Politics

Will Britain Get a New Right Party?

If the Conservative Party slumps to defeat in next year’s election, Britain could see the rise of a populist alternative.

In 1932, a charismatic aristocrat named Sir Oswald Mosley founded the British Union of Fascists, an organisation that strove to popularise the ideas and strategies of Italian Fascism and German Nazism, including the hatred of Jews, Roma, homosexuals, and the disabled. Within a few years, it had recruited some 40–50,000 members. Mosley and most of the BUF’s membership (including Mosley’s wife) were interned by the British government in 1940, and the organisation was banned. In 1943, Mosley was released from jail and placed under house arrest. After the war, he continued to spread fascist and racist ideas, and died in France in 1980, his life a failure.

By the time the war ended in 1945, Britain was broke, but its international reputation had been enhanced by a longer struggle with Nazism than its allies. Consequently, a far-Right party of any size was never able to become a viable project. Small far-Right, fascist-inclined groups emerged to target immigrants, but any success they enjoyed was local and short-lived, and the Conservative administration of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1979–90) left no space for a radical right-wing tendency.

The past seven years, however, have been torrid in many countries, not least in the UK. Britain has left the European Union, the malign effects of the COVID pandemic continue, and social and economic strife have provided a backdrop to the rise of far-Right parties in a number of continental nations. Britain’s ruling Conservative Party has cycled through four leaders in that time (Liz Truss managed only 44 days in office, making her the shortest-serving PM in British history) and now appears to be doomed to a savage defeat when an election is held next year. The party is at war with itself, unable to halt illegal immigration, and presides over some of the highest inflation in Europe.

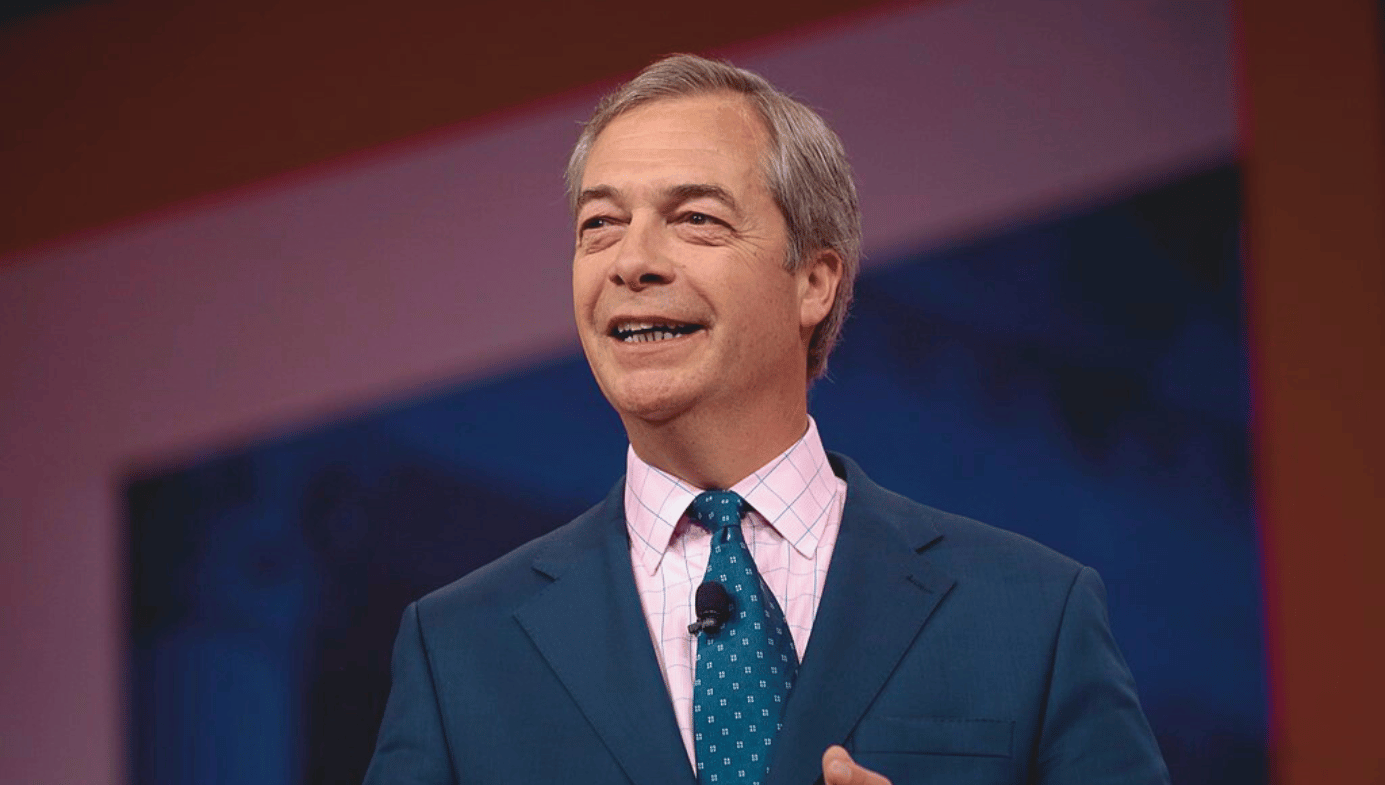

Ordinarily, when a governing party finds itself in this kind of trouble, the preferred solution is to call for a new leadership to reset direction. Having lost patience with this kind of deckchair-rearranging exercise, rightwing activists and populist commentators are responding to the present Tory crisis by calling for a new party instead. The most influential voice in this audacious project is that of Nigel Farage. He proved his political entrepreneurialism by founding the single-issue Brexit Party—a success that established him as one of a small group of instantly recognisable politicians. Though the Reform Party he created out of Brexit has yet to take off, the public fight between Farage and Coutts elite bank earlier this year—which Farage won decisively—provided a reminder of his ability to dominate the media and of his gifts as a populist bruiser.

Farage succeeded in turning his row with a powerful institution into a national, popular issue—it emerged that other customers, who lacked the public platform Farage enjoyed from which to retaliate, had suffered the same fate he had. Even some of his opponents admitted that the episode revealed an ability to lead and represent people who feel mistreated by the establishment. For the past two years, Farage has hinted that he would be interested in creating a new party, ideally with former Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who is now without a seat in parliament. Johnson is wary of Farage, but the temptation to recover the support and admiration he covets, and to take revenge on those in the Conservative Party who forced him out, may prove too great to resist.

In the first weeks of August, two voices—with political heft and a wide readership, respectively—have come out strongly for a new party. One of these belongs to Dominic Cummings, an expellee from Johnson’s government, where he was a high profile political adviser. Cummings is considered by many (not least by himself) to have been the brains behind the Brexit vote, and since he was ordered out of Downing Street in November 2020, he has tended a waspish Substack column and Twitter feed. In October last year, he tweeted that several special advisers were sending him inquiries about a possible job in a new start-up party.

Lots of spads texting Vote Leave 'can we get a job in your new startup party when we collapse?'

— Dominic Cummings (@Dominic2306) October 13, 2022

Some of you yes, those of you attacking science funding you will be hung from no10 lamposts...https://t.co/z8OHS9LaCs

In the Critic, Henry Oliver has written that Cummings “is precisely the right person to run such a party. … He understands that voters are both right and left wing, holding a mingle of opinions rather than conforming to ideological ideas. He is a campaign innovator, and he has a strong sense that something is rotten in the state and needs to be changed.” In the succeeding months, Cummings appeared to brood over whether or not he was the right person for this job. Then, in the first week of August, he finally floated the idea in an article replete with his customary contempt for the political class. Within the denunciations, however, was a clear intent, boldly announced in the headline over his lengthy post (albeit one qualified by a question mark): “The Startup Party: Time to Build from September and Replace the Tories?”

Cummings believes that Prime Minister Rishi Sunak possesses “the highest IQ in parliament and the toughest work ethic,” but that he is not an authoritative political leader, has “no grip on power,” and behaves like “a good head boy” without “political strategy worth spit.” The result of this combination, he predicts, is inevitable “political disintegration.” Sunak, Cummings maintains, has no time to learn to become an effective leader, so the Tories will duly surrender power next year to the “dud” Labour Party leader Sir Keir Starmer, who “will fail from day one.” Starmer, meanwhile, is pursuing a risk-averse centrist strategy, distancing his party from any policy which might be perceived as radical. The space between the Conservative government and the Labour opposition seems to shrink with every new announcement.

Having disposed of both His Majesty’s government and the opposition in his post, Cummings turned to what he has been nourishing in his mind since his ejection from No 10 (and perhaps before):

This is the time to start building the replacement so that from 2200 on election night in October-December 2024 the old Party is buried and a new set of people with new ideas start talking to the country and can take over in 2028 and give voters the sort of government they want and deserve. [His emphasis]

Why should the thoughts of one person—a talented one, but one who no longer exerts any influence in government—be seen as important? Partly because Cummings retains respect, albeit without affection, for his organising and tactical abilities. At least as important, the political space into which he drops his ideas is now febrile and disjointed—the governing party’s restive membership is facing a large increase in membership fees, Sunak lacks solid support, and Cummings intuits that there is meaningful appetite for change to be exploited.

Cummings received instant endorsement from Matthew Goodwin, a professor of politics who has lately exchanged analysis for advocacy, and whose daily Substack columns betray his growing impatience with the “echo chamber” of the political class and the monoculture of the academy. “With the ratio of left-wing academics to right-wing academics now nine to one ... few people in the Ivory Towers are saying anything remotely interesting.” Goodwin evidently harbours an ambition to play a significant role in developing a new form of politics. In his reply to Cummings, Goodwin elaborated on Cummings’s claim that the country now demands deep political and social transformation:

The two big parties have failed for decades. They are no longer able to satisfy the very large majority of voters out there who are crying out for the kind of radical change the two Dinosaur Parties are unable and unwilling to deliver—largely because of path dependency (they were built for a different era) and also inertia (the dominant factions of Left and Right, as well as the media, are filled with the same kinds of people, who have the same backgrounds, who go to the same parties, and share the same reluctance to rock the boat because they all have an interest in keeping this sinking Titanic afloat[)].

Goodwin doesn’t much like Cummings, who loosed some venom on him during the Brexit campaign because the academic had the audacity to disagree with the political adviser on tactics. But he has found that they tread the same path, more or less. Cummings believes that mathematicians and physicists should replace graduates in politics and history as counsellors to government ministers, an idea that Goodwin deems overly technocratic. Goodwin’s instincts are populist—he believes the new party will need a “cluster of issues” that will galvanise political debate. These include:

- A “much tougher approach” to crime, which most believe is now “out of control.”

- A promise to do “WHATEVER IS NECESSARY” to stop illegal immigration and cut legal immigration: “70 per cent of voters OUT THERE IN THE COUNTRY will back you.” [His capitals]

- A commitment to strongly oppose “woke political correctness” because everyone hates it.

- Developing a “much stronger and more unified STORY about who we are and what holds our increasingly diverse and now unravelling society together. And that story, about our HOME, is the only one capable of uniting an increasingly fragmented and divided population.”

- The promotion of economic populism, which would mean war on elite tax evasion in tax shelters, “obscene” executive pay, and the battering of the working class by “hyper-globalisation.”

Private spats and divergent approaches aside, Goodwin, Cummings, and Farage agree on this much: governments of the centre-Right and centre-Left have run out of ideas and lost a stable mass base. They all believe that the answer lies in a populist politics, and that the prevailing liberal elite must be superseded by administrations that look to the people for legitimacy and authority, and not to institutions, senior civil servants, NGOs, and academics.

Were they to pull it off, such a project would resemble the New Right parties now rising in European states. That would damn it in the eyes of most politicians and commentators, but the specifics will be more important than the generalities. It is increasingly evident that, while continental populists hold similar views on the EU, globalisation, the family, and the nation, they differ importantly in their adoption of policies and rhetoric. This difference is between those parties that claim to be wholly democratic and fully cognisant of the rule of law, and those comfortable flirting with fascist and Nazi tropes.

Those with postwar roots in far-Right movements—such as the Sweden Democrats, the Italian Fratelli d’Italia, the French Rassemblement National—appear to have done much to ensure that a reversion to extremism on the part of members will meet with rapid expulsion. Over the past three years, the Labour Party, which no-one can sensibly view as extremist under its present leader, has expelled members who have shown a tendency to antisemitism. Others—such as the German Alternativ für Deutschland and the Romanian Alliance for the Union of Romanians—have in their ranks, and often in their leaderships, individuals who appear to see in the fascist and Nazi movements at least some inspiration.

A British New Right party will have no roots to disown (no-one would claim links to Mosley’s British Union of Fascists). And in an increasingly multiethnic country, routinely seen as among the countries most welcoming to immigrants, it would make no sense to adopt policies that even hinted at racism. A new party would stand or fall on the central assumptions of its would-be creators—that there is a potential mass following of those who feel marginalised and disrespected by elites; that these people wish to have their contribution to the nation recognised, not least by decent wages; and that they wish to have their input welcomed, heard, and respected in local, regional, and national politics.

To construct such a government is a challenge with which the Fratelli d’Italia and the Sweden Democrats are now wrestling. So far, there is little indication that they are tempted by extremism. Yet only by long engagement with the realities of government can the proof of their attachment to democracy, to human and civil rights, and to the rule of law be judged.