Religion

How the Christian Bible Became Separated Into ‘Old’ and ’New’

There is no firmly established technical term for the Bible in Judaism. The Hebrew scriptures may simply be referred to as “the Bible,” and the term “Jewish Bible” is sometimes used to distinguish it from the Christian Bible. In Hebrew, terms such as miqra (“scripture”) or kitve haqqodesh (“sacred texts”) are also common. In allusion to its tripartite division into the Torah (Law), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings), the Hebrew Bible is also called the Tanakh. This acronym, however, did not appear until the Middle Ages.

The terms “Old Testament” and “New Testament” for the two parts of the Christian Bible only emerged over time. The point of departure was the Greek term diathéke (testamentum in Latin). This word was used in the Septuagint (the Greek Old Testament) to translate the term berit, which denotes the covenant that God made with Israel or with humankind. The New Testament picks up this language, as in those passages where the term is used to describe God’s covenants with the Israelites.

The point at issue is the nature of the relationship between God and his people, which is defined by the Torah as God’s settlement. The broader sense of “testament,” or “compact,” can be seen in Paul’s Letter to the Galatians. Here, Paul illustrates God’s promise to Abraham, which is fulfilled through Christ, with the image of the testator, the provisions of whose testament (diathéke) remain in force until they are finally redeemed.

The contrast between the old and the new covenant is also to be understood against this background. Its origins can be seen in the third chapter of Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians. In this passage, Paul contrasts his own service on behalf of Christ with that performed by Moses and emphasizes that “ministry of the new covenant,” as a “service of the Spirit,” is more glorious than that which, as “a ministry of death,” is only engraved on “stone tablets”:

Not that we are competent in ourselves to claim anything for ourselves, but our competence comes from God. He has made us competent as ministers of a new covenant—not of the letter but of the Spirit; for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life (2 Corinthians 3:5–6).

In the same context, Paul also speaks of the “reading of the old covenant” and remarks that “Moses is read”; these are references to the practice of reading aloud from the Torah in synagogue services:

For till the present day, the same veil remains over the reading aloud of the old covenant, and it is not uncovered because it is [first] removed in Christ. But till today, whenever Moses is read, a veil is placed on their hearts (2 Corinthians 3:14–15).

Paul is drawing a polemical contrast between the old and the new covenant. The old covenant is represented by the Torah, for which he uses “Moses” as a metonym. A similar contrast of the two covenants appears in the Letter to the Galatians (4:21–31), where Paul interprets the sons of Abraham, one of whom he had by a slave woman, the other by a free woman, as two “covenants,” one of which leads to servitude, the other to freedom.

The “new covenant” (kainé diathéke) is also mentioned in the accounts of the Last Supper in Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians and in the Gospel according to Luke. Both describe the chalice used at the Last Supper as the “new covenant” (1 Corinthians 11:25; Luke 22:20). This image succinctly expresses the new bond that is forged between God and humanity in the celebration of the Eucharist. The idea of a new covenant recalls Jeremiah 31:31 (38:31 in the Septuagint):

‘The days are coming,’ declares YHWH, ‘when I will make a new covenant with the people of Israel and with the people of Judah.’

In the passage that follows, this new covenant is contrasted with the one God made with the “ancestors,” or “fathers,” when he led them out of Egypt. In the new covenant, God will make his law intelligible to people’s reason as well as writing it on their hearts.

The new covenant identified in the account of the Last Supper, and symbolized by the chalice, stands in this tradition. At the same time, the image of the “blood” of Jesus Christ (which is central to the doctrines of transubstantiation and consubstantiation in the communion service) harks back to the idea of a covenant sealed with blood first mentioned in the Bible in Exodus 24:8.

These two Old Testament texts from Jeremiah and Exodus also play a role in the Letter to the Hebrews, in which another mention of a “new covenant” appears. The text from Jeremiah 31:31–34 (38:31–34 in the Septuagint, from which the Letter to the Hebrews quotes) is cited verbatim in Hebrews 8:8– 12, where it is hinted that God has, through his proclamation of a new covenant, declared the existing one to be “obsolete” and therefore about to disappear (Hebrews 8:13). We also encounter in Hebrews the notion of the “blood of the covenant” from Exodus 24:8: “This is the blood of the covenant that YHWH has made with you.” This verse, which in Exodus refers to the sealing of the covenant between God and Israel through the blood of young oxen, is quoted in Hebrews 9:20, where it is linked to the blood of Jesus Christ—the blood that has been shed for the remission of sins once and for all time and which has established a new order. For this reason, Christ can be called the “mediator of a new covenant” (Hebrews 9:15).

Thus, whenever the New Testament mentions the old and new covenants, or testaments, it is not juxtaposing two “books,” but two orders. Talk of a “new covenant” or “new testament” picks up on the proclamation of a “new covenant” in Israelite-Jewish texts and relates it to God’s actions through Jesus Christ. Christ’s blood can thereby be interpreted as the “blood of the covenant”—in other words, the blood that seals the new bond.

The theme of the covenant also plays an important role in the Letter of Barnabas, a theological treatise written in around 130 CE. The principal content of this work is an explanation of how God’s covenant has been fulfilled through Jesus Christ. The treatise does not use the terminology of the old and new covenants, but it does refer to the “new law of Our Lord Jesus Christ,” which does not demand any burnt offerings or sacrifices but instead requires a person’s heart to offer praise to God. In a polemical way, the writer explains that Israel lost the covenant by turning to false gods. That is why Moses smashed the tablets of the law—so that the covenant of “our dear Lord Jesus might be sealed into our hearts.” As a result, the Christians are the heirs to the covenant that the Israelites had shown themselves unworthy of.

The juxtaposition of old and new covenants reappears later in the works of Justin Martyr, an early Christian theologian from the first half of the second century, and Irenaeus, who wrote his main work, Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies), in around 180. In the writings of both of these scholars—as in the New Testament texts—the two covenants denote, respectively, God’s actions in Israel and God’s actions through Jesus Christ. Using biblical references, they both refer to the gospel of Jesus Christ as the “new testament,” which has taken the place of the old one but has been instigated by the same God. These writers were not yet using that term to describe collections of biblical texts, however.

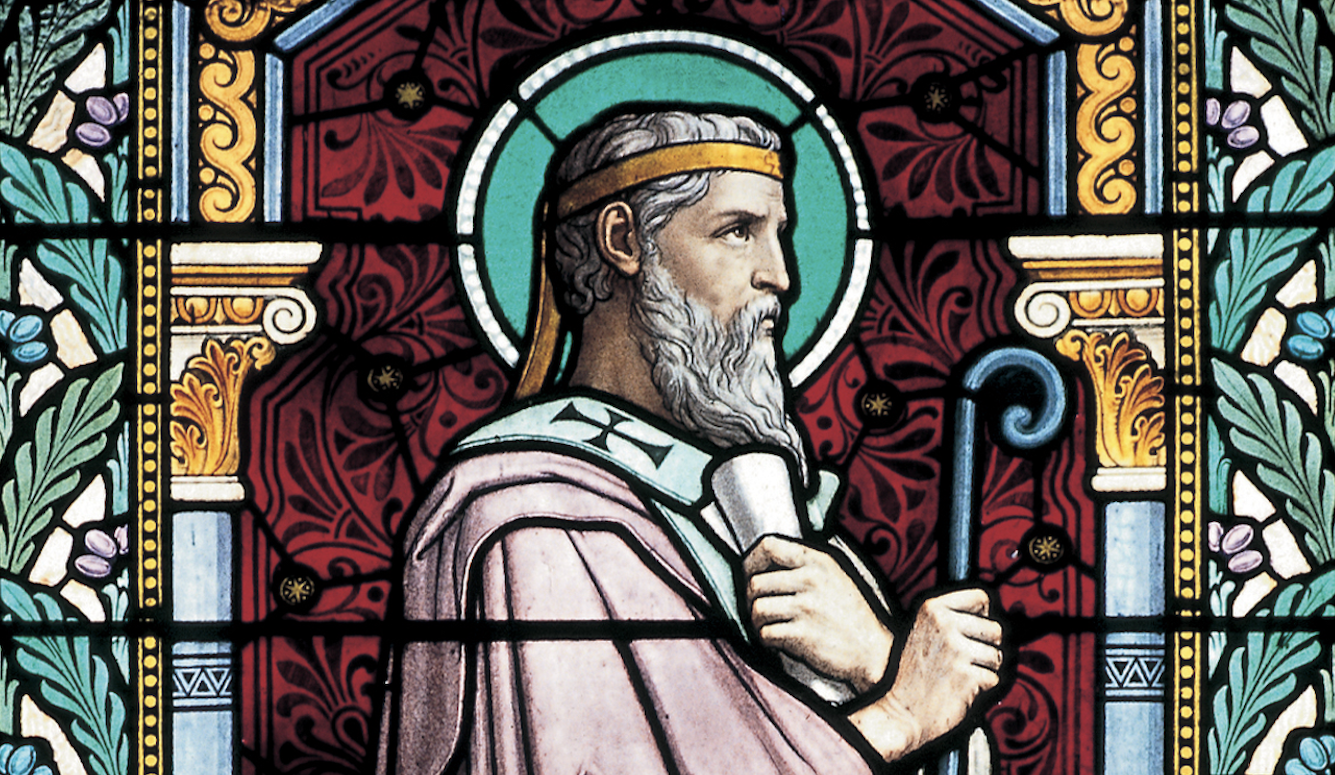

The first use of “Old Testament” (or “Old Covenant”) to designate the first part of the Christian Bible occurs in a letter written around 170 by Melito, the bishop of a town in Asia Minor called Sardes. Eusebius of Caesarea refers to the letter in his History of the Church. It contains a list of the books of the Old Testament (or the Old Covenant) which corresponds in large measure to the list found somewhat later in the works of Origen of Alexandria, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Athanasius: the five books of Moses, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, the four books of Kings (that is, the first and second books of Samuel and the first and second books of Kings), two books of Chronicles, the Psalms of David, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, Job, Isaiah, Jeremiah, the book of the 12 Minor Prophets, Daniel, Ezekiel, and Ezra.

Nehemiah is not named in its own right since it was presumably counted along with Ezra as a single book, which was the case in the Hebrew tradition until the early Middle Ages. Similarly unnamed is the book of Esther, which continues to be omitted from lists of biblical books from the fourth century, such as those drawn up by Athanasius and Gregory of Nazianzus. Thus, Melito’s list, like those compiled by other Christian theologians, includes only books with a Hebrew basis, and excludes the apocryphal or deuterocanonical books. Some early Christian writers made an explicit connection between the count of 22 books and the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. This tradition is also found in Jewish texts.

Melito’s letter, nevertheless, introduces no firm linguistic usage for the term “Old Testament,” nor does it contrast the “Old Testament” and the “New Testament” as two distinct books. Melito’s formulation “books of the Old Covenant” should be taken to mean that God’s “old covenant” with Israel is represented by the texts Melito cites, not that these texts themselves are called a “covenant” or “testament.” Melito does not use the expression “books of the new covenant” because he is responding in the letter to his friend Onesimus’ specific request for information about the number and sequence of the books of the Old Testament.

The designation “New Testament” for the books whose content reflects God’s new covenant with humanity first occurs in the writings of Clement of Alexandria and Origen, around the end of the second century and the first third of the third century. Some scholars have argued that the term can be traced back as far as about the year 140, to the works of the early Christian thinker Marcion of Sinope. Because Marcion’s writings have not survived, however, this theory relies upon critical analysis of Marcion provided by the Carthagian author Tertullian in the early third century. Even supposing Tertullian’s claim to be true, there is still no proof that Marcion used the term “New Testament” to denote an authoritative group of scriptures for the church.

We know that Marcion compiled his own collection of scriptures, which consisted of a particular version of Luke’s gospel and the letters of Paul that he had edited, and that this collection was roundly rejected by early Christian theologians. Even if he had indeed called this group of texts the “New Testament,” we would not be justified in taking this to refer to a particular section of the Christian Bible, in contradistinction to the “Old Testament,” for the simple reason that Marcion utterly repudiated the latter. Consequently, Marcion plays no significant role in the history of designations for the parts of the Christian Bible.

Around the end of the second century, the terms “Old Testament” and “New Testament” shifted from signifying two covenants to referring instead to the collections of scriptures that represent those covenants. We can see this process clearly by comparing use of the term “testament” by Irenaeus, who applies it to the covenants, with its use by Clement and Origen, who also apply it to the scriptures.

In the Latin-speaking realm, the works of Tertullian still contain both testamentum and instrumentum as translations of the Greek diathéke, though testamentum subsequently won out. The former polemical or negative use of “testament” in the sense of “(old) covenant,” which we find, say, in the letters of Paul, the Letter to the Hebrews, and the Letter of Barnabas, had now changed. Henceforth, the term came to refer exclusively to books, while the older meaning of “testament” as “covenant” receded.

From this starting point, “Old Testament” and “New Testament” became well established as the names of the two parts of the Christian Bible. Controversy did not arise again until the late 20th century, when some scholars called for the term “Old Testament” to be dropped as an alternative name for the Hebrew Bible on the grounds that the adjective “old” was pejorative. The name “First Testament” was put forward instead, though this suggestion has failed to catch on. First, it flies in the face of a long tradition; second, it does not take account of the ancient logic that old things, not new ones, were to be preferred; and third, the contrast of old with new—notwithstanding the judgmental presentation of the old and the new covenant in Paul’s letters and the Letter to the Hebrews—was not fraught with disparaging connotations when the Christian Bible was created.

Throughout the history of Christianity, both the Old and the New Testaments have been interpreted as evidence of God’s acts of salvation. The term “First Testament” is therefore an unnecessary neologism. What’s more, it would seem to imply that the New Testament should be renamed the “Second Testament,” a move that would be both historically and theologically questionable and misleading. Today, the terms “Hebrew Bible,” “Jewish Bible,” and “Old Testament” are used in a nuanced way that makes clear that the scripture collections of either Israel or Judaism are being referred to as great literature and as the Holy Scripture of both Judaism and Christianity.

Excerpted, with permission, from The Making of the Bible: From the First Fragments to Sacred Scripture, by Konrad Schmid and Jens Schröter. Translated from the German by Peter Lewis. Published by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.