recent

It's Time for Sweden to Admit Explosions Are a National Emergency

Sweden has experienced a sharp rise in explosions in recent years, predominantly related to conflicts between warring criminal gangs.

The bomb exploded shortly after 9 a.m. Friday in a blast that ripped through two apartment buildings and could be heard for miles. Twenty-five people suffered cuts and bruises and 250 apartments were damaged. A nearby kindergarten was evacuated. Hospitals jumped into disaster mode. Photos from the scene show rows of demolished balconies and shattered windows. It was ”absolutely incredible” that no one was severely injured, a police spokesperson said.

It is the kind of news we usually associate with war zones, but this bombing took place in Linköping, a peaceful university town in southern Sweden. Remarkably, it was not the only explosion in the country that day; another, seemingly unrelated, blast was reported in a parking lot in the city of Gothenburg earlier in the morning. Three explosions have been reported in Malmö since Tuesday morning. As of this writing, no arrests have been made.

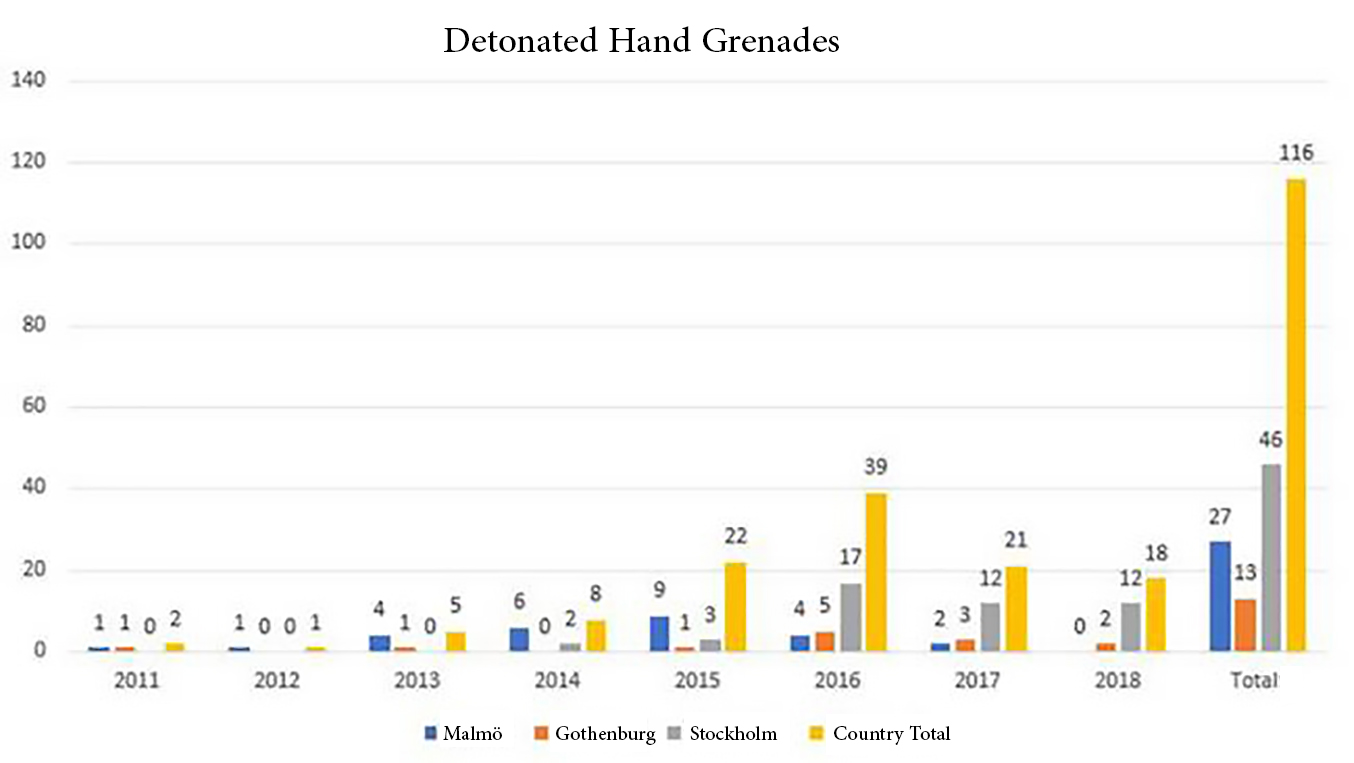

Sweden has experienced a sharp rise in explosions in recent years, predominantly related to conflicts between warring criminal gangs. The use of explosives in the Nordic country is now at a level that is unique in the world for a state not at war, according to police. In response, the government issued a first-ever ”amnesty for explosives” in the fall of 2018, allowing people in possession of such weapons to hand them over to police with immunity. But this didn’t stem the tide: some 50 explosions were reported in the first three months of 2019 alone—an average of more than one every other day and an increase over the same period in 2018, a year that saw a record number of more than three blasts per week.

While explosives have become a weapon of choice among the country’s gangs, the effects of such violence are hardly confined to criminals. In the past four years, fatalities include a 63-year-old man who unknowingly picked up a hand grenade lying in the street; an 8-year-old boy who was asleep when a hand grenade was thrown into the apartment where he was staying; and a 4-year-old girl killed in a car bombing.

There has been a corresponding marked escalation in gang-related shootings, which increasingly take place in broad daylight. Sweden had 45 deadly shootings in what police refer to as ”criminal environments” last year, which is an increase by a factor of 10 in one generation. In contrast, neighbouring Norway has less than three. Deadly shootings per capita in Sweden are now considerably higher than the European average. And systematic witness intimidation, paired with a code of silence in the country’s socio-economically weak immigrant areas, has made this type of crime difficult for the Swedish legal system to tackle.

The rise in gang violence and other types of crime—including sexual offenses and a wave of robberies against children—has had far-reaching implications for Swedish society. In a country which boasts ”the world’s first feminist government,” a third of young women now report feeling unsafe going out at night. A recent survey in the country’s three largest cities showed that safety is now the main priority for Swedes who are looking to buy homes. Crime emerged as a top priority among voters ahead of the election to the European Parliament in May.

According to the prevailing ideology of the Swedish political establishment, this wave of violence, which is baffling to many European neighbours, should not be happening. A longstanding cornerstone of the country’s political conversation dictates that crime must be understood in socio-economic terms, and that welfare provisions are a cure-all against violence and social unrest. Yet Sweden is one of Europe’s most generous welfare states.

Instead of seeking refuge in ideological wishful thinking, the Swedish government should focus on reforming a criminal justice system that was built for a more peaceful society. To name but one issue: young criminals receive remarkably soft sentences. For example, a 16-year-old convicted of an execution-style killing at a Stockholm pizza restaurant in 2018 was sentenced to three years in institutional care for young people. The country also has one of the smallest police forces per capita in the EU.

Before any specific issues can be addressed the Swedish government must acknowledge the severity of the matter. In the past few years, the rise in violent crime in Sweden has attracted growing attention from international media. How has the Swedish government responded? By launching an elaborate PR campaign for foreign audiences that plays down the challenges—especially those in the country’s immigrant areas. Nothing will change if the government continues to respond to the reality in the streets with cynical rhetorical spin.