Security

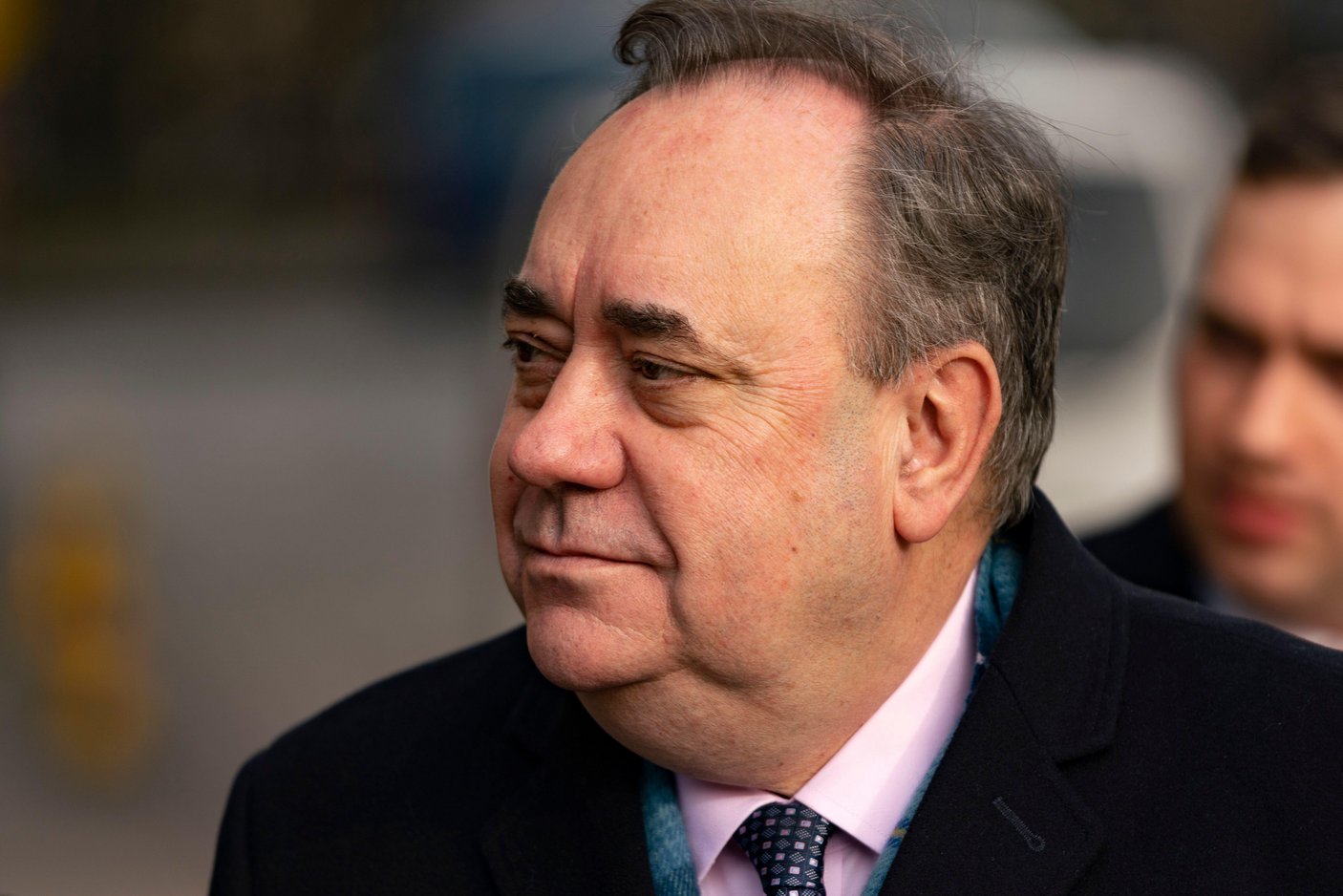

Alex Salmond's Moral Corruption

Salmond simply ignores all comment that he is morally tarnished by continuing to work for RT.

Corruption in government is usually thought of, and investigated, as the appropriation of public funds for private purposes. There are, however, other kinds, and the case of Alex Salmond’s leadership displays two of these vividly. One is the menacing nature of his rule and personal conduct while leader of the Scottish National Party and First Minister. The other is the propagandistic extremes to which his hatred of Britain has driven him.

Salmond led the Scottish National Party from 1990 to 2000, before relinquishing the post to his deputy, John Swinney, for four years. When Swinney failed to sustain the party’s momentum, Salmond returned to lead it again in 2004. Three years later, when the SNP won the Scottish parliamentary elections, Salmond took the post of First Minister. Since then, his party has dominated Scots politics, reducing the once hegemonic Scottish Labour Party to third place behind the Scottish Conservative Party, itself a distant second. Salmond resigned in 2014, having failed to convince Scots to vote for independence in a referendum that same year. But the SNP still enjoys a majority in the Scottish parliament, and the support of the Scottish Green Party. Of the 59 seats for Scottish MPs in the Westminster parliament, the SNP has 47.

But electoral success has provided cover for personal malfeasance. During the 18th century, Scots economist Adam Smith sketched a framework for understanding political actors like the former First Minister. In his 1759 work Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith wrote that “the propriety of our moral sentiments is never so apt to be corrupted as when the indulgent and partial spectator is at hand, while the indifferent and impartial one is at a great distance.” Salmond in power had many indulgent and partial spectators—in Scotland and beyond, especially in the English far-Left; in his party and in the parliament; and in his government and among the civil servants who administered its business. Those critics who were “indifferent and impartial” were dismissed or attacked by aggressive nationalist netizens.

In 2019, Salmond was charged with 14 offences against 10 women, a mixture of civil servants and SNP officials. The charges were one attempted rape, one attempt to rape, 10 sexual assaults, and two indecent assaults. On March 23rd, a jury of eight women and five men found Salmond not guilty on all charges save one, on which they agreed a verdict of “not proven.” In Scots law, this result means, in effect, that the jury thinks the accused may be guilty, but that there is insufficient proof to justify conviction.

In a statement after the trial, Salmond said that when the coronavirus epidemic subsided, he would demand a full inquiry into the case, which his supporters say was confected by his enemies within the party, led by First Minister and Salmond’s former deputy, Nicola Sturgeon. A season of internecine war is confidently predicted as soon as normal political life can be decently resumed. Salmond walked from the court a free man; even the “not proven” verdict leaves no stain on his innocence. Nevertheless, the trial revealed an administration that, under Salmond’s leadership, was bullying, frightening, and unchecked.

Brian Wilson, a Scottish Office minister during the years of New Labour government wrote in the Scotsman on March 27th that:

Salmond ran a regime based on bombast and bullying in which all lines which should separate politicians from civil servants were abandoned. It was an ethos which permeated every corner of Scottish life. Challenge it and you feared for your job or funding or prospects of patronage. Seek to expose it and the phone would soon ring, early in the morning or late at night. The cadre had its enforcers. The civil service needed a leader who would stand up to Salmond. Instead, it had Sir Peter Housden who, on arrival as a cast-out from Whitehall, found refuge in becoming a cheerleader, no questions asked.

The women plaintiffs, who were not named in court and cannot be named now, issued a statement on March 29th, saying they were “devastated” by the judgement. They wrote that:

We want to send a strong and indisputable message that such behaviours should not be tolerated—by any person, in any position, under any circumstances.

Many of us did speak up at the time of our incidents but were faced with procedures that could not deal with complaints against such a powerful figure. Others were silenced by fear of repercussions. It was our hope, as individuals, that through coming forward at this time we could achieve justice and enact change.

We remain firm in our belief that coming forward to report our experiences and concerns was the right thing to do. But it is clear we alone cannot achieve the change we seek.

In a lucid column for the Times the same day, the commentator Alex Massie wrote that “it took some courage for many of the women involved in this case to come forward with allegations. Declaring, in effect, ‘This was my story about the most powerful man in the country. Make of it what you will,’ takes some bravery, not least since doing so invites pitiless scrutiny of your own actions. No wonder so many of the complainers confessed to feeling embarrassed or mortified, or in some sense all but ashamed; no wonder they said they did all they could to bury their experiences, the better to move on and pretend nothing had happened.”

Susan Dalgetty, a journalist and former communications advisor to Jack McConnell, Labour First Minister from 2001 to 2007, wrote in the Scotsman on March 27th of her induction into governmental staff work by the then Permanent Secretary, who told her that “My door is always open… Any problems, any behaviour that makes you uncomfortable, any unreasonable requests, come straight to me.” She added that “it is clear that Alex Salmond regarded the ministerial code with the same cavalier disrespect he had for many of the female civil servants and advisers who were unlucky enough to come into his orbit.”

Dalgetty and Wilson will probably be branded as biased political opponents—former functionaries for a Scottish Labour Party which the SNP has all but destroyed. Less easily so dismissed is Gordon Jackson, Salmond’s main defence lawyer, Scotland’s most senior QC and Dean of the Faculty of Advocates. On March 29th, the Sunday Times reported that Jackson, in conversation on a train from Edinburgh to Glasgow, had been videoed by a fellow passenger as saying that “I don’t know much about senior politicians, but he [Salmond] was quite an objectionable bully to work with… I think he was a nasty person to work for… a nightmare to work for.” The report says that he “appears to say” that Salmond could be seen as “a sex pest, but he’s not charged with that.” He also named two of the women who brought the charges, and spoke of one “in disparaging terms.” In a follow-up report in the Times, Jackson denied calling Salmond a “sex pest” and has referred the incident to the Scottish Legal Complaints Commission.

The anonymous women may or may not be alone when the Salmond affair returns to life once the coronavirus crisis recedes, although it is likely to have a subterranean existence from now on. Salmond has powerful backers in the party, such as the SNP MP Joanna Cherry QC, the Western Isles MP Angus McNeil, and the commentator Kenny MacAskill. Cherry is seeking the party nomination for Edinburgh Central, the Scottish parliament seat presently occupied by former Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson, who is expected to stand down at the next election, due in May 2021. She is opposed in the fight for the nomination by Angus Robertson, a former leader (2007 – 2017) of the SNP group in Westminster. Robertson is a strong supporter of Nicola Sturgeon, and the two contenders illuminate the main split in the party, which can be expected to widen.

The strong support of Cherry, McNeil, and MacAskill is surprising from leading members of a party which had prided itself on fidelity to human and civil rights, and correct behaviour in public office. The sharpest criticism of Salmond’s attitudes in power came from his former speechwriter, Alex Bell, son of Dr Colin Bell, a former vice chairman of the SNP and later rector of Aberdeen University. Alex has some form in this: He has been a constant critic of SNP economic and financial policies, writing in an essay in 2014 that “the idea that you could have a Scotland with high public spending, low taxes, a stable economy, and reasonable government debt… is deluded.” He remains, however, a supporter of its policy of independence.

In his regular column in the (Dundee) Courier, Bell called his former boss “sleazy” and “a creep,” and judges that “Salmond is driven by a core insecurity which is compensated for by a determination to defeat all comers… he will not step back. He’d rather win the argument than be right. Though the two may be confused in his mind.” Since that is the case, he will attempt to reveal that there was a conspiracy in the SNP leadership, run by Sturgeon and her circle to reveal him as a sexual predator, a project which has now failed.

Judged innocent of these charges, in part through Jackson’s inspired defending, Salmond nevertheless stands morally culpable in his present employment. He began presenting a weekly show in November 2017, broadcast on the Russian channel RT on Thursdays. He frequently uses it to showcase Scots nationalist figures: One transmitted on March 5th, a little before his trial began, featured MacAskill discussing a new book, and the former SNP MP and economist George Kerevan.

RT, which promotes itself as telling the truth other channels avoid or are forbidden to broadcast, is part of the large Russian disinformation system. As Pema Levy wrote in the US magazine Mother Jones in October last year:

Propaganda outlets RT and Sputnik which target Americans with English language content, provide a clear view of Russian messaging on the Ukraine scandal… they present a picture of a propaganda machine working to exonerate Trump, condemn former Vice President Joe Biden, and spread doubt about the trustworthiness of American government. The particulars of the Ukraine scandal make a natural fit for the Kremlin’s playbook for destabilising Western democracies: sowing distrust of authority and turning corruption into a “both sides” problem, encouraging citizens to resign themselves to grift and propaganda.

The attempted, and nearly successful poisoning of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in March 2018 has popped up from time to time on RT, at first to be rubbished as an attempt by the government of the then PM Theresa May to unjustly tarnish Russia. The channel reported the charge made by Maria Zakharova, the spokeswoman for the Russian foreign ministry, who suggested that it was a “false flag” event staged by the British intelligence services. More recently, it has, with weary worldliness, suggested that it’s best to “rebuild ties and move on.”

Promotion to stardom on RT requires a strong stomach. Eva Bartlett, a Canadian journalist who is a featured commentator on the channel, is used to show that Russia is seeking to bring the civil war in Syria to a humane end, and to dismiss Western journalism and investigations as lies. A recent report on the UN-mandated International Commission of Inquiry into the Syrian Arab Republic is presented as part of “deliberate disinformation that is halting the eradication of terrorism in Idlib.” On March 2nd, the New York Times reported, quoting the results of a UN panel of inquiry, that Russian fighter aircraft had engaged in “indiscriminate attacks” on Idlib, causing at least 43 deaths.

Salmond simply ignores all comment that he is morally tarnished by continuing to work for RT. Russia invaded and claimed sovereignty over the Ukrainian province of Crimea in late February, 2014. A few days later, Salmond (at this time, still First Minister) said in an interview that he admired “certain aspects” of the Russian leader, including “returning confidence” to his country, and praised his “effectiveness.” His RT salary—said to be substantial, but not revealed—is paid by a Russian state which sees the UK as one of its main opponents, and which—as elsewhere—it seeks to destabilise by manipulating its politics. In that sense, its aims coincide with Salmond’s.

Most commentators, including those who know him well, believe Salmond is set on revenge. Alex Bell’s view is that he is driven by his own insecurity into doubling down on his threats, and will not be deterred by what damage that may do to the SNP. Remarkably, he still has support—perhaps even majority support—in the Scottish National Party. Remarkably, since a successful campaign on his part would mean the replacement of Sturgeon by one of his proxies, or even by himself. And that would mean the replacement of someone broadly decent with someone manifestly indecent. Salmond’s blindness to his own gross faults of leadership, and the hatred which leads him to embrace—and receive a good wage from—the UK’s enemies, should prohibit him from again influencing, or even commanding, the politics of Scotland in the coming decade. But we can’t be sure they will.