COVID-19 Updates

COVID-19 Science Update for March 26th: Five Trends Shaping Medium-Term Policy

Even if a COVID-19 vaccine were invented tomorrow (it won’t be), our experience with the virus shows how underprepared we are for this kind of public-health emergency.

This article constitutes the March 26th, 2020 entry in the daily Quillette series COVID-19 UPDATES. Please report needed corrections to [email protected].

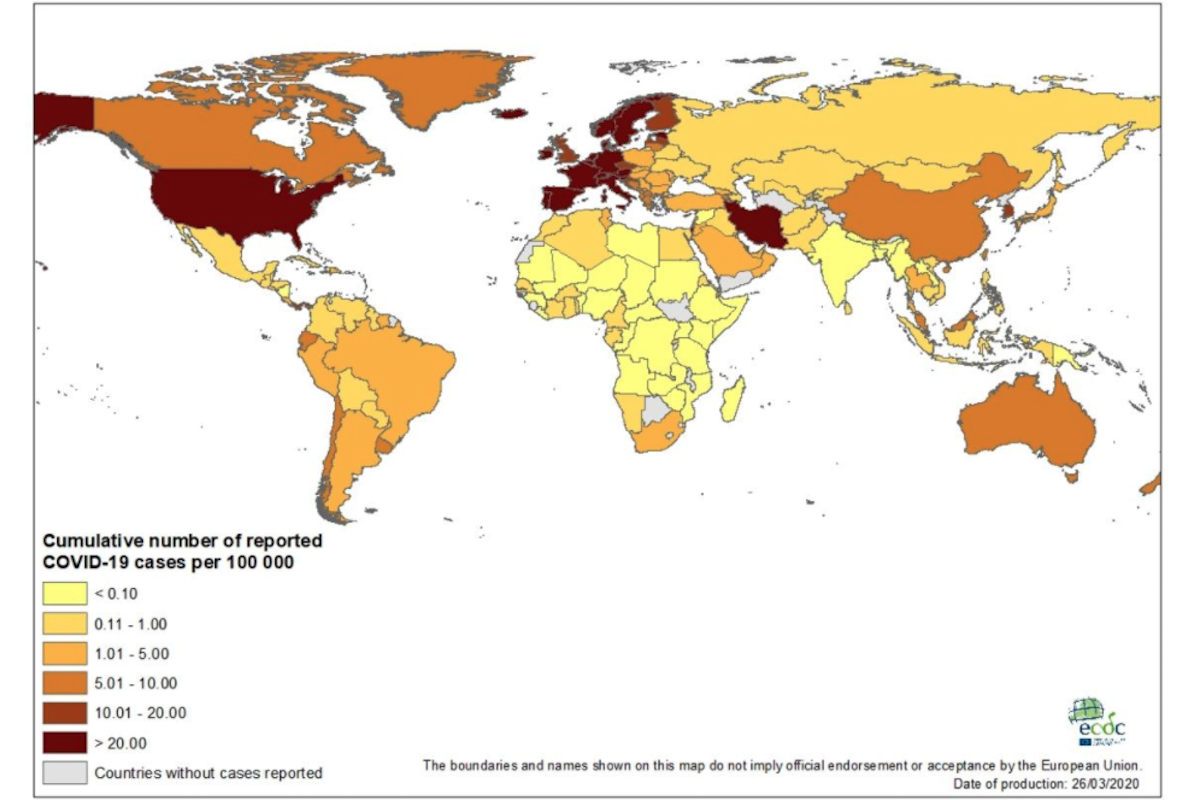

Until today, these updates have begun with a rundown of the latest global data for COVID-19 published at Our World in Data (OWD). As of this writing on Thursday morning, however, the March 26th numbers have not yet been published at OWD. (However, for those interested, there do seem to be recent updates at the website of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, whose reports have formed the statistical basis for OWD daily tallies since March 18th.)

So I will skip the daily rundown of new numbers and proceed directly to the thematic focus of today’s update: a broad-stroke, point-form summary of some of the policies that, even at this early stage, seem likely to inform our global response to COVID-19. Until now, the focus was almost exclusively on the short-term response to the pandemic. But now that social and economic lockdowns in affected countries have somewhat dampened the exponential spread of the disease, there is more latitude for discussion of medium- and long-term solutions.

In the material that follows, I describe five emerging ideas that seem especially important.