Art and Culture

A Joke Too Far?

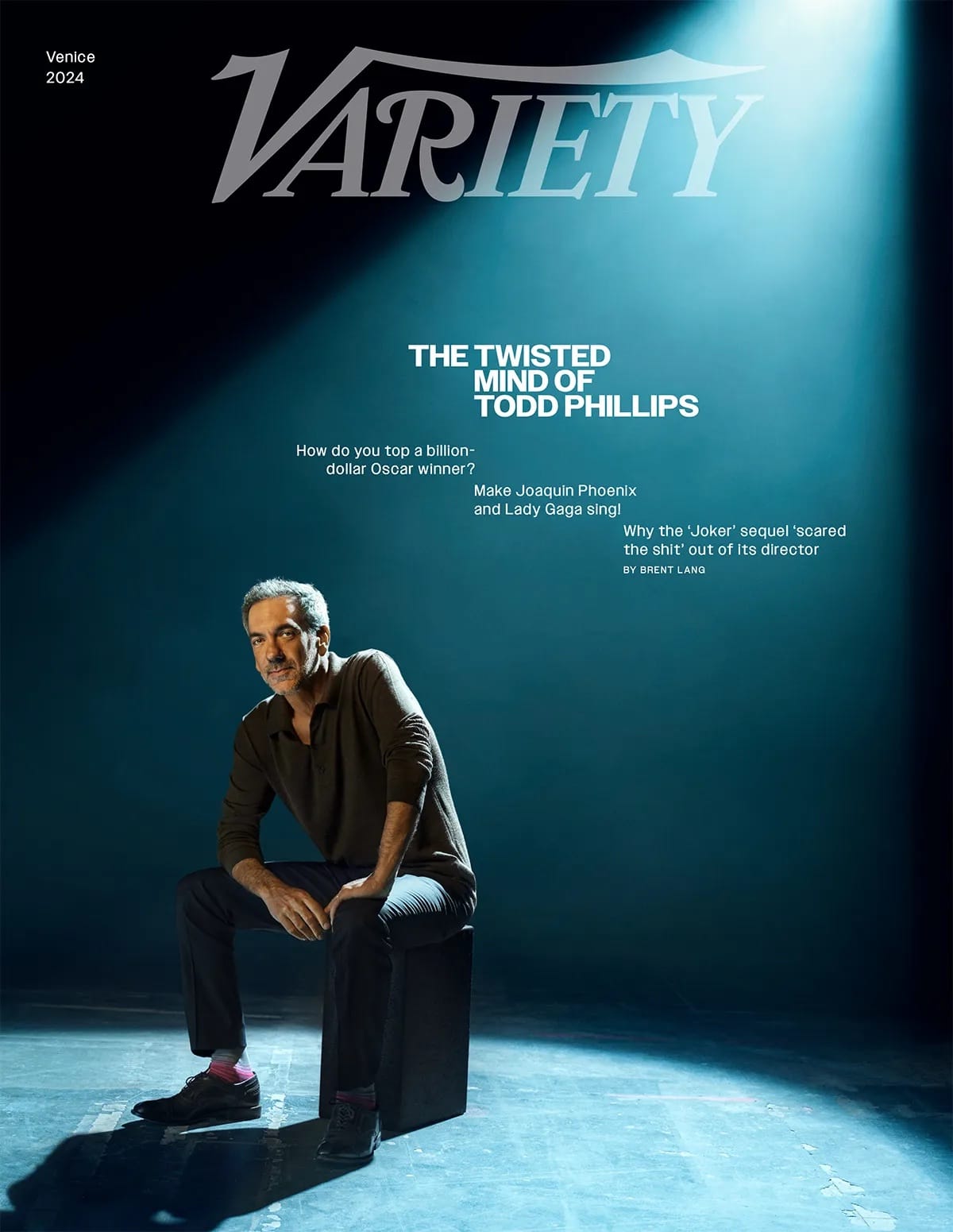

Todd Phillips’s unfairly reviled sequel raises interesting questions about the artistic licence auteurs take with well-known properties.

Note: The following essay contains spoilers.

On 22 December 1984, four teenagers, all of whom had previously been arrested, boarded a New York subway train with the intention of robbing a downtown arcade. Two of them cornered a mild-mannered loner named Bernie Goetz and demanded five dollars. They did not know that two previous muggings had left Goetz with a permanently damaged knee, and that he’d taken to carrying an unlicensed gun for self-defence. He fired five times, wounding all four and leaving one permanently disabled, before escaping into the subway tunnel.

I was living in Hell’s Kitchen (now fashionable “Clinton”) at the time, and I can attest that the city celebrated “the subway vigilante” as a hero. Back then, New York was averaging two thousand murders a year, and an average of 38 crimes were being committed every day on the graffiti-encrusted urinal that passed for our subway system. Some saw a racial panic narrative—Goetz was white and the teens were black—but Goetz enjoyed equally strong support within the black community. (A backlash followed when it was revealed that Goetz shot two of the teens in the back and said, “You don’t look so bad. Have another,” before taking a final shot at a third.)

Director and co-screenwriter Todd Phillips included a fictionalised version of the Goetz shooting in Joker (2019), his 1980s origin story for Batman’s chief nemesis. The Goetz case also informed Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns (1986), the seminal graphic novel that cemented Batman’s return to his dark roots. That same vigilante spirit produced New York’s Guardian Angels and the election of the city’s law-and-order mayor Rudolph Guiliani. Today’s social breakdown, propelled by the Right’s MAGA conspiracy theories and the Left’s Orwellian attacks on language, has created vigilante militia movements and social-justice mobbing.

It is hardly surprising, then, that Phillips’s reinvention of the Joker as an accidental vigilante rather than a criminal mastermind hit the zeitgeist. Joker won the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival, scored eleven Oscar nominations and two wins (for sound and best actor), and became the first R-rated picture with a billion-dollar box office. Alas, the sequel, Joker: Folie à Deux, has been a historic failure, boasting the worst CinemaScore and the biggest second-weekend box-office drop for a comic-book movie in history. It may yet lose US$200 million.

This is a pity, because despite a few plot holes, Folie à Deux is a smart, gutsy swing for the fences. Its reception almost certainly has more to do with fans’ expectations than what’s actually onscreen, which raises interesting questions about the artistic licence auteurs take with well-known properties, the relationship between artist and audience, and the role social media plays in generating controversy and commercial success.

The Joker made his first appearance in 1941 during the Golden Age of Comics. Jerry Robinson’s concept sketch reminded writer Bill Finger of Conrad Veidt in The Man Who Laughs. This led Finger and Batman creator Bob Kane to develop the story of a sadistic jewel thief and serial killer who murders his victims with a toxin that leaves them with a rictus grin. (Robinson, Finger, and Kane each tell a different creation tale.) The supervillain was supposed to die in his first outing but was rescued by editor Whitney Ellsworth, who correctly identified his potential. He proved so popular that he went on to appear in nine of Batman’s first twelve issues, thereby cementing his status as the Dark Knight’s arch-nemesis.

For eleven years, the Joker’s backstory remained a mystery. But since 1951, most versions of his biography have been variations on The Man Behind the Red Hood (Detective Comics #168). The Joker was either a master criminal, a petty thief, a hit man, a lab assistant, or a failed stand-up comic who tried to rob Ace Chemicals or the Monarch Playing Card Company, either to steal a fortune for himself or to get money for his pregnant wife. He was foiled during the heist by Batman and fell into a vat of chemicals or escaped by diving down a drain of chemical waste or had chemicals dumped on him. The chemicals bleached his face white, turned his hair green and his lips bright red, and drove him insane.

But the Joker has also been a child subjected to a chemical gas attack by mobsters who broke his jaw; an unkillable, eternal creature, possibly the devil; a set of twins; and a baby scrubbed with bleach by his abusive Aunt Eunice. Chemical scarring is optional. The Jokers played by Cesar Romero (in the camp 1960s TV series) and Heath Ledger (in the second part of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy) were both shown without makeup, unblemished. Ledger’s character was disfigured by a Glasgow grin, which was either self-inflicted or carved into his face by an alcoholic father screaming, “Why so serious?” Both accounts may be false—maniacs make unreliable narrators.

DC, the comic-book company that owns the rights to the Batman universe, had good reasons to fudge the Joker’s past. Mystery is, after all, central to his mystique. That may be why the Joker is the only villain without a backstory in the Emmy Award winning Batman: The Animated Series (1992–95). He didn’t even have a name until Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) identified him as Jack Napier, a name derived from “jackanapes” (or possibly a reference to star Jack Nicholson and Alan Napier, who played Alfred the butler in the Batman TV series). As the Joker says in the DC classic The Killing Joke (1988): “If I’m going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice.”

Burton’s movie was also the first time the Joker was fingered for killing Bruce Wayne’s parents. In Batman’s 1939 origin story, Detective Comics #33, they were slain by an anonymous mugger, later revealed to be hoodlum Joseph Chilton, aka Joe Chill. Other adaptations have pinned the blame on Matches Malone and Carmine Falcone.

Creators can enjoy a generous amount of artistic licence with popular, fictional characters: Sherlock Holmes can be reimagined as a contemporary New Yorker with a female Asian Watson; Robin Hood can be a Thirties bootlegger or a figure of farce; and Dracula can meet Abbott and Costello. But any re-invention must retain the character’s salient characteristic— respectively, as the world’s greatest detective, a thief who steals from the rich to give to the poor, or a vampire count.

The Joker is a chaos-agent and comedian. (He is also almost always paired with Batman. The 1975 Joker comic-book series without the Caped Crusader lasted only nine issues.) Cesar Romero played him as a mischievous clown; Jack Nicholson, as a hammy but sadistic crime boss; Mark Hamill (in the animated series), as a dark and giddy grotesque; and Heath Ledger, as a nihilist with a pitch-black wit. Phillips’s Joker, as played by Joaquin Phoenix, offers his own unique take on the Joker archetype.

Echoing The Killing Joke, Arthur Fleck is a professional clown-for-hire and would-be stand-up comedian in Gotham, New York. He is afflicted with a disturbing Tourette’s laugh and takes medication for severe trauma, a result of childhood physical and sexual abuse by a former boyfriend of his emotionally demanding and mentally ill mother, for whom he cares between her stints at Arkham State Hospital. Mocked at work, Fleck is given a gun for protection after he suffers a beating at the hands of a group of street kids, but he loses his job when it falls out of his clown costume at a children’s hospital. Still in makeup on the subway home, he’s assaulted by a group of rich (white) Wall Street bros who work for the father of young Bruce Wayne. He snaps, kills them, and escapes. Alienated crowds don clown masks in support.

Meanwhile, budget cuts leave Fleck without support or medication, and he spirals after a series of psychological blows—he realises that an imagined romance doesn’t exist, he discovers that he isn’t Bruce Wayne’s half-brother (a fiction concocted by his mother), and late-night host Murray Franklin airs a viral video of his disastrous one-and-only club performance and calls him a “joker.” Fleck smothers his mother and stabs an ex-colleague before appearing as a guest on Franklin’s show, billed as Joker. In the stunning climax, he admits he’s the subway vigilante, delivers a speech about the collapse of the social safety net, and with a joke, shoots Franklin in the head. Riots erupt, during the course of which, a thug in a joker mask murders Bruce Wayne’s parents.

Critics were divided. Some reviewers favourably compared Joker to Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and The King of Comedy (1982). Others incited a social panic, describing Joker as an “incel-friendly,” “toxic,” and “dangerous manifesto for radical and lonely white men” that might inspire copycat violence with its “irresponsible propaganda.” SWAT vans were in attendance when Phillips and Phoenix walked the New York Film Festival red carpet. Officials at a US Army base in Oklahoma warned of a “credible potential mass shooting” at an unknown theatre based on “disturbing and very specific chatter on the dark web.” The NYPD stationed officers at all New York screenings. No incidents were ever reported.

That most of the anxiety about Joker’s alleged social irresponsibility came from left-leaning publications is indicative of progressive hypocrisy on incels. Incels are never described as a “marginalised community” or as “persons experiencing involuntary celibacy.” Nor do they have advocates who insist on a compassionate examination of “the root causes” of their pathologies. Arthur Fleck is a product of childhood trauma who explodes when he is denied treatment. Far from fascist art, Joker is more obviously read as a leftist defence of the excluded that calls on the government to provide better resources for treating mental-health problems and supporting sufferers.

Joker is a revenge drama. But while the vigilante antiheroes played by Clint Eastwood or Charles Bronson (or Batman himself) are righteous avengers of injustice, Fleck’s Joker is a loose cannon whose behaviour is entirely spontaneous and reactive. Even Murray Franklin’s killing is an impulsive act that derails Fleck’s plan to commit suicide live on TV. This lack of agency left some Joker viewers cold. But like many others, I was mesmerised by the brutal theatricality of Phillips’s vision, Lawrence Sher’s grim cinematography, the vivid supporting cast (including Robert De Niro as Murray Franklin and Frances Conroy as Arthur’s mother), and the raw performance by Phoenix.

Joker was intended as a standalone film, and its narrative arc appeared to answer all the questions about the character’s origins as an iconic villain. But then Phoenix told Phillips about a dream he’d had in which Joker was on stage singing songs. This led the pair to imagine a musical fantasy in which their inarticulate creation could express his feelings through standards. This would also allow them to introduce a romance between Joker and his DC squeeze and partner-in-chaos Harley Quinn (who appears in the sequel under her pre-criminal name Harleen “Lee” Quinzel).

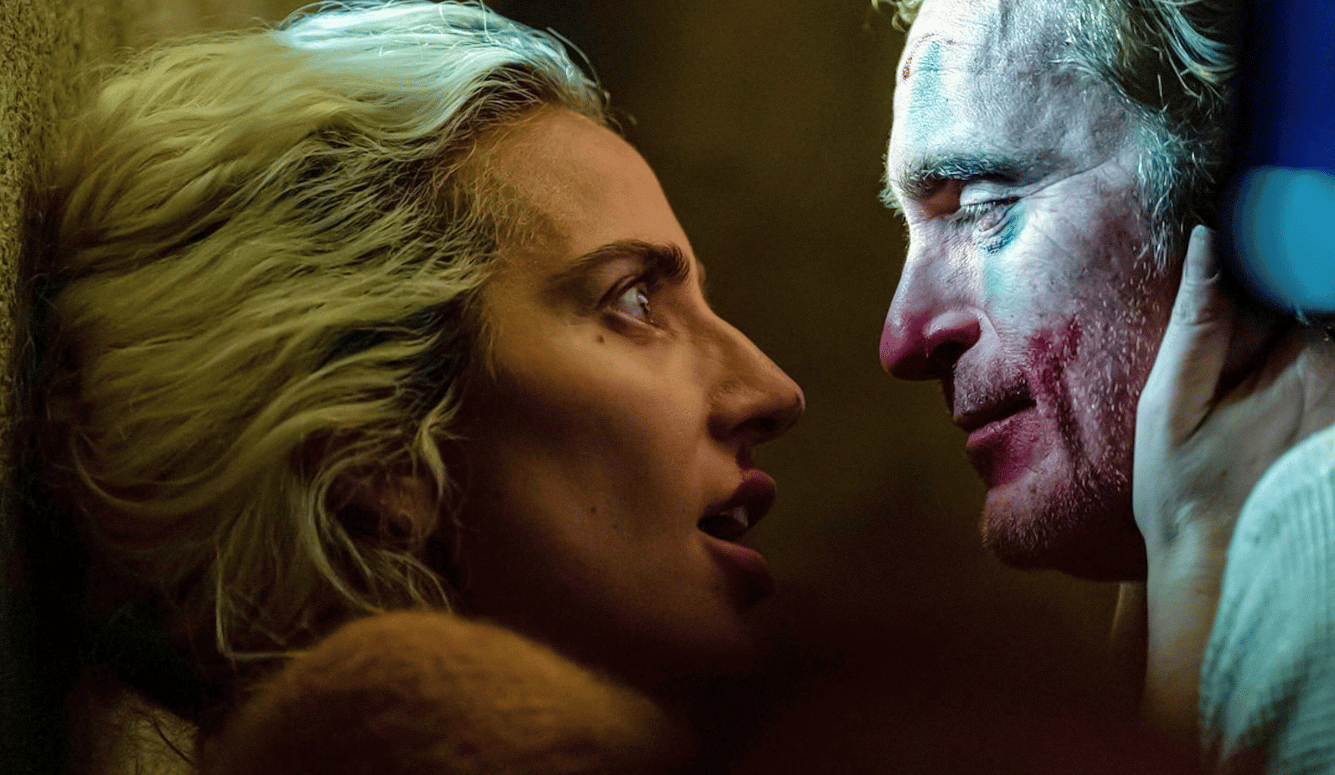

Bold and original, the concept expands upon Joker’s narrative and stylistic possibilities and picks up from the first film’s final scene, in which Arthur Fleck is seen killing, singing, and dancing through Arkham to Frank Sinatra’s “That’s Life.” Folie à Deux executes its premise perfectly. A medicated Fleck meets Quinn (a magnificent turn by Lady Gaga) at Arkham’s minimum-security choir club. After a short sing-along, snatches of music on one of the institution’s TVs lead to half-spoken lyrical conversations, and soon the two characters are performing production numbers that only exist in Fleck’s head. It’s a musical, yes, but an unconventional one, in the spirit of Herbert Ross’s 1981 film Pennies from Heaven.

Lee Quinn is an adult child of privilege—a manipulative narcissist who can book herself in and out of psychiatric hospitals, returning at will to her family’s home on the Upper East Side. Repelled by sad sacks like Arthur Fleck, her affair with the infamous Joker gives her status as she imagines herself as a revolutionary nihilist. She is, in short, a white, bourgeois, Antifa phoney.

This reconception of Harley Quinn could have taken Folie à Deux in new directions that remained true to DC’s world. For instance, Fleck and Quinn might have broken out of Arkham and begun a Gotham City crime spree, fuelled by Quinn’s wealth and her family’s social connections. She could have become a Karla Homolka—an excited participant in Joker’s crimes—or a version of Patty Hearst, a wealthy heiress either seduced by Joker’s mystique or a victim of Stockholm Syndrome.

But Phillips and Phoenix had other ideas, which have nothing to do with DC, and they seem to have enjoyed subverting and confounding their target audience’s expectations at every turn. “We didn’t want to have [Fleck] as the clown prince of crime or running a syndicate of criminals,” Phillips told Variety for its pre-opening cover story. In an interview with Empire, he added: “Arthur clearly is not a criminal mastermind. He was never that. … Arthur has become this symbol to people. This unwilling, unwitting symbol now paying for the crimes of the first film, but at the same time finding the only thing he ever wanted, which was love.”

This novel approach may have excited Phillips’s and Phoenix’s sense of artistic possibility, but it violated an unspoken contract between audience and artist. An audience will suspend its disbelief so long as the artist doesn’t change the rules in the middle of the game. Joker told what fans believed was an origin story of a character they had grown to love. And having laid the psychological groundwork, they naturally expected the sequel to explore his subsequent life of crime. A rom-noir works as a sequel about Arthur Fleck, but not about the Joker, who was the reason the public forked out a billion bucks and made a multimillion-dollar sequel possible. As Rolling Stone put it: “Folie à Deux Has a Message for Fans: Go F-ck Yourselves.”

After Fleck and Quinn’s Arkham breakout is foiled, the rest of the movie develops their relationship as Arthur prepares to face trial for the murders he committed in Joker. The film reaches its climax when Fleck confesses in court that he’s responsible for the killings and explains that Joker was a disguise he created when love seemed impossible. Quinn feels betrayed and storms out of the court, much as the audience stormed out of Phillips’s sequel. The film ends with Fleck being stabbed by a fellow Arkham inmate as he goes to meet an unidentified visitor. This Joker will never meet Batman. But as he bleeds out on the floor, his killer uses the shiv to carve himself a Glasgow grin.

It is no wonder that DC fans felt betrayed, and as mentioned, the script does have its problems. It doesn’t really make sense that Lee can discharge herself after she starts a fire at Arkham and tries to help a dangerous inmate escape. It is unlikely that the guards would beat Fleck given publicity around his trial. And Fleck’s confession before the jury is not especially plausible, given that he destroys any chance of freedom and a life with Lee. Nevertheless, I didn’t share the hostility of the critical and popular consensus. On the contrary, I found myself transfixed by the power of Phillips’s imagination, the dazzling theatricality of the musical numbers, and the electrical chemistry between Phoenix and Gaga.

Arthur Fleck may not be the Joker of DC lore, but Phillips hints that his chaos may have created the true Joker—the masked thug who murders Bruce Wayne’s parents in the first film, or perhaps Fleck’s own assailant at the end of the sequel who cackles as he self-mutilates. There’s a more frightening possibility—that Arthur Fleck’s nihilism has created so many other jokers that order in Gotham will never be restored.

Folie à Deux has received a critical acid bath, but it is already developing a cult following among contrarian filmgoers and critics. Revisionist adaptations of The Long Goodbye and Pennies from Heaven were also misunderstood upon their initial release and only later embraced as modern classics. I am confident that, in time, Todd Phillips’s creatively ambitious but flawed film will benefit from a similar reassessment. At which point, it will finally find the audience for which it was intended.

CORRECTION: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article referred to Dennis Potter’s TV series Pennies From Heaven when the author’s intended reference was the 1981 movie. Apologies for the mistake.