Arts and Culture

Go Ask Beatrice: Notes on a Dishonest Decade

An outstanding new book tells the story of a wildly successful literary hoax. But it was just one of many.

I.

Go Ask Alice, purportedly a first-person account of an anonymous American teenage girl’s descent into drug dependency, was published in 1971 and became an immediate hit. The paperback edition, published 50 years ago in 1972, became an even bigger publishing phenomenon. By 1979, it had already been reprinted 43 times, making it a mainstay on the American Library Association’s lists of best-ever Young Adult books. In 1982, the New York Times reported that it was also “the most frequently censored book in high school libraries, according to a survey of librarians.”

The book has never been out of print and has sold roughly six million copies in the United States, roughly twice as many as Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, which was published in the same year. Its influence was huge. It set off a demand for teenage diaries that real diaries couldn’t possibly supply, so fiction writers stepped in to fill the vacuum. Over the next decade or so publishers brought out Paul Zindel’s The Amazing Death-Defying Diary of Eugene Dingman, Joan W. Blos’s A Gathering of Days, Robert C. O’Brien’s Z is for Zachariah, Sue Townsend’s The Secret Diaries of Adrian Mole and its sequels, John Marsden’s So Much To Tell You, Hila Colman’s Diary of a Frantic Kid Sister and its sequel Nobody Has to Be a Kid Forever, and dozens of others. Throughout the 1970s and well into the 1980s, countless Young Adult novels were published with covers that mimicked the artwork of Go Ask Alice, which featured a gloomy portrait of a troubled girl.

Much as Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film Jaws is credited with inventing the summer blockbuster, Go Ask Alice is often credited with inventing the Young Adult literary phenomenon that would later give us such bestsellers as the Harry Potter series, the Twilight series, and The Hunger Games series. In early July of this year, the podcast You’re Wrong About… devoted three episodes to the book. Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, Esquire, the New Yorker, the New York Post, and other publications have published long essays about it recently. But they didn’t come to praise. They came to denounce.

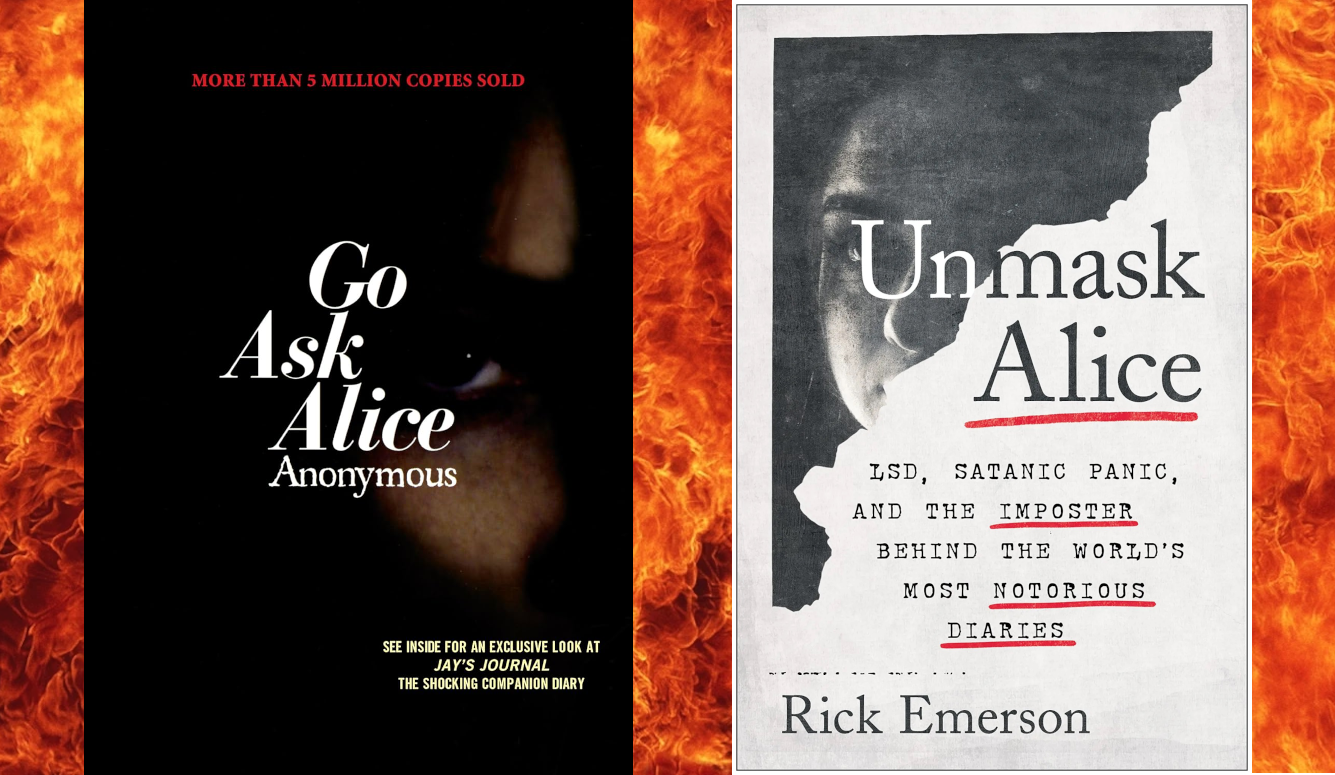

Rick Emerson’s recently published book, Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries, has exposed the true story behind Go Ask Alice and the fraudster who wrote it. As it turns out, it was not the diary of an anonymous American teenage runaway. It was a work of fiction written by a Mormon youth counselor named Beatrice Sparks, who was 54 years old when the book was published. The true story that Emerson tells is far more fascinating than the fake one Beatrice Sparks told.

Born Beatrice Ruby Mathews into an impoverished Mormon family in 1917, Sparks grew up in Logan, Utah. Her childhood was disfigured by sorrow and loss (her father abandoned the family when Beatrice was 12). Beatrice left home at 17 for California, where she wound up waiting tables in a Santa Monica restaurant. She made the acquaintance of another Mormon who had dropped out of high school, a young man named LaVorn Sparks. They married six weeks later and moved back to his home state of Texas. The early years of the marriage were marked by tragedy and heartbreak (a child dying at six days old, a house fire that destroyed all their belongings), but by the mid-1940s, things finally began to look up for the young couple. LaVorn was an early investor in some Texas oil fields that became hugely profitable. Soon the family was wealthy and, like Jed Clampett and his kin, they moved (back) to sunny Southern California.

You might think that the end of her economic woes would have made Sparks a happy and satisfied woman. It did not. Like a lot of young dreamers, she grew up believing she was destined for fame and glory. Her twin goals were to become a mental health professional and a writer. Alas, poverty had kept her from ever gaining a college education, but nothing could stop her from writing. In California, she cranked out copy for all kinds of third-rate publications—church bulletins, local newspapers, the California Intermountain News—often earning no money for her work and writing under a variety of pseudonyms. In the early ’50s she collaborated on a theatrical venture with Joseph Barbera, famous as one half of the team (with William Hanna) that had created the Tom and Jerry cartoon franchise for MGM studios. Together Sparks and Barbera wrote a play called The Maid and the Martian, which ran for seven weeks at a Los Angeles theater. A critic for the Los Angeles Times noted that the play “has strong elements and might even go to Broadway … provided it gains more completeness in plot and situation.”

Sparks thought her career as a writer was about to take off. Alas, Barbera soon decided he preferred producing animated stories to live ones and he dropped the project. Years later, in 1964, American International Pictures released a film loosely based on The Maid and the Martian called Pajama Party starring Annette Funicello and Tommy Kirk. Barbera had sold the studio the rights to the story without mentioning Sparks’s involvement. She was now 45 years old, living back in Utah (albeit in a 16-room Provo mansion), and beginning to despair of ever achieving success as a writer. Her salvation would come from a wholly unexpected source.

At 10am on October 4th, 1969, tragedy struck the family of entertainment industry superstar Art Linkletter. Linkletter’s 20-year-old daughter, Diane, jumped to her death from the sixth floor of the Shoreham Towers apartment complex in Los Angeles, where she lived. Understandably, her father didn’t take it well. Like a lot of parents whose children commit suicide, Linkletter felt tremendous guilt, which he tried to deflect by blaming others for Diane’s death. Despite the fact that an autopsy turned up no evidence of drug use, he claimed that she had been killed by drug pushers who supplied her with LSD. Her death occurred just a few months after the Tate-LaBianca murders committed by the Manson Family, whose members were also users of LSD. All of middle-class America, and especially middle-class Southern California where LSD seemed to be everywhere, was suddenly convinced that the drug could turn its children into monsters. Within weeks of Diane’s death, Linkletter was at the White House, urging his friend Richard Nixon to declare a war on drugs, and Nixon was happy to oblige.

Meanwhile, back in Provo, Beatrice Sparks had an idea. Passing herself off as a UCLA-trained psychiatrist, she contacted Art Linkletter and told him that she had come into possession of a diary kept by a middle-class teenage girl who had become hooked on drugs and died at the age of 17. Sparks suggested that, if she were to give the diary a light edit, it might be publishable as a book that would help teenagers and their parents understand the horrors of drug abuse. Intrigued by the idea, Linkletter connected Sparks with his publishing house, Prentice Hall. The firm’s editors were keen.

Of course, Sparks had never attended UCLA (or any other university) and was not a certified mental-health therapist. She had, however, worked as a voluntary counselor one summer at a retreat for Mormon girls organized by Brigham Young University. Inspired by letters from one of the troubled young attendees she had met there, Sparks managed to produce a fraudulent journal dusted with her working knowledge of psychiatric jargon. She wrote it out on various scraps of paper and random diary pages, sent it off to Prentice Hall, and soon the company was enthusiastically preparing to bring it to press. A youthful editor changed the title from “Buried Alive” (which Beatrice had chosen) to “Go Ask Alice,” a nod to “White Rabbit,” the 1967 Jefferson Airplane song about mind-altering substances inspired by Lewis Carroll’s novels (as a result, the teenage author of the diary is often referred to by reviewers and fans alike as Alice, even though she is unnamed in the book).

There was one catch, however. Sparks wanted the book’s cover to say, “edited by Dr. Beatrice Sparks.” But Prentice Hall thought a doctor’s name on the cover would scare away teenage readers. They opted for something simpler: “Go Ask Alice – Anonymous.” Once again, Sparks found herself erased from her own work. She threw a fit, but it did her no good and her agent advised her to take the money and shut up. And so, with no other options, she acquiesced. The book was published in 1971, became an instant classic of YA literature, and found its way into nearly every library in America (where it became one of the most frequently stolen books in the entire literary canon), as well as thousands of bookstores, and the shelves of countless teenagers’ bedrooms. But success only fueled its author’s anger and frustration. She had written one of the most talked-about books of the era, and yet her name was known to almost no one. She wanted fame. She wanted to be recognized as an expert on mental health. And yet, as far as anyone knew, she was just the wife of a fabulously wealthy Mormon oilman.

In 1978, Sparks got another big break. And just like the last time, it was the result of another family’s tragedy. In 1971, a 16-year-old Mormon teenager named Alden Barrett committed suicide after suffering from depression for many years. He left behind a diary that his parents discovered after his death. In 1977, Alden’s mother read an article about Beatrice Sparks in the Provo Daily Herald, which noted that she had helped shepherd the manuscript of Go Ask Alice into print. Mrs. Barrett and her family lived in nearby Pleasant Grove, Utah. Hoping to salvage something positive from Alden’s death, she contacted Sparks and gave her a copy of Alden’s diary. She said she didn’t want any money or credit; she just wanted Sparks to use Alden’s diary to spread the word about the danger of depression in vulnerable teenagers. Instead, Sparks did something horrible with it.

On January 1st, 1979, Simon and Schuster published a book called Jay’s Journal, the cover of which read: “Edited by Dr. Beatrice Sparks, who also discovered the international bestseller Go Ask Alice.” It consisted of 212 entries, only about two-dozen of which had anything to do with Alden Barrett’s original journal. With her uncanny ability to read the zeitgeist, Sparks intuited that a story about a kid who falls in with a gang of Satanic cultists would make for a more sensational story than a tale of teenage depression. And so she turned Alden Barrett, a lovelorn teenager whose greatest sorrow had been his parents’ refusal to let him continue his relationship with a girl he wanted to marry, into “Jay,” a teenager who drifts into a Satanic cult and becomes convinced he is being haunted by a demonic ghost named Raul.

The timing was impeccable. The book was published a month and a half after American cult leader James Jones convinced 909 members of his Peoples Temple to commit mass suicide in Guyana. Middle-class America was now as terrified of religious cults as they had been of LSD after the Manson murders. Sparks changed the main character’s name, but she left in just enough details so that anyone living in Pleasant Grove would know that the book was about Alden Barrett. Soon Alden’s family members were being accosted by well-meaning (and some not-so-well-meaning) Mormon neighbors wanting to know more about Alden’s descent into Satanism. “After failing to save Alden,” Emerson writes, “the Barretts now faced another horror: his rebranding as evil incarnate.”

II.

Unmask Alice is a brilliant piece of journalism and likely to be the most riveting piece of nonfiction published this year. The synopsis above only scratches the surface of the story Emerson has to tell. Nonetheless, the book lacks some important context. What it doesn’t reveal is that Go Ask Alice and Jay’s Journal were by no means the only fake nonfiction books to become cultural landmarks during the 1970s. They were not even the most egregious fakes—for some reason, the ’70s was a low and dishonest decade for nonfiction publishing in America. I don’t know exactly why this was, but I have a theory.

Back in the 1940s, both the fiction and nonfiction bestseller lists tended to be rather bland. But in the 1950s and early ’60s, Barney Rosset, the rebellious publisher and owner of Grove Press, embarked on a crusade to bring daring and transgressive fiction into bookstores across America. He intentionally published banned fiction titles such as D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, and sold these books through the mail, which was a federal crime. Then he went to court and fought for his right to sell whatever he wanted. Eventually, he won that fight, and by the mid-’60s American fiction began to look a lot more daring than it ever had, with salacious titles such as Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls, Harold Robbins’s The Adventurers, and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint topping the bestseller lists.

Sex novels began to pall after a while but, fortunately for the publishers, graphic horror and crime novels came along to fill the void, as books such as Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, and William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist became massive hits. With sensational novels like these on the fiction racks, it became difficult to attract book buyers to titles such as How to Avoid Probate (America’s bestselling nonfiction book in 1966) and Calories Don’t Count (number one in 1962). Nonfiction editors at American publishing firms were becoming second-class citizens as novels like Jaws and Love Story were racking up record-breaking sales figures. This may be why nonfiction editors at places like Random House, Simon and Schuster, and Prentice Hall began to push the envelope of what they were willing to call a “true story.”

As a result, much of the best-known nonfiction from that era has since been recategorized as fiction. The list includes Alex Haley’s Roots (according to Publishers Weekly, a top-10 bestseller in both 1976 and 1977), Forrest Carter’s The Education of Little Tree, and three books by Carlos Castañeda: Journey to Ixtlan (the ninth bestselling nonfiction work of 1972), Tales of Power (the sixth bestselling work of nonfiction in 1974), and The Second Ring of Power (the eighth bestselling work of nonfiction in 1977). Other books that are now widely regarded as more fiction than fact include Jay Anson’s The Amityville Horror (the 10th bestselling work of nonfiction for 1977), Charles Berlitz’s The Bermuda Triangle (one of the 10 bestselling works of nonfiction in both 1974 and 1975), and Sybil (the 10th bestselling work of nonfiction in 1973), all of which have been at least partially discredited. The decade’s most infamous work of non-fiction never even made it into bookstores. The Autobiography of Howard Hughes was wholly fabricated by Clifford Irving but, fortunately, exposed before it went to press. Irving spent 17 months in jail for his crime and had to repay a $750,000 advance. His wife also did jail time for her involvement in the fraud.

Alex Haley’s Roots: The Saga of an American Family is emblematic of how porous the wall between fiction and nonfiction was back then. The publisher, Doubleday, actually marketed it as fiction. Haley himself called it “faction,” but claimed it followed his own family’s history fairly closely. “To the best of my knowledge and of my effort,” he wrote in the book’s final chapter, “every lineage statement within Roots is from either my African or American families’ carefully preserved oral history, much of which I have been able conventionally to corroborate with documents.” Convinced by this claim that the novel was more fact than fiction, both the New York Times and Publishers Weekly chose to place the book on their nonfiction bestseller list. But trouble soon arose. Numerous historians came forward and identified errors in the book’s genealogy and history. Eventually, even Haley’s friend Henry Louis Gates Jr., a historian and literary critic, was forced to concede that, among professional history scholars, “Most of us feel it's highly unlikely that Alex found the village whence his ancestors sprang. Roots is a work of the imagination rather than strict historical scholarship.” But even as fiction it was assailed. Writer and folklorist Harold Courlander sued Haley for plagiarism, alleging that 81 passages were taken from his 1976 slavery novel, The African. The case was settled out of court when Haley agreed to pay Courlander $650,000 in damages and sign a statement acknowledging that some of Courlander’s passages had “found their way” into his book.

The first edition of Forrest Carter’s 1976 book The Education of Little Tree is described on the dust jacket as “A True Story.” It purported to be the childhood memoir of an Appalachian orphan raised by his Cherokee grandparents during the Depression. Eventually, the book was found to be more fiction than fact. Carter was not an orphan. Both his parents lived to see him grow into adulthood. Even worse, Carter was a hardcore racist who worked as a speechwriter for Alabama governor and staunch segregationist George Wallace in the 1960s. Even Wallace eventually distanced himself from Carter, finding him too radical for his taste. The Education of Little Tree remains in print but is now marketed as a novel, like Carter’s earlier book, The Outlaw Josey Wales (subsequently adapted for the screen by Clint Eastwood). Both are, to my mind, highly enjoyable books, but Carter’s history has tainted them forever.

The three Carlos Castañeda titles listed above were all immensely popular, especially among young people exploring alternate forms of spirituality, of which there were millions in the 1970s. But, according to Wikipedia, Castañeda “wrote that these books were ethnographic accounts describing his apprenticeship with a traditional ‘Man of Knowledge’ identified as don Juan Matus, a Yaqui Indian from northern Mexico. The veracity of these books was doubted from their original publication, and they are now widely considered to be fictional.” David S. Wills’s recent biography of Hunter S. Thompson makes it clear that much of Thompson’s so-called journalism was actually fiction. Sonny Barger, the recently deceased founding member of the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, claimed that much of Thompson’s first book, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, was fictionalized in order to make Thompson look tougher than he actually was. This trend continued throughout his career.

In 1972, the same year that Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was published, the eighth bestselling nonfiction book in America was A World Beyond, written by Ruth Montgomery. Montgomery claimed to have been the third sister of Lazarus in a past life, and a witness to Christ’s circumcision. Amazingly, the book is still in print and still categorized as nonfiction, but I doubt it would withstand the scrutiny of a vigorous fact-check. So, three of the most famous nonfiction books of 1972—Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Journey to Ixtlan, and A World Beyond—almost certainly contain more fiction than fact, even though two of the three were written by professional journalists.

In 1975, San Francisco socialite and TV personality Pat Montandon published a memoir called The Intruders, in which she claimed that during a 1968 housewarming party at a home she was renting in San Francisco’s upscale Russian Hill neighborhood, an irate Tarot reader placed a curse on the property. After that, all sorts of eerie and inexplicable things began to happen to her and to others who came to visit. As memoirs of the supernatural go, it is fairly tame fare. It even includes a 50-page appendix documenting her claims with notarized eyewitness accounts, police reports, fire department reports, and so on. The book ignited a demand for more of the same, and so it was followed in short order by Jay Anson’s better-known The Amityville Horror, published in 1977.

The Amityville Horror claims to be a factual record of incidents that occurred at a Dutch colonial home at 112 Ocean Avenue in the small town of Amityville, New York. No one denies that the house was the site of a grisly multiple murder on November 13th, 1974, when 23-year-old Ronald DeFeo Jr. killed six members of his family. A year later, George and Kathy Lutz purchased the house and moved in with their three children. They remained there for only 28 days, during which the Lutzes claimed to have been beset by all sorts of supernatural terrors. The couple documented their experiences by speaking them into a series of audiotapes that ran to roughly 45 hours of material. These were given to Anson, a journeyman nonfiction writer whose previous work had mainly been about the movie business. Anson embellished the Lutzes’ story (exactly how much is a matter of dispute) and produced a gripping haunted-house tale that would sell upwards of 10 million copies. The book was turned into a blockbuster 1979 film starring James Brolin and Margot Kidder that earned nearly $90 million on a budget of less than $5 million. DeFeo’s attorney, William Weber, later admitted that the book was a “hoax,” and that he and the Lutzes had “created this horror story over many bottles of wine.”

In 1976, the University of Arizona Press, a staid and reputable academic firm, published I Married Wyatt Earp: The Recollections of Josephine Sarah Marcus Earp. It was a huge success and for nearly a quarter of a century was regarded as authoritative. But the book has since come to be regarded as a literary fraud perpetrated by Glenn G. Boyer, and the University of Arizona has disavowed it. In 1971, Bantam Books published Erich Von Daniken’s Chariots of the Gods?, one of the first books to popularize the idea that ancient astronauts from another planet visited Earth in prehistoric times and influenced the development of humankind. Von Daniken even claimed that the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel described a spaceship in the Bible. Although its theories and assertions were dismissed outright by the scientific community, the book made the New York Times bestseller list and Von Daniken went on to write many other pseudo-scientific books, which have sold roughly 70 million copies combined. One of the scientists who set out to debunk Von Daniken’s book was Josef F. Blumrich. In the early 1970s, Blumrich worked for NASA at the Marshall Space Flight Center, so he knew as much about spaceships as nearly anyone alive at the time. While carefully reading the Book of Ezekiel in search of flaws in Von Daniken’s theory, Blumrich managed to convince himself that Von Daniken was actually correct. This “research” resulted in a 1974 nonfiction work titled The Spaceships of Ezekiel, which argued that the ancient prophet had actually communed with astronauts who arrived on Earth in a shuttlecraft after a long voyage from another planet.

In their 1978 nonfiction work, The Manna Machine, George Sassoon and Rodney Dale claimed to have found proof that ancient Israelites, during their 40-year sojourn in the desert, were kept alive by a food-making machine powered by a nuclear reactor hidden inside the Ark of the Covenant. Apparently, the machine would produce food for six consecutive days and then, on the seventh day, like an ice-cream maker at McDonald’s, it would have to be taken apart for cleaning and servicing. The authors decided that this is where the idea of the Sabbath originated in Jewish culture. In their 1974 book, The Jupiter Effect, authors John Gribbin and Stephen Plagemann argued that, on March 10th, 1982, due to an unusual alignment of the planets in our solar system, the Earth would be imperiled by massive earthquakes and tidal waves. Needless to say, this didn’t happen. Years later, Gribbin would say of the book, “I don’t like it, and I’m sorry I ever had anything to do with it.” The Mothman Prophesies, a 1975 work of nonfiction written by John A. Keel, argued that a large winged alien creature called Mothman caused the catastrophic December 1967 collapse of the Silver Bridge, which spanned the Ohio River. The disaster claimed the lives of 46 rush-hour commuters. In 2002, Richard Gere and Laura Linney starred in a film version of Keel’s book.

Ernest J. Gaines was one of the few writers at the time who found he was uncomfortable profiting from the confusion over fact and fiction. When his book The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman was published in the same year as Go Ask Alice, many readers assumed it was another true story. In an attempt to clarify the matter, Gaines issued the following statement: “Some people have asked me whether or not The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman is fiction or nonfiction. It is fiction. When Dial Press first sent it out, they did not put ‘a novel’ on the galleys or on the dustjacket, so a lot of people had the feeling that it could have been real.”

III.

In 1980, the New York Times’ book critic Michiko Kakutani wrote a thoughtful essay about the willingness of writers and journalists to mix fact and fiction, which touched on the work of celebrated authors like Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Tom Wolfe, John Updike, Kate Millet, and William Styron. Novelists who often lived “relatively hermetic lives,” she observed, were tempted to mine historical topics for stories once they’d exhausted their own meagre life experiences. Journalists, meanwhile, hoped to enliven their writing by employing narrative techniques more often found in fiction. But some journalists, Kakutani wrote, began “to take imaginative liberties not only with style but with the facts themselves, going so far as to attribute unverifiable thoughts and dialogue to their characters.”

These experiments in “faction,” Kakutani admits, were of varying quality. The Executioner’s Song, Norman Mailer’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning epic about the life and execution of murderer Gary Gilmore, was based on over 100 interviews conducted by the author and elicited a rave review from Joan Didion in the New York Times. Nevertheless, the problem, Irving Howe told Kakutani, is that such books “evade the responsibilities of both genres. The responsibility of fiction—to create an imaginary world with its own traits, and the responsibility of history—to be verifiable.” Furthermore, writers were often unable to resist the temptation to manipulate the facts so they could be pressed into the service of a moralistic sermon.

Consider what Judith Rossner’s bestselling 1975 novel Looking For Mr. Goodbar did to poor Roseann Quinn. Quinn was a 28-year-old New York City schoolteacher who specialized in teaching deaf children. She was murdered on New Year’s Day 1973 by a man named John Wayne Wilson whom she had met at a bar and brought home to her apartment. Humiliated by his inability to achieve an erection, Wilson stabbed Quinn 18 times. Rossner turned this ugly crime into a cautionary tale, in which Quinn became a highly promiscuous thrill seeker named Theresa Dunn, in much the same way that Sparks turned lovelorn teenager Alden Barrett into a Satanist for Jay’s Journal. Two years after the publication of Mr. Goodbar, journalist Lacey Fosburgh published Closing Time: The True Story of the “Looking For Mr. Goodbar” Murder, which further smudged the distinction between fact and fiction. Fosburgh, Kakutani reports, “allowed that she had ‘created scenes or dialog I think it reasonable and fair to assume could have taken place, perhaps even did.’”

Second-wave feminist Kate Millett went even further in her 1979 book, The Basement: Meditations on a Human Sacrifice. Her book was ostensibly the true story of the torture and murder of 16-year-old Sylvia Likens by Gertrude Baniszewski and her children in 1965. But Millett filled Likens’s head with what Kakutani calls “pages of feminist monologue.” Defending Simon and Schuster’s decision to call the book “nonfiction,” editor Michael Korda protested that, “Kate Millett didn’t invent this character. All she has done is take the facts and fill them out—make them come alive by imagination.” Interestingly, Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist and novelist John Hersey appears in Kakutani’s piece as a critic of writers who do this sort of thing. “[W]riters of nonfiction have no choice,” he tells her, “they cannot invent things. When that happens, we lose our grip on reality.” But Hersey was a compulsive plagiarist, who stole much of his book Men on Bataan from Time magazine reporter Melville Jacoby and his wife Annalee Whitmore Fadiman. A profile of James Agee that Hersey wrote for the New Yorker was largely lifted from Laurence Bergreen’s biography.

Unmentioned in Kakutani’s essay is novelist Wallace Stegner, who came into possession of a large trove of letters during the 1960s that had been written by a pioneer woman named Mary Hallock Foote (1847–1938). Stegner asked for the family’s permission to write a book based on those letters, which they granted. At first, they thought he was planning to write about the real Mary Hallock Foote, but when Stegner explained he was writing a novel, the family say he assured them that none of Foote’s actual words would appear in the book. This was important to them because, if Stegner wouldn’t do it, they planned to find someone else who could shape Foote’s correspondence into a sort of epistolary autobiography. When Stegner’s novel, Angle of Repose, was finally published, Foote’s descendants were dismayed to discover that extensive excerpts from her letters appeared on 61 of the novel’s pages.

Stegner essentially did to the heirs of Mary Hallock Foote what Beatrice Sparks would later do to the parents of Alden Barrett: he distorted a dead relative’s journals in a work of fiction that would bring great acclaim and financial rewards to its author, but not to the surviving relatives. Angle of Repose was published in 1971, the same year as Go Ask Alice, and Stegner received a Pulitzer Prize for his efforts. Today, he is regarded as one of the greatest novelists to come out of the American West. He was born eight years before Sparks and, like her, he spent much of his youth among the Mormons in Utah (although he was a Presbyterian). And like Alex Haley, Hunter S. Thompson, and many of the other fraudsters who rose to prominence in the 1970s, his offenses have now been largely forgiven, if not entirely forgotten. Neither of the Pulitzers awarded to Stegner and Haley has ever been rescinded.

All of which makes the idea that Beatrice Sparks was uniquely villainous feel faintly unfair. “Every journalist,” wrote New Yorker essayist Janet Malcolm, “who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. … He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people's vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.” This is essentially what Beatrice Sparks did to the people who trusted her, too. But she didn’t have the kind of education that Stegner and some of the other authors mentioned in this essay enjoyed—an education that might have allowed her to produce legitimate books about teenage suicide instead of exploitative confections. And despite her literary success, she never won a Pulitzer and was never even recognized as the author of her books in her own lifetime.

Nor was Sparks the only person responsible for her fraudulent work, and Emerson does a good job of pointing out just how culpable her publishers were. Editors were always having to clean up wonky timelines and other inconsistencies in her “diaries,” which ought to have tipped them off to how phony they were. Sometimes, a teenage diarist would refer to a film that wasn’t released until a year or two after their suicide (facts like these were admittedly harder for an author to check before the advent of the Internet). “Sparks was a walking correction,” Emerson writes. “When she talked about the dead girl, dates and details shifted, almost at random. Alice died in May, but sometimes November. Alice gave Sparks the diary, except when her parents did it. Sparks occasionally mentioned ‘interview tapes’ she’d made with Alice, but nobody ever heard them.”

What’s more, when her publishers copyrighted Sparks’s work, they identified her as the sole author and asserted that her books contained no pre-existing material. Nonetheless, they told readers and reviewers that the diaries were authentic. The whole deception could have been avoided if Prentice Hall had simply insisted on publishing the book as a novel written by Beatrice Sparks. There’s no reason to think she would have objected to that suggestion. But Prentice Hall also published Jane Roberts, one of the era’s most successful and prolific fraudsters, which tends to confirm the suspicion that they weren’t terribly interested in what was true and what wasn’t. Roberts claimed to have used a Ouija board and ESP to communicate with a disembodied personality named Seth. Seth dictated numerous books’ worth of New Age wisdom to Roberts from the astral plane, with which she then filled about a dozen books. Sensing the fortune to be made from this claptrap, Prentice Hall swept up the rights to all of Roberts’s Seth materials in the 1970s. They later published The World View of Paul Cezanne: A Psychic Interpretation by Roberts, to which Seth contributed an introduction.

In addition to being a fraud, Sparks is accused by Emerson of playing a major role in igniting the so-called “Satanic panic” of the 1980s and ’90s, which devastated lives, ruined reputations, and destroyed the careers of many innocent people. Here, he is on shakier ground. Sparks clearly contributed to the panic with Jay’s Journal, but she was just one of many who did so, and her role strikes me as relatively minor. Sybil, a nonfiction book by Flora Rheta Schreiber published in 1973, also became a massive bestseller and popularized “repressed memory syndrome,” the largely discredited theory that people, especially children, often suppress memories of trauma that must be drawn out of them during psychotherapy. This technique was used repeatedly during the Satanic panic to accuse parents, teachers, daycare staff, and other adults of historical instances of abuse coaxed from young accusers by a mental-health expert years later. It led to numerous false criminal convictions, many of which would later be overturned. Emerson mentions Sybil just once.

The roots of the Satanic panic can be traced to the 1960s at least. One of the earliest public faces of Satanism in America was Anton Szandor LaVey. A San Franciscan (and a minor character in Pat Montandon's aforementioned memoir, The Intruders), LaVey founded the Church of Satan in 1966 and was a very visible spokesperson for all things Satanic throughout the 1960s and ’70s, frequently appearing on mainstream talk shows. His books—The Satanic Bible, The Satanic Rituals, and so on—could be found in bookstores across the country in consumer-friendly Avon paperback editions. As a child, I remember feeling creeped out every time I saw him on television. Emerson mentions him briefly and describes him as “campy” and “a show tune-loving atheist who believed in neither gods nor devils.” LaVey’s Church of Satan, Emerson tells us, “existed mainly to tweak straight society.”

All of which may be true, but Emerson leaves out the fact that LaVey was very good at tweaking straight society, particularly white middle-class parents worried about the values their children were absorbing from TV and books. It’s easy for a hip young contemporary journalist to look back on LaVey’s career and see a campy show-tune-singing fraud. But that’s not how most Americans perceived him when they watched him on Donahue or The Tonight Show in the 1970s. In a 2001 paper for the Marburg Journal of Religion, sociologist James R. Lewis concluded that:

LaVey was directly responsible for the genesis of Satanism as a serious religious (as opposed to a purely literary) movement. Furthermore, however one might criticize and depreciate it, The Satanic Bible is still the single most influential document shaping the contemporary Satanist movement. Whether Anton LaVey was a religious virtuoso or a misanthropic huckster, and whether The Satanic Bible was an inspired document or a poorly edited plagiarism, the influence of LaVey and his “bible” was and is pervasive.

Furthermore, William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel The Exorcist (which the author claimed was inspired by an actual event) predated the publication of Jay’s Journal by more than seven years, and was followed within two years by William Friedkin’s phenomenally successful film adaptation starring Ellen Burstyn, Max von Sydow, and Lee J. Cobb. Along with the Tate-LaBianca murders and LaVey’s antics, Blatty’s book and Friedkin’s film had already mainstreamed anxieties about Satanism by the time Sparks’s book appeared in 1979. By the 1980s, Oprah Winfrey, the New York Times, and other trusted American institutions were on board with the notion that Satanism was coming for America’s children. In 1988, notes Emerson, Oprah hosted a Satanic-panic fraudster named Lauren Stratford (real name: Laurel Rose Willson) and allowed her to tell millions of viewers her fake stories of evil ritualistic abuse, including a story about how, as Oprah put it, “Her own child was used in a human sacrifice ritual.” Only in passing does Emerson note that many of Stratford’s accusations were “lifted from Sybil.”

Emerson does an excellent job of summarizing the moral panic that swept America, but he failed to convince me that Beatrice Sparks and her diaries were anything more than a single brick in a vast wall of dishonest claims. (He also tries to hold Sparks responsible for a related moral panic about the fantasy role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons, but as this account makes clear, Rona Jaffe’s 1981 book Mazes and Monsters and Patricia Pulling’s high-profile media campaign were far more important to that particular scare.) Emerson’s subtitle—“LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries”—ends up promising more than it can deliver. The most notorious diaries of the era Emerson writes about were the so-called Hitler Diaries, purchased for millions of dollars and published in Germany in the early 1980s. The hoax became a global sensation that Emerson was probably too young to remember, and were deemed authentic by the eminent historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. Forged diaries purportedly written by Benito Mussolini also caused a stir back in the 1950s. And, of course, the autobiography of Howard Hughes, also a sort of fraudulent diary, was a huge story in the 1970s. All of these strike me as more notorious than Beatrice Sparks’s work. Even Emerson notes that, “outside of Mormon circles, Sparks is basically unknown.”

Sparks’s Mormonism was not incidental to her writing career. As the money rolled in, she purchased a bookcase once owned by the Mormon prophet Brigham Young upon which she shelved her own titles, creating a direct connection between her work and her faith. She and her husband also owned a first edition of The Book of Mormon. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was founded in 1830 by a man named Joseph Smith, who wrote a book that he claimed was translated from golden plates given to him by an angel. The angel then took the plates back, leaving only Smith’s handwritten translation and his solemn word that they had actually existed. While most Mormons believe The Book of Mormon to be a true record of actual historical occurrences, almost nobody else does. It may be that Sparks simply decided that what worked for Joseph Smith would work for her too. Whenever anyone questioned the authenticity of her work, Emerson writes, “Sparks’s strategy was always the same. Admit nothing. Stick to the script. Stay on message: It’s all completely true.” She may not have gained quite as many devoted followers as Smith but, on the other hand, she wasn’t murdered at the age of 39 by a mob of angry gunmen while awaiting trial for treason.

Emerson’s book is gripping and thoroughly researched. I didn’t spot a factual inaccuracy within its 365 pages. But his narrow focus on Sparks at the expense of other culprits lacks a proper understanding of the cynical literary environment in which his subject and her publishers were operating. The entire decade’s nonfiction output was a grab-bag of pseudo-scientists, pseudo-diarists, pseudo-journalists, pseudo-historians, and pseudo-memoirists. It’s not as if no one in 1971 entertained doubts about the authenticity of Go Ask Alice; it’s just that at a time when mixing fact with exploitative fiction was widespread in publishing and journalism, the practice wasn’t considered particularly scandalous. In an otherwise glowing review of Go Ask Alice for the New York Times, book critic Webster Schott pointedly enclosed the word “diary” in quotation marks. Some reviewers avoided that problem by simply referring to the book as a novel. Others split the difference and referred to it as a “documentary novel.”

In the world of publishing during the 1970s, the line between truth and fiction simply wasn’t as clear, nor frankly as important, as it is now, so long as uncertainty shifted units. And it is only possible to shift units if there is a receptive market. It may simply be that many of the readers who devoured these books were happy to be misled—that there was something perversely seductive and even reassuring in an era of political unrest, corruption, and social upheaval about an America awash with malevolent terrors. They wanted to believe the harrowing memoirs, the ludicrous pseudoscience of the paranormal, and the fantastical stories of demonic possession, and so they didn’t care to look too closely at the clues right under their noses.

For all his criticisms, Emerson does acknowledge that Go Ask Alice has been a life-changing book for countless readers through the years. He includes endorsements from its prominent fans, such as award-winning YA novelist Laurie Halse Anderson, who has said that reading it helped her deal with her own experience as a teenage rape victim. During her childhood in Pittsburgh, actress Gillian Jacobs saw a lot of people wrecking their lives with substance abuse, and she credits Go Ask Alice with steering her away from that kind of life. Browse the reviews at Amazon and Goodreads and you’ll find hundreds of readers who say the book had a profound and positive influence on their lives. I’ve worked in bookstores on and off for much of my adult life. During that time I’ve listened to numerous customers sing the praises of some life-changing book that I found silly—The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho, The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran. Among the books that literary snobs sneer at but ordinary readers find inspiring, few seem to have improved more lives than Go Ask Alice.