Politics

Woke Capitalism Gets a Black Eye

The dictatorial possibility tucked inside the commitment to “inclusivity” has rebounded, satisfyingly, on the perpetrators.

A lot of contemporary news is dire, and only in part because journalists believe bad news to be a more honest form of journalism. Much that is happening in the world is dire. So, it was a matter of some joy that, in the UK these past two weeks, the forces of ultra-progressivism suffered a rare—and possibly consequential—public defeat.

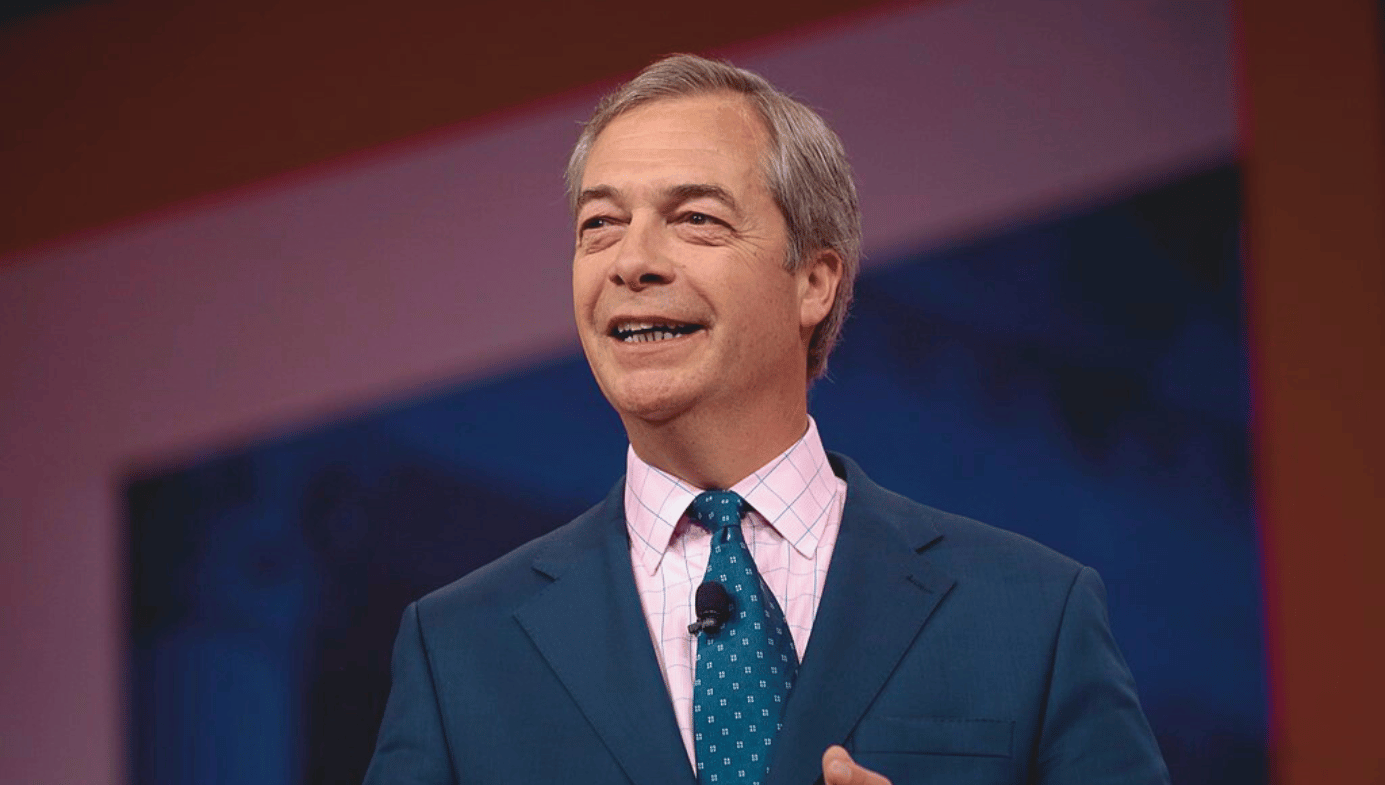

It is all the more joyous that this happened at the very top of the British establishment. A new establishment had grown in the womb of the old, and it is now spoiling for a fight. But by targeting Nigel Farage—the most talented populist the UK has produced in recent years, outdoing even the Scottish National Party’s Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon—those who sought to humble him set him up as a tribune of the people, fighting on behalf of those who had penalised for unfashionable views. Farage is presently enjoying himself mightily, as well he might, demanding that heads roll, as two highly placed heads already have.

The story is this: Nigel Farage, former leader of the UK Independence Party and the main architect of the vote for Brexit in 2016, banked with Coutts, a prestige outfit with a large office on London’s Strand. Coutts is one of the oldest banks in the world, and boasts of serving elite customers since the reign of Queen Anne (1702–14). It is a “private” bank, the name given to banks which deal exclusively with customers of “high net worth,” and it provides a range of services tailored to the needs of millionaires and billionaires. Its clientele is global, and customers must have at least £3m in their accounts, though a large part of that clientele would regard that as an afternoon’s shopping at Harrods. Its reputation for confidentiality and efficient wealth and portfolio management has been largely unquestioned.

Earlier this month, the BBC’s Business Editor Simon Jack reported that Farage’s account at the bank had been closed because he lacked the financial recourses required to keep it open. The story was greeted with waves of schadenfreude from Farage’s many political opponents and those who voted to remaining in the EU. But it was almost immediately shown to be untrue. Jack had been briefed that Farage did not meet Coutts’ financial requirements by Dame Alison Rose, the CEO of NatWest bank, the partly state-owned banking group which owns Coutts.

Furious, Farage had filed a Subject Action Request, which compelled disclosure by Coutts of any information related to this decision. These documents, the Free Speech Union reported, show that Farage’s “perfectly lawful views on Brexit, LGBT rights, the government’s Net Zero targets and many other contentious contemporary topics, were cited as evidence of the former UKIP leader’s ‘distasteful’ views, which ‘do not align with our values.’” The bank’s reputational risk committee felt all this provided grounds for “exiting” Farage, but the bank also referred to the fact that, although he had technically dipped below the financial threshold required by the bank, he continued to meet “the EC [economic contribution] criteria for commercial retention.”

Soon, Coutts received the first instalments of a painful lesson in democratic accountability, which is thankfully still a part of British public life. The Information Commissioner John Edwards issued a statement, reminding all banks that a hundred-year-old duty of confidentiality “would not permit the discussion of a customer’s personal information with the media.” He was followed by the Prime Minister, who said, “It’s not right for anyone to be denied financial services because they’re exercising their lawful right to free speech.” The Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, tweeted that, “The Coutts scandal exposes the sinister nature of much of the Diversity, Equity & Inclusion industry.”

Natwest & other corporates who have naively adopted this politically biased dogma need a major rethink . This is also an issue for the public sector too, which is why I’m reviewing our policies at the Home Office. 2/2

— Suella Braverman MP (@SuellaBraverman) July 19, 2023

Alison Rose, the CEO of NatWest and the leaker of the untrue information about Farage’s account, kept her job for only a few days. As the Financial Times observed, “Lawfully held opinions should not be a bar to a bank account. This is true of any individual, and other troubling cases have come to light since the Farage story broke.” This did not satisfy Farage, and he continued to demand further resignations. Amazingly, he got one, when the CEO of Coutts itself, Peter Flavel, decided that he could not retain his post.

Many Coutts customers have acquired their wealth through opaque channels, but in recent years, the bank has sought to fashion a progressive image for itself by adopting proactive positions on a range of issues, including climate change, support for Gay Pride and other LGBTQ+ matters. Alison Rose was at the head of those who wanted to rebrand the bank as highly progressive on issues of sexuality as well as climate change. During Pride week, Coutts’s glass frontage was emblazoned with a rainbow of colours and the slogan, “Coutts Bank with Pride.”

The Farage row is best understood as part of a growing and frequently ill-tempered debate about “woke capitalism.” The debate is most contentious in the US, where the phenomenon is more evident. In April this year, the drinks company Anheuser Busch, which markets Bud Light, agreed a sponsorship collaboration with a transgender influencer named Dylan Mulvaney. Sales fell for weeks as customers demonstrated their angry opposition to the deal, and the beer suffered a 23 percent drop in sales in May last year, while sales of Coors Light and Miller Lite increased sharply. A company spokesman maintained that Bud Light was still America’s favourite light beer over the year, but he did not deny the slump.

The company found itself caught between those who supported the Mulvaney endorsement and those who vehemently opposed it. In a statement, the company’s CEO Brendan Whitworth said, “We never intended to be part of a discussion that divides people. We are in the business of bringing people together over a beer." This only made matters worse, since Whitworth’s perceived capitulation to the protestors succeeded in irritating Mulvaney’s supporters.

As in the case of Coutts, the politicisation of corporations can usually be traced to the beliefs of a senior executive. It usually comes down to a decision, often at board level, to position products where publicity will make a splash, thereby increasing visibility even if an initiative generates controversy. In his book, Woke Inc., the US entrepreneur and 2023 Republican presidential contender Vivek Ramaswamy argues that three steps are necessary for introducing a product: first, a relative straightforward market; second, an opportunity for a successful arbitrage—that is, buying relatively cheap and selling relatively dear; and third, “pretend like you care about something other than profit and power, precisely to gain more of each” (his italics). He continues more sternly:

I’m fed up with corporate America’s game of pretending to care about justice in order to make money. It is quietly wreaking havoc on American democracy. It demands that a small group of investors and CEOs determine what’s good for society rather than our democracy at large ... it’s concentrating power to determine American values in the hands of a group of capitalists rather than in the hands of the American citizenry at large.

Ramaswamy is right on this. Companies need to do a number of things in order to be good citizens. They should pay their workers well. They should avoid vast payments to their top executives, who are able to write their own pay checks. They should pay their taxes and not seek to use havens. They should not pollute. They should ensure their products are worth the price they command. They should be honest. But they should not prescribe a particular form of ethics.

Coutts has shown bad corporate behaviour in the past. In 2012, it was fined £8.75m for breaching money-laundering rules, exposing it to the risk that it was handling stolen money due to its failure to monitor and properly deal with customers liable to be corrupt. A few months earlier, the bank had been fined for recommending an American fund that invested in risky asset-based securities, and it was directed to compensate all customers who suffered losses.

The Farage affair is worse than those instances of a bank occasionally ignoring regulations in search of profit. The dossier which Farage recovered from the bank showed that it had trawled through reports and commentary which described him as racist, xenophobic, and chauvinistic—largely because of his campaign against continued membership of the EU—and claimed that his rhetoric promotes violence against immigrants. These accusations are one-sided and questionable—the dossier does not, for instance, include Farage’s resignation from UKIP in 2018, because its new leader Gerard Batten developed a “fixation” on the dangers of the British Muslim community and employed the far-Right activist Tommy Robinson.

The Coutts-Farage affair provides a warning of how ultra-progressivism, when endorsed by those in positions of power, can become authoritarian. The dossier was a polemic rather than a sober report examining Farage’s continued membership. The bank had flouted its duty to provide services to someone who, however controversial and disliked, had a right to his opinions and activism.

The voices arguing that there are weightier, more urgent issues than this kind of culture war are correct: the taste, in many parts of the world, of what the UN Secretary General has called “global boiling” demonstrates that, as do the renewed fears that a war between two Slav nations could end us all. Nevertheless, we need not neglect a broken leg for fear of cancer.

The dictatorial possibility tucked inside the commitment to “inclusivity” has rebounded, satisfyingly, on the perpetrators. But it has also demonstrated the depth of the urge to control and punish those whose opinions make them suspect to powerful figures who merge corporate power with the construction of a new form of morality beyond the possibility of discussion, let alone disagreement.