Education

And Yet it May (Or May Not) Move

If we allow ideological campaigns to discourage controversial research, we will be making a terrible mistake.

In January, Cleveland State University concluded a nine-month investigation into allegations of “academic research misconduct” made against me by outside parties. The investigative committee found me guilty on four counts and the administration determined that these constituted grounds for dismissal. Two months later, the university officially terminated my employment.

Until then, I had been a tenured full professor with top departmental seniority. I was even unionized. I had earned my bachelor’s degree and two master’s degrees at CSU, and my presence at the university dated back to 1986, as either a faculty member or student. For evidence of my teaching ability, interested readers can consult the evaluations I received from Rate My Professors. Of the 234 class sections I taught, a fraction were at the University of Akron, where I earned a PhD in psychology in 1998. The rest were at CSU.

As a researcher, a colleague once remarked that I was an “average social scientist.” I agreed. To date, my work has been cited 1,315 times in academic literature—my h-index is 17 and my i-10 index is 26. It is not hard to find academics with a much higher output than this. But whatever my standing among my colleagues, I’d published more than enough for CSU to grant me tenure in 2010, and to promote me to full professor in 2016.

The experience of being fired was distressing. Worse, the circumstances of my termination mean that I am no longer employable anywhere as a college professor. Fortunately, I was able to cash out a decent pension (after absorbing the early withdrawal penalty), and my lawyers and I are preparing to file a federal suit against CSU for wrongful termination.

From Allegation to Investigation

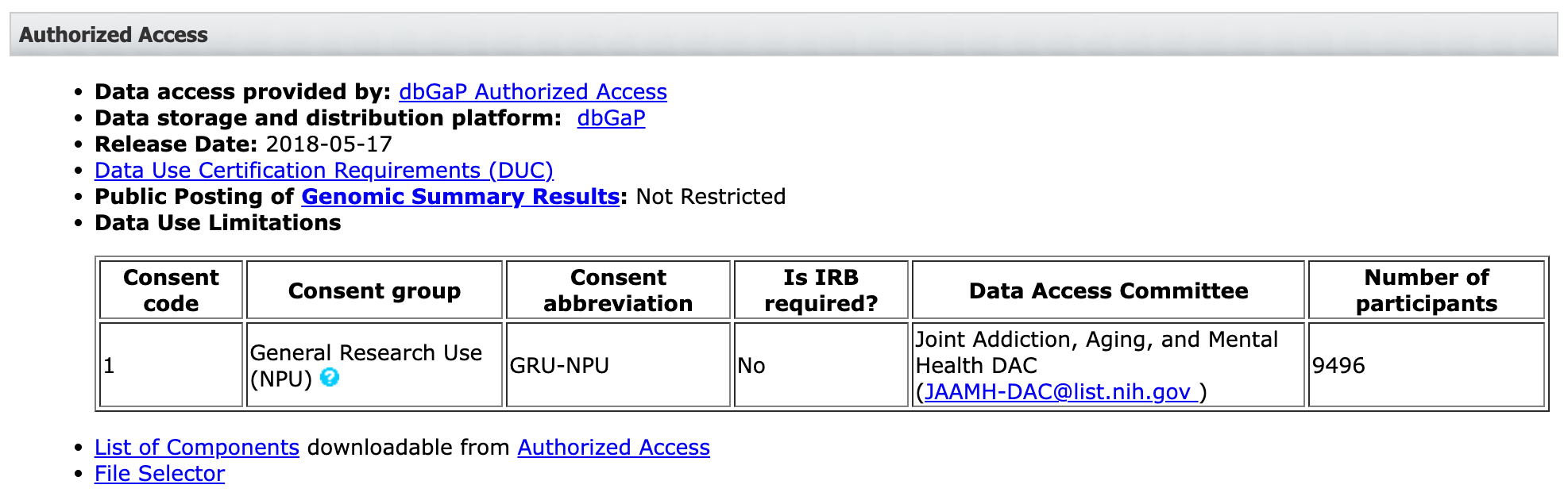

The CSU investigation related to an article that colleagues and I published in the peer-reviewed journal, Psych, on 30 August 2019, titled “Global Ancestry and Cognitive Ability.” Our research topic was (and remains) among the most controversial in all of science: Do genes play a non-trivial role in producing the persistent racial “gaps” between average IQ test scores? For the purposes of our study, I filed two applications with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) requesting access to the Trajectories of Complex Phenotypes (TCP) dataset held on their database of Genotype and Phenotype (dbGaP). Following analyses of these data, we concluded, “Results converge on genetics as a potential partial explanation for group mean differences in intelligence.” [Emphasis added]

Our study did not receive much publicity between the time it was published and the day I was fired, but the publicity it did receive was mostly positive. Russell Warne’s 2020 book In the Know: Debunking 35 Myths about Human Intelligence cited it (in Chapter 28) as an example of evidence that group differences in average IQ scores may not be caused solely by environmental factors. Our findings also stimulated in-depth discussions on Twitter and Reddit. While these discussions featured some criticisms, the overall consensus seemed to be that our study was rigorous and well-designed.

Not everyone was impressed, however. In September 2019, four academics from outside CSU co-signed an email to my university president and another to the NIH alleging a series of ethical violations and instances of procedural misconduct. The NIH opened an investigation into the possible misuse of its data and emailed me on 29 September requesting a response to the allegations which I promptly provided. They also asked me to refrain from publishing further papers that relied on these data. There was then a long silence, during which time the NIH continued to approve our data access requests. In the absence of further communication, we assumed they had accepted our explanation and we remained in good standing with the institution.

On 6 April 2021, a fifth academic emailed the CSU president alleging that the purpose of our research was both unethical and a violation of the NIH data use agreement by its very nature. He also wanted to know if our proposal had been approved by an Institutional Review Board, and contacted two NIH officers with his concerns.

On 27 May 2021, a year-and-a-half after the NIH first contacted me for a response to the allegations, the NIH’s deputy director of extramural research finally wrote to me and to CSU to report the results of their investigation. I was judged to have violated the NIH data use agreement on three counts: (1) I had used the dbGaP’s TCP dataset for purposes other than those specified in my application; (2) I had uploaded “coded” versions of some of that dataset to an unauthorised server; and (3) I had failed to notify the NIH of the publication of our Psych article in my annual progress reports.

The penalty was an unprecedented three-year ban on accessing dbGaP data. One of my co-authors and I lodged an appeal on 11 July. This was rejected on 17 August in a letter from the NIH upholding their original judgement and reaffirming the sanction. That letter also alleged a fourth violation—that my co-author was refusing to destroy the dbGaP data having been instructed to do so by the NIH. These findings would form the basis of CSU’s investigation into alleged academic misconduct.

The CSU Investigation

On 26 July 2021, CSU’s Research Integrity Officer (RIO) sent a letter to the CSU academics charged with investigating these allegations against me. The three committee members empanelled the previous month were, respectively, a professor of psychology, a professor of criminology, and a professor of social work. In advance of my appearance before the committee, I requested that an expert in genetics be included on the panel. That request was denied.

The charges I was facing were potentially serious, since misusing NIH data can make the research participants personally identifiable to any outsider with the numbers, the appropriate expertise, and a comparison DNA sample needed to find a match in the data. I appeared before the panel and answered their questions. The five academics who had submitted complaints about my conduct were then all interviewed by the committee. CSU did not allow me to submit questions for any of the external witnesses who levied serious complaints against me, even though Section III.C of the university’s internal policy (not to mention a commitment to basic fairness) clearly requires that I should have had that right. Indeed, I wasn’t even aware that these witnesses were being interviewed until CSU sent me the Zoom transcripts and invited me to respond to their testimony in writing and during my second interview.

During this process, I was able to refute many of the allegations made by the outside academics in their original complaints and during the course of their interviews, many of which were irrelevant to the question of alleged academic misconduct at hand. In what follows, I will explain why I believe the remaining four charges of which I was eventually convicted were flawed.

Charge 1. Unauthorised use of controlled-access data.

This charge covered the first two violations alleged by the NIH—that I had used their dataset for purposes not described in the data access request, and that I had uploaded some of that dataset to an unauthorised server.

The first part of this charge is simply false. On 15 July 2018, I submitted a data access request for Project #19090, in which I stipulated that the data would be used “to determine if global ancestry predicts mental health outcomes.” Like the NIH, the committee concluded that this was inconsistent with the subject of the paper on race and intelligence we published in Psych. Both appeared to assume that I had deliberately misled the NIH because I was afraid that, had I been candid about my intentions, they would not have approved our use of the dataset.

But on 19 September 2018, I had submitted a second application (Project #19747) requesting access to the same TCP dataset, which read in part:

For these analyses, we will need cognitive data (all available) … The study will be a correlational analysis of the statistical association between various PGSs [polygenic scores] and cognitive ability. We will conduct analyses separately in White and African American samples. For these analyses, we will need cognitive data (all available) to create general and broad ability indexes, and demographic data (age, sex, etc.). [Emphasis added]

This second application was approved. If my intention was to deceive the NIH about the purpose of my research, this was a strange way to go about it. The actual explanation for the apparent discrepancy between the two data requests is perfectly straightforward—following approval of application #19090, the focus of our research changed. So, to reflect that change in focus, and to comply with the applicable rules and regulations, I submitted application #19747. This was an attempt to be transparent, not deceptive. As I explained to the NIH when they asked about it in 2019, my colleagues and I felt both applications covered the intelligence project, but that even if #19090 did not, #19747 explicitly covered the intelligence component of the project.

The second part of this charge—that I had uploaded some of the data to an unauthorized server—was my only blunder, but it was an honest oversight. The CSU report states, “uploading of these controlled data or derivatives seriously deviates from common research practices and was done knowingly.” [Emphasis added]

Yes, I knowingly uploaded the data, but I did not know that it was a violation of the data use agreement, still less a serious one. We found the NIH’s language, from application to closeout, to be rather ambiguous, although we did make a sincere effort to comply throughout. These data were non-identifying and demonstrably posed zero risk of exposing any research participant’s identity. Furthermore, as I pointed out to the committee, the NIH subsequently approved other researchers’ use of this same server, thereby demonstrating that it posed no security risk. Although my mistake caused no harm, I now know that I should have secured NIH approval before uploading any of their data to the external server. During my interview with the committee, I acknowledged this lapse and apologized.

Since securing approval to upload the data to this server would have been straightforward, I had no motive for failing to do so besides honest error. This was not even raised as a matter of concern by the NIH in the fall of 2019 when they first received the complaint about our use of the dataset. It was not until May 2021—a year-and-a-half later—that we learned that this was something we were required to report. Had the NIH genuinely believed that the use of this server posed even a remote risk of harm or identification, it is reasonable to suppose they would have instructed us to take it down as a matter of urgency, which they did not.

Charge 2: Publishing without NIH permission

The story here is somewhat complex. Before I discovered that our Psych study had landed me in trouble, one of my students (a co-author on the Psych paper) and I prepared a follow-up study using the same NIH dataset. My student posted a copy of the preprint to an Internet website, on which I was listed as a co-author.

On 4 February 2020, my student contacted the NIH and asked two questions: (1) Could he submit the completed preprint manuscript for publication in a peer-reviewed journal? (2) Could he pursue new research using the TCP dataset? An NIH representative replied to only the second of these the following day, stating, “You can NOT use that particular data set for your research.”

The student wrote back seeking clarification: “I wish to confirm before submitting that, in doing so, I am in no violation with dbGaP policy. In absence of a reply detailing the violations, I will assume there are none and submit the paper.” He received no response. He then contacted the JAAMH DAC Committee, and then NIH Science policy, seeking additional guidance and received no reply from them either.

Since these data had already been analyzed, my student reasoned that the NIH had no authority to tell him what to do with the results and submitted the paper for publication. Since the NIH had instructed me not to publish any further papers based on these data until further notice, I asked to have my name removed as co-author before publication in a good-faith attempt to be cooperative.

In retrospect, it would have been better to await explicit permission. The NIH did not list the publication of this paper among the alleged violations of their contract in their two emails during the summer of 2021. Nevertheless, CSU convicted me of publishing a paper that I did not publish, and on which I was no longer even listed as an author.

Charge 3: Failure to receive IRB approval

The allegation that I had failed to secure Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval before conducting the study was the most peculiar of the four charges of which I was convicted. The IRB is a committee internal to CSU, which evaluates faculty research proposals to ensure the fair and ethical treatment of research participants. I am well acquainted with this committee’s function and importance because I served on it in the 1990s.

As the CSU report acknowledges—and as the NIH website unambiguously states—internal IRB approval is not required for researchers applying to use this particular dbGaP dataset:

However, the committee determined that I needed to seek IRB approval anyway because I had violated NIH’s data-use agreements by uploading some of the data to an external server, an action that is not protected by the dbGaP data-use policy. But since the NIH did not conclude that my use of that server had been a violation of the policy and had approved its use by other scholars, I’m at a loss to explain how it could have required IRB approval. In any event, had I realized that the use of a server was not covered by the standard data use agreement, I would have re-engaged with the NIH not the CSU IRB, since these were NIH data.

Charge 4: Unauthorised research funding

On this count, CSU convicted me of behavior governed by no existing policy, rule, or regulation. Via word of mouth, we learned that some private citizens were interested in making donations to help fund our research. To cope with demand, we decided to create a non-profit organization called The Human Phenome Diversity Foundation (I did not choose the name) to handle the donations. CSU convicted me of “unauthorized research funding,” but refused to specify the policy, rule, or regulation I had violated, despite my repeated requests for clarification.

Dismissal

The instructions issued to the committee stipulated that a finding of academic misconduct not only required a determination that I was guilty of “a significant departure from accepted practices” but also that my conduct was committed “intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly.” These words are not synonyms for negligence or carelessness, they require deliberate and wilful violations.

While I made mistakes during this process, I maintain that I never “intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly” misrepresented my intended use of dbGaP data, used that data to pursue unethical research activity, or improperly shared controlled-access data. Nor were any of the research subjects included in the data ever at any risk of identification or harm. My attempts to explain all this during my two interviews and in a rebuttal submitted in response to the draft report were in vain.

On 13 January, the same day that the committee released its report, the CSU provost wrote to me concurring with its conclusions. “I do not know,” she admitted, “if these violations were committed knowingly or recklessly. I do not distinguish between these two states of mind in interpreting the actions of a tenured full professor who should be well informed about appropriate research practices prior to seeking to serve as a Principal Investigator on a research project.”

In other words, the standards expected for a determination of academic misconduct had not been met. Nevertheless, she notified me that an ad hoc committee would be formed to consider her recommendation of dismissal. The outcome of that hearing was, by this stage, a foregone conclusion. I was formally fired on 4 March.

Settled Science

Throughout the process, CSU was at pains to emphasise that they were not concerned about the content of my research. The committee members and provost maintained that they were only interested in the instances of data misuse alleged by my accusers and the NIH’s investigation. The academics who first reported the allegations of misconduct to the NIH and the CSU president, on the other hand, made no secret of their antipathy to our research topic. “I pay attention to racist applications of genetic data,” one of them told the committee when invited to explain his interest.

Nor were they the only ones to announce that my research had been ethically unacceptable. Following my dismissal, the Chronicle of Higher Education ran a lengthy article about my case beneath the headline, “Racial Pseudoscience on the Faculty.” The article portrayed me in a deeply unfavourable light, and though the author didn’t explain what was empirically wrong with our paper, she plainly regarded it as self-evidently monstrous. A similar pattern was repeated in most of the Twitter commentary praising CSU’s decision to fire me. An anthropology blog summarised my predicament in this way: “At no point did anyone actually dispute his findings. It was simply taken for granted that they could not be true.”

With that in mind, I would like to take a moment to defend our research and to explain why I believe it is not just valid but also important. Controversies like this one tend to raise two related questions in the minds of casual observers. First, why would any non-racist person look for possible genetic links between race and average IQ test scores? And second, what does the researcher in question personally believe to be the cause of racial IQ gaps?

A great deal of data now clearly indicate that human wellbeing and IQ are correlated, often closely. In Chapter 10 of Michael C. Ashton’s textbook, Individual Differences and Personality, the author discusses several important outcomes that are influenced by a person’s general intelligence, as measured by IQ tests. These include academic achievement (such as grades and SAT scores), job performance, income, criminality (or lack thereof), and even various measures of health, including longevity. Ashton discusses all this in a section entitled, “mental ability and life outcomes.” Similar summaries also can be found in Chapter 3 of Stuart Ritchie’s Intelligence: All the Matters (2015), and in Chapters 7 and 8 of Ian Deary’s Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction (2020). These are all uncontroversial and widely respected books.

IQ’s predictive power is especially pronounced when the data are aggregated to groups of people versus individuals. For example, in another paper, colleagues and I estimated the average IQs for each of the 50 US states. Our “state IQ” scores predict almost every important state-level outcome, from education and income levels for a state to crime and health rates. I am not confusing correlation with causation in these data (nor am I committing ecological fallacies), though I personally believe that IQ/wellbeing effects are bidirectional.

It is also now widely accepted that IQ tests predict important outcomes independent of the test taker’s race or ethnicity. In other words, professional IQ tests do not exhibit cultural bias. This conclusion has been endorsed by both the National Academy of Sciences (in the 1980s) and the American Psychological Association (in the 1990s). An up-to-date review published last year concluded, “while more research is necessary, the current evidence largely supports the proposition that most commercially developed widely use[d] tests of achievement and aptitude are not culturally biased.” Here is the APA’s report on this point:

Intelligence tests predict school performance fairly well, at least in American schools as they are now constituted. Similarly, achievement tests are fairly good predictors of performance in college and postgraduate settings. Considered in this light, the relevant question is whether the tests have a “predictive bias” against Blacks. Such a bias would exist if African-American performance on the criterion variables (school achievement, college GPA, etc.) were systematically higher than the same subjects’ test scores would predict. This is not the case. The actual regression lines (which show the mean criterion performance for individuals who got various scores on the predictor) for Blacks do not lie above those for Whites; there is even a slight tendency in the other direction (Jensen, 1980; Reynolds & Brown, 1984). Considered as predictors of future performance, the tests do not seem to be biased against African Americans.

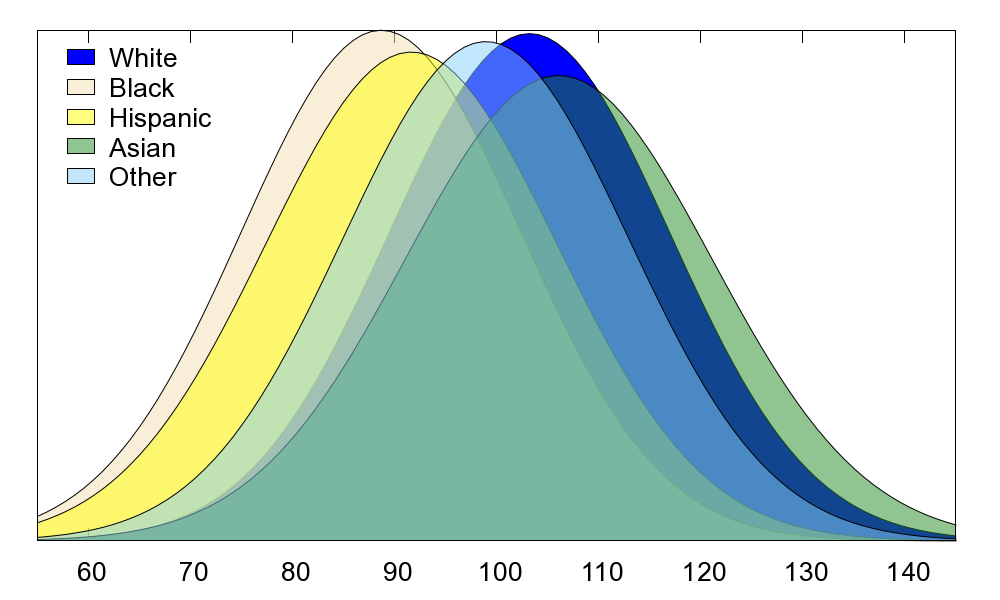

Every study I’m aware of (going back approximately 100 years) has shown differences in average IQ test scores by race or ethnicity. Please note, I refer here only to the existence of these differences, not to any potential explanations for why they may exist, which remain uncertain. As part of the supplementary material for his recent book Facing Reality, Charles Murray assembled databases of all federally sponsored longitudinal studies and nationally representative studies which included data on racial gaps in IQ. These extend from the 1970s up to 2017. The collection of studies Murray compiled is probably the single most complete resource available to anyone who wants to examine the raw data in this area.

Another line of inquiry, consistent with those above, provides data from the standardisation samples that IQ test makers use when norming their tests. The purpose of test norming is to classify individual test results in relation to a representative reference population, so that (for example) a score of 100 indicates the 50th percentile (the median score).

Note that the IQ score distributions for all demographic groups overlap considerably; it is only the averages that differ. It is therefore never appropriate to infer an individual’s IQ score from his race.

The predictive power of IQ, regardless of a subject’s race or ethnicity, and the existence of group differences in average IQ scores are both now completely uncontroversial among psychometricians. A psychologist who continues to dispute or deny either conclusion would be comparable to a climatologist who denies that our planet is warming. However, outside of psychology, where researchers might be unfamiliar with the IQ literature, it is still not considered acceptable even to discuss these issues, let alone conduct new research. I believe that the price we will pay for persisting in ignorance is morally unacceptable.

In the past two years, US federal, state, and local governments have implemented racially exclusive stimulus and basic-income programs. This means that members of some racial groups are not eligible for their benefits. As described in the articles just linked, the federal policies explicitly state that their benefits are only available to “socially disadvantaged” ethnic groups, while the local policies state that they are only available to BIPOC (black, indigenous, and people of colour).

Some of these policies may not survive recent legal challenges to their constitutionality. However, it is important to understand that they are informed by an assumption that whenever a racial disparity exists in some socially important area (e.g., income), racism must be the sole cause. Racially discriminatory policies are therefore justified as necessary corrective measures. The related beliefs that racism is the only possible explanation for disparities in outcomes, and that “positive discrimination” is the only solution, are perhaps most famously expressed by Ibram X. Kendi in his influential polemic, How to Be an Antiracist.

Kendi’s beliefs may or may not be true. But when governments use his premises to justify racial discrimination (even if that discrimination is against more “advantaged groups”), it is essential that those premises can be critically examined by scientists. This is not just a question of whether the Biden administration’s racial policies are morally justified. If racial disparities are in fact caused by something other than racism, then policies like these will fail to solve the problem of disparities. Judging from the amount of public attention they’ve received in recent years, the existence of race differences in average human wellbeing is among the most pressing problems faced by America today. If we wish to fix a problem, we must be able to identify its causes. That is axiomatic.

As to what I believe is causing racial gaps in average IQ scores, I remain agnostic. I do believe that relatively extreme environmental conditions (such as very poor nutrition) will lower IQ, but I know of no environmental variable that can raise an individual’s IQ in the long run. Surprisingly, controlled studies looking at the most obvious environmental factors that might explain average differences, such as differences in motivation, vocabulary, or socio-economic status, have found that these factors do little to explain the gaps (the APA report cited above arrived at the same conclusion).

Conversely, the study we conducted potentially implicating genes as a partial cause is not enough for me to abandon my agnosticism. Some have called me a weasel for continuing to take this position, but if I am to get off the fence, several more large-scale studies are needed from independent researchers that replicate and expand upon the effects we may have uncovered.

I also believe, as Steven Pinker argued in The Blank Slate, that equality of treatment and opportunity for all must not be asked to rely on an empirical claim about human sameness. Not only does this incentivise the suppression of contradictory findings, but if the empirical claim that humans are biologically uniform is found to be false, then the ethical basis of equality will collapse.

Instead, our commitment to equality must rest on the moral principle that every person deserves to be treated as an individual, not as a group representative. As E.O. Wilson put it in On Human Nature, “We are not compelled to believe in biological uniformity in order to affirm human freedom and dignity.” The US policies discussed above suggest that when the existence of group differences in average ability is rejected, racial discrimination is just as likely to increase as to decrease.

The Nature of Our Study

So what did our study investigate and why were its conclusions considered so provocative? In a nutshell, we found that when self-identified “race” is statistically controlled for, IQ still correlates with “biogeographic ancestry,” as measured using genetic tests. “Biogeographic ancestry” is a ubiquitous variable in genetics research that refers to the geographic location(s) from which most of a participant’s distant ancestors came. This variable has important real-world applications, like testing whether disease susceptibility covaries with a person’s ethnicity.

Our findings may yet turn out to be significant, because we attempted to separate “race” as a human construct from biological ancestry. Factors such as racial discrimination, culture, and quality of education have all been suggested as possible environmental causes of group differences in average IQ. Yet all of these factors vary according to self-reported racial identity rather than biogeographic ancestry. By controlling for racial identity, our study theoretically controlled for the social advantages and disadvantages that go along with “race.”

Our study also controlled for the set of alleles that are known to affect skin tone, and found that this does not reduce the size of the correlation between ancestry and IQ. (We did this using the data we uploaded to the external server, as described above.) This was to ensure that when measuring the correlation, our results were not confounded by individuals with darker skin possibly enduring greater discrimination (colourism), which could then potentially depress their IQs.

When people state that “race is just a social construct,” I agree. But race is also correlated with the underlying reality of global genetic variation. As John Relethford has explained, race is “a culturally constructed label that crudely and imprecisely describes real genetic variation.” Our study’s results suggest that group differences in average IQ scores are not truly “racial” in nature. Based on our results, variation in average IQ is not directly related to race, but average IQ scores do vary with biogeographic ancestry. The reason average IQ scores appear to vary with race is likely because “self-identified race” correlates strongly with one’s “biogeographic ancestry.”

Psychologists have been suggesting for over a decade that a study of this kind ought to be conducted, and in 2005, David Rowe gave a detailed summary in the APA’s flagship journal American Psychologist of what such a study should involve. However, until the past few years, genetic ancestry tests were too expensive for a study with a large enough sample size to be feasible. Unfortunately, by the time technology had advanced enough to conduct such a study, the political conditions had made it socially hazardous.

I do not expect anyone to accept my results without question. That is not how science works. What I do expect is that instead of restricting access to the databases that can be used to conduct such research, or adopting new publication standards in academic journals so that such research can no longer be published, critical scientists test for themselves whether our findings can be replicated. (I have replicated them once myself with a different dataset, although this second study has not been published.) Many apparently promising ideas (such as cold fusion) were ultimately rejected after it turned out that they were impossible to replicate. I’m happy to accept that my own study is a meaningless fluke, but only if my critics can show that it cannot be replicated with rigorous methods and large samples.

Why Academic Freedom?

Research on racial gaps in IQ is now commonly regarded as the most dangerous topic for any academic to study, and my experience has done nothing to disabuse me of this notion. Whatever the priorities of the NIH and CSU investigators, were it not for the ideologically motivated complaints they received, none of what followed would have happened. If society responds to future campaigns of this nature by discouraging research of this kind, it will be making a terrible mistake.

If society were totally colourblind, group differences in average cognitive ability would not have much social importance, because in such a society, only people’s abilities as individuals would matter. But that isn’t the society in which we live. Even though our society generally ignores the average group differences produced by IQ testing, we are preoccupied with racial disparities in many of the areas where IQ predicts success, such as in SAT scores, admission to top-tier colleges, and representation in lucrative, high-status jobs.

Some of the proposals suggested to address these disparities go much further than the steps our government has already taken, such as a proposal made in the Washington Post that the weight of an American’s vote should vary depending on their race, or Ibram Kendi’s proposal for a new government agency devoted to eliminating racial disparities throughout American society. The question of how to address racial disparities in university admissions is now before the US Supreme Court. When a social question is important enough to be heard there, isn’t it also important enough for scientists to carefully examine every relevant line of data?

There is also a more fundamental problem with arguing that some topics are too dangerous to study, or that some hypotheses are too dangerous to test. The idea that some areas of inquiry should be off-limits has been stated explicitly when other researchers have been denounced for similar reasons. But in a 1978 paper published in Nature, Bernard Davis explained better than I can why this attitude is mistaken:

Ever since the discovery of fire, and of cutting tools, it has been clear that virtually any scientific knowledge can be used for good or for ill: the costs and benefits depend entirely on how it is used. Moreover, we have only a very limited ability to foresee the eventual scientific benefits of a new discovery: science is a continuous web, and fundamental advances often arise through unexpected cross-fertilisation. For example, there are very good reasons to forbid human cloning: but if we should forbid any research in cell biology that might bring cloning nearer we would seriously impair advances in cancer research. We must therefore ask whether it is more rational to try to protect society by limiting the areas open to fundamental inquiry, or by focusing on earlier assessment and improved control of new technological applications of scientific knowledge.

In principle, the purpose of tenure at universities is to allow academics to research whatever questions they believe to be important, without having to fear for their livelihoods. But I was fired despite having tenure, on the basis of allegations intended to pressure and embarrass two institutions with the power to destroy my career. This was not simply an unjustified attack on my reputation and my ability to continue working as a researcher; it was an affront to the principle of academic liberty upon which science depends for its legitimacy and survival.