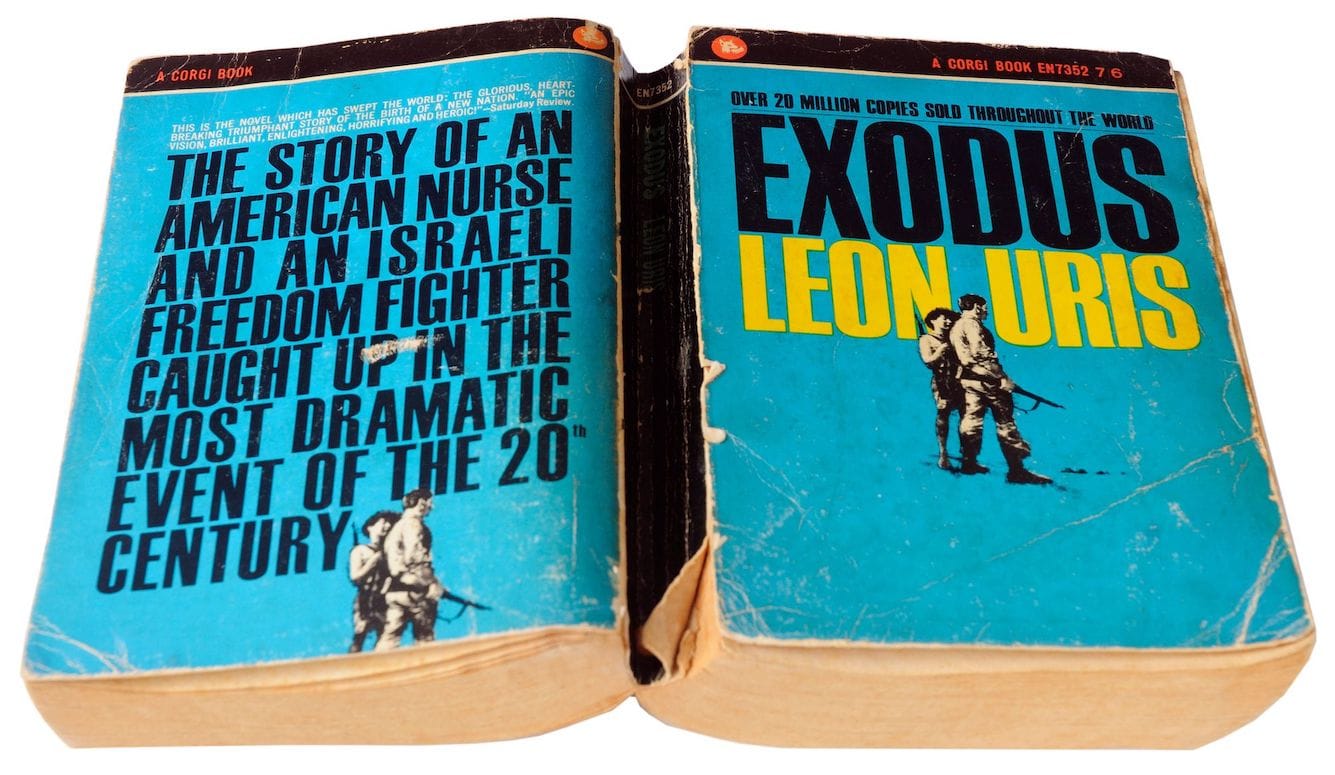

Sixty-five years ago this month, Doubleday and Company published Exodus, Leon Uris’s fictionalized account of the founding of the modern state of Israel. The book, Uris’s third, was an instant hit and quickly became the best selling American novel since Gone With the Wind, which had been published 22 years earlier. Exodus went on to become the most popular novel of 1959, topping a list that included Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and the first unexpurgated edition of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

According to 80 Years of Bestsellers: 1895–1975, a reference book compiled by Alice Payne Hackett and James Henry Burke, by 1975, Exodus had sold a total of 5,473,710 copies in all formats (hardback, paperback, book club, etc.) in the US alone. When you take into account the library copies that were borrowed, as well as the used copies that were sold or swapped, the novel had probably been read by at least ten million Americans by then, even though it was published when the population of the US was about half its current size. It was translated into dozens of languages and foreign sales accounted for millions more copies coming into print.

By 1975, Exodus had more copies in print in the US than many other perennial bestsellers, including The Cat in the Hat, Lolita, The Diary of a Young Girl, Rosemary’s Baby, Thunderball, Portnoy’s Complaint, The Good Earth, and From Here to Eternity. It has never been out of print and remains relatively popular to this day. On Amazon, it has garnered nearly 4,000 reader reviews, the vast majority of which are favorable. At Goodreads, the book has been rated by nearly 100,000 users (about 30,000 more than Portnoy’s Complaint), and has a cumulative score of 4.34 stars out of a possible five (well above Portnoy’s 3.70).

From the moment it was published, however, Uris’s novel was highly controversial. Uris, an American Jew born in Baltimore in 1924, set out to give Americans a tale that would sentimentally mythologize modern Israel in much the same way that Gone With the Wind had sentimentally mythologized the Confederacy. His Jewish characters tended to be larger-than-life heroes. His Arabs were mostly dirty, lazy, dishonest, or homicidal, and sometimes all four. Although the story opens in Cyprus in 1946, multiple flashbacks provide the reader with hideous scenes of pogroms in Russia and death camps in Germany and Poland.

Curiously, though, the primary villains of Uris’s novel are not Arabs, Russians, nor Nazis, but the British. British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin comes in for particularly harsh treatment (the novel mixes historical figures such as Bevin with its fictional characters). Much of this is fair. In 1917, via the Balfour Declaration, the British government had come out in support of a Jewish state in Palestine. But when large numbers of Jewish refugees fled Europe for Palestine after World War II, they found their efforts to reach the Levant thwarted by the British military. Thousands were held in British concentration camps in Cyprus, over the objections of the US, France, and many other British allies (most of whom, it should be noted, were not especially eager to take in many of those refugees themselves).

The reasons for this are many and complex and still debated. But Uris simplifies the matter considerably. He argues that the British were eager for Middle Eastern oil and were thus unwilling to anger Arab leaders in the region by helping to establish a Jewish state, even though many Arab leaders had supported Germany during World War II. As a result, the Jewish characters in Exodus tend to view the British with the kind of hatred they might have directed at the Nazis just a few years earlier.

Undoubtedly, the British government and its military made plenty of mistakes in the Middle East, but Uris tends to treat Britain’s every move as evidence of congenital antisemitism. He does throw a sop every now and then to Arab and British readers. One of his major British characters turns out to be of Jewish heritage (though he hides this fact) and secretly supports the idea of an Israeli state. Likewise, a couple of Uris’s Arab characters turn out to be humane and reasonable individuals, but Uris treats them as exceptions to the general rule: Arabs cannot be trusted.

At one point, Uris praises Islamic culture, but it is the Islamic culture of bygone centuries:

In some Arab lands the Jews were treated with a measure of fairness and near equality. Of course, no Jew could be entirely equal to a Moslem. A thousand years before, when Islam swept the world, Jews had been among the most honored of the Arab citizens. They were court doctors, the philosophers, and the artisans—the top of the Arab society. In the demise of the Arab world that followed the Mongol wars, the demise of the Jews was worse.

But on the whole, kind words about Arabs and the British are hard to find in Exodus. Even while World War II is raging, many of the novel’s Zionists have to be convinced that, between the British and the Nazis, the former are the lesser of the two evils. In part, this is because of the infamous White Paper of 1939, a complicated document that attempted to clarify the British government’s stance on a Jewish homeland in Palestine. But in characteristically breathless fashion, Uris treats it as simply a renunciation of the Balfour Declaration of 1917:

Whitehall and Chatham House and Neville Chamberlain, their Prime Minister and renowned appeaser, shocked the world with their pronouncement. The British Government issued a White Paper on the eve of World War II shutting off immigration to the frantic German Jews and stopping Jewish land buying [in Palestine]. The appeasers of Munich who had sold Spain and Czechoslovakia down the river had done the same to the Jews of Palestine. … The Yishuv [the community of Jews living in Mandatory Palestine pre-1948] was rocked by the White Paper, the most staggering single blow they had ever received. On the eve of war, the British were sealing in the German Jews.

Uris uses the phrase “sold down the river” several times, suggesting that he modelled Exodus after Uncle Tom’s Cabin more than Gone With the Wind. When trying to talk a fellow Jew into fighting alongside the British, one character expends more vitriol on the British and the Arabs than on the Nazis: “Even as the British blockade our coast against desperate people…even as the British create a ghetto inside their army with our boys…even as they have sold us out with the White Paper…even as the Yishuv puts its heart and soul into the war while the Arabs sit like vultures waiting to pounce…even with all this the British are the lesser of our enemies and we must fight with them.” (All the ellipses are Uris’s.)

When the novel was first published, it was widely praised by Israelis, as well as by many Americans, both Jew and gentile alike. Critics more sympathetic to Britain and to the Arab nations found it wanting. Today, the book is denounced even by many Israelis. On the occasion of the novel’s 55th anniversary, in the fall of 2013, a writer for the Open University of Israel magazine wrote:

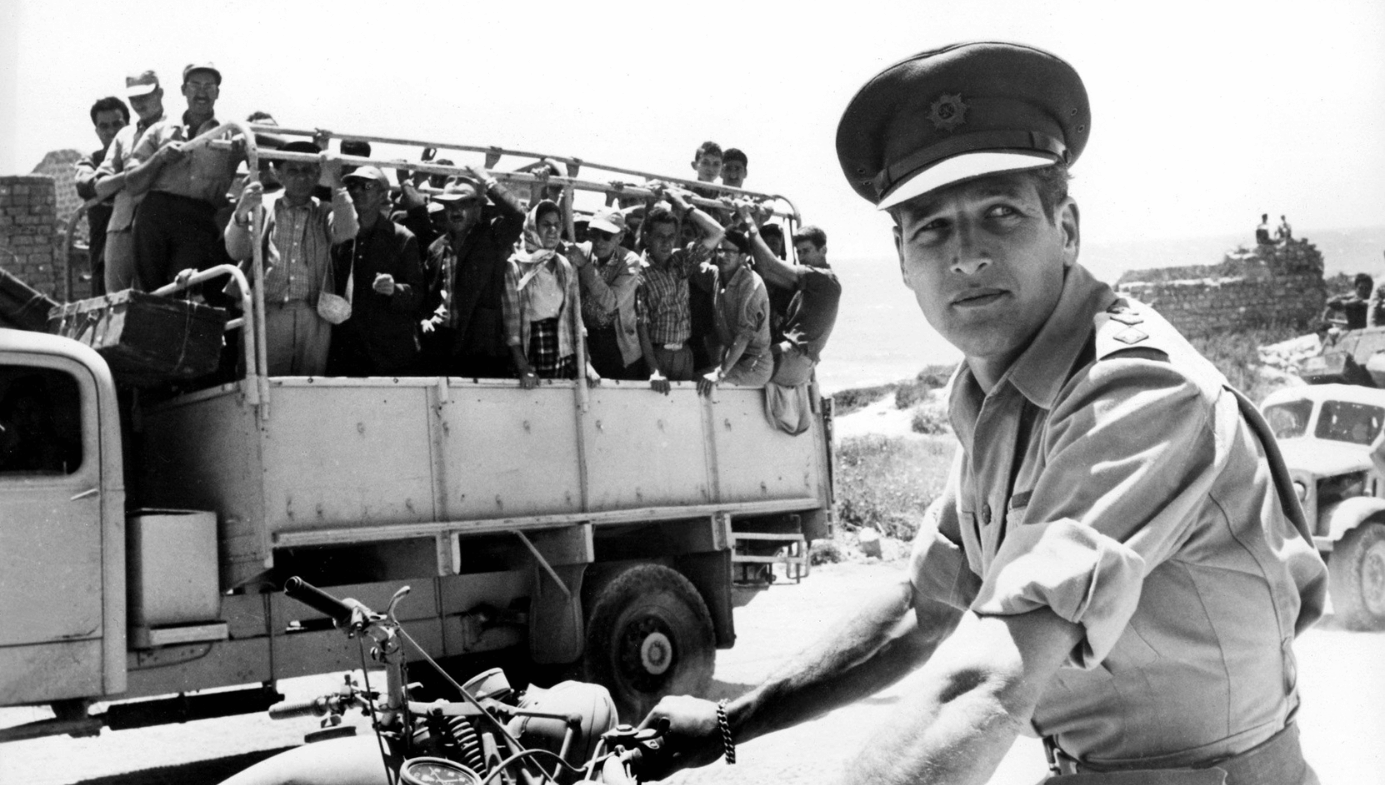

Erase just about whatever you remember from the Leon Uris book, “Exodus” and the eponymous movie made by Otto Preminger with handsome Paul Newman as the hero. Just about none of it is true. Sure, there was a boat by the name [of Exodus], and yes there were Jewish refugees aboard it, who eventually made their way to Palestine, but the rest has little to do with historical facts.

(The novel is a sweeping epic about all aspects of the birth of modern Israel. Otto Preminger’s film focuses almost exclusively on one part of the novel, a fictional retelling of the story of the immigrant ship christened Exodus 1947. People who know the story only through the film, which seems to be the case with the above magazine writer, often mistakenly assert that the novel is primarily a tale of the immigrant ship, which is not the case. The immigrant voyages—there are several of them in the novel—account for only about a fifth of Uris’s tale.)

Historians disagree about which real-life Israeli was the basis for the hero of the novel, Ari Ben Canaan (played by Newman in the film). Some believe the model was Israeli military leader Moshe Dayan. Some say it was Israeli paramilitary soldier Yehuda Arazi. Others maintain it was Israeli intelligence officer Yossi Harel. Writing for the Guardian in 2007, journalist Linda Grant suggested another possible model:

He is 83-year-old Ike Aronowitz, former captain of the illegal immigrant ship Exodus. Who would recognise him? He is known to the world in an entirely different incarnation: as the blond, blue-eyed Paul Newman, who played Aronowitz in Otto Preminger's 1960 film Exodus, based on Leon Uris's blockbuster novel of the same name.

In an interview conducted by Ruthie Blum Liebowitz for the Jerusalem Post, Aronowitz expressed nothing but disdain for Uris’s skills as a historian:

Did Leon Uris interview you prior to writing the book for the details you remember?

Yes he did, in 1956.

What emerged from that interview?

I told him that he was a very gifted writer, but not a historian, and therefore it shouldn't be he writing the history of the Exodus.

How did he react when you said that?

He was very offended. But, of course, I turned out to be right, because afterwards, he wrote a very good novel, but it had nothing to do with reality. Exodus, shmexodus.

Was it completely inaccurate?

I'm telling you, it had nothing to do with reality—not because of my own story, but because of the situation as a whole.

Factual or not, Exodus was clearly conceived as a work of pro-Israel agitprop. And on that level, it was wildly successful. According to Wikipedia:

Whatever the genesis of the work, it initiated a new sympathy for the newly established State of Israel. The book has been widely praised as successful propaganda for Israel. Uris acknowledged writing from a pro-Israel perspective after the book's publication, stating that: “I set out to tell a story of Israel. I am definitely biased. I am definitely pro-Jewish,” and the then-Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion remarked that: "as a piece of propaganda, it’s the greatest thing ever written about Israel.”

Be that as it may, critics were correct to point out that the novel is also wildly inaccurate and even inflammatory at times. Consider, for instance, what Uris writes about the SS Patria, another immigrant ship bound for Palestine:

Two battered steamers reached Palestine with two thousand refugees and the British quickly ordered them transferred to the Patria for exile to Mauritius, an island east of Africa. The Patria sank off Palestine’s shores in sight of Haifa, and hundreds of refugees drowned.

In fact, the SS Patria was sunk by members of the Haganah, a Zionist paramilitary organization, who planted a bomb in the ship’s hull and then detonated it. The ship sank with 1,800 mostly Jewish refugees aboard. Of that number, 267 were killed and another 172 injured. Responsibility for the sinking of the Patria was finally revealed in 1957—a full year before the publication of Exodus—but Uris implied that the British were responsible.

Even worse is Uris’s retelling of the 1946 terrorist bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. The bombing was carried out by members of the Irgun, a more radical Zionist paramilitary organization, which Uris chose to rename the Maccabees for some reason. Irgun’s leader at the time was Menachem Begin, who would later become Israel’s sixth Prime Minister. Here’s what Uris has to say about the bombing:

Finally, the British Foreign Minister burst forth with an anti-Jewish tirade and proclaimed all further immigration stopped. The answer to this came from the Maccabees. The British had their main headquarters in the right wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. … A dozen Maccabees, dressed as Arabs, delivered several dozen enormous milk cans to the basement of the hotel. The milk cans were placed under the right wing of the hotel beneath British headquarters. The cans were filled with dynamite. They set the timing devices, cleared the area, and phoned the British a warning to get out of the building. The British scoffed at the idea. This time the Maccabees were playing a prank. They merely wanted to make fools of the British. Surely they would not dare attack British headquarters!

In a few minutes there was a blast heard across the breadth of Palestine. The right wing of the King David Hotel was blown to smithereens!

That is where Uris’s account ends. He doesn’t mention that the attack murdered 91 people and injured 46. Forty-one of the dead were Arabs, most of whom were hotel employees. Twenty-eight were British, mostly government workers—typists, messengers, and so on. The blast also killed 17 Jews, mostly innocent hotel visitors or workers. Although Menachem Begin and other members of Irgun always insisted that the British were given a warning 25 minutes in advance of the explosion, these warnings were not issued to anyone in authority. In any case, five of the dead were bystanders outside the building. The warnings wouldn’t have done them any good.

Throughout the novel, Uris puts the most positive possible spin on the actions of the Zionists, while portraying any sort of response from the British or the Arabs as acts of terror. This is unfortunate, because along with all the mis- and dis-information contained in the novel, it also contains a great deal of relatively uncontroversial history. He provides moving accounts of the suffering of Jews during the Russian pogroms of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and he delivers harrowing accounts of life inside a Nazi concentration camp.

But then he reports that, when the Nazis ordered all the Jews of Denmark to wear a yellow star identifying them as Jews, brave King Christian X of Denmark chose to wear a star himself, in solidarity with his Jewish countrymen. Uris didn’t invent this myth, but he seems to have been happy to repeat it, if only to make the British look like cowards in comparison with the Danes. Christian did, indeed, show courage in defending his country’s Jews against the Nazis, but he never wore the yellow star.

One of the people offended by the way Uris played with historical truth was a Polish doctor named Wladislaw Dering. In the original edition of the book, Uris accused Dering of having performed 17,000 unnecessary sterilization surgeries on Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz. Dering, though not a Jew, was himself a prisoner at Auschwitz. He had been a member of a Polish resistance group fighting the Nazis when he was captured and sent to Auschwitz in 1942. After the war, he was detained by the British as a possible war criminal. But he was eventually released, after which he returned to the practice of medicine. Dering didn’t discover that he was mentioned in Exodus until 1964, but when he did he took immediate legal action against Uris, suing him for libel in Great Britain.

The trial became a media sensation. It dragged on for 19 days, during which time many former prisoners at Auschwitz testified both for and against the doctor. As it turned out, surgical operations were carefully recorded in a logbook at Auschwitz, and that logbook had somehow managed to survive the war. Eventually, it was established that Dering had performed 130 unnecessary sterilization procedures on both Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz, often using little or no anesthesia. Dering claimed that the Nazis would have killed him had he not performed those surgeries, but other doctors who had been imprisoned at Auschwitz testified that they had refused to perform unnecessary surgeries and had not been seriously punished. Dering’s obedience, meanwhile, had been rewarded with special privileges.

In the end, the court sided with Dering, but awarded him only a halfpenny in damages and ordered him to pay £20,000 in court costs, an amount equal to about half a million dollars today if adjusted for inflation. The verdict was an acknowledgement that Uris had wildly inflated the number of unnecessary surgeries, but the miniscule damages, and the fact that Dering was forced to pay both his own and Uris’s court costs, signaled to the general public that Dering had, indeed, done the Nazis’ bidding at Auschwitz and been well rewarded for it.

After the trial, Dering’s reputation was in tatters and his finances were ruined. Ironically, he was misidentified in the first edition of Exodus as Dr. Wladislaw Dehring. Dering believed that Uris had intentionally added the “h” to his surname to make it sound more German. As a result of the lawsuit, Uris’s publisher eliminated any reference to the number of sterilizations Dering had performed, but otherwise let the accusation against him stand. The publisher also corrected the spelling of the doctor’s name, so that in every subsequent edition of the book, Dering has been identified accurately, which must have further rankled the penniless physician.

The case was so sensational—some called it the first war-crimes trial of World War II to be held in a British courtroom—that Uris wrote a fictional account of it a few years later called QBVII, after the courtroom in which the case was tried (Queen’s Bench Seven). Published in 1970, QBVII became the sixth best selling book in America that year and was later adapted into a hit TV miniseries, starring Anthony Hopkins as the Dering character.

Though Uris freely spread a lot of misinformation during his career as a novelist, he has also been the victim of misinformation, some of it apparently motivated by antisemitism.

In 2010, Rashid Khalidi, a Professor of Arab Studies at Columbia University, told an audience at the Brooklyn Law School that Exodus had been conceived by a Jewish ad executive in New York City who had been hired to promote the interests of Israel in the United States. “This carefully crafted propaganda was the work of seasoned professionals,” Khalidi claimed. “People like someone you probably never heard of, a man named Edward Gottlieb, for example. He’s one of the founders of the modern public relations industry. There are books about him as a great advertiser. In order to sell the great Israeli state to the American public many, many decades ago, Gottlieb commissioned a successful, young novelist. A man who was a committed Zionist, a fellow with the name of Leon Uris.”

A few weeks later, Khalidi told an audience at the Palestine Center in Washington, DC, “Given that many of the basic ideas about Palestine and Israel held by generations of Americans find their origin either in this trite novel or the equally clichéd movie, Gottlieb’s inspiration to send Leon Uris to Israel may have constituted one of the greatest advertising triumphs of the twentieth century.”

Khalidi didn’t invent this canard about the origins of Exodus. The claim had appeared in at least three anti-Israel books published in the 1990s. But in his 2016 book, The War on Error: Israel, Islam, and the Middle East, historian Martin Kramer thoroughly discredits the story of Edward Gottlieb’s involvement with Exodus, noting that:

In sum, the Gottlieb “commission” never happened. Uris’s biographers dismiss it, Gottlieb’s most knowledgeable associate denies it, and no documents in Uris’s papers or Israeli archives testify to it. Yet it persists in the echo chamber of anti-Israel literature, where it has been copied over and over. In Kathleen Christison’s book, it finally appeared under the imprimatur of a university press (California). In Khalidi’s lectures, it acquired a baroque elaboration, in which Edward Gottlieb emerges as “the father of the American iteration of Zionism” and architect of “one of the greatest advertising triumphs of the twentieth century.”

What is the myth’s appeal? Why is the truth about the genesis of Exodus so difficult to grasp? Why should Khalidi think the Gottlieb story is, in his coy phrase, “worth noting”?

Because if you believe in Zionist mind-control, you must always assume the existence of a secret mover who (as Khalidi said) “you probably never heard of” and who must be a professional expert in deception. This “seasoned” salesman conceives of Exodus as a “gambit” (Khalidi) or a “scheme” (Christison). There is no studio or publisher’s advance, only a “commission,” which qualifies the book as “propaganda”—an “advertising triumph.” In Khalidi’s Brooklyn Law School talk, he added that “the process of selling Israel didn’t stop with Gottlieb. ... It has continued unabated since then.” It was Khalidi’s purpose to cast Exodus, like the case for Israel itself, as a “carefully crafted” sales job by Madison Avenue “madmen.” Through their mediation, Israel has hoodwinked America.

Curiously, the Edward Gottlieb fiction seems to have inspired the sixth episode of the classic TV series Mad Men. In that episode, titled “Babylon,” representatives of the Israeli Ministry of Tourism visit the fictional advertising firm of Sterling Cooper to offer ad man Don Draper (Jon Hamm) and his associates a chance to compete for their business. One of the Israelis hands Draper a hardback copy of Exodus. She tells him that it has been on the bestseller list for two years and is soon to be a major motion picture. “America has a love affair with Israel,” she adds, suggesting that Exodus is at least partially responsible for this.

Draper spends much of the episode wrestling with Uris’s novel, reading it in bed at night and discussing it with his gorgeous wife lying next to him. When she asks him if he likes it, he tells her, “I thought it would have more adventure.” Later, during a brainstorming session with his ad team, he asks them how Israel can attract more American tourists. And then, a second later, he answers his own question: “Maybe they should stop blowing up hotels.” It is never stated outright that a New York ad man might have had anything to do with the genesis of Exodus, but creator Matthew Weiner and his team seem to have at least been aware of the rumors and were riffing on them.

After divorcing his first wife, Leon Uris married the much younger Margery Edwards in 1968. A few months after the wedding, Margery died under mysterious circumstances near the couple’s home in Aspen, Colorado. Several newspapers called it an apparent suicide, and the Aspen Police Department eventually concurred. But in 2016, 13 years after his father’s death, Michael Cady Uris published a memoir called The Uris Trinity, in which he claimed that he and his future stepmother became sexually involved when he was 15 years old and she was 24. The relationship continued even after Margery and Leon married.

According to the memoir, Leon found out about the affair and confronted his wife one snowy night in Aspen outside their secluded mountain home. Prior to confronting Margery, Leon had given his son a beer laced with sleeping powder. Michael suspected that his father was up to something and only pretended to drink the beer. Later, when he heard his father screaming at Margery out in front of the house, Michael grabbed a loaded pistol and went out to protect his lover/stepmother.

The encounter grew even more hostile when Michael appeared and Leon began physically attacking him. Michael claims to have drawn his gun only to have his father disarm him and toss it aside. While the two men struggled, Margery grabbed the gun and ran back toward the house. Freeing himself from his father’s grasp, Michael pursued her. They wrestled over the gun for a short time, firing off one or, possibly, two shots. Afraid he might accidentally kill her, Michael let go of the gun, whereupon Margery placed the barrel in her mouth and pulled the trigger. Eventually, Leon arrived at the scene and staged the matter to make it look as if his wife had run off into the woods behind the house and committed suicide in solitude. Michael stuck to that story for 47 years.

It might well have happened that way, but the scene in Michael’s memoir is filled with dialog so melodramatic it might have come from one of his father’s books. For example: “Look at yourself, the grand manipulator and I am your crowning achievement. I enjoy being Frankenstein’s monster. ... All I ever wanted was to be in your good graces; whatever happened between Margery and me was not part of my plan. But your grand design collapsed. You lost control of me, your wife, and of yourself. You’ve had your failures, Dad, accept it. I’m one of them.”

Shortly thereafter, Leon tells Michael: “Nicely played, Son. Maybe I taught you too well. No matter how much you fight it, you’ll never be a model citizen. You’ll never be like your brother. You are my black rose.” Michael notes that, “Even under such stress, in the snow, in the dark, my father could write his dialog and hurl the crippling words like weapons.”

Somehow, I doubt it. Michael writes believably about his love for Margery and about what an overbearing brute his father could be. I don’t doubt that he had an affair with his stepmother. And I don’t doubt that she killed herself when it appeared she was going to lose both her marriage and her young lover in a nasty divorce action. But the drug-laced beer and the three-way confrontation on a dark and stormy night sounds like it was written with a Hollywood film sale in mind.

A year or so after Margery’s death, Leon Uris got married for the third and final time to photographer Jill Peabody. Like Margery, Jill was about half Leon’s age. The union ended in divorce 18 years later. Although his personal life was filled with messy failures, Uris’s professional life included many noteworthy successes. For all its flaws, Exodus remains the greatest and most enduring of them all.