Books

Barney Rosset and the Unending Struggle to Read Freely

It is by now a familiar truism that the Internet—and social media, in particular—has awarded the intolerant, the narrow-minded, and the censorious unprecedented power. To this challenge from below, publishers have, by and large, responded with dismaying timidity. Large multinational publishing firms have hastily withdrawn controversial titles and it has become distressingly common to read apologies issued to those vilifying their authors from the blogosphere, along with undertakings to “listen” and “do better” in the future.

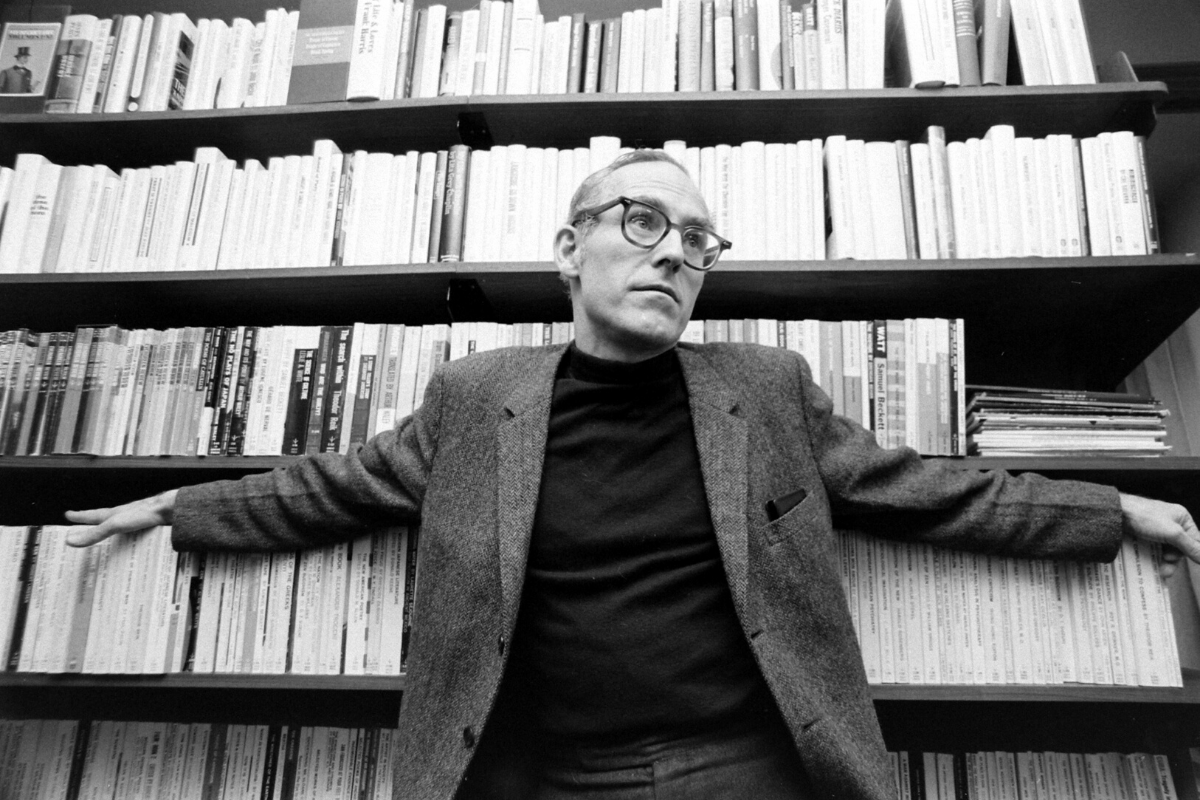

With these regrettable circumstances in mind, it is worth recalling the life, career, and example of renegade American publisher Barney Rosset. During the 1950s and 1960s, Rosset turned a tiny publishing company named Grove Press into one of America’s most provocative and effective instruments of free expression. He published some of the most controversial books of the 20th century and he never apologized for anything. In 1968, his offices were firebombed by anti-Castro Cuban reserve officers in the American Air Force because he had published excerpts from Che Guevara’s diaries in Grove’s magazine, the Evergreen Review. The same year, Valerie Solanas, founder and sole member of SCUM (the Society for Cutting Up Men), stalked Rosset outside Grove’s offices hoping to stab him with an ice pick when he left the building to go to lunch. When he failed to emerge, she gave up and decided to shoot Andy Warhol instead.

Then, during a foray into the film-distribution business in 1969, Rosset purchased the US distribution rights to Swedish director Vilgot Sjöman’s 1967 softcore film I Am Curious (Yellow). This turned out to be the most profitable investment Grove Press ever made, but it enraged radical feminists, two dozen of whom occupied Grove’s offices sporting buttons that read “We Are Furious (Yellow).” According to Michael Rosenthal, author of the Rosset biography Barney, they were angered by Grove’s “exploitation of women as evident in the pornography it published.”

But Rosset didn’t care about protestors or their slogans. He cared about film and literature—he was as passionate about the freedom to read and watch what one wanted as he was about the freedom to write, publish, and exhibit it. And in defense of these freedoms, he went out of his way to pick fights with anyone who disagreed. He usually won, too. The fortunate beneficiaries of those victories are you, me, and anyone else who doesn’t like having their reading material chosen for them in a free society.

I

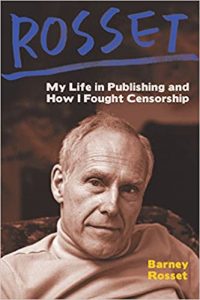

Barney Rosset was born in Chicago on May 28th, 1922. His mother was an Irish-American Catholic and his father was an irreligious Jew. According to his posthumously published autobiography, Rosset: My Life in Publishing and How I Fought Censorship, he came from a long line of troublemakers. The book opens with this declaration:

"Rebellion runs in my family’s blood. We have never shown a willingness to accept unthinkingly what authorities told us was right or wrong, in good taste or bad. The repression of imposed conformity has always been something we fought against no matter what the odds."

Rosset goes on to tell the story of his great-grandfather, an Irish peasant named Michael Tansey, who was sentenced to death for murder. Wealthy British landowners controlled much of Ireland’s soil at the time, and they refused to let the natives fish or hunt on their estates. Tansey, like many other Irishmen back then, was forced to poach fish and game in order to feed his family. When he was eventually caught by the landlord’s estate manager, Tansey killed him. A jury found him guilty and sentenced him to hang, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment after a petition for clemency reached the court. He was released when he was an old man and died a few years later. Rosset concludes the story of Michael Tansey by noting, “His family—and therefore mine—had formed part of the clandestine revolutionary movement in Ireland, which eventually ousted their English overlords from much of the country. It is a heritage of which I am very proud.”

Rosset, it must be said, was no Michael Tansey. His father, Barney Sr., had made a fortune in the banking business and so his son was born into wealth and privilege. Although the family suffered losses during the Depression, they were spared true hardship. Barney Sr. was a Republican, a capitalist, and a supporter of Herbert Hoover, but his son was nonetheless educated almost entirely in very progressive grade schools and high schools. This was probably due to the influence of his mother, a liberal Democrat, and he developed an early admiration and affinity for rebels, misfits, and outlaws. One of his childhood heroes was the American gangster and serial bank robber John Dillinger. At his first school, Rosset organized a petition not only demanding that Dillinger be pardoned, but that he replace Herbert Hoover as president. “We need people like that at this time in our history!” the petition declared.

When the Gateway School was shuttered due to lack of funds, Rosset was enrolled at Francis W. Parker, which he described as “a private school, heavily subsidized by a woman who was a liberal aristocrat.” In his memoir, he notes wryly that:

"It was at Parker that my long relationship, so to speak, with the Federal Bureau of Investigation began. In the seventh grade I read George H. Seldes’s book on Mussolini, Sawdust Caesar, which was destined to play a big role in my government files… I detested Mussolini. Seldes made it very clear that Il Duce was powerful and very dangerous. Subsequently, the FBI reported that I was a “fascist” and an admirer of Mussolini. The reason for this outright lie remains a mystery. After years of obtaining documents from my huge file through the Freedom of Information Act, I determined that I was only called a fascist while I was in grade school. They tagged me as a “radical” from high school on—“radical” was much more to their taste."

On this last point, the FBI wasn’t entirely wrong. Rosset was a radical. In the eighth grade he and a friend began publishing their own school newspaper called the Sommunist, a word they coined by combining Socialist and Communist. Later they changed its name to the Anti-Everything.

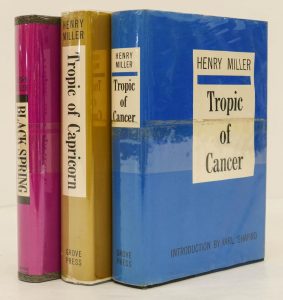

After high school, Rosset attended several colleges but didn’t manage to obtain a degree at any of them. It was during his first (and only) year at Swarthmore, in 1940, that he discovered the works of Henry Miller. On the advice of a friend, Rosset traveled to New York to buy a copy of Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, which was banned in the US, from the Gotham Book Mart. He read the book and wrote a paper about it for a class. “I never found Miller’s novel especially sexy,” he admitted in his autobiography. “But it was exciting (if also depressing) because it was so truly and beautifully anti-conformist. My paper for class was titled ‘Henry Miller Versus “Our Way of Life,”’ and it discussed whether the American way of life was worth defending, and concluded, reluctantly, that it was.”

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Rosset briefly enlisted in the infantry, and found himself stationed at a training camp in Oregon with a bunch of poor and working-class soldiers who were almost certain to be killed or injured in ground combat in Europe or the Pacific at some point. Rosset’s worried father persuaded his son to let him pull some strings and so Rosset spent much of the war in China instead, shooting footage of the fighting against Japan. The experience left him with a lifelong love of movies and filmmaking that would eventually have a profound and consequential effect on the direction in which he took Grove Press.

When the war ended, Rosset married abstract expressionist painter Joan Mitchell, and the couple settled in Greenwich Village where they became part of the thriving postwar New York art-and-literature scene, hanging out with the likes of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Surrounded by artists and writers, Rosset struggled for a while to find something useful to do. He tried unsuccessfully to get a job with the United Nations before returning to college and finally earning a BA from the New School of Social Research. By this time, however, his marriage was dissolving and he and Joan would divorce in 1952. They remained friends, however, and even as the marriage faltered, Joan “in a rather beautiful final act” went to Barney with her artist friend Francine Felsenthal, and encouraged him to enter the world of publishing.

A friend of Felsenthal’s named John Balcomb had established a tiny company named Grove Press after the West Village street where he lived, but had run out of money after publishing only three books, all of which were reprints of works first published before 1900. So, in December 1951, Rosset (with financial help from his father) bought an interest in the company for $1,500 and became Balcomb’s partner. Shortly thereafter, he bought out Balcomb as well, and began transforming Grove Press from an inconsequential reprint house into America’s most daring publisher of avant-garde literature.

II

Rosset’s first important campaign in the censorship wars began in 1954 with his efforts to publish an unexpurgated edition of DH Lawrence’s erotic novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Rather than try to sneak it into bookstores before the government could stop him, Rosset printed the novel and then asked an associate in Paris to mail copies of it back to him. Importing banned materials was a violation of US Customs regulations and Rosset sent several letters to the relevant New York authorities informing them he was expecting a shipment of books then deemed pornographic. He hoped the shipment would be intercepted and confiscated, thereby providing the grounds for a lawsuit. Instead, his warnings were simply ignored.

So, he had another copy mailed to him from Paris. This time, however, when it arrived he took it down to the customs office himself and turned himself in. Perplexed New York customs officials remained reluctant to take any action and sent the book on to the ominous-sounding Government Collector of Restricted Merchandise in Washington, D.C. There, whichever bureaucrat was given the responsibility of reviewing the book determined that it was indeed contraband and impounded it. This finally provided Rosset with the fight he had been looking for, and he immediately sued the US Postal Service for violating his First Amendment rights.

This was a calculated move, but it was a risky one, nonetheless. Two years earlier, New York editor and publisher Samuel Roth had been convicted of sending his supposedly obscene quarterly American Aphrodite through the US mail. Roth was fined $5,000 and sentenced to five years in prison (of which he served four). Rosset lost the first round in court, as he expected, but he was gambling that the Federal Appellate Court would reverse the lower court’s finding. On July 21st, 1959, Judge Frederick van Pelt Bryan overturned the original decision, ruling that Lady Chatterley’s Lover was not obscene and that it was therefore entitled to First Amendment protection. In his opinion, Bryan wrote:

"It is essential to the maintenance of a free society that the severest restrictions be placed upon restraints which may tend to prevent the dissemination of ideas. It matters not whether such ideas be expressed in political pamphlets or works of political, economic, or social theory or criticism, or through artistic media. All such expressions must be freely available."

It was a magnificent victory and a huge relief. Rosset had spent nearly $100,000 pursuing the case, which was roughly the equivalent of a million dollars today. Had he failed, Grove would almost certainly have been shuttered and Rosset could plausibly have been thrown into jail. The costs were borne entirely by Rosset and Grove Press and he was never compensated for them.

Curiously, Rosset wasn’t even all that bothered about DH Lawrence’s novel. It was merely a stalking horse—a tactical ruse used to mask Rosset’s ulterior purpose, which was to be the first person to publish Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in America. But Tropic of Cancer was filthier than Lady Chatterley’s Lover by several orders of magnitude—it contained more graphic depictions of sex and more obscenities than Lawrence had ever dared try and fit into a single novel. Rosset had worried that if he’d used Tropic of Cancer as the subject of his first censorship battle, he might lose badly in court. Miller was a living American writer with little in the way of mainstream acceptance. Lawrence, on the other hand, had been dead for nearly three decades by the time Rosset took up his cause. He was therefore safely ensconced in the English literary canon which made it comparatively easy to find scholars and writers willing to defend his work. Miller, however, would be a much harder sell in an American courtroom.

Nevertheless, emboldened by his victory with Chatterley, Rosset set about trying to publish Tropic of Cancer. This was never going to be easy. Even Henry Miller wasn’t especially enthusiastic about the prospect of a confrontation with the law. He kind of liked the cultural caché that came with being a literary miscreant whose books couldn’t be published in his own country. He was also—though he would have fiercely denied it—less courageous than Rosset. Miller had no desire to risk prison or bankruptcy in some high-minded battle against censorship. But Rosset was spoiling for another fight, and this time around, he spent close to a quarter of a million dollars (more than two million contemporary dollars) defending the right of Americans to read what Miller had written. According to Michael Rosenthal:

"Barney’s commitment to defend the First Amendment regardless of the consequences then inspired him to do what no other American publisher would have had the courage—or the divine craziness—to do: underwrite all the expenses, legal and otherwise, of booksellers facing criminal charges for trying to sell the banned volume. Over the next several years, sixty separate cases in twenty-one states were brought against bookstore and newsstand owners and clerks accused of violating local obscenity ordinances. Barney organized defense teams in every instance, absorbing all the costs. His willingness to put his money where his constitutional principles lay marked him as unique in the history of American publishing."

On June 22nd, 1964, the US Supreme Court overturned the ruling of a lower court and decided that Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer was not obscene. Then, two years later, Rosset managed to get a Massachusetts appellate court to rule that William S. Burroughs’ underground classic Naked Lunch was not obscene either! Anyone who doubts the importance of these two decisions in reshaping America’s cultural landscape can look through Michael Korda’s 2001 book Making the List: A Cultural History of the American Bestseller, 1900–1999. Barney Rosset’s name does not appear in Korda’s compendium, but his influence is easy to spot.

During the first half of the 20th century, the annual bestseller lists were filled by wholesome religious parables with titles like Unleavened Bread, The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come, In the Bishop’s Carriage, The Keys of the Kingdom, and so on. Those lists also contained some bona fide classics, such as The House of Mirth, The Hound of the Baskervilles, and The Virginian, but nothing for the years 1900 through 1910 (with the possible exception of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle) was likely to have appalled the sophisticated reader in 1890. But as Norman Mailer (whose cousin, Charles Rembar, was Barney Rosset’s attorney in many of these censorship battles) noted, Rosset’s 1966 defense of Naked Lunch in particular “changed the literary history of America. It opened up the possibilities. After that, American publishers were pretty much willing to print anything.”

The bestselling novel of 1966 was Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls, a novel filled with reasonably graphic depictions of (pre-marital, extra-marital, homosexual) sex, drug abuse, and other subjects that couldn’t possibly have been dealt with so frankly in a mainstream bestseller prior to Rossett’s crusade. The second bestselling novel that year was Harold Robbins’ The Adventurers, a tale filled with candid descriptions of sex, rape, murder. Many of the best-known fiction bestsellers of the late 1960s and ‘70s could not have been published until Rosset’s courtroom victories opened the doors to more uninhibited and permissive fiction: Rosemary’s Baby, The Godfather, John Updike’s Couples, Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge, Portnoy’s Complaint, The Exorcist, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, Scruples, and so on.

It wasn’t just the fiction bestseller lists that changed, either. The list of bestselling non-fiction books for the year 1949 included not one, not two, but three different titles about canasta and not one but two different religious tomes by men named Fulton (The Greatest Story Ever Told by Fulton Oursler, and Peace of Soul by Fulton J. Sheen). The nonfiction bestseller lists of the 1970s included no books about canasta or written by men named Fulton but plenty of books about sex, such as Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask, The Sensuous Woman and The Sensuous Man, Any Woman Can!, The Joy of Sex, My Secret Garden: Women’s Sexual Fantasies, and many other titles in the same vein.

Barney Rosset helped to transform the literary landscape in America, making it safe for mainstream publishers to print and sell books containing frank depictions of sex, violence, drug abuse, alternative lifestyles, and more. Michael Rosenthal summed up the influence of the Supreme Court’s 1964 decision like this:

"Although it took several months before all legal attempts to interfere with the sales of Tropic stopped, Barney had finally succeeded, with a major assist from William Brennan [the Supreme Court Justice who wrote the opinion], in changing the rules regarding censorship in America. Unwittingly—and certainly unintentionally—Miller had led Barney to his greatest victory. Old Smut Peddler though he might have been, Barney also deserves to be recognized as the twentieth-century’s most intrepid First Amendment warrior."

III

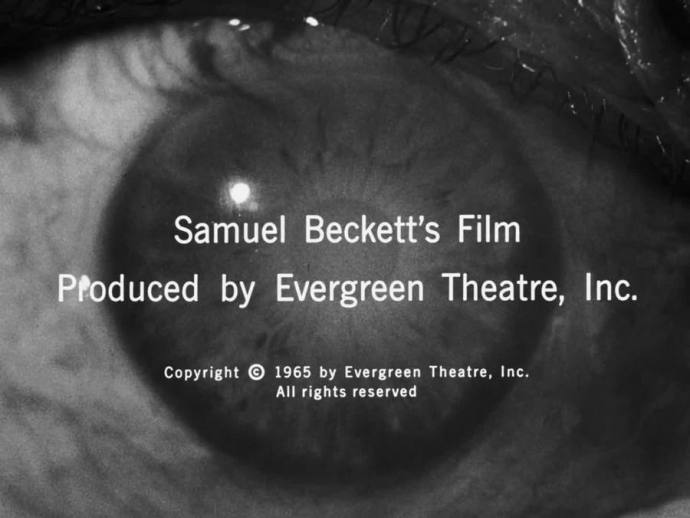

Although Barney Rosset is mainly remembered today for his work as a publisher, one of his greatest triumphs came in the field of film distribution. Rosset’s experiences with his photography unit in World War II instilled in him a lifelong desire to make a mark in cinema. “In the wake of Hollywood’s postwar decline,” he wrote in his autobiography, “there was a growing audience for films of a higher intellectual quality, more in line with the literature Grove was publishing.” So in the early 1960s, Rosset created Evergreen Theater, a cinematic spinoff of his book and magazine publishing business.

With the assistance of Jason Epstein at Random House, Grove formed a partnership with Four Star Television to produce original scripts which would be written by Grove and Evergreen Review authors. In 1963, Evergreen Theater secured screenplays from literary heavyweights Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Eugene Ionesco, Marguerite Duras, and Alain Robbe-Grillet. The idea was to produce a portmanteau film comprising the stories of all five of these writers, but—like many of Rosset’s grand ambitions—this never came to fruition. Only Beckett’s script, Film, was ever made into a movie by Evergreen Theater. Undeterred, Rosset spent much of the 1960s compiling a library of films purchased from other distributors, most of which were obscure and experimental shorts by artists like Agnes Varda, Kenneth Anger, and Michelangelo Antonioni. Most of these films had never been seen outside of a few avant-garde New York venues, and Rosset hoped to make money distributing them to theaters across America.

It was at the Frankfurt Film Festival in 1968 that Rosset first read about a controversial new Swedish film entitled I Am Curious (Yellow). He subsequently claimed that he knew instinctively that the film would be a perfect fit for Evergreen Theater, and contacted the Swedish producers to secure the US film rights for $100,000. “Though hardly explicit sex by today’s standards,” Rosset later wrote, the film “was a scandal the minute it hit this country; at the airport it was seized by US Customs officials on charges of obscenity.”

"The parallel between this and the battles I had fought over censorship in print was immediately apparent. I declared at the time that Curious might win for the film industry the same freedom afforded literature in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover case. My prediction did come true, but it took more than a year’s worth of local and federal court cases. As we had done with the legal cases for the books, we brought in notable witnesses for our defense, including Norman Mailer and film critics Stanley Kauffman, John Simon, and Hollis Alpert. The jury found the film obscene but, in an almost unprecedented move, the ruling was later reversed by the US Court of Appeals, which declared I Am Curious (Yellow) was not obscene under the Supreme Court’s definition of the term."

When the film finally opened in March of 1969, it generated huge lines at its New York premier. To get the film screened in American cities that weren’t as progressive as New York, Rosset sometimes had to resort to extreme tactics. Some theaters refused to show the film on the standard percentage basis, fearing that no one in the community would come to see it and the theater owners would be left with nothing for their troubles. So Rosset would simply rent the theater, screen the film, and then collect all the box office receipts for himself. “In Minneapolis,” he wrote, “we actually purchased a theater just to show the film and sold it when the run was over!”

I Am Curious (Yellow) earned Rosset and his company more money than any other venture in the history of Grove Press and its offshoots. Sadly, it also marked the beginning of the end for the upstart company. In the early 1970s, Grove was plagued by problems, most of which Rosset would come to blame on the FBI, which he said disapproved of Evergreen Review’s anti-Vietnam War stance and Rosset’s many and various battles with the arbiters of public decency. The company found itself beset by protests from feminists scandalized by I Am Curious (Yellow), and an enormously disruptive and damaging unionization initiative by Grove employees marked by radical agitation and sabotage.

Rosset suspected that the latter had been secretly ginned by the FBI or CIA or both, and that the union “was aiding and abetting the government effort to bring Grove down.” After all, no other publishing company was facing pressure to unionize. This campaign, Rosset later wrote, dragged him and his long-time employees through “a living hell. Every day the building was emptied out by bomb threats and fire alarms… This went on for two or three months.” By the time it was over, Grove was broke.

IV

It would be easy to dismiss Rosset’s accusations against the FBI as the paranoid rantings of a delusional businessman whose brainchild was dying. But his autobiography provides enough glimpses into his thick and detailed FBI file to support his suspicion that the government had a hand in Grove’s demise. Still, Rosset wasn’t a completely innocent party to the death of his company. After the box office triumph of I Am Curious (Yellow) (it was the 12th highest-grossing film of 1969), he bet heavily on European cinema imports, and spent a good deal of money securing the rights to numerous highbrow European films which he hoped would recreate the success he had enjoyed with Curious.

Alas, the times had finally outpaced him and this turned out to be a poor investment. The success of Curious in court had helped to make the exhibition of even more explicit cinema possible, and by the early 1970s, the golden age of porno chic arrived with Gerard Damiano’s Deep Throat (1972) and The Devil in Miss Jones (1973) and the Mitchell Brothers’ Behind the Green Door (1972). It turned out that it was not a yearning for European arthouse cinema that had sent Americans flocking to see I Am Curious (Yellow). Grove was now sliding into financial distress from which it never recovered. Pornography, radical feminists, union agitators, and the FBI had done what legions of American anti-smut crusaders had failed to do over the previous 20 years or so: drive Grove Press to the brink of extinction.

The publisher limped along until the Summer of 1979 when an unlikely savior appeared on the horizon. Shortly before Apocalypse Now was scheduled to be released, Rosset met with Francis Ford Coppola in San Francisco. Anticipating that his new film would be as financially rewarding as his Godfather pictures, Coppola offered to buy Grove Press and leave Rosset in charge of the day-to-day operations. The two men worked out an oral agreement, under which Coppola would buy up office space for Grove in San Francisco and Rosset would move the company’s operations there after closing down the New York offices. The idea was that they would finalize terms for the bailout in August, when Coppola would be in New York for Apocalypse Now‘s premier. Rosset was thrilled. Unfortunately, strange though it may now seem, Apocalypse Now was not a financial success upon its release. When Rosset met Coppola in New York, the crestfallen filmmaker told him, “You know, I’m broke, Barney. Everything I have is gone.” As Rosset remarked in his memoir, “It took years before Coppola pulled out of his financial hole. I stayed in mine.”

Though mortally wounded, Grove Press still had one last amazing literary coup to pull off. In 1980, Rosset purchased the paperback rights to an obscure hardback novel, published by Louisiana University Press and written by an unknown writer who had committed suicide in 1969. It was entitled A Confederacy of Dunces and it turned out to be a sensational hit, earning its tragic author, John Kennedy Toole, a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1981. The book sold well but its success was not enough to save its publisher. So when British publisher Lord George Weidenfeld and oil heiress Ann Getty offered in 1985 to buy Grove for $2 million and leave Rosset in charge he had no option but to accept. Barney Rosset’s 35-year run as America’s most fearlessly iconoclastic publisher finally came to an unceremonious end during a meeting in April the following year:

"When I was informed I was being thrown out, I turned to the man sitting next to me at the meeting, Marc Leland, who worked for the Gettys, and said, “I don’t get it. Am I hearing straight? I’m no longer running Grove Press?” As I remember it, he basically said, “Oh, you knew that. You knew the day you signed the contract we were going to throw you out as soon as we could.”

Eventually the new owners merged the press with the Atlantic Monthly Press. It exists today as Grove Atlantic, but it is no longer subversive or anti-establishmentarian. It is just another perfectly ordinary corporate publishing entity, indistinguishable from all the others.

V

Barney Rosset was a remarkable man who had an incalculable effect on American culture, but he was certainly no saint. Stubborn, awkward, and often difficult to get along with, his personal life in particular was a horrible mess. His first romance ended when he and his girlfriend, both 18, got in a fight and he slugged her in the jaw. At the age of 43, he divorced his second wife and married his 10-year-old son’s 18-year-old babysitter, and his countless extramarital affairs would wreck four of his five marriages. In the notes for his autobiography, he wrote of himself: “This competition for girls was a very subtle thing, taking many forms, and also being a very chauvinistic thing in that the girl was basically a prize to be sought after, not an important human being.”

Nevertheless, Rosset was a man of rare courage and principle who took great risks in the name of a freedom about which he cared deeply—the censorship battles he waged 60 years ago sought to expand the range of material available to Americans who loved all kinds of writing. In 2008, four years before his death, he received the National Book Foundation’s Literarian Award, which honors service to the American Literary Community. A dedication to Rosset at the foundation reads:

"Barney Rosset, through his publishing house, Grove Press, and his magazine, the Evergreen Review, introduced American readers to such literary giants as Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Jean Genet, and Eugène Ionesco, as well as many of the writers of the Beat generation. He fought two landmark first amendment battles in order to publish the uncensored version of DH Lawrence’s novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. Rosset was a tenacious champion for writers who were struggling to be read in America and this award recognizes his vision and his enormous contributions to American publishing."

Given his messy personal life and the fact that he was widely disparaged as a pornographer for much of his career, it seems unlikely that, were he still alive today, any reputable national organization would bestow its highest honor upon him. Which is a shame. I was born in the 1950s, so I was practically raised on the pop fiction of the next two decades on which Rosset had such a profound impact. I feel an enormous sense of gratitude for the work he did and the risks he took to make the American literary scene of my younger days so much freer and more interesting. As Judge Samuel Epstein wrote in his decision upholding Rosset’s right to publish Tropic of Cancer:

"Let the parents control the reading matter of their children; let the tastes of the readers determine what they may or may not read; let not the government or the courts dictate the reading matter of a free people.

The constitutional right to freedom of speech and press should be jealously guarded by the courts. As a corollary to the freedom of speech and press, there is also the freedom to read. The right to free utterances becomes a useless privilege when the freedom to read is restricted or denied."

Following this decision, Rosset’s lawyer Charles Rembar wrote a book about their battles called The End of Obscenity. Rosset hated the title because, according to his biographer Michael Rosenthal, “he felt society’s impulses to impinge upon creative freedom would never entirely disappear.” Sadly, it appears that he was right. And he would no doubt be appalled that, in the early 21st century, it isn’t the government and the courts that are the greatest censors of our reading material.

Many of the freedoms for which Barney Rosset fought with such dedication are being thoughtlessly squandered by those who take them for granted or who demonstrate no real understanding of their fragility or importance. Most astonishing of all, many of the new censors are themselves writers. Hachette cancelled publication of Woody Allen’s memoir Apropos of Nothing following a campaign led by Allen’s estranged son, who is a journalist, and a walkout by its own staff. The campaigns against various authors of young adult fiction have been led and joined by their peers, some of whom then found themselves targets of similar outcries. And there has been no shortage of columnists eager to publish think-pieces denouncing the authors of novels like Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt or even a feminist cookbook like Rage Baking.

Barney Rosset was an emancipator committed to opening America’s cultural horizons over the objections of those who sought to diminish them. He correctly understood that the struggle to read and write freely, even in a country as free as America, is unending. But it was a cause to which he devoted himself because he really believed in it:

"Some people think my chief claim to fame is having published the first book to be sold over the counter in this country with the word fuck printed on its pages in all its naked glory… There has been much more to my publishing career, of course, than that. I believe, more fairly, that I should be thought of as the publisher who broke the cultural barrier raised like a Berlin Wall between the public and free expression in literature, film, and drama. My determination to publish an unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterley in 1954 was consistent with my long-held conviction that an author should be free to write whatever he or she pleased, and a publisher free to publish anything. I mean anything."