Top Stories

Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb—A Review

Freak Power is a fascinating look into the heart of a grassroots political campaign during a violent era in American history, as one man channelled the rage and confusion of a maligned subculture into a surprisingly coherent and subversive political movement.

Fifty years ago, in a small mountain town in Colorado, a young writer led a band of misfits against the establishment in a grassroots political movement they called “Freak Power.” That writer was Hunter S. Thompson, author of Hell’s Angels and creator of Gonzo Journalism. His revolutionary campaign would capture the attention of the nation and influence local politics for decades to come. These improbable events are the subject of a new, independently produced documentary comprising recently uncovered archival footage.

In 1970, Thompson was just a year away from writing Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and fast becoming a name in the world of American journalism. While researching Hell’s Angels, he had embedded with the notorious biker gang and rode with them until they inevitably turned on him and issued a savage beating. Although he dismissed the Angels as “losers,” he recognised that their violent image provided them some measure of power in a society that was otherwise tipped against them: “In a prosperous democracy that is also a society of winners and losers, any man without an equalizer or at least the illusion of one is by definition underprivileged.”

Thompson, of course, had his own “equalizer”: His burgeoning literary talent became a weapon against those he viewed as corrupt, particularly after his 1968 experiences on the streets of Chicago, where Mayor Daley’s thuggish police force launched a violent attack on protestors and press alike. As Thompson later explained: “I went to the Democratic Convention as a journalist, and returned a raving beast.” His journalism morphed into something entirely original, laced with vitriolic scorn and dripping in sarcasm—henceforth, the writer would be at the forefront of the story, outrageous and bold, like a Hemingway for the hippie era.

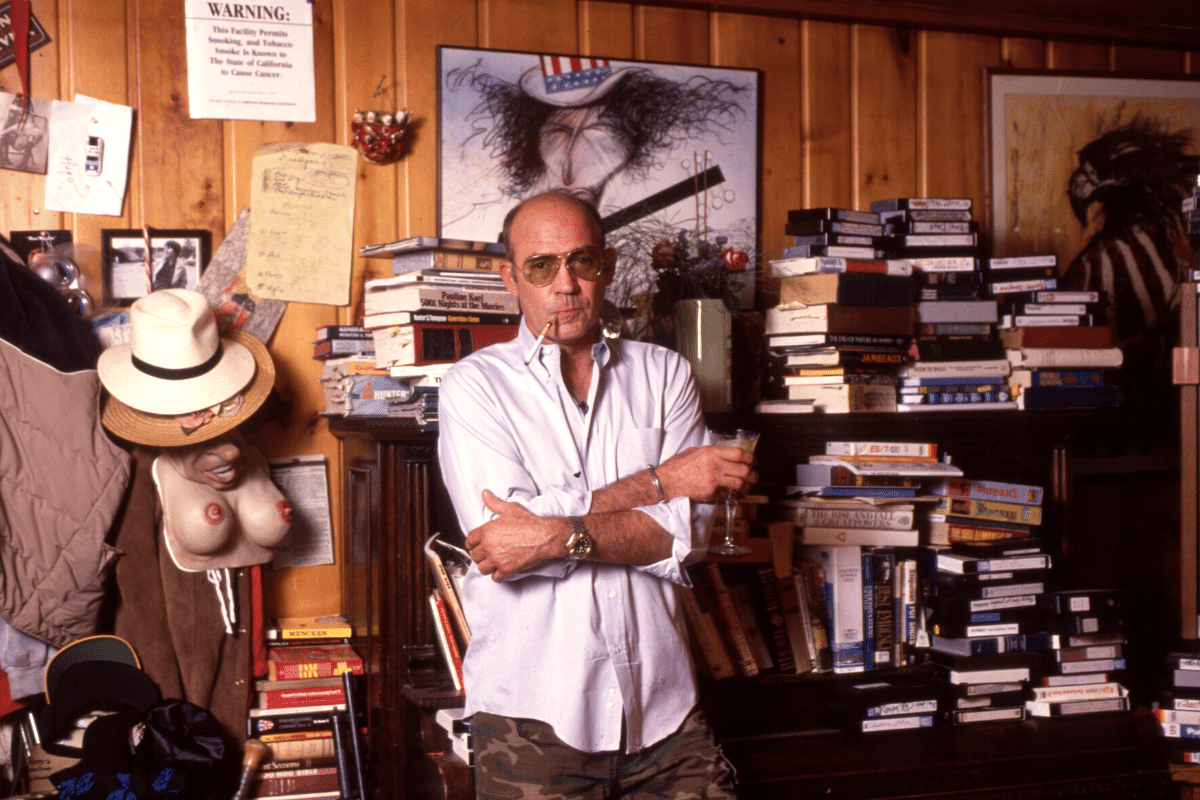

Since childhood, Thompson had been a ringleader, a troublemaker, and an incorrigible prankster. It was perhaps inevitable, then, that he would do more than just document the lives of outlaws. He set about becoming one, even moving to his own so-called “fortified compound” in the small town of Woody Creek, just outside of Aspen, Colorado. Here, he found his own piece of paradise but soon found its beauty and way of life under attack from rabid land-developers. Moreover, there was an ugly undercurrent in the town. The local government included several former Nazis who had emigrated to the US after the war, and it was openly and violently persecuting the young hippies and artists who had moved there to escape the Draconian drug laws of cities like San Francisco. Thompson decided he would not stand for it. He made his position clear in several satirical letters to the local press, but between 1969 and 1970 he resolved to step outside the role of journalist and into the realm of politics and law enforcement. Hunter S. Thompson, an open user of various narcotics, was about to run for sheriff.

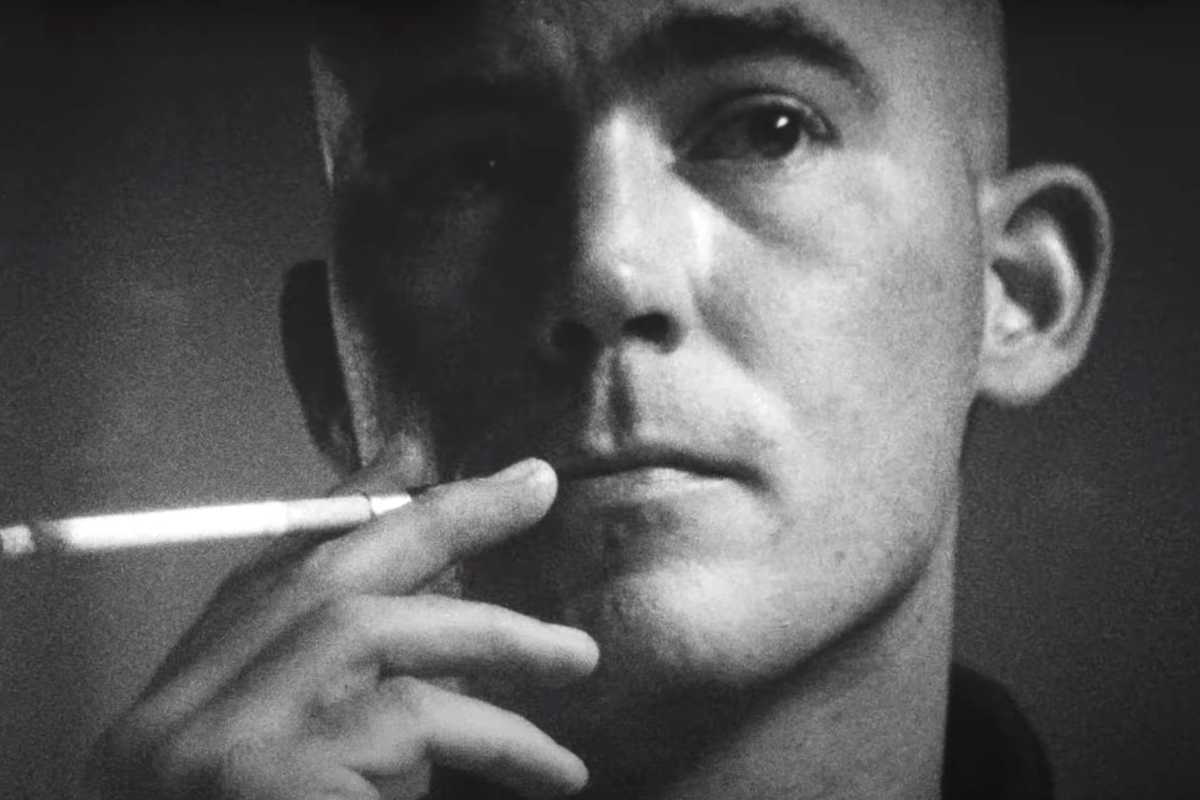

This campaign provides the basis of Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb, a new film by D.J. Watkins and Ajax Phillips. Utilising archival footage uncovered over the last three years, they have deftly woven the provocative narrative of Thompson’s election campaign into an entertaining and timely documentary. We encounter intimate footage of Thompson and his campaign staff preparing their bizarre crusade against the incumbent sheriff, Carrol Whitmire, whose police force was notorious for its violent suppression of civil rights. There is also a wealth of film showing the two candidates debating. Thompson had shaved his head and referred to the incumbent (who wore a crew-cut) as “my long-haired opponent.” And for all the mischief and tomfoolery, he comes across remarkably well. Though he labelled himself a freak and thrived on a vituperative vocabulary, he made for a compelling public speaker; intense and ferociously intelligent. His quick wit—delivered in staccato bursts of his trademark mumblese—made short work of Whitmire, who mostly sat dumbfounded as the audience laughed along to Thompson’s caustic jabs.

Watkins and Phillips have done a superb job of capturing the ins-and-outs of the Freak Power campaign and the turbulent era that made it possible. Their use of photos and video from the 60s—including footage from Kent State and the Chicago Democratic Convention—shows a divided country that looked for a while as if it might disintegrate entirely. Film of local Aspenites Guido Meyer and Eve Homeyer show the irrational, prejudiced attitudes of an entrenched power structure that stood against the unkempt youths flocking to the town’s snowy streets. This was a cultural clash that took national issues and brought them to the heart of small-town USA. Thompson, who had never shown any political aspirations, was nonetheless willing to spearhead what he saw as an important movement with ramifications that could lead to national change. “I’m not sure I want to be sheriff,” he admits in the film, “but it seems as though the whole concept of democracy rests upon somebody doing what has to be done.”

Images of violence and anger set against the clash of conservative and liberal values will be uncomfortably familiar to viewers in this most peculiar of years. But regardless of political standpoint, Thompson’s campaign is inspiring: In the face of voter intimidation, death threats, and the concerted efforts of various law enforcement agencies, he marshalled a coherent political movement that masqueraded as a joke whilst propagating positive and provocative messages. He used his greatest asset—satire—to unite a disparate group of potential voters and lampoon the comically regressive and frequently hypocritical attitudes of his opponents. As with his literature, the distinction between sincerity and irony was not always clear, but in his witty platform we find an earnest desire for environmental protection and a more inclusive community, with power wrenched from the handful of wealthy landowners who had jealously guarded it for too long.

Despite his portrayal in the mainstream media of the era, Thompson was no hippie. He felt an affinity for their music, their drug choices, and their Jeffersonian ideals, but his own politics were more complex. Though this film overlooks those complexities—no doubt to appeal more directly to those who stand in opposition to power today—Thompson’s views were radically unique. He was not a flag-burner, but a patriot who revered the US Constitution. And he was no pacifist, but a libertarian and firearms enthusiast, vehemently opposed to any infringement of individual rights or the abuse of power by authorities, elected or otherwise. By playing up the role of king-freak, he aimed to draw attention away from more qualified candidates, allowing them to slip surreptitiously into power as the media fixated upon the mescaline-munching candidate for sheriff. However, as it became clear he had a chance of winning, he began to prepare for the possibility.

Thompson’s campaign drew upon the same ideals as his journalism. On the surface, it appeared to be simply provocative and outrageous; underneath, however, lay a surprisingly common-sensical approach to local governance. He claimed that he would rename Aspen “Fat City” to deter would-be land developers; that he’d disarm the police and equip them instead with trained wolverines; and that he’d publicly punish dishonest drug dealers—nonsense policies that nevertheless reflected his concern with environmental conservation, responsible policing, and the protection of civil liberties. He aimed to re-define the role of sheriff as an ombudsman overseeing a compassionate police force that fostered and maintained a peaceful society that welcomed outsiders while protecting the interests of locals.

Thompson succeeded in registering more than 800 new voters and appealing to a surprisingly wide cross-section of the Aspen electorate. Nevertheless, it was not a great surprise that he ultimately lost the election—his campaign’s outrageousness had inspired a bi-partisan effort that defeated him. However, the Freak Power message ultimately succeeded as subsequent sheriffs, including local legend Bob Braudis—who is extensively interviewed in this film—adopted much of Thompson’s campaign platform. The Battle for Aspen had been lost, but the War was ultimately won.

For those already familiar with the story of Thompson’s run for sheriff, Freak Power provides a good deal of previously unseen material. The archival footage of the writer is masterfully cut with scenes of Aspen’s hippie sub-culture, the ad campaigns used by both sides, and interviews with various Freak Power campaign staff and others, including Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner and Thompson’s Gonzo partner-in-crime, Ralph Steadman. Watkins’s collection of Freak Power posters is used to demonstrate the artistic brilliance of Tom Benton, with whom Thompson published an innovative journalistic hybrid called the Aspen Wallposter. The extensive use of home footage brings both Aspen and the campaign to life in a way that no book or article has yet managed.

The result is a visually satisfying documentary that offers an intimate insider’s view of a well-known event. The film of Thompson’s concession speech, shot on a hand-held camera within the crowded campaign headquarters, is particularly affecting. Wrapped in an American flag and sporting a gray permed wig, Thompson declares, “Unfortunately, I proved what I set out to prove… that the American Dream really is fucked.” This quote is already well-known for its inclusion in the BBC documentary, Fear and Loathing in Gonzovision. However, the full speech allows viewers to appreciate its intelligence as well as the hope placed in him by his disappointed young followers.

Freak Power is a fascinating look into the heart of a grassroots political campaign during a violent era in American history, as one man channelled the rage and confusion of a maligned subculture into a surprisingly coherent and subversive political movement. It was a rallying call for the triumph of democracy over violence; an inspiration for intelligence, creativity, and civil debate over cheap tactics like voter intimidation and street violence. Fifty years have elapsed since these events occurred, but this documentary is as important and timely as ever.