Books

"I Was Never More Hated Than When I Tried to Be Honest"

Allergic to narrow-mindedness, poor taste, and moral arrogance, Ellison detested any kind of racial essentialism, separatism, and determinism.

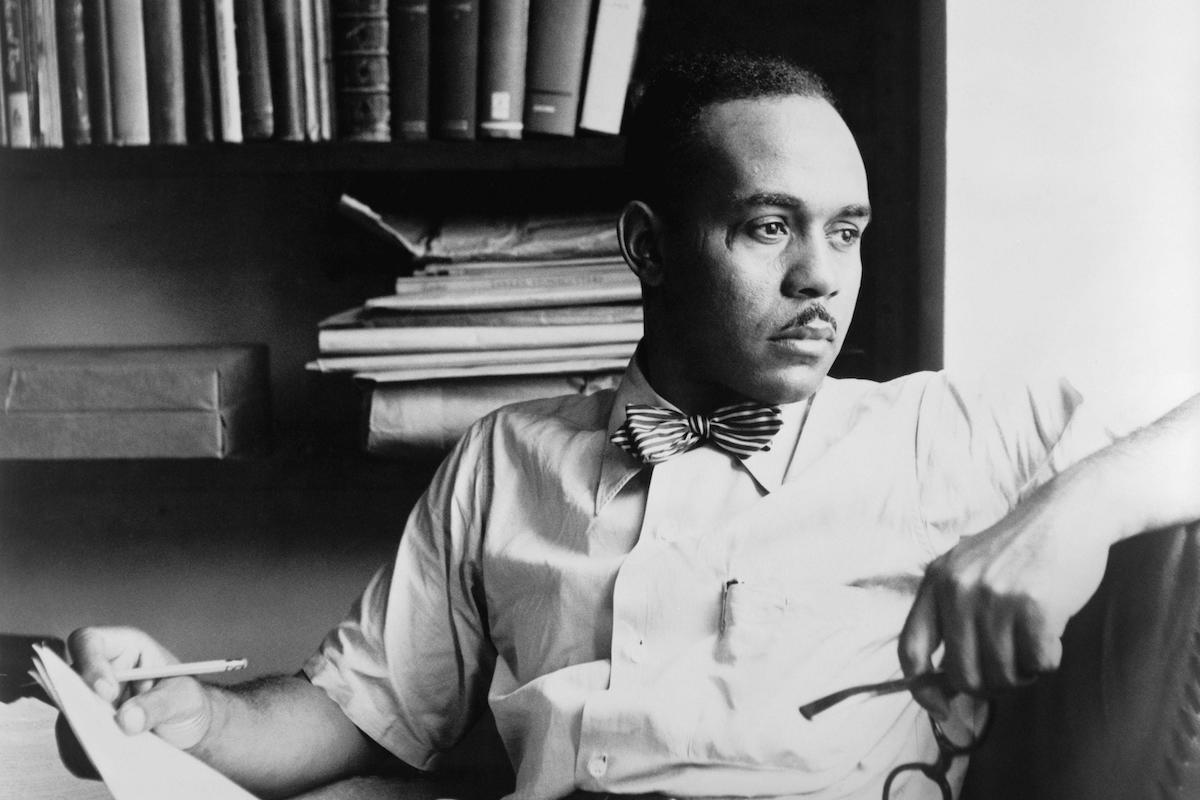

Ralph Ellison, author of the timeless American classic Invisible Man, was among the most commanding black literary voices to emerge in the 20th century. It is a designation he would almost certainly have resented. Ellison didn’t see his work through the prism of his racial identity but as a means of transcending it—using the particulars of his experience to explore human universals. His ambition was not to be a great black writer but to be a great writer who happened to be black, competing in his own mind with Dostoevsky, Melville, Twain. He wanted to “do with black life what Homer did with Greek life” as Clyde Taylor, a professor at NYU, put it. Above all, he wanted blacks to recognize their essential place in the unfolding American story as part of a larger effort to dismantle the artificial racial barriers between disparate ethnic groups that has stalled the evolution of our shared national identity and culture.

Quite unusually, Ellison’s work has resonated across the political spectrum and even pierced the bubble of pop culture. The radically progressive Cornel West once referred to Ellison’s work admiringly as “a brook of fire through which one must pass.” The conservative writer Shelby Steele has cited Ellison as a major influence, saying that he “grants blacks their uniqueness without separating us from the larger culture.” The rapper Mos Def referenced Ellison in the song “Hip Hop” on his award-winning album Black On Both Sides. (“Invisible man, got the whole world watching”), and Kendrick Lamar has done the same. Since its release in 1952, Invisible Man has never gone out of print.

Ellison’s ability to eschew easy categorization helps to explain his unusually wide resonance. Ever elusive, he rejected both Booker T. Washington’s warning to “go slow” on civil rights and the rise of black power sentiment that emerged in its wake. Once a communist, he later came to champion transracial liberal humanism, individual responsibility, multi-ethnic democratic pluralism, cultural nationalism, cosmopolitan universalism, and civil rights traditionalism. He disdained provincial identity politics and rigid sociological interpretations of human life and his politics managed to irritate pretty much everyone at one point or another. Personally, he was ruthlessly ambitious, intensely selfish, stubbornly proud, and constitutionally shy—a complicated man with impossibly high standards, helped by others who identified his many talents but who helped conspicuously few in return. James Baldwin said of Ellison that he “is as angry as anybody can be and still live.” Norman Mailer said that he was “essentially a hateful writer.” There’s some truth to these appraisals: Ellison’s life offers a parable on the steep price of originality.

Allergic to narrow-mindedness, poor taste, and moral arrogance, Ellison detested any kind of racial essentialism, separatism, and determinism. His vision of an America that is in touch with its own fluid ethno-cultural heritage—that is, a country in which whites know they are part-black and blacks know they are part-white—stands in contrast to the prevailing race-conscious sensibilities of modern-day anti-racism that views race and culture through an essentialist framework of victim and oppressor. Similarly, his vision of American culture as a jazz key or a blues chord that anyone can pick up, regardless of who they are or where they come from, runs against orthodox progressivism’s hostility to cultural appropriation. How Ellison came to develop his vision, and at what cost, is the subject of this essay.

Ralph Waldo Ellison was born in Oklahoma City on March 1st, 1913 (although the exact year remains a subject of debate) to Lewis and Ida Ellison, newlyweds attracted to the openness and opportunity to be found in the young state. Established in 1907 without a history of slavery, for a while it was hoped that Oklahoma would allow for a more open racial situation than existed elsewhere across the south after Reconstruction before Jim Crow rules were imposed. The second of three sons, the first of whom died in infancy, Ralph’s ancestral past—some African, some European, some Native American—summoned the region’s historic lineage. In his outstanding 2007 biography, Arnold Rampersad relates that Ellison’s mother presciently warned her son early in his life about the pride he had inherited from his father’s side of the family. His grandfather, “Big Alfred” Ellison, was born a slave in Abbeville, South Carolina before rising to prominence in Republican politics during the Reconstruction era and becoming an important member of the black Union League. When whites took back the region and murdered a friend of his, Alfred defiantly strode down main street insisting, “If you’re going to kill me, you’ll have to kill me right here because I’m not leaving.”1 He lived in Abbeville until his death in 1918.

Ellison’s father, Lewis—known affectionately to his customers as “Mr. Bub”—worked as a small business owner and construction foreman before dying tragically when Ralph was three years old after shards from an ice block pierced his abdomen while he was working. Beyond happy early memories of Lewis (and the buildings Ralph could point to in the city that his father helped to construct), one of the few vestiges of his father’s life passed down to him was a book of poetry by Ralph Waldo Emerson, after whom Ralph had been named. Lewis often read to him, and, as Ralph later discovered, he had secretly hoped that his son would become a poet. A devastating loss, his father’s death would haunt Ellison for the rest of his life and blasted the family into a life of poverty at a stroke.

Even with Jim Crow in place, the sprawling Oklahoma City offered an unusual degree of racial freedom for the time. Its blossoming jazz and blues scenes on Deep Second Street made it a major cultural hotbed and regularly hosted the likes of Duke Ellington and Jimmy Rushing. Ellison once recalled how he and his high school friends would “turn our heads westward to hear Jimmy’s voice soar up the hill and down, as pure and as miraculously unhindered by distance and earthbound things as is the body in youthful dreams of flying.” At eight years old, a friend of his father’s began giving Ellison free lessons on the trumpet and saxophone, and the former would become an obsession for the next 15 years. He and a few friends began reading voraciously at the newly established colored branch of the local library, devouring upscale magazines, countless novels, and headier material like Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. The conditions of his life served as further imaginative inspiration. Ellison has described how he and his friends saw themselves as “renaissance men” and “frontiersmen,” “exploring an idea of human versatility and possibility which went against the barbs or over the palings of almost every fence which those who controlled social and political power had erected to restrict our roles in the life of the country.”2

After a brief stint in Gary, Indiana, following Lewis’s death, the Ellisons moved back to Oklahoma City where the family was helped along by the various members of the local community while Ida cleaned houses in wealthy white neighborhoods. The patriarch of the city’s Randolph clan—a successful black businessman and pioneering educator named Jefferson Davis Randolph in whose house Ralph had been born—stood in as a father figure. Ellison remembers watching in awe as powerful white legislators would solicit legal advice from Randolph. “Why was Randolph considered black,” he remembers thinking, “when he seemed mainly Indian or white and Indian? What was his racial mixture and what made him a Negro?”3 Randolph imparted to the young Ellison a more open conception of American culture that led him to question the relationship between skin color, ethnic origin, and social power.

From an early age, Ellison regularly intermingled with whites, and the stigma of color seemed only to strengthen his pride and sense of the absurd. Following an incident in which the Ellison family was kicked out of a zoo by a white security guard when his mother insisted that they didn’t need the permission of whites, the stupidity of the guard became a family joke.4 But not all relations with whites went poorly. As a child, Ellison befriended a young white boy with a rheumatic heart while collecting cylindrical ice cream cartons with which to make radios, saying of the relationship that “knowing this white boy was a very meaningful experience. It had little to do with the race question, but with our mutual loneliness… Knowing him led me to expect much more of myself and the world.”5 He later wrote that “any feelings of distrust I was to develop towards whites later on were modified by those with whom I had warm relations.”6

But Ellison also recognized that he wanted more from life than his environment would allow, and the pain of his father’s death became increasingly evident in his behavior. Entering the Douglass elementary school for colored children, the first of its kind in Oklahoma City, he oscillated between extreme shyness and violent bouts of rage. He was regularly involved in fights with other students and even, in some cases, adult authority figures. A below average student, given to fantasy more than study, he once sustained a cut over his left eye that resulted in a permanent scar. He fought until he “finally reached the age when I realized that I was strong enough and violent enough to kill somebody in a fit of anger.”7 His poverty-stricken upbringing also made him resentfully class-conscious, and he developed a particular chilliness towards middle-class blacks. Meanwhile, the role of whites in his life took on a more sinister dimension. Although he avoided serious incidents, the apparently god-like power of whites to depersonalize blacks required skillful navigation. “You looked for nuances of voice or for nuances of conduct and interrelationships, and that’s how one survived. And very often you wore a mask, pretending to be what you were not to keep out of trouble.”8

He channeled his energies into music. Mrs. Zelia Breux was then a teacher at Douglass high school and an active promoter of the arts in the community—a member of that elite generation of blacks in the early 20th century that assumed responsibility for the educational development of their people. Under Breux’s tutelage, Ellison became the leader of the freshly inaugurated high school band. While still in and out of trouble, he opened himself up to his teacher and confided in her his dreams and ambitions: “It was Mrs. Breux who introduced me to the basic discipline required of the artist.”9 Graduating high school into the Depression, Ellison worked various jobs as he had done since childhood, including at a clothing store owned by a Jewish family which expanded his curiosity about the diversity of American society. In his Ellison biography, Rampersad writes, “Where, he wondered, did Jews… fit in that murky place in American life where religion met race, and both religion and race merged with class and culture?”10

Torn between the cultural appeal of jazz and the technical prowess of classical music, Ellison applied to the music composition program at Booker T. Washington’s prestigious all-black Tuskegee Institute. Rejected twice, the orchestra’s need for a trumpet player the following year would be his saving grace. Without sufficient resources to get to Tuskegee, he rode freight trains to Alabama and arrived on June 24th, 1933. Drawn to the institution to study under the renowned composer William L. Dawson, he quickly discovered that the dream of Tuskegee was something more closely resembling a nightmare. The institution’s military atmosphere and “up-by-your-bootstraps” rhetoric worked to mask its underlying classism, paternalistic white philanthropy, and the complex machinery of corruption, power, and monied interests that kept the school afloat. The teachers were remote from students, the student body was vastly snobbish, and the classes were more concerned with instilling discipline and developing practical skills than they were with scholarly and artistic achievement. “My trip to Tuskegee,” he later wrote, “was my journey into the heart of darkness. My Kurtz was W.L. Dawson: the artist corrupted by his environment.”11

Worse, his youthful build and handsome face made him a sexual target for some men, a predicament worsened by the fact that he was constantly broke and in need of favors. He routinely wrote home to his mother (who was herself struggling financially) requesting money, clothes, and sometimes food. “It’s a hard go down here,” he wrote Ida, “and when you don’t have money you have to endure too much because the officials and department heads make you do just what they want you to.”12 He told a friend years later, “You should know I was hounded out of college by a homosexual dean of men.” The gap between expectation and reality exposed the lie at the center of Tuskegee: its purpose was not to achieve black excellence but to condition its students for their eventual subordination in a society that took their innate inferiority for granted. Or so Ellison felt at the time (he later softened to Booker). “You must understand,” he wrote to his mother, “that the reputation that this place has and what it really is, are two different things.”13

But if this experience disabused Ellison of certain preconceptions, it also opened new doors. He befriended the school’s librarian, Walter Williams, and began moving away from music in the direction of literature. Accompanied by nightlong, coffee-induced conversations with Williams, he endeavored to read every classic he could get his hands on, from Joyce to Gertrude Stein to T.S. Eliot. The latter’s poem “The Wasteland” left a particularly deep impression on him:

“The Wasteland” seized my mind. I was intrigued by its power to move me while eluding my understanding. Somehow its rhythms were often closer to those of jazz than with those of the negro poets. And even though I could not understand them, its range of elusion was as mixed and varied as that of Louis Armstrong. And thus began my conscious education in literature.

This for Ellison was a revelation: that he could express through writing what he had always wanted to express through music. Now a junior at Tuskegee, he befriended a similarly bright and ambitious freshman, an Alabama native by the name of Albert Murray, who shared his passion for reading. Murray would go on to become a stellar literary and jazz critic, authoring the nonfiction masterpiece The Omni-Americans in which he presciently observed that “The United States is in actuality not a nation of black people and white people. It is a nation of multi-colored people. There are white Americans so to speak and black Americans. But any fool can see that white people are not really white, and black people are not black.” Their friendship, as shown in a selected collection of their correspondence, would prove to be a long and fruitful one for both men.

In the summer of his junior year, Ellison traveled to Harlem in New York City to earn money for the following semester and never returned to Tuskegee as a student. By this time, he had begun to intimate that he would never be a great composer and was hungry for other ventures. He became interested in sculpture while in the city, supporting himself as an assistant in a psychiatrist’s office and later as a laboratory assistant at a paint company, before a chance encounter with the black American poet Langston Hughes in the lobby at the YMCA in Harlem changed his life. A major figure in the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes became a mentor to Ellison and introduced him to someone who would become an even more important figure in his career: Richard Wright, author of the groundbreaking novel Native Son.

Wright was openly associated with the Communist Party in those days, and he introduced Ellison to the world of radical New York politics. One day while pressed for copy, Wright asked Ellison to write a book review for a Marxist magazine he was editing. Wright was so taken with Ellison’s essay that he encouraged him to write a short story, even while he insisted that Ellison was too old to become a writer. That story wouldn’t be published until after his death, but Ellison had found a new outlet for his passions. Over the next few years, he would write dozens of essays, book reviews, and short stories for various magazines before tragedy befell him again. He learned that his mother was dying.

Ellison travelled to Ohio where Ida had been staying with her sister and sold his trumpet—not to pay for her medical expenses but to shore up her insurance policy. Theirs was a complicated relationship, and on some level he probably resented his mother for his father’s absence. But he also loved Ida and, when she died, he and his younger brother Herbert lived in extreme poverty for a period in Dayton Ohio—in mid-winter no less—waiting for the insurance policy to cash in. They got by hunting quail and rabbit in the woods (a skill Ralph had picked up from Hemingway novels) and selling game, sleeping in garages and the homes of family friends and neighbors. It was a dark time, but one that bore fruit. As Rampersad tells it, “Even as he suffered, Ralph was writing fiction. The harsh living conditions, the incoherent processing of grief for his mother, his passion to rise above the shabby in life—all drove him onward… Ralph’s dossier of creative writing had made all of Dayton’s humiliations worthwhile.”14

Returning to New York, Ellison grew weary of the communist scene and increasingly interested in the relationship between psychology, art, and culture. Although slow to disavow the excesses of Stalinism and embrace the war effort, his outlook was rapidly shifting from far-left to center, and from radical socialism to moderate liberalism. Political ideology increasingly struck Ellison as a blunt instrument with which to explore the complexities of the human condition, and he couldn’t shake the feeling that he was being used for partisan purposes. Both he and Richard Wright lost faith in communism over the course of World War II, and Ellison would soon join the merchant marines and work on a ship for a time. Inspired by the novelist Andre Malraux’s Man’s Fate and Days of Wrath, the culture writer Constance Rourke, the literary theorist Kenneth Burke and Burke’s protégé, Stanley Edgar Hyman, who would later befriend Ellison, he had “begun to move away from Marx and the logic of realism, naturalism, and dialectical materialism toward the subtleties and mysteries of myth and symbol, Freudian psychology, and surrealism.”15

Around this time he met his second wife, Fanny McConnell, who would stick with him to the bitter end and support him financially through his early writing. He was editing a black quarterly magazine and won an important literary fellowship—but the makings of a novel had yet to appear. Then, while on sick leave from the merchant marines at a friend’s home in Vermont, he was reading Lord Raglan’s “The Hero” and thinking about “how historical figures take on mythic attributes as they become prominent,” when he stumbled upon the single line that would launch his eventual masterpiece: “I am an invisible man.” The next seven years of his life would be spent in the soul-scorching effort to produce an enduring work of art.

I am an invisible man… I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.

Invisible Man, published in 1952, follows the adventures of an intelligent but unnamed young narrator haunted by his grandfather’s dying words: “Our life is a war and I have been a traitor all my born days, a spy in the enemy’s country ever since I gave up my gun in the Reconstruction.” He sets out to become “a potential Booker T. Washington” through the discipline of humble obeisance. He is childishly naive to the power dynamics all around him and anxious to be an asset to his race in the eyes of whites. In a prophetic dream sequence early on, his grandfather tells him to open an endless series of envelopes until the last one yields an engraved certificate that reads, “To Whom It May Concern: Keep This Nigger Boy Running.”

He wins a scholarship to a prestigious black college after participating in a horrific battle royal for the entertainment of powerful whites, but gets kicked out by its headmaster, the hardened Dr. Bledsoe, because he accidentally reveals too much of black humanity to one of the school’s rich white philanthropists and risks blowing the lid off the whole operation. He travels to New York looking for a job, and is recruited by a secretive political group called The Brotherhood as a public speaker to rally blacks behind their revolutionary cause. He feuds with the local black nationalist figure Ras The Destroyer, and ends up accidentally triggering a bloody race riot in Harlem after his friend is killed by a police officer. Wherever he goes and whatever he does, the people he deals with don’t actually see him as an individual human being but as a means to their own end—an avatar for his group to be dispensed with accordingly. He receives the same treatment from everyone he meets, white or black, progressive or conservative, rich or poor, country or city folk.

Brimming with symbols, rites of passage, taboos, visions, metaphors, and powerful imagery of blackness and whiteness melding together into a composite whole, Invisible Man is ultimately a coming-of-age story about the journey from innocence to self-knowledge, and from invisibility to visibility. The narrator comes to reject the standards that other people have imposed upon him and decides to live against what he sees as the false values of society in a state of active negation. He withdraws into a hole underground to embrace his status as an invisible man, before making the choice at the end of the book to return to society as a mature and self-defined adult who takes responsibility for his existence, creating life’s meaning as he goes along:

When one is invisible he finds such problems as good and evil, honesty and dishonesty, of such shifting shapes that he confuses one with the other, depending upon who happens to be looking through him at the time. Well, now I’ve been trying to look at myself and there’s a risk in it. I was never more hated than when I tried to be honest… I was pulled this way and that for longer than I can remember. And my problem was that I tried to go in everyone’s way but my own. I have also been called one thing and then another while no one really wished to hear what I called myself. So after years of trying to adapt the opinions of others I finally rebelled. I am an invisible man.16

The book is like a beautiful and revelatory acid trip that leaves you more awake than when you started. Ellison touches on perhaps the deepest impulse in all of human life: the need to be seen by others, as experienced by a black country boy moving to the industrial north while trying to stay true to his upbringing; a common experience at the time. He also explores the inextricable link between blacks and whites in the making of American democracy as well as the United States’ national failure to live up to its own transcendent values by recognizing this crucial fact. In this respect, the book represents a profound expression of patriotism. In the epilogue, the narrator describes his situation as one of “infinite possibilities” and says of the country, “Our fate is to become one, and yet many—that is not prophecy, but description.” And despite the unlikely experiences its narrator has undergone, the novel strikes a powerful everyman note in its last line: “And it is this which frightens me: Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” This is the book’s salient theme, and it is one that many contemporary commentators miss: It is not a story about blacks per se, but the shared human struggle to become ourselves, whatever the particulars of our situation happen to be.

Invisible Man was an immediate sensation and it skyrocketed Ellison to literary fame virtually overnight. A near-endless flow of honors and awards followed that no black American had yet experienced. Ellison won the National Book Award in 1953, beating Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, and was granted entry to the most elite spheres of high society. He made regular visits to the White House and developed a close personal friendship with Lyndon B. Johnson. France made him a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and he was awarded multiple presidential medals. He could be found in lavish garb, schmoozing with famous actors, politicians, university deans, and musicians, and he seemed to relish this new lifestyle. He and Fanny bought an apartment in Manhattan and later a house in the Berkshires. More urgently, his book was a major contribution to the ascendent civil rights movement and would come to be regarded as one of the great post-war American novels. Ellison was no longer invisible.

But this newfound fame brought baggage and revealed tensions in Ellison’s personality. Despite all the help he had received from Fanny, his mother, and others over the years, Ellison had dedicated the book to “Ida”—not Ida Ellison but Ida Espen Guggenheimer, a philanthropist who would later disavow Ellison anyway because of his uncharitable depiction of communism in the book. By this point, he had alienated himself from many of the people who facilitated his rise, including Richard Wright and Langston Hughes. Appalled by the cultural turn that followed the civil rights victories, he cut himself off from younger black writers, particularly younger black female writers (he considered Ishmael Reed and Nikki Giovanni unworthy of even reading). He was effectively caught between two phases of a tectonic historical shift, part of that lonely transitional generation of blacks who were loathed by militants but too liberal to be embraced by conservatives.

Ellison became a figure of scorn on college campuses. He rejected what he saw as the incursion of black studies into the sacrosanct realm of higher education, because he saw black American culture as intrinsic to American culture and thought the new Afrocentrism craze laughable. Before a massive audience at Amherst College in Massachusetts during a protracted protest against racism on campus, he insisted to the students that, yes, “Race is a factor in American life. But it is also an excuse for not seeing ourselves as we really are, for not becoming what we thought we would become, for not creating what we promised to create. Let’s stop being victims.”17 As Rampersad observes, this was a tough sell.

One of his literary events was crashed by a young black militant who drove hours from Chicago to tell Ellison that he was “an Uncle Tom, man, you’re a sell-out. You’re a disgrace to your race.” Surprising to many given Ellison’s generally icy demeanor, this visibly hurt him. As one onlooker described that moment, “The whole set of his features was transmuted, the muscles of his body tensed.”18 Visibly controlling his emotions, Ellison responded, “I resent being called an Uncle Tom. You don’t know what you’re talking about. Get on your motorcycle and go back to Chicago and throw some Molotov cocktails. That’s all you’ll ever know about.” Afterwards Ellison broke down, and as he wept on the shoulder of a friend, he repeated, “I’m not a Tom. I’m not a Tom.” The truth was, on some level Ellison really did see himself as a race man, proud of his heritage and enraged by the reluctant attitude held toward civil rights issues by many whites and blacks after the blood-curdling and traitorous betrayal of the post-slavery era during Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow. To now have the younger generation turn around and call him a traitor was too much.

Worse, his second novel, the infamous “work in progress,” never fully came to fruition. For this he is widely considered one of the most “egregious slowpokes” in all of American literary history, in Rampersad’s words. The book’s impending status was a perpetual source of shame and embarrassment for him. The book’s disparate manuscripts were finally scraped together and published after Ellison’s death as Juneteenth, the story of a white-passing racist senator with an African American background re-examining his past after an attempt on his life.

What are we to make of Ellison’s chronic case of writer’s block? He didn’t benefit from the advice and assistance he had enjoyed while writing Invisible Man, particularly from Stanley Edgar Hyman who had passed away in 1970. He also experienced the creeping feeling that much of his work was coming true, with the rise of black power militancy and the political assassinations in the 1960s which eerily echoed his writings. But most of it was probably due to his own ridiculously high artistic standards: He simply wasn’t prepared to write a novel that was worse than Invisible Man. Unsurprisingly, he was never able to accomplish that feat in fiction, but his ensuing nonfiction book Shadow And Act was arguably on par.

Published in 1964, Shadow And Act derived its title from T.S. Elliot’s poem “The Hollow Men” (Between the motion/And the act/Falls the Shadow). It compiled a series of Ellison’s essays, interviews, and speeches from the 1940s to the ’60s, sketching the complex and ultimately symbiotic relationship between black American folk culture—the tragicomic sensibilities of jazz and the blues—and American identity more broadly. It was an attempt to draw together the diverse and kaleidoscopic parts of the national experience and uncover an underlying sensibility that is sufficiently honest and tough to meet the challenges of living in a multi-ethnic democracy. The book also clarifies the mysterious interplay between the individual and their culture, offering a robust rejoinder to the social determinism and racial reductionism applied to blacks in elite intellectual circles. Race is a poor proxy for the subtleties of culture in America and sociological models (what today we might call “structural analysis”) can never fully explain why people do what they do.

In an essay entitled “Twentieth Century Fiction,” Ellison described the unwillingness of American fiction writers of the early 20th century to address the nation’s racial contradictions. That unwillingness, he argued, reflected the cultural and moral decline of the post-Reconstruction period, and he compared Hemingway and Faulkner’s limited portrayal of blacks to the fuller depiction offered by Mark Twain in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Too often what is presented as the American Negro emerges an oversimplified clown, a beast, or an angel. Seldom is he drawn as that sensitively focused process of opposites, of good and evil, of instinct and intellect, of passion and spirituality, which great literary art has projected as the image of man.19

Conversely, the dialogue between Huck and Jim, the former slave Huck befriends, captures something real that expands the reader’s moral sense:

Huck’s relationship to Jim… is that of a humanist; in his relationship to the community he is an individualist. He embodies the two major conflicting drives in 19th century America. And if humanism is man’s basic attitude toward a social order which he accepts, and individualism his basic attitude toward what he rejects, one might say that Twain, by allowing these two attitudes to argue dialectically in his work of art, was as highly moral an artist as he was a believer in democracy.20

Ellison forwards this analysis not as “a plea for white writers to define Negro humanity, but to recognize the broader aspects of their own.”21 It makes one wonder what a great moral leader or story that reveals our collective blindspots would look like today. In “Richard Wright’s Blues,” meanwhile, Ellison describes the spiritual and historical meaning of the blues idiom and its expression in Richard Wright’s violent memoir Black Boy:

The blues is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.22

The blues structure tells a visceral life story from a spiritual distance that allows one to smile in the face of life’s tragedies and develop a more mature attitude toward suffering. Existentially, there is something fundamentally true about the attitude it provokes. Life really is about the interplay of opposites: The broader the scope of suffering we are capable of feeling, the broader the scope of joy. The blues represents a healthy and life-affirming perspective that can only be achieved by accepting what is.

The most powerful essay of the collection, “The World and the Jug,” is a two-part rejoinder to the left-wing intellectual Irving Howe and his contention that Ellison was insufficiently militant in contrast with Richard Wright. In lucid and beautiful prose, Ellison articulates a deeper vision of shared humanity beyond the confines of race. Howe’s focus on structural oppression, he argued, blinded him to the humanity of its supposed victims: “One unfamiliar with what Howe stands for would get the impression that when he looks at a Negro he sees not a human being but an abstract embodiment of living hell.”23

Howe, Ellison contended, had missed the “Negro tradition which teaches one to deflect racial provocation and to master and contain pain. It is a tradition which abhors as obscene any trading on one’s anguish for gain or sympathy; which springs not from a desire to deny the harshness of existence but from a will to deal with it as men at their best have always done.”24 He accused Howe of failing to recognize that culture has a life of its own, independent of the forces that created it. Culture is an organic process of relational evolution that cannot be explained away by the structures of a given social system:

Howe is so committed to a sociological vision of society that he apparently cannot see that whatever the efficiency of segregation as a socio-political arrangement, it has been far from absolute on the level of culture. Southern whites cannot walk, talk, sing, conceive of laws or justice, think of sex, love, the family or freedom without responding to the presence of Negroes.25

Replying to the argument that Ellison would not exist without Richard Wright, he draws from experience to extrapolate a larger message about what it means to be an individual:

I must ask just why it was possible for me to write as I write “only” because Wright released his anger? Can’t I be allowed to release my own? What does Howe know of my acquaintance with violence, or the shape of my courage or the intensity of my anger? I suggest that my credentials are at least as valid as Wright’s… and it is possible that I have lived through and committed even more violence than he… But if you would tell me who I am, at least take the trouble to discover what I have been.26

Similarly, he wrote that “I could escape the reduction imposed by unjust laws and customs, but not that imposed by ideas which defined me as no more than the sum of those laws and customs.”27 But the deepest issue with Howe’s disportionate focus on racial oppression is how it sacrifices a transracial vision of human association in exchange for a paternalistic and infantilizing attitude towards blacks:

Here the basic unity of human experience that assures us of some possibility of empathetic and symbolic identification with those of other backgrounds is blasted in the interest of specious political and philosophical conceits. Prefabricated Negroes are sketched on sheets of paper and superimposed upon the Negro community; then when someone thrusts his head through the page and yells, “Watch out there, Jack, there’s people living under here,” they are shocked and indignant. I am afraid, however, that we will hear much more of such protest as these interpositions continue.28

And indeed we have. What stands out about the essays in Shadow And Act is how relevant they remain to political and cultural debates today.

Ralph Ellison passed away in his apartment on April 16th, 1994, succumbing to pancreatic cancer with Fanny at his bedside. Even as many of his contemporaries veered toward reactionary politics as they got older, he never lost faith in the liberal project. It’s hard to know what he would make of where we are now. On the one hand, there’s no doubt that he would be deeply disturbed by the explosion of racial politics in American life a full 60 years after the civil rights movement. On the other, he would probably take pride in America’s relative and continual success in the ongoing balancing act of diversity. No one ever said it would be easy. “The diversity of American life,” Ellison once wrote, “is often painful, frequently burdensome and always a source of conflict, but in it lies our fate and our hope.”29

He might find it vaguely amusing that, in a country where whiteness is no longer an accurate shorthand for privilege and where the majority of the population will be visibly “nonwhite” in the coming decades, our cultural gatekeepers (many of whom are white) are still complaining about white supremacy. Moreover, the fact that more nonwhite Americans seem to be voting Republican, despite claims that Trump was the embodiment of racism and white supremacism, suggests that race is becoming a less important proxy for politics in American life in unpredictable ways. Progress is not often how we imagine it to be.

History will, I suspect, be kinder to Ellison than his critics. He understood that any genuine anti-racist project must begin from the premise that race has no moral meaning. This he hoped would pave the way for an upcoming generation of liberal, conservative, and progressive humanists who dissented from the prevailing narrative on race issues. The pendulum of American history still swings wildly, and it is the responsibility of mature citizens to keep track of its movements, for we can’t know who we are if we don’t know when we are. We need a moral vision for the country that acknowledges past and present oppression without making a weird religion out of our racial history; one that can, like the blues, accept the reality of suffering without fetishizing it. Ellison gave us the blueprint. He was once asked by an anxious white woman how she ought to behave around blacks. His response was simply, “Be yourself.” A world in which this is taken for granted is one worth striving for.

References:

1 Ralph Ellison: A Biography, p. 8

2 Ibid, p. xiv

3 Ibid. p. 17

4 Ibid. p. 19

5 Shadow And Act p. 5

6 Ibid. p. 12

7 Ralph Ellison: A Biography, p. 18

8 Ibid, p. 34

9 Ibid. p. 26

10 Ibid. p. 39

11 Ibid. p. 63

12 Ibid. p. 61

13 Ibid. p. 67

14 Ibid. p. 104

15 Ibid. p. 163

16 Invisible Man, pp. 572–573

17 Ibid. p. 442

18 Ibid. p. 440

19 Shadow And Act, pp. 25–26

20 Ibid. pp. 33–34

21 Ibid. p. 43

22 Ibid. p. 78

23 Ibid, p. 112

24 Ibid. p. 111

25 Ibid. p. 116

26 Ibid. p. 115

27 Ibid. p. 122

28 Ibid. p. 123

29 Ibid. Pg. 127