Art and Culture

High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism—A Review

A review of High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism by David S. Wills. Beatdom Books, 555 pages. (November 2021)

I.

In High White Notes, his riveting new biography of Hunter S. Thompson, journalist David S. Wills describes Thompson as America’s first rock star reporter and compares him to Mick Jagger. But by the time I finished the book, I'd decided that Thompson bore a closer resemblance to Donald Trump. The two men were born nine years apart, during white American masculinity’s golden age. Both were obsessed with politics without possessing anything that could be described as a coherent political philosophy. Both men longed for some mythical American paradise of the past. Both men screwed over multiple friends and business partners. Both men would have gone broke if not for the frequent intervention of helpful patrons. Both men were egomaniacs fond of self-mythologizing and loath to share a spotlight with anyone. Both men enjoyed making disparaging remarks about women, minorities, the disabled, and other disadvantaged people. Both men were frequently disloyal to their most loyal aiders and abetters. Thompson’s endless letter writing and self-pitying 3am telephone calls to friends and colleagues were the 20th century equivalent of Trump’s late-night Twitter tantrums. Both men generally exaggerated their successes and blamed their failures on others. Both men mistreated their wives. Both men nursed a constant (and not entirely irrational) sense of grievance against perceived enemies in the government and the media. Both men had a colossal sense of entitlement…

The list could go on and on. Trump actually fares better than Thompson by various measures. For instance, Trump has never had a drug or alcohol problem, as far as I know. Thompson was a drug and alcohol problem. The first US president in living memory without a White House pet seems to have no interest in animals. Thompson enjoyed tormenting them. Rumors have circulated since 2015 that a recording exists of Trump using a racial slur but since the evidence has never surfaced, it might be fairer to conclude (at least provisionally) that this is not one of his many character failings. Thompson’s published and (especially) unpublished writings are full of such language.

All of which may lead you to conclude that High White Notes is not a favorable account of Hunter S. Thompson’s life and work. To the contrary, David S. Wills is a Thompson devotee who considers his subject to have been a great writer and, at times, a great journalist. But Wills is an honest guide, so his endlessly entertaining biography manages to be both a fan’s celebration and unsparing in its criticism of Thompson and his work.

Though impressive, the book is not without faults. Wills relies too heavily on cliché (“This book will pull no punches”; “breathing down his neck for the final manuscript”; “women threw themselves at him” etc.), and has a tendency to find profundity in unnaturally strained readings of Thompson’s prose. For instance, Wills describes a scene from a 1970 profile Thompson wrote of French skier Jean-Claude Killy, in which three young boys approach Thompson and ask if he is Killy. Thompson tells them that he is, then holds up his pipe and says, “I’m just sitting here smoking marijuana. This is what makes me ski so fast.” This sounds to me like standard Thompson misbehavior, but Wills infers something more complex: “On the surface, it appears to be comedy for the sake of comedy but in fact it is a comment on the nature of celebrity and in particular Killy’s empty figurehead status.” And when Thompson describes Killy as resembling “a teenage bank clerk with a foolproof embezzlement scheme,” Wills remarks, “Thompson has succeeded mightily not just in conveying [Killy’s] appearance but in hinting at his personality. He has placed an image in the head of his reader that will stick there permanently. It was something F. Scott Fitzgerald achieved, albeit in more words, when he had Nick Carraway describe Jay Gatsby’s smile.” (The book, by the way, takes its title from Fitzgerald, who used the phrase to describe short passages of writing so beautiful that they stand out from the larger work of which they are a part.)

Wills also overstates Thompson's originality. Thompson finds Killy hard to pin down in a profile, so he writes around his subject instead, commenting on the effect that Killy has on those in his orbit. Wills calls this an unconventional approach, but it was actually old hat by 1970. Gay Talese’s 1966 story for Esquire, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” employed roughly the same technique and is still regarded as one of the finest pieces of magazine journalism ever written. After the assassination of John F. Kennedy (a seminal event in Thompson’s life), New York newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin wrote about the man who had dug the President’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery. By the time Thompson embraced so-called New Journalism, men like Talese, Breslin, and Tom Wolfe had been practicing it for years.

Thompson, of course, hated sharing the spotlight with anyone, so he invented what he called “Gonzo Journalism.” This involved attending major cultural events while drunk and stoned, and then writing about himself while ignoring what made the event newsworthy. Wills defines it as a “fusion of fact and fiction, totally subjective, dripping with vitriol, peppered with violence and wisdom and obscene or obscure words, with its manic narrator at the center of a quest for any sort of story…”

Gonzo journalism got its start in 1970 when Scanlan’s Monthly magazine sent Thompson back to his hometown of Louisville to cover the Kentucky Derby. Thompson decided to use the opportunity to mock Louisville’s upper crust—the movers and shakers who had looked askance at people like him throughout his youth. For the assignment he was paired with a young British artist named Ralph Steadman. The two men had entirely different temperaments (Steadman was a sober and reliable professional who worked diligently and turned in his assignments on time), but Steadman’s grotesque and hallucinogenic art complemented Thompson’s wild flights of literary fantasy. Neither man was interested in documentary-style realism.

When the Derby was over, Scanlan’s flew Thompson and Steadman to New York and put them up in a hotel to complete their work. Steadman filed his in just two days. Thompson, on the other hand, couldn’t seem to get a handle on the material he had gathered, so he popped pills and drank alcohol instead and awaited inspiration. When a messenger from Scanlan’s arrived demanding copy, a desperate Thompson tore pages out of his notebook and handed them over, hoping to buy some time. These pages were relayed to Scanlan’s San Francisco office where editor Warren Hinckle and his staff set about shaping them into a coherent article. In order to make the local gentry look bad, Thompson had fed them a lie, telling them that he had come to cover the Derby because he got a tip that a race war was likely to break out there. This, naturally, upset the people he interviewed and they responded with various extreme comments of their own. Of course, it’s impossible to know how much of Thompson’s Kentucky Derby essay is true and how much of it he made up. With a narrator as unreliable as Thompson, it’s safest to be skeptical of everything he writes.

Before the story was published, Thompson was sure it would be a failure. He told an acquaintance, “It’s a shitty article, a classic of irresponsible journalism.” Be that as it may, when it appeared in Scanlan’s, “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” was a hit. William Kennedy, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and Thompson’s longtime friend, believed that the success of the Kentucky Derby essay provided Hunter with an epiphany. “I think that was a moment where he used all his fictional talent to describe and anatomize those characters and just make it all up. I’m sure some of it was real.” This would serve as a template for pretty much all of Thompson’s best-known work.

II.

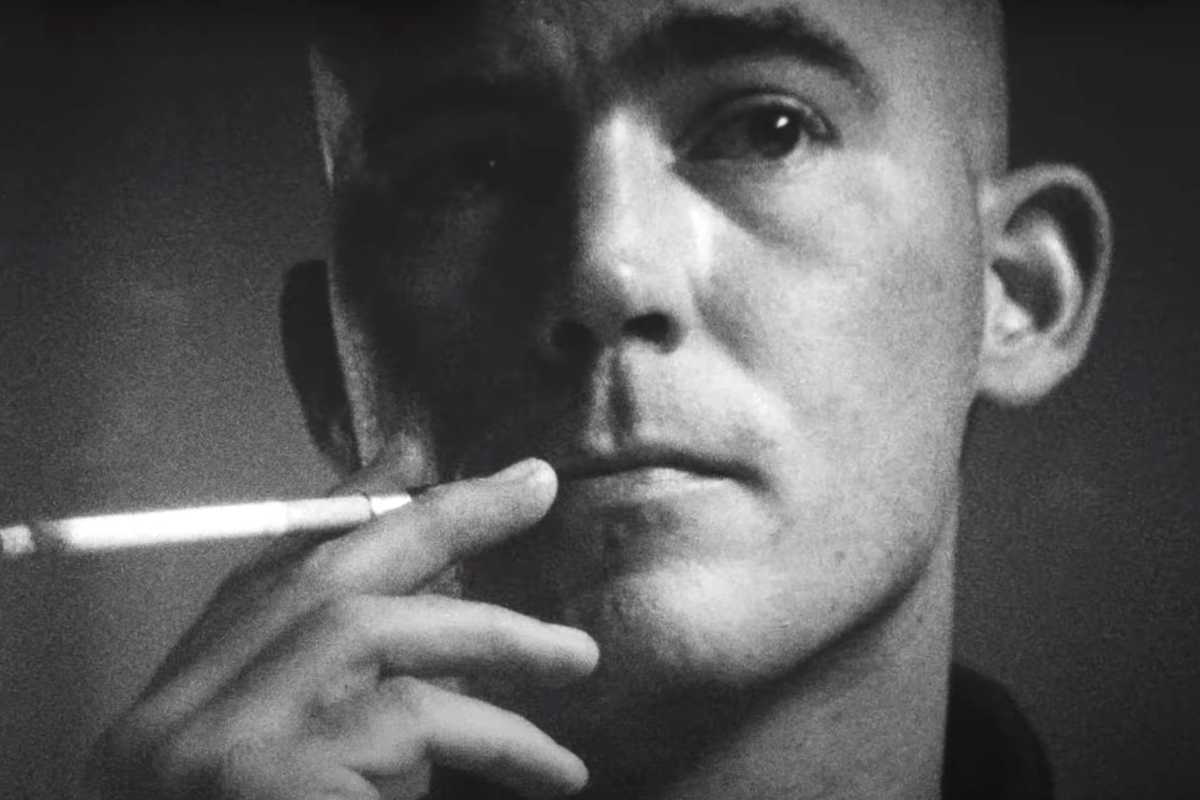

Thompson was born in Louisville on July 18th, 1937. From an early age he demonstrated the type of behavior that would be a hallmark of his adult life. He lied, he bullied, and he stirred up trouble that others often ended up paying for. According to Wills:

Violence and chaos were … parts of his life from a young age … Friends recall him often turning to violence but seldom being caught because of his charm and loquacity … He also enjoyed staging battles in the nearby woods, throwing rocks at other children, and attempting to start race wars. He would gather up his friends, rouse them into a frenzy, and then shoot BB guns and shout racial epithets at the local African American children … For Hunter, the greatest form of entertainment was doing something shocking and watching people’s reactions to it. It was even better if he could convince someone else to take all the risk while he just looked on … He enjoyed breaking things, hurting people, and using his language to assault the ideas expressed by those around him.

A childhood friend of Thompson’s recalled, “Lying was the thing he did best. He did it with total cool and total confidence.” Substance abuse was another lifelong trait he acquired early. According to Wills, “His friends have commented that Thompson began drinking whiskey at around thirteen and that by the age of sixteen he was quite possibly an alcoholic, able to drink prodigiously without ever appearing drunk.”

Thompson was 14 when his father died. His mother, Virginia, supported him and his two brothers by working as a librarian, and instilled in Thompson a love of reading and writing. When he was 17, he was charged as an accessory to a robbery and sentenced to 60 days in jail. The evidence against him was sketchy, but he was well known to the judge, who had let a previous charge slide. It seems the judge sent him to jail to try to scare him straight. It didn’t really work. After serving 31 days, he was released from prison, whereupon he joined the Air Force. He spent most of his military hitch at Eglin Air Force Base, in the far north-west corner of Florida, where he distinguished himself as a wildly entertaining but not always reliable sports reporter on the base newspaper. His rebellious behavior didn’t go down well with his superiors, and they were happy to give him an honorable discharge after three years of service.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Thompson bounced around from one newspaper to another, usually quitting in order to avoid getting fired after just a few weeks or months of employment. What he really wanted to do was write fiction, like his heroes F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. He wrote two novels during this period, Prince Jellyfish and The Rum Diary, but couldn’t find a publisher for either. He made the acquaintance of William Kennedy while working as a reporter for a short-lived sports publication in Puerto Rico, and spent a year in South America writing articles for the National Observer, a weekly newspaper put out by the publisher of the Wall Street Journal. At first, his articles for the Observer were wildly popular with both his editors and the publication’s readers. The problems began when he wrote about watching a wealthy British colonial driving golf balls off a penthouse terrace in Cali, Columbia, onto the heads of the impoverished people in the slum below. As Wills notes, “It seems a little too perfect and his editors wondered whether or not he had just invented the scene in order to present the image of a detestable colonial type, illustrating exactly what it was that many Latin Americans hated about the white man. Throughout the rest of his story, he quotes various people that also seem to say things that were extremely convenient … These sources are more like crudely drawn characters than actual people…”

This obvious falsehood, writes Wills:

…did not sit well with the Observer editors … [T]hey claimed that many of his articles now had a “fairy-story aura” and that he was “unreliable” as a reporter. When [editor] Clifford Ridley found that Thompson had quoted the Bible but gotten the wrong verse, Thompson replied, “Well, hell, one verse or another.” In his own mind, such details were not of any significance to the story he was trying to tell … In an article about Butte, Montana, more serious accusations emerged … When it was discovered that he had also made up information about the town’s population and the number of employees at the factories he wrote about, the editors confronted him. All he had to say was, “Who cares about these kinds of facts?”

Thompson eventually lost his job with the Observer. When he returned to the United States, he married his longtime girlfriend Sandy Conklin, which was good for him, though not so good for Sandy:

Throughout most of their relationship, she devoted herself to supporting his literary aspirations, keeping people away from him and making sure that he was fed so that he could spend as much time as possible at his typewriter. When he was sleeping during the morning and afternoon, she would drive all the way to San Francisco for temp work to pay their bills.

For her kindness, Sandy received little in return. According to Wills:

Hunter was always possessive and aggressive with Sandy and showed a shocking propensity for jealousy. He wrote her petulant, abusive letters demanding her total loyalty to him and would become hysterical if she talked too long with another man. Now that they were living together, he had become physically abusive toward her. She was a loving, supportive peacenik and he was a frustrated brute with little to no control over his temper. Even in that less progressive era, his behavior toward her appalled friends and visitors.

Several times Hunter and Sandy were forced to suddenly relocate because his behavior (usually involving the unlawful discharge of firearms) got them evicted from several rental homes. Their happiest times were spent living together in Big Sur, California, but those didn’t last. “Both Hunter and Sandy had loved their year at Big Sur but, after being evicted, they were unable to find a new place to stay. That was a challenge for the struggling writer and his girlfriend, particularly because the writer had spent his meager earnings on guns and Dobermans, with much of the other income having funded several Tijuana abortions.”

Thompson’s big break as a writer came in 1965 when he was hired to write an article about the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang for the Nation. The piece was so popular that Thompson found himself besieged by publishers who wanted him to expand it into a full-length nonfiction book. The Thompsons moved into the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco and Thompson set about writing Hell’s Angels, the 1967 book that would make him famous. Even in that first book, written before he had fully formulated the concept of Gonzo journalism, Thompson was already tinkering with the truth and engaging in the kind of self-mythologizing that would become a hallmark of his work. And that didn’t sit well with the Hell’s Angels themselves. According to Sonny Barger, a founding member of the Angels, Thompson “would talk himself up that he was a tough guy, when he wasn’t. When anything happened, he would run and hide.” Barger’s assessment of the book was terse: “It was junk.”

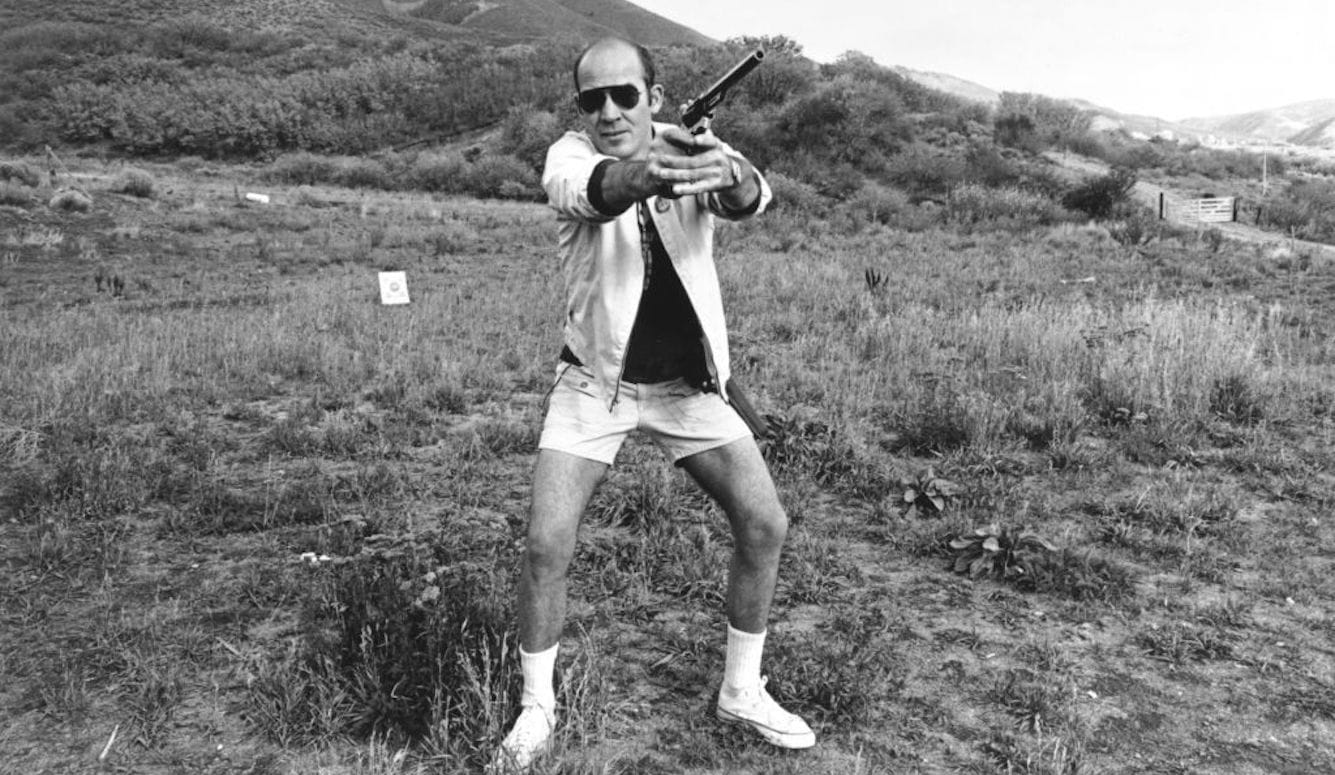

Wills notes that Thompson “tended to write about himself in ways that built his legend … to prove his machismo on paper. The back cover [of Hell’s Angels] describes him as ‘America’s most brazen and ballsy journalist’ and in the book he tells the story of first meeting the Angels and trying to impress them by shooting out the windows of his own San Francisco home. Such moments of bravado tend to enter the story very briefly and seem to serve little purpose beyond this self-mythologizing.”

But it was exactly this kind of self-mythologizing—the bragging about his drug use and general misbehavior—that editors of American magazines found so exciting about Thompson’s work, so it’s no wonder that he engaged in so much of it. It was his wild man persona that made Warren Hinckle of Scanlan’s Monthly want to unleash him among the socialites of Louisville. Still, Thompson didn’t fully emerge as a countercultural hero until he began to write for a small start-up publication in San Francisco called Rolling Stone.

III.

Founded in November 1967 by music critic Ralph J. Gleason and 21-year-old publishing industry wunderkind Jann Wenner, Rolling Stone magazine became the most important voice in America on matters regarding sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll—i.e., '60s and '70s leftwing youth culture. Playboy magazine was targeted at successful businessmen, the real-life counterparts of Mad Men’s Don Draper. But Rolling Stone was targeted at Sally Draper and her hippie, free-loving, dope-smoking friends.

At first glance, it doesn’t seem like a good match. Rolling Stone was written primarily for baby boomers like Jann Wenner—young people, mostly born after the Second World War, who had been raised on television and rock music. Thompson was born in the 1930s, had served in the military, loved handguns, and was fond of throwing around casually racist and misogynistic comments. His work was almost completely devoid of references to sex and rock and roll. He developed a fondness for Bob Dylan, Jefferson Airplane, and other favorites of the Woodstock Generation but he wasn’t raised on rock music and didn’t seem terribly interested in writing about it. Worse, he had written an article for New York Times Magazine in 1967 in which he had criticized the hippies and compared them unfavorably to the Beatniks who preceded them. Nonetheless, Jann Wenner, with almost preternatural insight, saw that Thompson’s anarchic, anti-authority vibe would be popular with Rolling Stone’s readers, who were fond of anything that rebelled against The Establishment.

Thompson’s first story for Rolling Stone, “The Battle of Aspen,” was published in October 1970, and recounted his quixotic campaign to become Sheriff of that Colorado community by harnessing what he called “Freak Power,” an effort to turn “Flower Power”—a sort of amorphous message of peace and love embraced by America’s hippies—into a legitimate political force. His next piece, “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” was an investigation into the murder of Chicano activist and journalist Ruben Salazar by officers of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. It was published in April of 1971. Even in those early days of his affiliation with Rolling Stone, Thompson missed deadlines and needed plenty of help completing his stories. Wills writes of the finished piece, “It must be noted here that this was not all Thompson’s work. He was mostly producing short bursts of writing from different parts of the story and sending them for his editors to piece together.”

Those first few pieces for Rolling Stone attracted plenty of attention, but it was his next assignment that would establish him in the public mind. While researching the piece on Ruben Salazar, Thompson relied heavily on the assistance of Oscar Zeta Acosta, a Mexican-American attorney who was active in the Chicano Power movement. But many of LA’s more militant Chicanos didn’t like seeing Acosta so closely aligned with a white journalist, and wanted nothing to do with the “gabacho pig writer.” To escape the attention, Thompson suggested that Acosta accompany him on a brief trip to Las Vegas. Sports Illustrated had offered to pay him to write captions to accompany photographs of a motorcycle race set to take place in late March of 1971.

If matching Steadman with Thompson and Thompson with Wenner was serendipitous, so too was the matching of Thompson and Acosta. In many ways Acosta was more Gonzo than Thompson. He was at least as paranoid as Thompson (it was Acosta’s idea that they should rent a convertible for the trip to Las Vegas, making it harder for anyone who might have bugged the vehicle to hear their conversations). He was also more pugnacious than Thompson (he disappeared in 1974, and is believed to have been killed after mouthing off to some Mexican drug dealers in Mazatlán). And he seemed to have unlimited access to illegal drugs. So, Thompson and Acosta drove from southern California to Las Vegas, ostensibly so that Thompson could cover a motorcycle race.

As it happened, Thompson didn’t see the race (not unusual; even when acting as the sports editor of his Air Force newspaper he frequently wrote about sporting events he hadn’t actually witnessed). Sports Illustrated didn’t use the material he submitted, but Thompson didn’t care. He began writing a personal essay about his and Acosta’s drug-fueled antics in Vegas and circulating it among the top people at Rolling Stone. They liked what they saw and suggested that Thompson and Acosta return to Las Vegas for the District Attorneys’ Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs which was set for the end of April, 1971. This time Thompson came to Las Vegas prepared. He brought a portable tape recorder and, for several days, he and Acosta rambled around Vegas capturing its sounds and voices on tape. Both men spoke their observations into the microphone and conducted numerous interviews with people they encountered. They believed they were conducting research for a book about the death of the American dream.

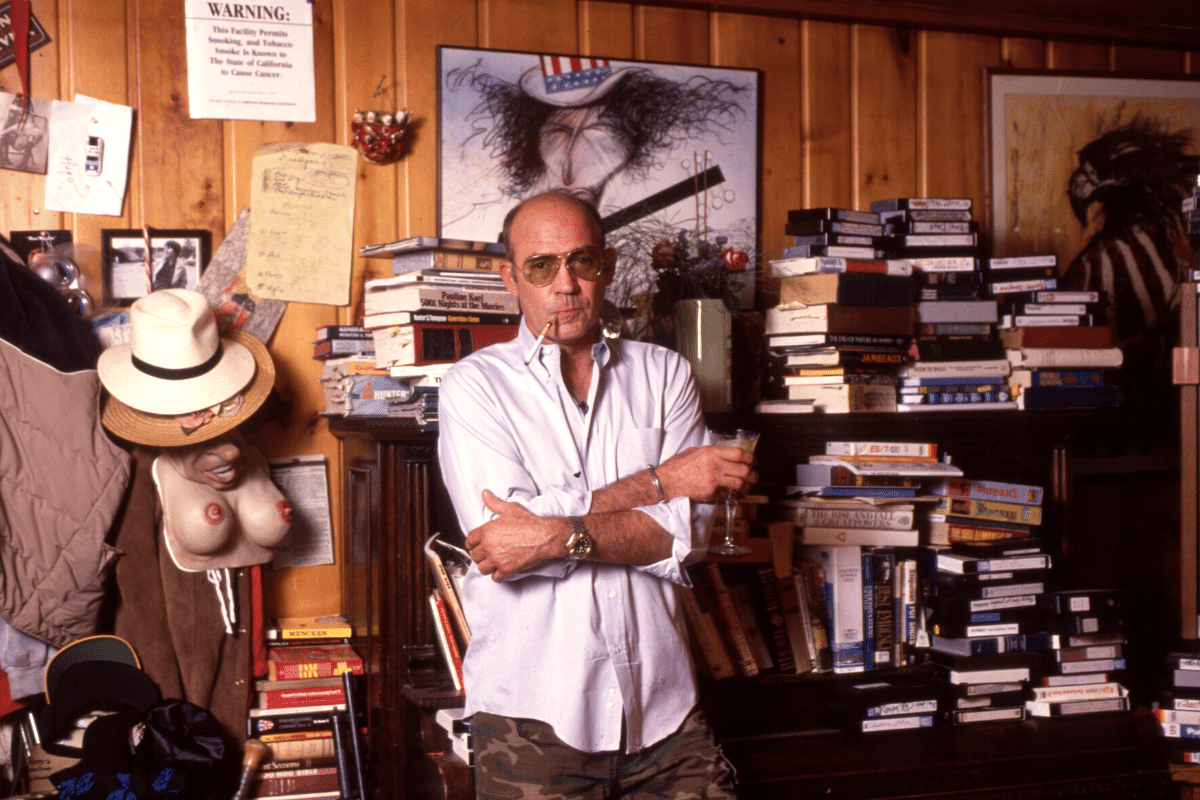

When the trip was over, Thompson repaired to Woody Creek, CO, where he and his wife and child were now living in a cabin on Owl Farm, a rural piece of land he had bought with the money he had earned from Hell’s Angels. For the next six months, fueled by Dexedrine and bourbon, Thompson spent eight to twelve hours a day typing out the adventures of Raoul Duke (his own alter ego) and Doctor Gonzo (a thinly disguised Acosta) in Sin City, USA. He called this piece “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.”

According to Wills, Thompson did his best writing when he had a sidekick character, a bit of an outsider to American culture, to whom he could act as a guide. In his Kentucky Derby piece and others, Ralph Steadman served as Thompson’s foil. In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, it is Acosta. Acosta, however, is an American, which is why Thompson disguised him as Doctor Gonzo, whom he describes as a Samoan attorney. At any rate, according to Wills, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is essentially “the tale of two men doing truly vast quantities of different mind-bending substances. There is not a scene in the book where both men are sober and clear-headed.”

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was published first as a two-part essay in back-to-back issues of Rolling Stone, on November 11th and 25th, 1971 (the magazine published every two weeks). Eight months later, the whole thing was published as a book by Random House. Like most of Thompson’s work, it is too unreliable to be treated as journalism. Even the prodigious drug consumption was invented—as Wills points out, “their fantastic pharmacopoeia never existed and any actual drug use in Las Vegas was comparatively tame.” But the lack of a plot and believable characters also make it unsatisfactory as a novel. That is, unless, like Wills, you believe that the prose by itself is brilliant enough to overcome all of the book’s other shortcomings. And this is where Wills’s book is at its strongest.

The case he makes for Thompson’s prose being the equal of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s is both compelling and downright forensic. One of the most famous parts of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is the so-called Wave Passage, which compares the rise and fall of America’s hippie movement to an actual ocean wave that swelled, crested, and crashed. Wills examines this passage on a granular level, showing how, by varying the number of syllables per line, Thompson created a passage that, when plotted out on a graph (and he includes the graph), actually describes the rise and fall of a large wave. He demonstrates how the final passage of The Great Gatsby, Thompson’s favorite book, which also deals with waves (“So we beat on, boats against the current…”), describes an almost identical wave pattern.

Thompson didn’t just read Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, he obsessed over it, practically committing it to memory and, once, actually typing the whole thing out himself, so that he could learn what it felt like to create such rhythmic and poetic sentences. Thompson knew Gatsby on a cellular level and Wills seems to know Thompson’s work as intimately. The problem—for me, at least—is that very little of Thompson’s work qualifies as among his best. And even the best of his writing is generally in the service of dubious “journalism.”

IV.

Thompson considered almost all of his work, even books like Hell’s Angels, to be critiques of America’s mainstream press, whose journalists he despised as lackeys and lapdogs of the rich and the powerful. No doubt mainstream American journalism has never come close to being free of fear or favoritism. But at the time when Thompson was heaping disgust on the American press, mainstream journalists and their editors and publishers were risking jail sentences and financial ruin by publishing the Pentagon Papers and reporting on the Watergate scandal.

Absolutely no journalist in America hated Richard Nixon as fiercely as Thompson did. Wills plausibly speculates that the end of Nixon’s career was one of the three major things that destroyed Thompson as a journalist (the other two being drug/alcohol abuse and fame). And yet, if Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post had assigned Thompson to investigate the break-in at the Watergate complex, Thompson would have gotten wasted, invented an interview with a fabricated Washington brothel operator, turned in his story several months late, and guaranteed that his bête noire remained in office until January of 1977.

Over and over again, Wills shows that Thompson was an extremely difficult person to work with. Editors, publishers, fellow writers—he repeatedly made their lives hell. Wills reports that Thompson would receive a generous advance for a freelance assignment, abuse his expense account, and then deliver no story at all, or else a story so fragmented that an entire staff of editors had to work overtime to make sense of it. This kind of behavior became routine. What’s more, writes Wills, “Thompson typically submitted his work long after the deadline had passed and there was rarely enough time for anything to be fact-checked.”

Every few pages of Wills’s book brings another example of Thompson screwing people over. Thompson always had difficulty with self-discipline, but his inability to produce any work was exacerbated by his cocaine abuse. This was certainly bad for his career. But it was also bad for the careers of those in his orbit. Steadman joined Thompson in Zaire where Rolling Stone had sent them to cover the Ali-Foreman fight. Steadman was eager to see the fight, but Thompson told him, “I didn’t come all this way to watch a couple of niggers beat the shit out of each other.” On the morning of the fight, Steadman frantically tried to find Thompson, who had their press passes, but Thompson had sold them and used the money to buy cocaine and marijuana. When Steadman finally found him, he was stoned and was throwing large quantities of marijuana into the hotel pool:

Steadman, who had tolerated his unruly roommate throughout their stay, heroically enduring the bingeing, bitching, and raging, was understandably upset. He needed to see the fight in order to do his illustrations. At this point he thought Thompson might still manage a last-minute, deadline-busting effort … But it just wasn’t going to happen … Rolling Stone, having paid more than twenty-five thousand dollars in expenses and fees for the story, refused to run Steadman’s illustrations, which they considered too dark to print without Thompson’s writing.

When the US military began pulling out of Vietnam, Wenner asked Thompson to cover it for Rolling Stone. Thompson agreed but began to lose his nerve as his departure date drew near. Wenner asked New York Times war correspondent Gloria Emerson to try to bolster Thompson’s confidence. The phone calls between them were recorded (Thompson—like Nixon—recorded many of his phone calls and conversations), and Emerson can be heard telling him how to cover the story, passing him the details of her own contacts and translators, and offering to provide him with all the facts about Vietnam that he lacked.

Thompson finally arrived in Vietnam in April of 1975 (more than a decade after the mainstream journalists he hated began covering the story on a daily basis). He took a lot of opium, mingled with prostitutes, and generally behaved like a clown in order to entertain the other journalists, many of whom were fans of his work. But, as Wills remarks, his behavior “wasn’t as funny in real life.” The other journalists quickly realized that his antics might get him—and them—killed. At least 60 Western journalists were killed covering the war and, as Wills points out, “few of them were running around high on drugs.” Tape recordings make it clear that he was hopelessly out of his element. The other journalists can be heard laughing at his ignorance of the facts on the ground. They teased him about the fact that he hadn’t managed to write a word about the Ali-Foreman fight when Norman Mailer had managed to write a groundbreaking piece for Playboy.

Later, by himself, Thompson can be heard spitting out the words, “Fuck them!” on the recorder. At one point, stoned out of his mind and believing he was chasing “four giant fucker pterodactyls,” Thompson wandered dangerously close to the front line. Several journalists had to put themselves in harm’s way to bundle him into a jeep and drive him back to relative safety. Five days after he arrived, he retreated to the safety of Hong Kong. He later claimed that he did this in order to secure some money and drugs for his journalist friends in Vietnam, but Wills points out that this was another lie. Audio recordings show that he left Vietnam because he was afraid. Thompson eventually returned to Saigon, but only because he got the idea he might later be able to pass himself off as the last American journalist to leave Vietnam. Eventually he fled for the relative safety of Laos. According to Wills, Thompson wrote very little about Vietnam. Most of Rolling Stone’s coverage of the fall of Saigon came from Laura Palmer, their other reporter in Vietnam. Without her, they would have missed out on one of the biggest stories of the decade.

V.

With each passing year, Thompson became less and less reliable. Wills writes: “When Thompson was offered fifteen thousand dollars by Esquire to cover the [Mariel] boatlift he took the money and ran up a further fifteen thousand dollars of expenses. Unsurprisingly, he did not bother to write anything.” Another serious story involving all kinds of human tragedy, and yet, while those “pig-fuckers” of the mainstream press brought much of that tragedy into the living-rooms and newspapers of Middle America, Thompson took the money and ran (to the nearest cocaine dealer).

When Jann Wenner decided to expand his empire into film production, he asked Thompson to write a screenplay. Thompson relied heavily on a young collaborator named Tom Corcoran, who knew more about the technical details of film than Thompson did. Corcoran wrote most of the screenplay, entitled Cigarette Key, which Wenner managed to sell to Paramount (who never produced it). Thompson squandered all of the screenwriting fee without sharing any of it with Corcoran.

Thompson's Colorado neighbor, Don Henley, co-founder and drummer of the Eagles, asked him to write an essay about environmentalism for a project whose proceeds were supposed to help save Henry David Thoreau’s famous Walden Pond. But Thompson couldn’t muster the energy, so instead he turned in a personal essay about torturing a fox (trapping it, spraying it with mace, gluing feathers onto its fur, shooting buckshot at it, etc.) that he had published previously and which Henley and his partners couldn’t use. (Animal torture was a game Thompson loved to play; he used to torture his pet mynah bird, record the animal’s distressed cries on tape, and then play them back to appalled listeners, laughing while they squirmed in discomfort).

In 1994, Rolling Stone hired Thompson to write a two-part story about the US Polo Open. Only one part of the story was written because Thompson had run up expenses of $40,000 by that time and the magazine couldn’t afford to eat any more of these costs. In the year 2021, many talented young college-educated journalists don’t earn $40,000 for a year’s worth of freelance work! According to the career-research website zippia.com, even American journalists who have full-time employment earn an average of only $52,000 a year. Adjusted for inflation, the $40,000 in expenses that Thompson ran up on one story back in 1994 would be $73,332.25! Over the course of his career, Thompson probably earned more money (adjusted for inflation) for work he never turned in than most contemporary journalists will earn in their lifetimes for work they actually do. Throw in the money he bilked from expense accounts and most journalists will never come close to earning as much.

To help him with his story on polo, Thompson was assigned a young Rolling Stone editorial assistant named Tobias Perse. According to Wills:

[Perse] suffered through Thompson’s rages for months and was repaid by Hunter’s inclusion of him in the story as a simple-minded creep. Perse recalls that it could have been worse: “He had been writing me into the Polo story as a character, and that character went from being kind of fierce—beating people with golf clubs and that sort of thing—to being introduced like this: ‘The magazine sent me an assistant, a tall, jittery young man. He said, “My name is Tobias but my friends call me Queerbait.”’ Over four months, I cut Queerbait every time I sent it back to him, and every time he’d change it back. I finally had it cut in the copy department just before we closed the issue.”

Homophobia was one of Thompson’s many unpleasant traits. Wills again: “Hunter was never entirely comfortable with the idea of homosexuality … he often appeared homophobic. After his brother came out to him, Hunter refused to discuss it. When Jim Thompson was dying of AIDS in 1994, it was Sandy—by then a decade and a half divorced from Hunter—who looked after him and begged Hunter to visit.” Of that divorce, Wills writes:

After nearly two decades of abuse, Thompson’s long-suffering wife picked up and left him in 1980. The police had to come and escort her from the property as Hunter threatened her and threw all of her writing into a fire. He was distraught, but the sadness soon turned to pettiness and he had a new reason not to write—he did not want Sandy to get her hands on any more of his money.

A few years later, Thompson was covering the divorce trial of Roxanne Pulitzer and her wealthy older husband Herbert “Peter” Pulitzer, and complained about the unfair treatment of women in American divorce proceedings. Wills notes, “One can hardly fail to note the irony in Thompson’s criticisms, though. He had done everything in his power to limit Sandy’s claims to their shared property and wealth during his own divorce trial.”

VI.

There always seems to be something inherently phony in people whose shtick is authenticity—as if the effort to play themselves becomes too much to bear. Hunter S. Thompson, Spalding Gray, Anthony Bourdain, even to some extent Robin Williams—these guys all specialized in solo performances of their own public personae. Wills repeatedly refers to Gonzo journalism as “a one-man genre.” A book about monologist Spalding Gray is called Cast of One. Williams was a manic one-man stand-up comic. Bourdain was best known for being the only regular cast member in a string of reality food programs in which, as he put it, “I travel around the world, eat a lot of shit, and basically do whatever the fuck I want.” That kind of freedom, the freedom to just be yourself, probably feels at first like the perfect gig until it doesn’t. There’s only one sure way to escape a role like the ones they were playing, and in the end they all chose it.

But finding yourself stuck in a seat next to Spalding Gray or Anthony Bourdain during a long plane flight might have been interesting. Those guys could at least do humility and interest in other people (sometimes the interest even seemed genuine). But being stuck in a seat next to Hunter S. Thompson during a long airplane flight sounds like a good reason to request an urgent reassignment.

Thompson was a world-class hater. Unless you were a celebrity like John Belushi or Dan Aykroyd who he was trying to suck up to, he’d probably have made you miserable. According to Wills he could be violently angry with anyone in the service industry, screaming “Punk!” “Asshole!” and “Loser” at waiters and hotel staff, and once got into a fistfight with a restaurant chef whose lasagna he considered inedible. You don’t have to take Wills’s word for it. Thompson amply demonstrates his contempt for common people in his books—in the first few pages of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, we find him complaining that “we had to stand in line with all the others.”

In spite of all this terrible behavior—the entitlement, the egocentricity, the cruelty, the endless wasting of other people’s time, money, and patience—the glamorous myth of the fearless and righteous outlaw journalist persists. To this myth, Wills’s fascinating biography offers limited endorsement, but also a valuable and comprehensive corrective. We are left in no doubt that the man whose work Wills admires was, by nature, a colossal jerk—alcohol and drugs only aggravated the problem. If there’s a hell, Thompson is probably sitting in it right now. Handcuffed to Richard Nixon.