Sweden's Sexual Assault Crisis Presents a Feminist Paradox

Such levels of gang violence are without parallel in Sweden’s modern history. And with police busy dealing with gang murders and shootings, rape victims wait for justice.

Sweden prides itself on being a beacon of feminism. It has the most generous parental leave in the developed world, providing for 18 months off work, 15 of which can be used by fathers as paternity leave. A quarter of the paid parental leave is indeed used by men, and this is too little according to the Swedish government, which has made it a political priority to get fathers to stay at home longer with their children.

Sweden has never ranked lower than four in The Global Gender Gap Report, which has measured equality in economics, politics, education, and health for the World Economic Forum since 2006. Of all members of Parliament, 44 percent are women, compared to 19 percent of the United States Congress. Nearly two-thirds of all university degrees are awarded to women. Its government boasts that it is the “first feminist government” in the world, averring that gender equality is central to its priorities in decision-making and resource allocation.

But while Swedish women rank among the most equal in the world, they increasingly fear for their physical safety on the streets. Reported sex crimes increased by 61 percent between 2007 and 2016. Meanwhile a rise in gang violence among men–the number of victims injured by gunshots increased by 50 percent between 2004 and 2016–indirectly affects the safety of women. Police admit that rape cases are piling up without being investigated because resources are being drained by gang violence and shootings.

In June, a 12-year-old girl in the small town of Stenungsund reported that she had been dragged into a public restroom and raped by an older boy. Six weeks later the girl had still not been questioned by the police. Even though she believed she had identified the perpetrator, the police had yet to pay him a visit.

“We have so many similar cases,” a spokeswoman of the local police told the Swedish public television channel SVT on September 12, “and there are so few of us, that we simply don’t have the time.” She continued: “We have rape victims three years old,” and even their cases await investigation. Torgny Söderberg, head of the investigation section at the Stockholm police, confirmed the problem on SVT, acknowledging that homicides and attempted homicides draw resources away from rape investigations. “It’s hard to explain why rape cases are piling up awaiting investigation, but the other crimes are even more serious. We are forced to choose between two evils.”

In August of 2016, a woman reported that she had been victim of a gang rape involving ten men in Fittja outside Stockholm. Several suspects were identified early on through forensic evidence and yet it took almost a year until any arrests were made. “I work with rape cases daily, and this is one of the worst rape cases I’ve ever seen,” the victim’s lawyer, Elisabeth Massi-Fritz, told me. “My client has been subject to immense, psychological trauma that will remain with her for the rest of her life. It was nothing short of torture.” And yet, the suspects walked the streets for months before the police found the time to make arrests.

“Unfortunately, the police were too busy and lacked the resources to work the case thoroughly until this spring. Then a number of people were arrested in June,” explained the prosecutor, Markus Hankkio. Ten suspects have now been identified, and the trial will likely begin in October. Over a year after the suspected gang rape, police are now admitting that the same men may have committed more rapes while the police were too busy to investigate this crime, and they are urging other victims to come forward.

Another infamous case in the city of Uppsala became known as the ”Snapchat rape.” Two men filmed their rape of a young girl in real time and then uploaded the video clip to the Snapchat app. Another girl saw the clip, saved it and told her mother, who then alerted the police. It was two months before she was contacted by investigators. “It was terrible, because what you saw in that film, it was the most disgusting thing I’ve ever seen. And that it was so widely spread, and then that they didn’t get arrested,” the mother told SVT. The two suspects were at long last arrested and convicted of rape, but recent statistics show that this is a rare exception to the norm in Sweden. In 2016, only eleven percent of reported rapes were prosecuted, a decrease from twenty percent in 2014.

For more than a decade, the prevailing perception in Sweden has been that rapes and other sex crimes have not become more frequent in spite of data that suggest the contrary. Instead, rising numbers of reported rapes have been dismissed as an effect of a broadened legal definition in 2005 and 2013, and an increased propensity among women to report crimes. Paradoxically, growing rape numbers have thus been used as proof of Swedish gender equality.

There are, however, reasons to think that there may indeed be a real increase in sex crime. While precise numbers are hard to come by, surveys of victims indicate that the share of women in Sweden stating that they have been victims of sex crime has grown rapidly. Self-reported sex crimes doubled between 2012 and 2015, from 1.4 to 3 percent of the female population. The number of women reporting that they feel unsafe in their own neighborhood has increased to almost one in three—an “alarming” development according to The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brå), a government agency.

Previous studies (by now more than a decade old) have shown a large overrepresentation of immigrants, particularly from patriarchal societies in the Middle East and North Africa, among the suspects of sex crimes in Sweden. Overrepresentation of immigrants has been even higher when it comes to group rapes, especially with three or more assailants. According to an official study from 1996, immigrant males were 4.5 times as likely as Swedes to commit rape. Immigrants from Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia were particularly overrepresented, being more than 20 times as likely to commit the same crime. In total, 53 percent of rape suspects were either first or second generation immigrants.

A similar study, conducted in 2005, showed an even higher overrepresentation of immigrants among sex crime suspects, by then up to 5.1 times as likely as Swedes to commit rape (see pages 70-77 for a summary in English). In the 2005 study, Brå explained the growing over-representation with reference to demographics and immigration: “[T]he number of people in Sweden belonging to the group of refugees, which have in earlier studies been shown to have an especially high propensity to commit crime, has increased.” It is a plausible hypothesis that the same mechanism is at work now.

During the recent migration crisis, Sweden took in more refugees per capita than any other country in Europe. However, the exact link between sex crimes and immigration is not known, since the Swedish government will not update its statistics, and the data, which are still being collected, have not been made available to the public. In an interview with the Swedish evening tabloid Expressen on February 25, The Minister of Justice, Morgan Johansson, said that the facts are available in the 2005 study, and that no update is necessary.

But since 2005, Sweden has absorbed a large influx of refugees from the overrepresented regions in North Africa and the Middle East. If overrepresentation has not changed dramatically since this last survey, it is reasonable to infer that immigration has contributed to the increase in reported sex crime. The figures may thus actually convey, not a feminist success, but a failure to protect women’s safety.

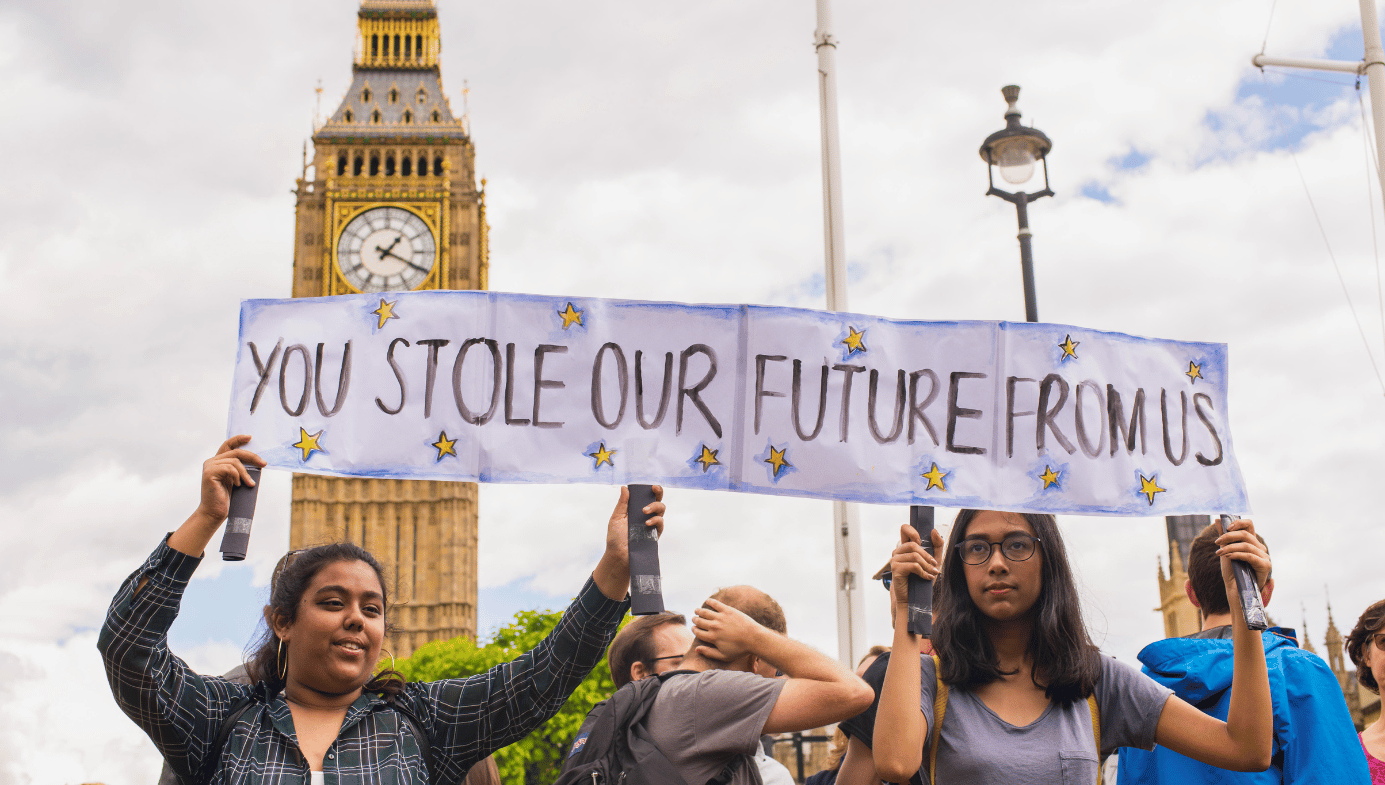

But open discussion of this subject is thwarted by taboos. Xenophobic movements in and outside Sweden use immigrant rapes as a political weapon to generalize about immigrants, which has made it an understandably sensitive topic. This has added to concerns that multiculturalism is tarnished and created a dilemma for Swedish politicians confronted with a choice between progressive orthodoxies about the benefits of multicultural diversity and the feminist duty to ensure female welfare and safety.

Elisabeth Massi-Fritz, the lawyer who represents the victim of the mass rape in Fittja,

vented her frustration in an Instagram post on October 6:

Reported rapes are increasing and on my desk I have many rapes and group rapes. A majority of the suspects that I meet in these cases are of foreign origin. I don’t know if it is a coincidence that I get these cases? To find out, my colleague called Brå to get a hold of correct statistics, in order to spread information and knowledge. I don’t know the figures. Brå doesn’t have them either, because there are no such statistics? I thought I didn’t hear them right. If we are to work preventively and stop rape, it is time to find out who the perpetrators are.

What we do know from a recent police report is that there is a significant overrepresentation of immigrants when it comes to a growing phenomenon of group harassment of women in public spaces, such as music festivals and public swimming pools. “The suspects of crimes carried out by a large group of offenders, in public, were mostly people with foreign citizenship. Regarding crimes reported in public swimming pools, the alleged perpetrators were mainly asylum seeking boys,” according to a report issued by police last spring. Similarly, a study from 2014 shows that, of men suspected of rape outdoors in Stockholm between 2008 and 2009, two-thirds were foreign nationals.

Meanwhile, police are busy dealing with rising gang crime. That the police lack sufficient resources to protect women and are prioritising other types of crime has been the subject of harsh recent criticism by feminists in Sweden. According to official government statistics, shootings have increased, especially in so called areas of “social exclusion” – i.e. immigrant areas marked by high unemployment, welfare dependency, and crime. In these areas, reported shootings as a proportion of population are five times higher than in the rest of Sweden.

A 2014 report by economist Tino Sanandaji shows that the number of areas of social exclusion grew from three in 1990, to more than 180 in 2012. Using a different measure, the Swedish police has identified 61 so-called ”vulnerable areas,” where crimes are significantly affecting the communities. In June, Sweden’s chief-of-police, Dan Eliasson, appealed to both local communities and government authorities to assist the police in dealing with these vulnerable areas. “Help us, help us!” he famously exclaimed at a press conference.

While certain types of crime, such as manslaughter and car theft, have declined over time, recent studies show that Sweden has four to five times as many fatal gun crimes as Norway and Germany. Between 2014 and 2016, police authorities handled more than 100 cases involving hand grenades, an astonishing figure that makes Sweden stand out among countries not at war.

Such levels of gang violence are without parallel in Sweden’s modern history. And with police busy dealing with gang murders and shootings, rape victims wait for justice.