Art and Culture

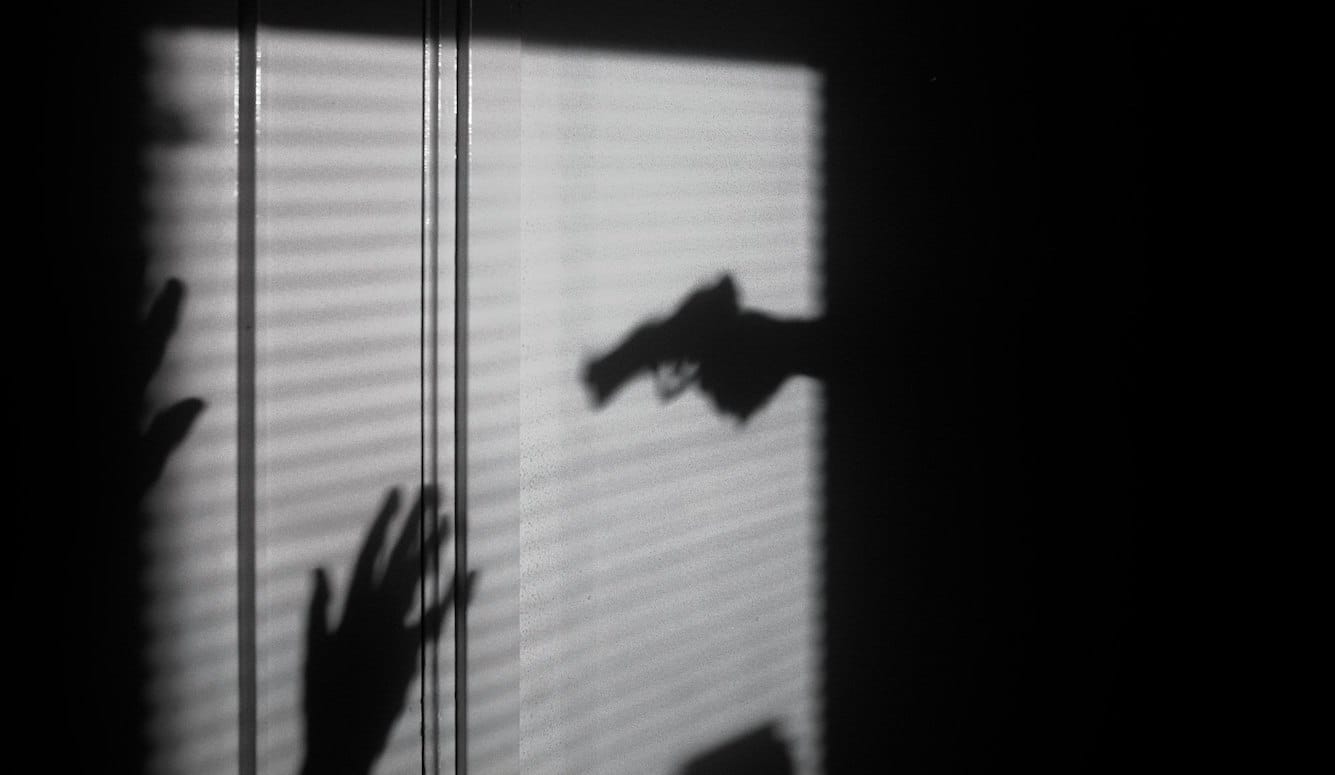

Monks and Murder

Modern literary master William Kotzwinkle returns after a lengthy absence to serve up a double Bloody Martini.

Editor’s note: This essay is followed by a bonus interview with Mr. Kotzwinkle conducted by the author.

Over the last six decades or so, William Kotzwinkle has published 20 novels, eight story collections, and 20 books for children. That tally is somewhat subjective, though, because much of his work is difficult to categorize. The novel count, for example, includes two film novelizations, a couple of graphic novels, a book-length poem, and Swimmer in the Secret Sea, which was originally published as a short story in the pages of Redbook magazine. Two of his earliest novels—his 1972 debut Hermes 3000 and his 1974’s Nightbook—read more like collections of linked stories than novels. More than half of his story collections are aimed at young readers, and could also be listed among his books for children. Then, between 1997 and 2020, this formerly prolific author went rather quiet, publishing only one book aimed at grown-up readers.

But in 2021, he published a hardboiled crime novel titled Felonious Monk, followed this month by its sequel, Bloody Martini. It has been about a quarter-century since he brought out two novels in such quick succession, but the wait has been worth it. The main character is Tommy Martini, the grandson of a prominent Mafia don, who flees to a Catholic monastery in Mexico after he kills a patron during a violent altercation at the bar where he works as a bouncer. Martini has been in the monastery for five years when he learns that his uncle, a crooked Catholic priest, is dying in Arizona and wants to see him. Martini inherits his uncle’s estate and finds himself hunted by dangerous mobsters who suspect that inheritance includes $7 million of their money. The sequel finds our hero back in his Mexican monastery. When a high-school friend is murdered, he travels to his fictional hometown of Coalville (probably somewhere in Pennsylvania, where Kotzwinkle was born) in pursuit of the culprits.

In the manner of classic pulp-fiction crime tales, Kotzwinkle keeps the chapters short, the dialog pithy, and the violence graphic. Martini is a lone-avenger archetype, brimming with pent-up rage and eager to make up for the time lost to isolation. This hardboiled fiction was a change of pace for Kotzwinkle, but crime has long been a staple of his fiction in some shape or form. The protagonist of The Fan Man is a small-time crook. Doctor Rat seems to have been inspired, in part, by Josef Mengele’s crimes against humanity. Fata Morgana (no relation of the Werner Herzog film) blends magical realism with a detective story set in 1860s Paris. The Game of Thirty mixes a contemporary crime drama with ancient Egyptian mysticism. Even some of his children’s books, such as Trouble in Bugland, about a praying mantis who solves insect-related mysteries, are full of crime.

Kotzwinkle doesn’t write about himself, however, which makes him a somewhat difficult figure to profile. But by scouring the Internet, it is possible to assemble a somewhat sketchy portrait. All the sources I checked agree that Kotzwinkle was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania (also the hometown of President Joe Biden, who was born almost exactly four years later). His father, William John Kotzwinkle, was a printer and his mother, born Madolyn Murphy, was a housewife. Like Biden, Kotzwinkle was raised in the Catholic faith.

For decades, Scranton has been synonymous with economic decline, so it seems unlikely that Kotzwinkle grew up in affluence (Biden didn’t). And Kotzwinkle credits Scranton with helping him develop an earthy sense of humor intolerant of vanity and pretension. (Curiously, writer Margot Douaihy, another Scranton native, has just begun producing a series of mystery novels featuring a crime-fighting Catholic nun, Sister Holiday, who is more punk-rock than pious bride of Christ. The first book in the series, Scorched Grace, is scheduled for release on February 21st, just a week after the release of Bloody Martini.)

Encyclopedia.com notes that Kotzwinkle was an only child who attended Rider College (now Rider University, New Jersey) and Pennsylvania State University, where he studied drama and playwriting. He dropped out of Penn State in 1957 and moved to New York to pursue a more bohemian lifestyle. There, he worked various odd jobs, including work as a department store Santa Claus during the Christmas season (an experience that lent authenticity to his 1982 novel Christmas at Fontaine’s).

In the early 1960s, he worked as a short order cook and an editor/writer at a tabloid newspaper. His hobby was playing folk music on the guitar. For a time, he studied acting until he realized that the lines he was coming up with in improv classes were much better than his acting. So, he moved from acting to writing, first plays and then fiction. His first published work was a children’s picture book called The Firemen, which was illustrated by Joe Servello, an old school friend who would go on to collaborate with Kotzwinkle on many other projects. In 1965, he married novelist Elizabeth Gundy, who seems to be even more publicity-shy than her husband. Gundy has written five novels, one of which, Bliss, was turned into a 1980 TV movie called The Seduction of Miss Leona starring Lynn Redgrave.

Membership of the Silent Generation (approximately 1930–45) places Kotzwinkle between two major American literary movements. He was born too late to be a true member of the Beat Generation, whose biggest names—Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Ferlinghetti—were mostly born in the 1920s. And he arrived too early to be a Baby Boomer, whose biggest literary stars—the Pulitzer Prize-winners Jeffrey Eugenides, Michael Chabon, Richard Russo, Michael Cunningham, Robert Olen Butler, Jane Smiley, Oscar Hijuelos, and Elizabeth Strout—mostly emerged from MFA programs at elite universities.

Kotzwinkle was among a group of writers—including Ken Kesey, Richard Brautigan, Larry McMurtry, Robert Stone, Ed McClanahan, Raymond Carver, Thomas McGuane, Cormac McCarthy, and Hunter S. Thompson—who were born in the 1930s and didn’t fit comfortably into either of the groups that bracketed them. Kotzwinkle would have been just shy of his 30th birthday during 1968’s Summer of Love. Nevertheless, his work includes elements of both Beat literature and some of the more playful work of Boomer writers such as David Foster Wallace, Michael Chabon, and Jonathan Lethem.

Chabon’s 2000 novel, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, was inspired in part by the lives and careers of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two Jewish friends who had created the Superman comic books. In 1983, Warner Books published Superman III, Kotzwinkle’s novelization of the Richard Lester film of the same name. Chabon’s book won a Pulitzer Prize, while Kotzwinkle’s paperback original was swiftly forgotten. But this is part of Kotzwinkle’s charm. Writers like Chabon and Lethem take pop culture so seriously that they often postmodernize all the fun out of it. Kotzwinkle, on the other hand, has always been happy to embrace pop culture for what it is, without having to prove to anybody that he’s better than those, say, who enjoy Superman stories unironically.

The Beat elements in Kotzwinkle’s work include references to jazz, drugs, surrealism, and outsider culture. His first novel, Hermes 3000, is named after the model of typewriter on which Kerouac wrote his final book, and it seems to have been a partial homage to Beat writing—less a novel than a rogue’s gallery of characters in search of a plot. It bears some resemblance to the “anti-plays” of absurdist writer Eugene Ionesco (who also wrote on a Hermes 3000), but Kotzwinkle doesn’t embrace either aesthetic—Beat or Theater of the Absurd—with the seriousness of a true believer. Consequently, Hermes 3000 feels more like a literary exercise than a novel.

But back in the late ’60s and early ’70s, even mainstream publishers were willing to take a chance on young weirdos with a literary bent in the hopes of discovering the next Vonnegut or Brautigan. And with his very next novel, Kotzwinkle appeared to have transformed himself into the Brautigut every publisher was looking for.

The Fan Man, published in 1974, is the first-person stream-of-consciousness narrative of Horse Badorties, a drug-addled hippie who wanders New York City by day, talking to himself, ogling 15-year-old girls, and collecting a lot of useless junk to haul back to the various apartments in which he illegally squats at night. In a rapturous review in the New Republic, William Kennedy called The Fan Man “the funniest book of 1974.” Badorties, Kennedy wrote, was “an avatar for our time” in a “short, artfully structured, supremely insane novel about a freaky, quasi-Hindu-shmindu Brahman who is one with the ridiculously filthy, worn-out world.”

After the critical success of The Fan Man, Kotzwinkle could have made a comfortable living as a sort of east coast version of Richard Brautigan. Over the course of about 25 years (1957–82), Brautigan turned out 10 poetry collections and nine slender novels (several other books were published posthumously), most of which were about freaks and social outsiders living in Oregon and California.

But Kotzwinkle has never been one to settle into a comfortable groove. Swimmer in the Secret Sea tells the story of Johnny and Diane Laski, who lose their child during the birthing process and must cope with their immense sense of loss. Kotzwinkle’s sharp insights about such a devastating event give the story the emotional heft of a major work of fiction. The similarities between author and male protagonist—both are married, childless artists who live in relative rural seclusion—suggest that the story might be at least partially autobiographical. In Ian McEwan’s 2012 spy novel Sweet Tooth, the narrator Serena Frome and her associate Thomas Haley are both fans of 20th-century fiction but can only agree on the excellence of one book:

… he couldn't interest me in the novels of John Hawkes, Barry Hannah or William Gaddis, and he failed with my heroines, Margaret Drabble, Fay Weldon and Jennifer Johnston. I thought his lot were too dry, he thought mine were wet, though he was prepared to give Elizabeth Bowen the benefit of the doubt. During that time, we managed to agree on only one short novel, which he had in a bound proof, William Kotzwinkle’s Swimmer in the Secret Sea. He thought it was beautifully formed, I thought it was wise and sad.

Swimmer in the Secret Sea was published in 1975, and over the next four years, Kotzwinkle turned out one winner after another, no two of which were alike. Doctor Rat (1976) is a fantasy novel in which Kotzwinkle channels the thoughts of rats and other creatures in a medical research facility. Ostensibly a denunciation of animal cruelty, the book can also be read as an allegory about the Holocaust or simply an exploration of man’s inhumanity. Oddly, it is often very funny and won a World Fantasy award.

Fata Morgana, published in 1977, combines elements of the Sherlock Holmes canon, magical realism, and the Victorian sensation novel. The following year, he published Herr Nightingale and the Satin Woman, a graphic novel (illustrated by Servello) about a detective’s search for a German officer shortly after the end of World War II. As one satisfied Amazon customer notes:

This book is amazing—a pulpy, mystical noir graphic novel from 1978, when graphic novels weren’t a thing. Beneath the pulp adventure exterior lies some straight-up Kafka/Burroughs insanity as well. Everyone I show it to loves the layout and imagery, and is amazed by it. I’ve bought it three times because people keep borrowing it and never giving it back.

Two years later, in 1980, Kotzwinkle returned with Jack in the Box, a collection of vignettes, many of them very raunchy, about an American boy growing up in the 1940s and ’50s. The book opens with a quote from Mark Twain: “Persons attempting to find a plot will be shot.” Jack in the Box appears to be less a novel than a comically exaggerated version of Kotzwinkle’s own boyhood, somewhat in the same vein as James Thurber’s My Life and Hard Times, but with lots of smut. In 1990, New Line Cinema released a film adaptation, re-titled Book of Love, with a screenplay by Kotzwinkle. The PG-13 theatrical release was fairly tame, but the R-rated director’s cut, released on DVD in 2004, comes closer to capturing the spirit of the book.

1982 would prove to be the high-water mark of Kotzwinkle’s career, at least in terms of commercial success. That was the year he published a novelization of Melissa Mathison’s screenplay for Steven Spielberg’s 1982 blockbuster E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. It appeared as a paperback original in June and by August it had already been through 19 reprints. Eventually, it became the first novelization ever to make it to the top of Publishers Weekly’s list of the 10 bestselling fictions of the year. A lot of novelizations are written by cash-strapped writers in need of an easy paycheck, but Kotzwinkle hadn’t gone to Hollywood looking for work. Hollywood came to him. Spielberg had been a fan of Kotzwinkle’s writing ever since he happened upon a copy of The Fan Man back in the mid-1970s. He knew that E.T. was going to be a special film, and he wanted the novelization to be special as well.

Kotzwinkle was provided with an early draft of Mathison’s script to work from, so his novel differs from the film in a number of significant respects. The film is told mainly through the eyes of Elliot Taylor (Henry Thomas), the 10-year-old boy who first befriends E.T. Although the novel is written in the third person, it is told mostly from E.T.’s point of view, which dramatically alters how the reader experiences its events. The novel is also a lot less sentimental and contains more adult humor than the film. Elliot’s mother, Mary Taylor (played by Dee Wallace in the film), is single in both versions of the story. But in Kotzwinkle’s novel she spends a good deal of time pining for the sex life she has been denied ever since her husband left and reflecting ruefully on the costs of parenthood:

If anyone knew in advance what it was to raise kids, they’d never do it.

and

How nice it must have been when children went to work in coal mines at the age of nine. But those days, she felt, were gone forever.

In both the film and the novel, E.T. is a botanist from a faraway planet. In the film, E.T. possesses the power to resuscitate dead houseplants. In the book, he can also communicate with them telepathically, and Kotzwinkle includes a number of short, humorous asides from vegetables. Many of Kotzwinkle’s books feature the thoughts and words of animals or insects, and in E.T. we are occasionally privy to the observations of Harvey, the Taylor family’s pet dog:

Food had not been forthcoming all day. Everyone had forgotten the main business around here, of feeding dogs. What was going on? Was it because of the monster upstairs? I will have to eat him, thought Harvey, quietly.

One of the most curious differences between the book and the film is the brand of candy Elliot uses to lure E.T. into his house. Throughout the book, Elliot feeds E.T. M&Ms, which were referenced in early drafts of the script. But when Universal Pictures sought permission from Mars Incorporated to use them in the film, Mars declined, fearing that associating their brand with a space alien would turn children against it. So, Universal turned to the Hershey Company who granted the filmmakers permission to use Reese’s Pieces instead. Similar in appearance to M&Ms, Reese’s Pieces had just been introduced in the US a couple of years before the film’s release and weren’t yet very popular. After the film came out, sales soared by about 300 percent.

Though they share the same DNA, Kotzwinkle’s book has a very different agenda to Spielberg’s film. From one page to the next, it can veer from the slapstick comedy of the Marx Brothers to the stoner humor of Cheech and Chong. Spielberg liked it so much that he sketched an idea for a sequel and asked Kotzwinkle to expand it into another novel. Published in 1985, E.T.—The Book of the Green Planet proved to be a successful follow-up, but without a blockbuster film to tie into, its sales figures were not as impressive as those of the original.

Although he would never again recapture the cultural prominence he had enjoyed in 1982, Kotzwinkle continued to produce a wide array of literary work, including children’s picture books, short-story collections, novel-length poems, and more. Aside from E.T., his most popular novel is probably The Bear Went Over the Mountain (1996), a gentle spoof of the publishing industry. It tells the story of a bear who stumbles upon the manuscript of an unpublished novel discarded by its disillusioned author and decides to take it to New York City and publish it as his own work. It was subsequently nominated for a World Fantasy Award (Kotzwinkle’s book, that is, not the bear’s).

Since the turn of the century, Kotzwinkle’s output has consisted primarily of a series of children’s books about Walter the Farting Dog. But then, in August 2021, he gave us Felonious Monk. The book was well reviewed and then optioned for a TV series by Fox Entertainment. The follow-up novel, Bloody Martini, is even better. It contains a wealth of fascinating characters, including a 15-year-old femme fatale known as Ruby the Forbidden Fruit, described by those unlucky enough to have crossed her path as “a walking electric chair,” “a manipulating little bitch with the mind of a video game,” and “the devil child … educated by Lucifer.” When Martini tries to locate Ruby in a seedy part of town, a drag queen tells him, “I haven’t seen her around for a while. Maybe hell had a recall on her model.”

But Bloody Martini is more than just a gripping crime novel. It is also an examination of (and ode to) the working-class towns across America hollowed out by globalization and the off-shoring of blue-collar jobs. Coalville is a ghost-haunted ruin, the abandoned mines of which now serve as convenient places to dispose of dead bodies. Seams of unmined coal have caught fire far below the surface of the town, and the landscape is pockmarked with crevices where the smoke (and occasional flames) of these fires are visible to the naked eye, polluting the air and making visibility more difficult. Deaths of despair are common here and Russian mobsters abound. At one point in the novel, Martini is part of a three-car chase that ends at a local garbage dump:

We entered a dystopian world of abandoned furniture, battered stoves, refrigerators, toilets, bathtubs. Adding to the feeling of a failed civilization was a huge crack that had opened at the heart of the dump, a mine fire having burned right up through the surface.

Dystopias are not new in Kotzwinkle’s work. Even his yuletide novel, Christmas at Fontaine’s, is less Miracle on 49th Street than Nightmare on Elm Street (not surprising, since Kotzwinkle wrote the story on which Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master was based). But I imagine it is difficult to write well about a fallen world unless you once loved it at least a bit, and Kotzwinkle’s fondness for the lost land of his Pennsylvania boyhood is palpable.

Kotzwinkle hadn’t published a novel since 2005. Now, at 84, he has published two in the space of 19 months. It’s a late-career trajectory somewhat similar to that of 89-year-old Cormac McCarthy, who hadn’t published a novel since 2006, and then released a brace of connected novels in late 2022. But McCarthy’s return was heralded far and wide, generating hundreds of column inches in newspapers and magazines across the globe. Alas, Kotzwinkle’s accomplishment, like the man himself, exists in a sort of twilight zone—highly admired by those who are aware of it, but not nearly as well-known as it should be. I fear that Kotzwinkle is the kind of writer who—like Philip K. Dick or Jim Thompson or Patricia Highsmith—won’t get his due from the literary establishment until after he is dead and gone. And what a bloody shame that would be.

AN INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM KOTZWINKLE

The following interview was conducted over email in mid-February by Kevin Mims for Quillette.

Kevin Mims: Are you a longtime fan of mystery and crime fiction?

William Kotzwinkle: When I began to get published, Jorge Borges was formative for me. He wrote of the mysterious nature of the world, where the rational meets the mythological. That was in the late ’60s and I and a great many young people in Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side were steeped in this quest for the unknown, owing to drugs and the import of Eastern religion. It wasn’t until decades later that I became acquainted with the work of Raymond Chandler and realized he too had seen the mysterious edge of the world. This was surprising because his style is hard-bitten and world-weary. His hero, Philip Marlowe, is like someone who’s been killed a dozen times but is somehow still alive. Marlowe has seen it all and can describe something as ordinary as a flight of stairs, yet show its metaphysical aspect. Along with that, there are descriptions like this: “He was as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food.”

KM: Even before Tommy Martini came along, crime and mystery were a big part of your work. Could you tell me a bit about why that is?

WK: In childhood I had a friend whose father was in prison. My friend was more daring and more inventive than the rest of us—he made his own working pistol out of a toy cap gun. He went on to become a professional criminal. I’m intrigued by destinies such as his. I knew a high-society conman—a lawyer who specialized in handling estates for wealthy senior citizens; he manipulated them into making him large gifts, then convinced them to put him in their will. He came from a good family himself, was sophisticated, thoughtful, amusing. But he woke in the middle of the night knowing there was something evil in him against which he was powerless. In casual conversation with him it wasn’t possible to explore the passageways of his soul but on paper it’s possible, and I find characters like his an irresistible challenge.

KM: Do you have any favorites among crime novelists, or among fictional detectives?

WK: Raymond Chandler tops my list of crime novelists because of lines like this: There were a couple of colored feathers tucked into the band of his hat, but he didn’t really need them. I can see that character perfectly, a rough guy in a gaudy suit, and Chandler left it up to me to complete the outfit.

As for fictional detectives, it’s hard to beat Sherlock Holmes.

KM: During the era when you were first breaking into print—the late ’60s and the ’70s—American crime fiction was enjoying one of its most fertile periods, producing novels such as The Godfather, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, Ragtime, The Choirboys, The Great Train Robbery. Did that have any effect on your own writing of the era?

WK: The Godfather was wonderfully entertaining but I wasn’t influenced by the style. It was the images, like the severed head of a race horse on a pillow, that are unforgettable. It’s the only book I’ve read of those you mentioned. At that time I was discovering my own voice, which required isolation. One’s contemporaries can be devastating in their influence on a young writer. They can make you feel inferior or they can send you off on ground that was very suitable for them but quicksand for you.

KM: You seem to have put a lot of thought into the vehicles that your characters drive. Can you talk about that at all?

WK: Well, Tommy Martini was brought up in a family that worked on vehicles. When you sit in the cab of a monster tow truck looking down on the world, you’re transformed into an absolute king of the road, towing the unfortunate. The character of the truck becomes a quality of the character driving it.

When I hear some young person racing through city streets, his aftermarket muffler singing through the gears, I feel drawn into his dream. Hemingway wrote a poem called Along with Youth, and it expresses what I feel in such moments.

I knew a distinguished photographer who drove a secondhand hearse. Such an act smacks of a real joker, laughing as he drives through town. Let them think what they want. He ended by shooting himself and I wondered, did his hearse contribute to his suicide? Did it deepen his morbidity? Or was it really just a joke? It’s probably sitting in a junkyard now, gone from the world as he is.

When master motorcyclists fly by me in traffic, demonic in their contempt for those who move at lesser speed, I’m humbled by their daring, and much as I want to be back on a motorcycle I leave that dream to them. My days on a motorcycle ended when my wife fell off the back of mine.

I’ve been in vintage muscle cars that bring lost time back, their awesome power carrying me back to the town where I grew up. In that town, a car meant freedom, fornication, and scaring yourself to death. So in my books, the way a person drives says a lot about their nature. And what they drive rounds out the picture.

KM: You grew up Catholic and once tried to become a monk, two things that seem to inform the Tommy Martini books. Any reason why you decided to revisit those aspects of your past now?

WK: Growing up Catholic is certainly an indelible experience. In the Tommy Martini books, I began to sketch a young man running from law enforcement. I realized that a monastery was an excellent hideout because I knew that monastic environment. Tommy could live there but it would require a dramatic balancing act because he was inclined to be violent and rebellious. The peace and solemnity of a monastery would make demands he could not always meet. I liked that predicament and could see that it had the architecture for a series.

KM: What kind of response have these Martini novels gotten from longtime readers of your work?

WK: Mostly positive. I have readers who wish I had written nothing but Fan Man novels. But the era of Flower Children in New York City has vanished. When a one room apartment on the Lower East Side costs $5,000 a month the shape of a Fan Man novel would require some time-twisting. Of course, my continually-stoned hero taking on 21st-century landlords and hedge fund managers is tempting.

KM: Are you planning more installments in the Tommy Martini series? If so, can you tell us yet where we may find him next?

WK: Tommy’s next adventure will take him from the monastery to the professional wrestling world of Las Vegas. Tommy, in his youth, was an Olympic-level wrestler so he’ll fit right into that world. And his Mafia family connections will be of some use. Nowadays the Mafia no longer own the big resort casinos but they do own some of the smaller gambling joints, which is even better. One of those owners made a brief appearance in Book 1, and I like the way he speaks. Criminals often have amusing ways of expressing themselves.