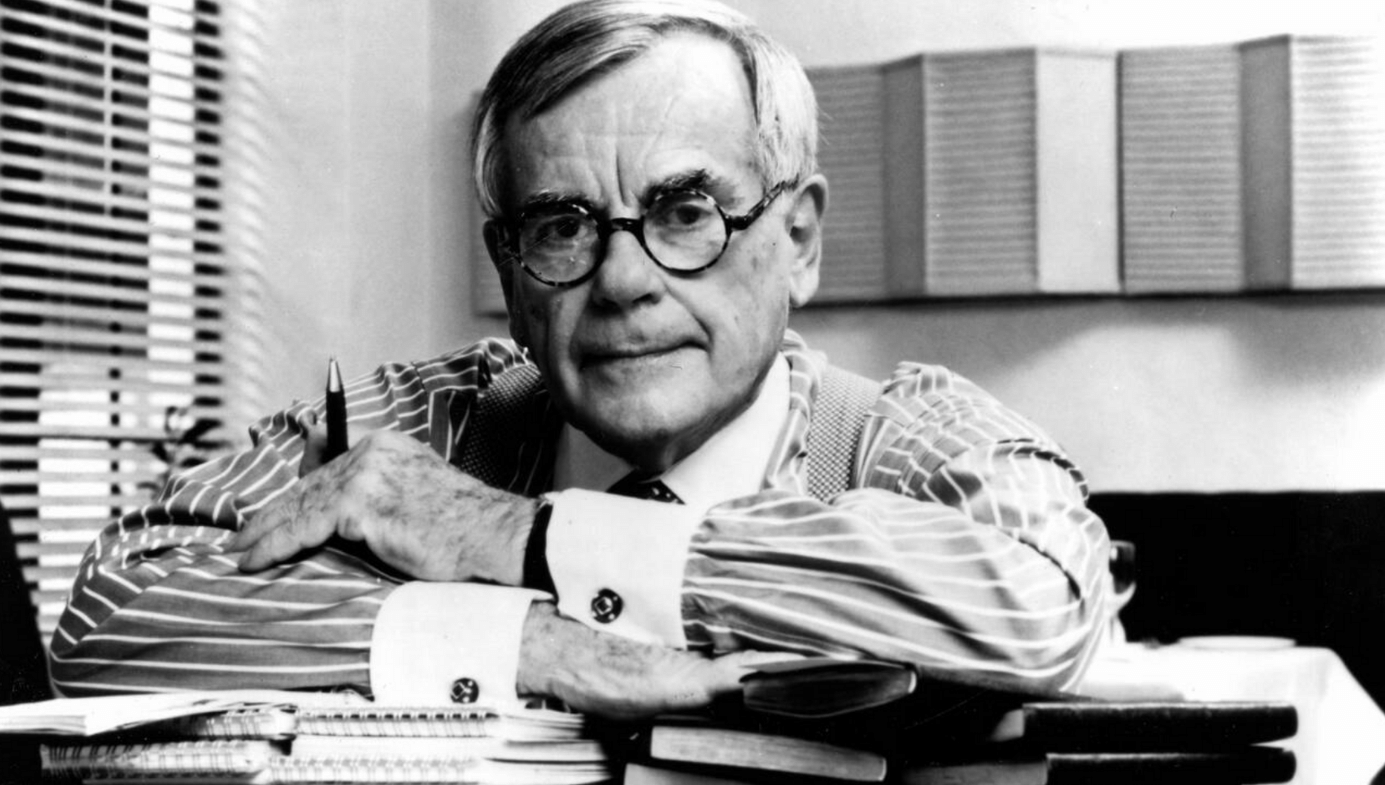

Dominick Dunne, Writer of Wrongs

The success of the HBO TV series Succession and the recent feature film House of Gucci are proof that the wretched excesses of the fabulously wealthy never lose their audience appeal. Nobody knew that better than the late novelist and journalist Dominick Dunne. He spent the last 30 years of his life chronicling the lives (and deaths) of America’s uber-privileged. He did so as a journalist for Vanity Fair, where he covered celebrated courtroom trials, and he also did it in novels such as The Two Mrs. Grenvilles, People Like Us, A Season In Purgatory, and An Inconvenient Woman, all of which were bestsellers.

He was part of an astonishingly talented clan of creative artists. His brother, John Gregory Dunne, was a successful journalist and novelist. John’s wife, Joan Didion, is an even more successful journalist and novelist. The couple also collaborated on several screenplays, including one for the wildly successful 1976 version of A Star Is Born, which starred Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson. Dominick Dunne’s daughter, Dominique, was a promising young actress who was murdered (technically, manslaughtered) by an ex-boyfriend three weeks before her 23rd birthday. Her brother, Griffin Dunne, is a talented actor (An American Werewolf in London, After Hours) and director (Practical Magic, Addicted to Love) who also made a memorable appearance as celebrity psychologist Alon Parfit in an episode of Succession.

Nobody has ever claimed that Dominick was the most gifted writer of the Didion-Dunne clan. Nobody until I decided to write this, that is. Dominick was seven years older than John Gregory. They were born into a wealthy Connecticut family. But they were Roman Catholics raised in a very Protestant milieu, which left each man with a lifelong sense of being an outsider (Joan was raised a Protestant but, a military brat, she traveled around a lot during her childhood, which also left her feeling like a perpetual outsider). Whereas Joan and John Gregory both became professional writers early in life (beginning in the 1950s, they became frequent contributors to Vogue, Time, the Saturday Evening Post, and other slick magazines), Dominick took a lot longer to find his footing in the literary world. World War II interfered with his plans. He was drafted into the Army while still in high school and earned a Bronze Star for his heroism at the Battle of the Metz, in France. Following his stint in the Army he enrolled in Williams College, and after graduation he moved to New York and got a job in television production. Later, Humphrey Bogart persuaded him to move to Hollywood, where production jobs were more plentiful.

In 1954, Dominick married Ellen Griffin. The union produced five children, only three of whom lived to adulthood. Dominick and Ellen split up in 1965, but remained close until her death in 1997. Dominick produced the 1971 film The Panic In Needle Park (which gave Al Pacino his first starring role), and hired Joan and John Gregory to write the screenplay. After that, he became a kind of cultural gadfly, attending parties with jet setters and Hollywood stars, subordinating his career to the allure of alcohol and recreational drugs. At one point he had to borrow $1,000 from his daughter just to pay his rent. The success of A Star Is Born elevated The Didion-Dunnes to Hollywood’s A-list at the same time that Dominick was rapidly falling into disgrace. John Gregory and Joan had shrewdly secured a piece of the film’s profits, which made them fabulously wealthy pretty much overnight, and Dominick’s jealousy got the better of him. Eventually his drinking and drug abuse became so extreme that he had to drop out of the Hollywood scene altogether. In an essay he wrote for Vanity Fair after John Gregory’s death in 2003, Dominick provided this sketch of what happened to him during this period:

I had begun to fall apart. Drink and drugs. Lenny [his wife’s nickname] divorced me. I was arrested getting off a plane from Acapulco carrying grass and put in jail. John and Joan bailed me out. As I was falling and failing, they were soaring and gaining renown. When I went broke they lent me $10,000. A terrible resentment builds when you’ve borrowed money and can’t pay it back, although they never once reminded me of my obligation. That was the first of the many estrangements that followed. Finally, in despair, I left Hollywood early one morning and lived for six months in a cabin in Camp Sherman, Oregon, with neither telephone nor television.

After regaining his sobriety, Dunne left Oregon and moved to New York City. His first big break as a novelist came about in an odd way. In 1976, longtime Los Angeles Times gossip columnist Joyce Haber left the paper to write a salacious novel whose characters were thinly based on various film stars of the era. Her book was called The Users and became a huge bestseller. Alas, Haber was a one-hit wonder as a novelist. Though she lived until 1993, she never wrote another one. But the publishing world couldn’t allow a commercial juggernaut like The Users to remain a stand-alone property. In the early 1980s, when it became clear that Haber would never be able to produce a sequel, Dominick Dunne was given the assignment, perhaps because, like Haber, his head contained a wealth of Hollywood gossip. The book, Dominick’s first novel, was published in 1982 by Simon and Schuster under a horribly ungainly title—The Winners: Part II of Joyce Haber’s The Users. In both the hardcover and paperback editions Haber’s name is featured much more prominently than Dunne’s. Nonetheless, in 1982, at the age of 57, Dominick Dunne became a published novelist. He didn’t have long to relish his success.

The book was published in April of that year. On October 30th, his daughter Dominique was strangled by her ex-boyfriend, John Thomas Sweeney. Her brain was deprived of oxygen for so long that she fell into a coma from which she never recovered. She died five days later. The horror of Dominique’s manslaughter was compounded by the leniency shown to Sweeney by his trial judge. Sweeney, who had a history of beating up women, was given just a six-year prison sentence (he would be paroled after serving only three-and-a-half years). Dunne was so outraged by the sentence that he yelled out at the judge in the courtroom. Dunne, his ex-wife Ellen, and his son Griffin were all radicalized by the verdict. Ellen and Marcella Leach (whose daughter Marsy was killed by a boyfriend a year after Dominique’s death) co-founded a victims’ rights organization called the California Center for Family Survivors of Homicide. When Sweeney, after his parole, was hired as the head chef at a trendy Santa Monica restaurant, Griffin and his mother stood outside the restaurant protesting. Eventually, Sweeney quit the restaurant and moved away. But Dominick hired notorious Hollywood fixer and private detective Anthony Pellicano to keep an eye on Sweeney’s whereabouts, so that he could notify future employers and girlfriends whenever Sweeney drifted into their orbit.

Dominique’s death also radicalized her father’s professional life. During the trial, he kept a diary that was eventually published in Vanity Fair under the ironic title “Justice: A Father’s Account of his Daughter’s Killer.” After that, much of his fiction and his journalism focused on sensational murders committed by lovers or spouses of the victim. His first true solo novel was The Two Mrs. Grenvilles, which was inspired by a sensational 1955 case in which a famous socialite was shot dead by his wife. Eventually Dunne started focusing primarily on cases where women were murdered by politically powerful or socially prominent men. His 1988 novel People Like Us is semi-autographical and deals, in part, with a father struggling to come to terms with his daughter’s murder. His 1990 novel, An Inconvenient Woman, is based on the life and death of Vicky Morgan who, at 17, became the mistress of 54-year-old married multi-millionaire Alfred S. Bloomingdale. When Bloomingdale later discarded her, Morgan fell upon hard times. She sued Bloomingdale for “palimony,” but while the case dragged out, she wound up working as a prostitute and living with an unstable friend she had made while staying at a rehab center. Eventually that friend murdered her. Dunne’s 1993 novel, A Season In Purgatory, was a fictionalized account of the 1975 murder of 15-year-old Martha Moxley by Michael Skakel, a relative of the late Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Moxley, born on August 16th, 1960, was almost the same age as Dominique Dunne, born November 23rd, 1959. His 1997 novel, Another City, Not My Own, was a fictionalized account of the murder of Nicole Brown Simpson and the trial of her ex-husband, O.J. Simpson.

In an eerie coincidence, the plot of The Winners, written and published before Dominique’s death, bears many similarities to her story. The protagonist of The Winners is Mona Berg, a ruthless Hollywood agent who discovers that her lover, an upcoming young actor named Frankie Bozzaci, intends to leave her. She shoots him dead and then tells the police that she mistook him for a prowler. Later, a friendly grand jury determines that the murder was accidental, and Mona walks away, largely unscathed. The book is lightweight and entertaining. The tragic deaths are generally presented as melodrama without any effort at criticizing the social injustices that made them possible. Mona, though a monster, is the star of the book and triumphs in the end. Had Dominique not been murdered, her father would probably have gone on producing lively name-dropping pop fictions that celebrated their wealthy but amoral protagonists in an over-the-top fashion. But that’s not what happened.

In a classic 1941 work of literary criticism called The Wound and the Bow, Edmund Wilson argued that many famous authors—Dickens, Kipling, Edith Wharton, Hemingway, Joyce, etc.—achieved greatness, in part, by compensating for a horrible psychological wound. (Dickens’s father was sent to debtors prison when Charles was 12; born in India, Kipling was sent at the age of five to a boarding school in England, a horrible experience that marked him for life.) Dunne suffered plenty of wounds in his life (a hateful father, a painful divorce), but it seems that it was the death of his daughter that transformed him from a pop fiction hack into a serious chronicler of his times. After 1982, his books took on a greater moral weight, and he never again celebrated the successes of his most wicked characters.

Many of Dunne’s novels feature a gadfly/journalist named Augustus “Gus” Bailey, who bears a strong resemblance to Dunne himself. Like Dunne, Gus was once married, and he and his wife were at the center of a fascinating group of writers, artists, and filmmakers. Like Dunne, Gus is a recovering alcoholic. Like Dunne, Gus once worked in the film business but later became a freelance journalist specializing in the lives of the rich and famous. The word “bailey” means “the outer wall of a castle,” and no doubt Dunne was aware of that fact. Gus is always standing a bit outside the fabulous castles of Park Avenue or Beverly Hills, peering at the celebrities gathered inside. And even when he is invited in, he remains—as Dunne did throughout his life—psychologically an outsider.

But the strongest link between Dunne and Bailey is that they both had daughters murdered by a boyfriend. Both men’s lives and career trajectories are dramatically altered by this fact. Gus Bailey’s daughter, whom we first hear about in 1988’s People Like Us, was named Becky, and she was strangled by an ex-boyfriend named Lefty Flint. Unbeknownst even to his closest friends, Gus attends regular meetings of a group of bereaved parents, all of whom are mourning the death of a murdered child. At one point, Gus tells another grieving parent, “No one really understands. All our friends are loving and helpful during the time of the tragedy, but then they withdraw into their own lives, which is only natural, and soon you can see a glaze in their eyes when you bring it up because they don’t want to talk about it anymore, and it is the only thing that is on your mind. That’s why these groups are so helpful. No one really knows what you are going through like someone else who has been through it.”

People Like Us is largely autobiographical. Just as Dunne hired sketchy Hollywood PI Anthony Pellicano to keep an eye on his daughter’s killer after the man was released from jail, Gus Bailey hires sketchy Hollywood PI Anthony Feliciano to do the same to the man who strangled Becky. Like Gus, Dunne never stopped obsessing over the killing of his daughter. When he wasn’t fictionalizing real murders, he was reporting on them for Vanity Fair and other publications. He covered numerous famous murder trials, including the Simpson trial, the Claus von Bülow trial, the Skakel trial, the William Kennedy Smith trial, and the trial of the Menendez brothers. All of this seems to have sprung from the murder of his 22-year-old daughter. Alas, though Gus Bailey eventually tracks down Lefty Flint and shoots him, Dunne never got that kind of closure. He had to live vicariously through his alter ego. Dunne died in 2009. Sweeney lives on.

Curiously, John Gregory Dunne’s first novel, published five years before his niece’s death, was inspired by the murder of 22-year-old Elizabeth Short, aka The Black Dahlia. In his second novel, published the year after Dominique’s death but almost certainly written before she died, the title character’s 18-year-old daughter is murdered gruesomely in the opening pages. And his fourth novel, 1994’s Playland, is about the mysterious disappearance of a young female movie star. Joan Didion’s 1970 novel Play It As It Lays is about a young Hollywood actress whose life is spiraling out of control. It is as if poor Dominique was haunting her family’s fiction even before her tragic death.

It must be conceded that Dominick Dunne wasn’t as gifted a wordsmith as his sister-in-law. But his novels tend to be much more compelling than hers. He knew how to tell a story that was both an indictment of a particular killer and of the society that nurtured him. He knew how to write about a small personal tragedy, usually involving the murder of a powerless young woman by a prominent man, as well as the large media sideshow that such tragedies often beget. Joan Didion once described him as the Anthony Trollope of his era and, indeed, Dunne claimed that, like Trollope, his subject was “The way we live now.” Didion’s prose is often noted for its coolness. Dunne’s was anything but. After Dominique’s death he became a man possessed. That type of writer rarely writes cool, elegant sentences. Usually, he allows form to follow function, and the function of much of Dunne’s work was to right a tragic wrong. He took a fictional baseball bat to the heads of a lot of actual bad guys. And when he wrote about the subject that was most painful for him—his daughter’s murder—he could be quite moving. Here, using his fictional alter ego Gus Bailey, whose wife is nicknamed Peach, he writes about attending Sweeney’s trial with his own ex-wife, Ellen:

Nearly three years earlier Gus and Peach Bailey, separated in marriage but brought together by adversity, had sat side by side in a courtroom for seven weeks, a kind-of couple again. She needed him then, as much as he needed her, and they became, in a way neither had tried to explain to the other, closer than they had been when they were close. Less than ten feet from them sat Lefty Flint, the killer of their child, holding a Bible in his hands and with a look of piety on his face, dressed with the black-and-white simplicity of a sacristan in a seminary, although he was previously known to be a mocker of God. Peach had shuddered, seeing through it all, the sham of justice they were witnessing, knowing how it was going to end, that poor sweet Becky was going to be forgotten and Lefty Flint was only going to get his wrist slapped, in the name of love.

In many ways Dunne seems to have patterned his literary career after his friend Truman Capote’s. The two men are an odd study in contrasts and commonalities. The author of In Cold Blood and Music for Chameleons reported on true-life crimes in the prose of a novelist. Dunne wrote about fictional crimes in the prose of a tabloid reporter. Capote was about as openly gay as it was possible to be in his lifetime (1924–1984). As a boy, Dunne was teased mercilessly by his father for being a “sissy.” After divorcing Ellen, Dunne never remarried and claimed in interviews that he was completely celibate. It’s possible that he was a closeted homosexual, which might have further added to his sense of being a lifelong outsider. Dunne and Capote were born about a year apart. Both men attended high school in Connecticut. Capote enjoyed huge early success and then a fairly long fallow spell prior to his early death at the age of 59 (his enemy Gore Vidal called Capote’s death “a good career move”). Dunne didn’t become a novelist until he was in his 50s, but after that he enjoyed nearly 30 years as a popular novelist and prominent journalist. Both men were obsessed with celebrity and gossip.

Probably the most entertaining thing Dunne ever wrote is Chapter 35 of the novel People Like Us. It describes the preparations for and execution of a grand New York high-society ball, which begins with a small tragedy and ends in absolute farce. Among other disasters, 10,000 live butterflies, imported from Chile, are released into the grand ballroom, fly upwards into the fluorescent lights, are burnt to death, creating a noxious stench, and then rain down upon the heads of the horrified guests below (including the First Lady of the United States). The chapter was probably inspired by the famous black and white ball that Truman Capote threw on the night of November 28th, 1966, at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. Widely regarded as “the party of the century,” its guests included the First Lady of the United States. Capote got the idea from Dunne, who had thrown a spectacular black-and-white ball two years earlier in Los Angeles. Dunne invited Capote to his ball. Capote didn’t invite Dunne to his.

People Like Us, which could easily have been titled Crazy Rich Caucasians, might well have gone down as the definitive portrait of greed and wretched excess among New York City’s high-rollers of the Reagan Era, if not for the fact that, seven months before its publication, Tom Wolfe had made his debut as a novelist with The Bonfire of the Vanities. Wolfe’s book was the most talked-about novel of the year, which made it difficult for similarly themed fiction to get much attention. People Like Us sold well and was made into a TV mini-series, but it didn’t become as iconic as Wolfe’s book. Which is a shame because, in some ways (its sympathetic examination of the AIDS crisis, for instance), Dunne’s novel is a much better snapshot of the times. Like many of his novels, it also contains words of solace for those who have lost a loved one to violence. Through his mouthpiece Gus Bailey, Dunne tells those readers: “I have no answers. I know of no secrets to assuage your pain. I can only tell you that you go on. You carry on somehow. You live your life. You work hard. In time you’ll go to films and parties again. You’ll see your friends and start to talk about other things than this. You’ll even learn to laugh again, as strange as that may seem now, if you allow it to happen.”

But Dunne’s books are not lugubrious. They are often witty and playful in their examinations of the privileged class. And they are filled with insights into how the very rich think, like these:

A lady can take her chauffer to bed, but she can’t take him out to dinner, Loelia. I’m surprised you of all people didn’t understand that.

There’s nothing the rich enjoy more than a bargain, especially a bargain that is reserved exclusively for them.

Nothing depletes a fortune like divorce these days.

You can buy anything you’re willing to pay too much for.

“What I learned a long time ago is to sell a company, or a hotel, or a business as soon as I start to love it.” “I don’t understand that,” said Mickie Minardos. “If you love a company, why do you sell it?” Elias looked at Mickie. “That’s why you’re not rich,” he said.

The Didion-Dunne clan left us a lot of good books. Alas, John Gregory Dunne seems already on the way to being largely forgotten. The MFA programs of the future will probably steer students to the writings of Joan Didion, who remains as highly regarded as ever. But for anyone who really wants to know what the violence- and celebrity- and wealth-besotted America of the late 20th century was like to live through, how dangerous it was for vulnerable women and those who lacked money or power, a good place to start would be the novels of Dominick Dunne. He’s never been accorded much respect by serious literary snobs, but the same kind of common readers who made household names out of the likes of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Daphne du Maurier, helped turn Dominick Dunne into a bestselling author. And that kind of reader usually knows a good storyteller when he sees one.