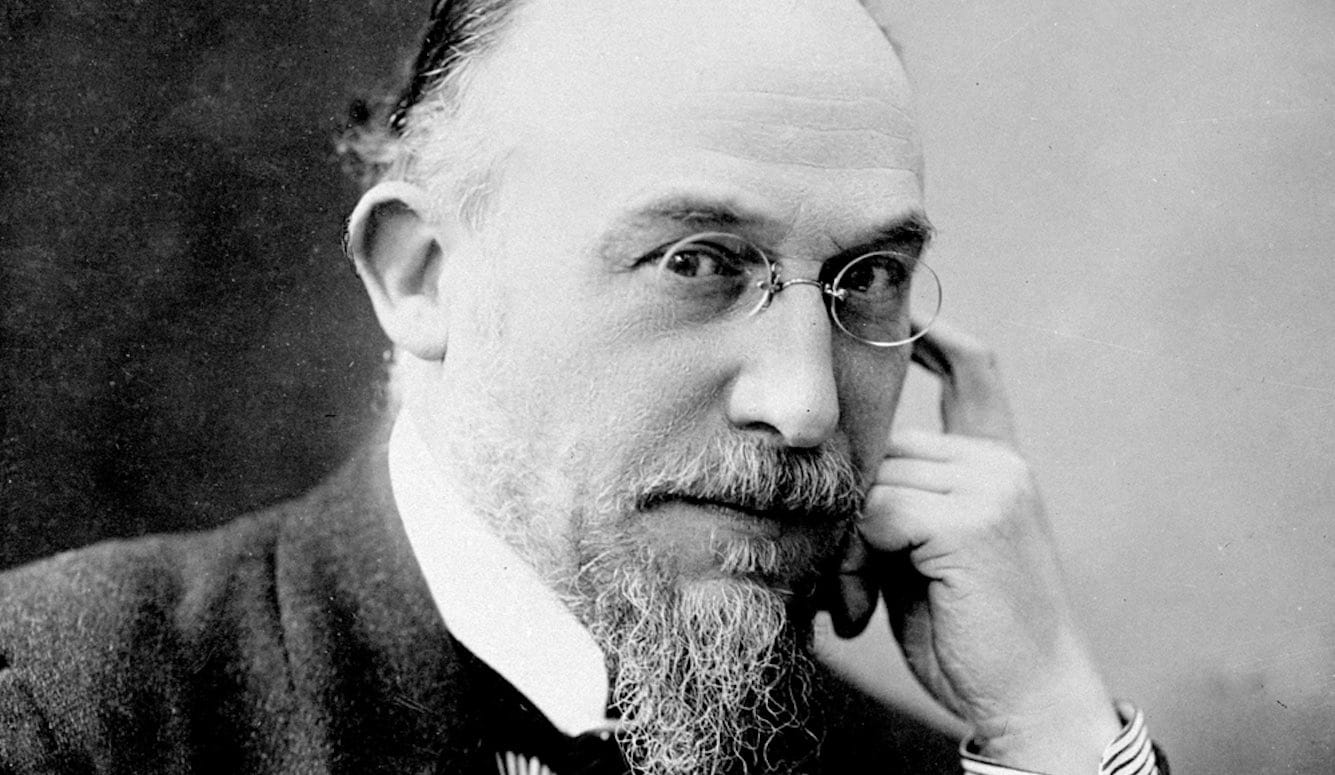

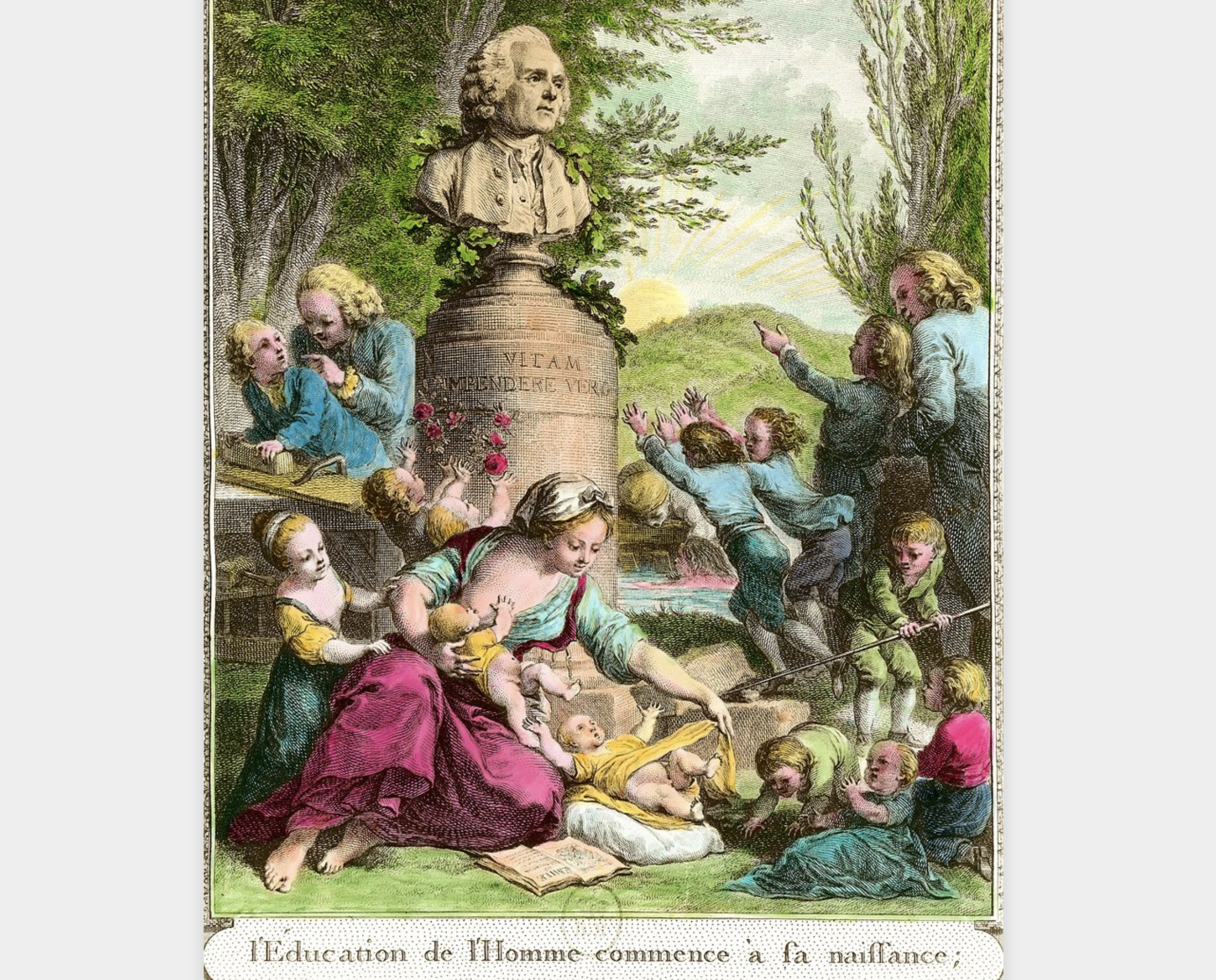

In the end, it was the skeptical enfant terrible of the French Enlightenment, the Genevan autodidact and itinerant tutor Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78), who left behind the era’s most enduring vision of social equality. Only in a “happy and tranquil republic,” Rousseau argued in his Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality Among Men (1755), could humanity avoid the corruptions that led to the “different privileges enjoyed by some at the expense of others, such as being richer, more honoured, more powerful than they, or even causing themselves to be obeyed by them.”

Like Christian saints and Columbus misinterpreting American natives (whom Rousseau revealingly described as “savages”), he looked back to a mythical lost Eden. Unlike Bacon and the philosophes, he did not believe that reason and scientific “progress” would improve lives. “The more we accumulate knowledge,” Rousseau warned, “the more we deprive ourselves of the means of acquiring the most important knowledge of all.” Civilisation and material improvement were morally corrupting, depriving people of their natural freedom, entrenching inequality and slavery, and rendering men selfish and ambitious.

“The first person who, having enclosed a plot of land, took it into his head to say, ‘This is mine,’” Rousseau surmised, “and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society. What crimes, wars, murders, what miseries and horrors would the human race have been spared, had someone pulled up the stakes or filled in the ditch and cried out to his fellowmen, ‘Do not listen to this imposter. You are lost if you forget that the fruits of the earth belong to all and the earth to no one!’”

In this celebrated passage, Rousseau came as close to the vision of a propertyless world of social equals as any thinker had done since Plato and Aristophanes. But he did not repudiate private wealth entirely, recognising that “the idea of property… was necessary to make great progress, acquire many skills and much enlightenment, and transmit and augment them from one age to another.”

In the famous opening of his 1762 work On the Social Contract, Rousseau proclaimed that “man is born free, but is everywhere in chains”—but his programme for liberating them did not include the abolition of private property. Rather, “in accepting the goods of private individuals,” a justly organised community “assures them of legitimate possession.”

Rousseau did insist that “each private individual’s right to own his own land is always subordinate to the community’s right to all,” and thus conditional on one’s civic status. As Rousseau explained in his most notorious passage, in order for any “social compact to avoid being an empty formula, it tacitly entails the commitment—which alone can give force to the others—that whoever refuses to obey the general will [volonté générale], will be forced to do so by the entire body.” By “violating the laws” of the community, such a “malefactor” must be “put to death,” Rousseau argued, “less as a citizen than as an enemy.” Nonetheless, as long as a citizen obeyed the laws embodied in the “general will” of his political community, his right to own property was upheld. Radical republican Rousseau might have been, but he was not, quite, Communist.

As Rousseau explained in his most notorious passage, whoever refuses to obey the general will (volonté générale) will be forced to do so by the entire body.

A large part of the reason Rousseau’s works became a standard part of the Western educational curriculum is that they so clearly influenced the course of the French Revolution. Rousseau’s idea of the “general will,” a nebulous notion of consensus public opinion or mandate he never quite defines in the Social Contract—there is no implication that it need reflect an actual democratic vote—made it into Article 6 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen passed by the French National Assembly in August 1789 (“Law is the expression of the general will”), to which all other clauses are subordinated.

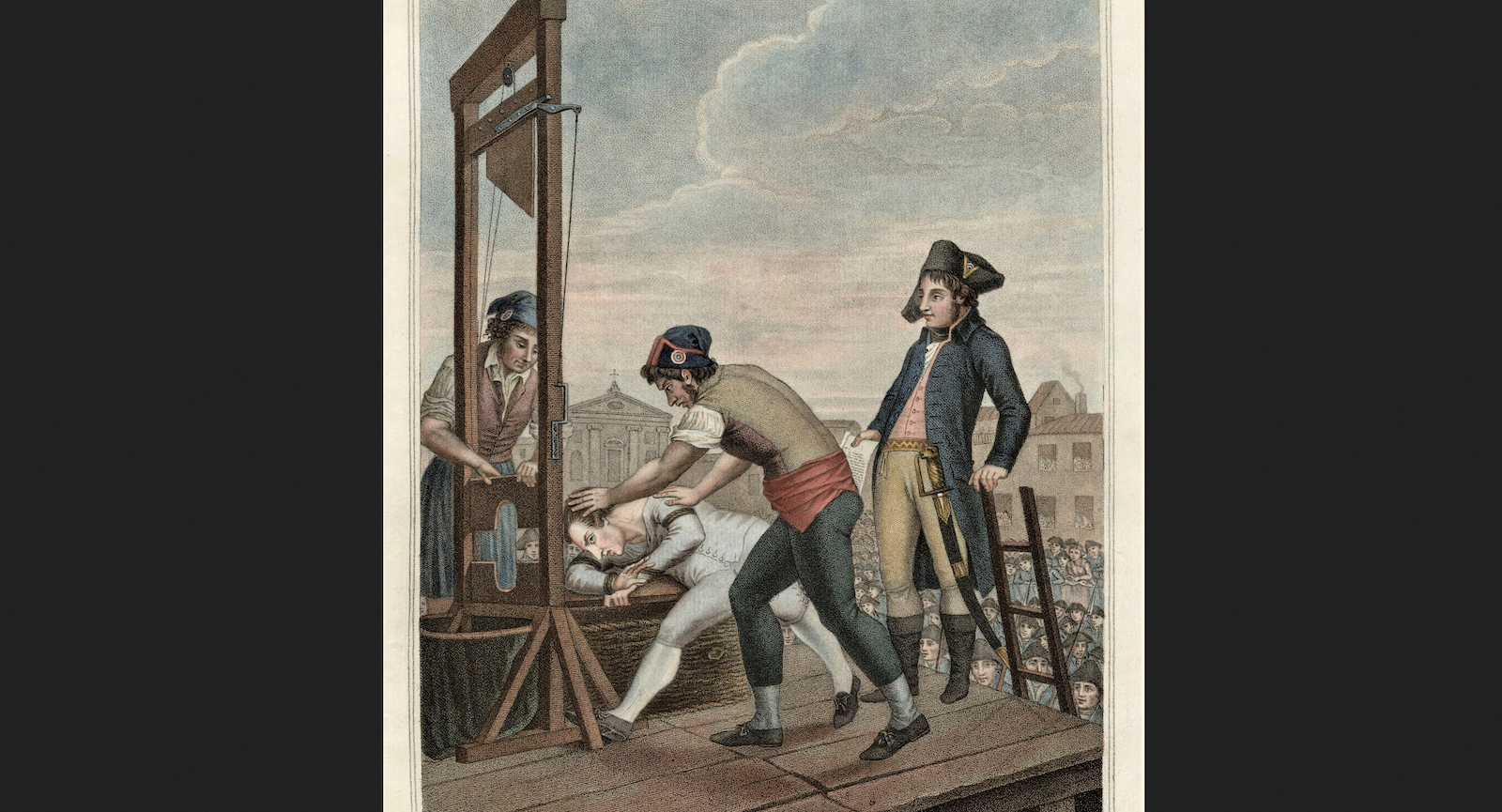

In the language he used to justify the “Terror” of 1793–94, Maximilien Robespierre channelled Rousseau’s views on the purging of disloyal citizens when he wrote that, “if the mainspring of popular government in peacetime is virtue, amid revolution it is at the same time [both] virtue and terror (la vertu et la terreur).” With the guillotining of more than 20,000 traitorous “enemies of the people,” Robespierre brought Rousseau’s draconian vision to life, establishing a precedent for apocalyptic revolutionary terror that has alternately inspired or terrified Westerners ever since.

The story of Robespierre’s rise to power and his spectacular downfall on the ninth day of the revolutionary month of Thermidor, Year II (27 July 1794), when he was guillotined along with 83 key collaborators, retains its dramatic appeal today. But in the history of Communism, Thermidor represents a dead end. The furthest Robespierre had been willing to go in socioeconomic reform was the “Law of the General Maximum,” passed by the National Convention in September 1793, which established price ceilings on grain, meat, oil, soap, salt, shoes, and other essentials; punishments for violators; and a cap on wages.

In the end, it may have been the national military draft, or levée en masse, of August 1793, not the short-lived Maximum of September, that established the more significant precedent for Communism. France’s government began forcibly conscripting soldiers and workers—from foundrymen and tanners and tailors to bakers—into the war industry, thus establishing a model for state direction and control of the economy, at least in wartime.

However radical their ideas seemed at the time, from the perspective of the modern socialist or Communist, Rousseau and Robespierre were not radical enough. Widely read in the West, Rousseau’s writings were never part of the Marxist-Leninist canon. For this reason, it is worth examining the work of one of Rousseau’s lesser-known contemporaries, who took his critique of social inequality further than Rousseau was willing to go.

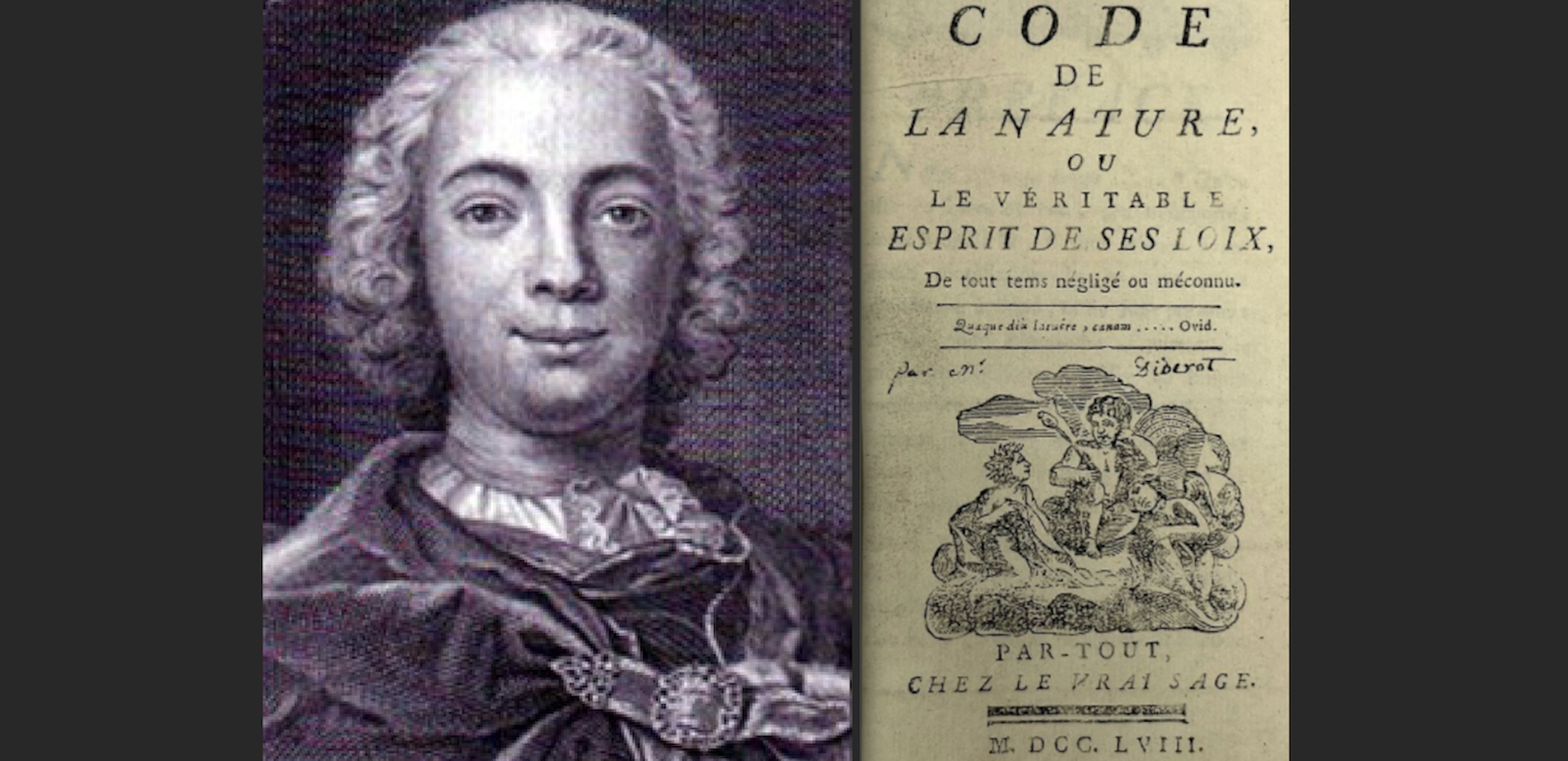

This was Étienne-Gabriel Morelly (1717–78), who, like Rousseau, started out as a tutor of modest means. Morelly, from the town of Vitry-le-François in northeastern France, published an anonymous pamphlet, Code de la nature ou le véritable esprit de ses lois (The Code of Nature or the True Spirit of Her Laws), in 1755, the same year that Rousseau published his Discourse on Inequality.

Morelly began his pamphlet in much the same vein that Rousseau began his own treatise, lamenting the fall of mankind into its present state of corruption, using the “noble savages” of the Americas as a rebuke to materialistic European civilisation, and attributing the bulk of human misery to social inequality. But Morelly, a truer (or at least more literal-minded) Christian than the Genevan autodidact, ascribed man’s descent to a single sin, a vice originating in the Garden of Eden itself: greed (avarice):

The sole vice that I can recognise in the universe is greed; all the others, whatever name we give them, are only tones, only degrees of [greed] itself, which is the Proteus, the Mercury, the base, the vehicle of all vices.

The “desire to possess,” he continued, was the “universal plague… of selfish interest” that tore at the social fabric. “Where no property exists,” Morelly prophesied, “none of its pernicious consequences will exist either.”

In Morelly’s view, it was not only the increasing prosperity and complexity of European society, compared to the material simplicity of life among “savages,” that had brought the evils of property and inequality to society, but also the corruption of Christianity. Once upon a time, Christians had been persecuted, and by this persecution had been “made to feel the equality of all men,” even slaves, whose suffering they had so nobly “softened.” Saints such as Martin of Tours had “recommended that the rich surrender their possessions and spread them in the bosom of the poor.” But this “spirit of charity” was destroyed by the greed of the Church, which erected “mediators between God and man” and siphoned off wealth from the poor to rich ministers of the faith.

To restore the true spirit of Christianity, and usher man into a modern utopia mimicking the humbler virtues of mankind’s lost Eden, Morelly proposed a series of laws “aligned with the intentions of Nature.” The first was that “nothing in society must belong to anyone, neither as personal possession nor as capital goods, except those things of which an individual makes immediate use for his need, his pleasure, or his work.” Second was that “every citizen must be a man of public sustenance, maintained and occupied at public expense.” Third, all citizens must “contribute on their part to the public utility according to their strengths, their talents, and their age.”

The key to his system, the “Economic and Distributive Law,” would stipulate that “all durable goods must be amassed in public storage facilities, whence they will be distributed, some daily and some for fixed terms to all citizens, in order to serve the ordinary needs of life, and the material requirements of the works of different professions; other goods will be furnished to people who use them.”

In order to prevent anyone from profiting from the variable distribution of goods, Morelly said further that “nothing can be sold or be exchanged between citizens.” The exchange of all goods must instead be regulated at “the public storage facility... where they will be supplied by those who cultivate them, and distributed only for fixed terms to those who collect them”—Morelly noted, in a nod to tradition, “to each family patriarch, for his use and that of his children.”

To discourage hoarding, those “fixed terms” must be short. “Someone who needs... greens, vegetables or fruits,” Morelly explained, “will go to the public square, which is where these items will have been brought by the man who cultivated them, and take what he needs for one day only.”

In a foreign-trade corollary, Morelly’s final law specified that, “if the state is aided by a neighbouring nation, or gives aid to the same, this exchange can only take place… in public, and one must take scrupulous care that it not introduce any private wealth into the republic.”

Here was a powerful vision of a propertyless commonwealth of radical social equality. It uncannily blended together the most promising post-pagan elements in the Western tradition, from Christian eschatology and early Christian notions of material renunciation and charity to Columbian romanticisation of the “noble savage” and post-1492 theorising about “utopia.” As French scholars have noted, Morelly cites (or channels) with equal enthusiasm Thomas More, Rousseau, and the philosophes.

His vision is somewhat crude and reductionist, jettisoning More’s curious tolerance in Utopia for slavery and enduring class and sex differences (with the exception of Morelly’s embrace of the paterfamilias), and subsuming the sceptical and tragic elements in Rousseau’s work inside the rationalist optimism of the philosophes. But Morelly is more honest, too, taking Rousseau’s premise about the “unnatural” evil of social inequality as the original sin of human civilisation to its logical policy conclusion: the forcible abolition of private property, sale, and trade and the monopoly of all economic activity by the state.

Small wonder Morelly’s work, though mostly ignored in his own lifetime, was embraced by early French socialists such as Charles Fourier, and later became a staple of the Marxist-Leninist canon under Soviet Communism.

Excerpted from To Overthrow the World: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Communism by Sean McMeekin. Copyright © 2024. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.