Education

Preparations, Not Reparations

If good educational opportunities were there for the taking, the sense of racial injustice in America would be much less.

A debate is sweeping the United States, as to what, if anything, America owes to the descendants of enslaved people. It’s a question that strikes at the heart of the American project. Dismissing it will not make it go away. Nor will throwing inordinate amounts of money at it. The question of reparations isn’t a debate to be won. It's a wound to be healed. But there is a way to heal it that most Americans would probably support: The US should invest far more in early education.

In 1864, just before the end of the American Civil War, General William T. Sherman, commander of the US Army’s Military Division of the Mississippi, granted forty acres of land each to approximately 18,000 formerly enslaved families under his Special Field Order No. 15, issued with the approval of President Lincoln. The order was meant to ensure “harmony of action in the area of operations.” It enabled Sherman to provide for the thousands of black refugees who’d been following his army since its invasion of Georgia, and whom he could not afford to support or protect while on campaign. In a later order, Sherman authorized the army to loan mules to the newly settled families. Granting land to freed slaves made sense. It gave them a chance to provide for their families and invest in their futures. It set the stage for true and lasting equality with whites to emerge. But Special Field Order No. 15 was short-lived. In late 1865, less than a year after it was issued, and after many black families had already been resettled, President Andrew Johnson reneged on the order, returning the 40-acre parcels to their original owners, who declared loyalty to the Union.

To contemporary advocates of reparations, the story demonstrates America's failure to make good on its promises to African Americans—both in the years immediately following the Civil War and during the Jim Crow era and beyond. Had policies along the lines of Special Field Order No. 15 been implemented throughout the land, along with genuinely equal treatment, advocates argue that racial disparities would be virtually non-existent in America today. Today’s government, they argue, should act in a similar fashion, by providing cash payments to the descendants of slaves in order to close the wealth gap between them and whites, as is currently under consideration in the state of California. But Special Field Order No. 15 did not grant freed slaves equal wealth with whites. It granted them the opportunity to work the land and accumulate wealth through their own efforts. It encouraged self-reliance.

The single best way to provide a similar opportunity today is to give everyone access to high-quality early education.

Early educational deficits are, of course, not the only reason blacks lag behind whites in income and wealth. Racial discrimination also plays a role. So do differences in healthcare and childhood nutrition. But providing good universal early education is the most effective thing that government can easily do.

Contemporary reparations proposals typically include monetary payments. In California, for example, a 2023 task force recommended the state pay $300 billion in reparations: 2.5 times the state’s annual budget. Inflationary concerns aside, the problem is not that such programmes are expensive. It’s that they are unfeasible. From a practical standpoint, the first question is, who should receive reparations? How much African American ancestry must a person possess to claim eligibility? In their influential book, From Here to Equality, William A. Darity and Kirsten Mullen recommend that “individuals must demonstrate that they have at least one ancestor who was enslaved in the United States” and “demonstrate on a legal document that they have self-identified as black” for “at least twelve years.”

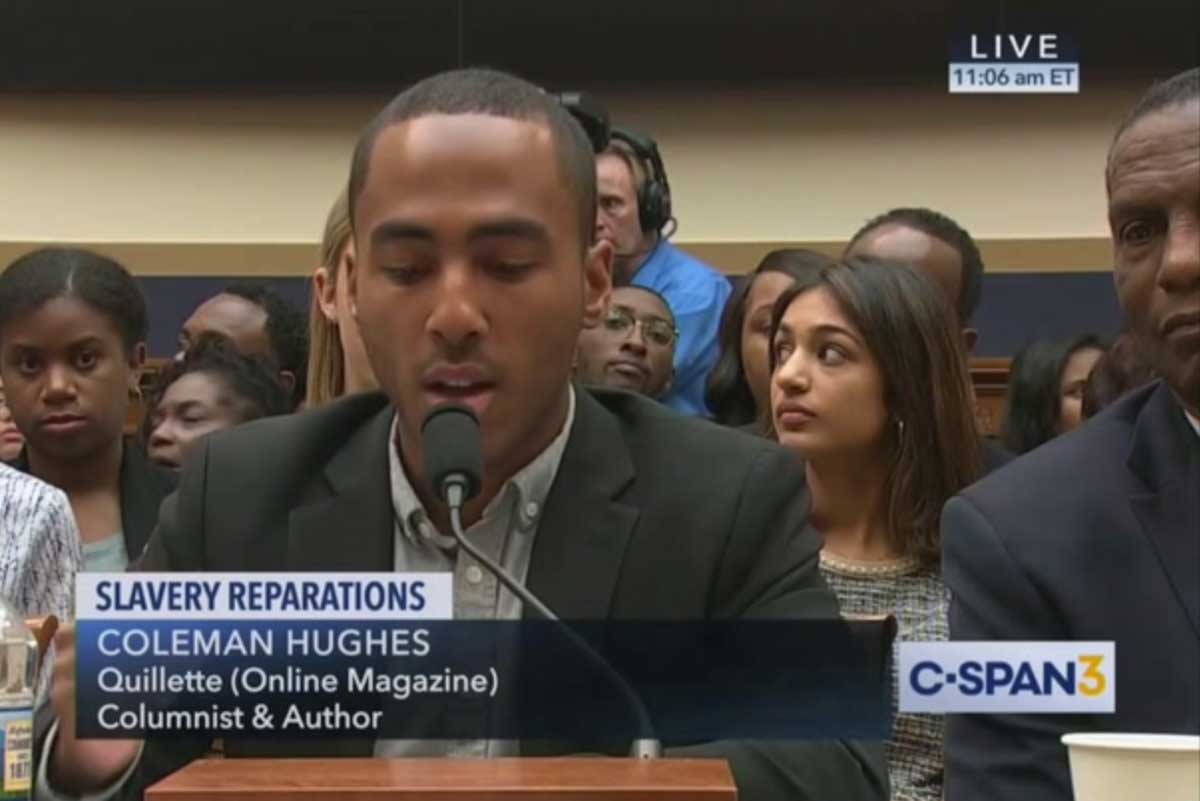

But what about people who identify as black but are unable to prove their slave lineage? What about people who can prove their lineage but choose to identify as something other than black or as more than one thing? What about people who meet both criteria but who do not think contemporary blacks deserve reparations or who would feel stigmatized or demeaned by reparations? Coleman Hughes is among the latter group. In his 2019 testimony to Congress, he commented:

the moment you give me reparations, you’ve made me into a victim without my consent. Not just that, you’ve made one-third of black Americans who poll against reparations into victims without their consent. And black Americans have fought too long for the right to define themselves to be spoken for in such a condescending manner.

And what about the many African Americans who are already wealthy?

Even if we could decide who should get reparations, how do we decide who should pay? Should we impose this tax only on descendants of slave owners and on businesses that profited from slavery or on all white people—even recent immigrants whose ancestors had nothing to do with slavery or Jim Crow?

Is it fair to force people today, who never owned slaves, to compensate people today, who never were slaves, just because they both live in a country where slavery was once legal? If so, where should we draw the line? What about the descendants of Native Americans, or nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants, or Jews, the Irish, women, homosexuals, etc.? Should they also receive reparations, or at least not have to pay them?

And how much should be paid? Should the amount be merely symbolic, a gesture of apology to complement the apologies that have already been issued by 13 US states and the US House of Representatives? Should the amount be the same for everyone or should it be prorated based on the amount of African American ancestry one can claim? Should the amount be calibrated to eliminate the current black–white wealth gap? If so, what happens if over time the wealth gap reopens? These practical and ethical dilemmas may help explain why, in a recent Gallup survey, two-thirds of Americans and one-fourth of African Americans opposed reparations.

Instead of attempting to eliminate the US black-white wealth gap overnight using cash payments, which experts estimate would cost a staggering $14 trillion, we recommend investing government resources in education, especially early education. Because such investments would be aimed at preparing African Americans to compete and succeed, we might think of them as providing “preparations” instead of reparations.

In 2014, economist Roland Fryer and his team conducted a fascinating randomized experiment at 16 inner-city Houston state schools. They fired the principals and about half the teachers at those schools, replacing them with better candidates, made the school day longer, gave students extra tutoring, and set additional exams. Perhaps most importantly, they promoted a culture of high expectations. Within a short time, Fryer’s interventions produced a 0.103 standard deviation increase in math scores for black kids, with even larger gains for Hispanic kids, elementary-aged kids, and kids from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. It’s not clear whether this will lead to greater success in adulthood for these children, of course, but this seems promising.

Fryer’s approach differs considerably from some recent efforts to promote equity by lowering academic standards. The city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, for instance, removed algebra and all advanced math from its junior high schools. The new California Math Framework likewise recommends delaying teaching algebra until high school. These measures are meant to reduce racial disparities but are likely to backfire. Wealthy families will simply pay for math tutors or enroll their children in private schools, while children from less wealthy families who happen to have a strong aptitude for math will miss out on early math education.

Fryer’s approach is a much better model. It’s consistent with the principles of equal treatment and equal opportunity and its success can be seen in the academic performance of the children themselves: an objective metric. It should also appeal to both liberals and conservatives—to liberals because it focuses on raising the quality of education in the poorest performing school systems, and to conservatives because it would do so in a race-neutral way.

Of course, investing in early education does not guarantee equal outcomes across groups, or what today's racial justice activists call equity. But the government does have an obligation to make sure that good educational opportunities are there for the taking. If they were, the sense of racial injustice in America would be much less.