Books

Young Adult Fiction's Online Commissars

Orwell warned that liberty of thought—and literature with it—is endangered when writers in free countries adopt a “totalitarian outlook.”

In the late 1930s, more than 40 years before my family emigrated from the Soviet Union to the United States, my maternal grandmother had a chance to become a published children’s author. She had been writing short stories for her two children, and my grandfather encouraged her to send them to a publisher. To her surprise, she heard from an editor. When she came to see him, he told her he liked the stories very much, except for one problem: they lacked a Soviet spirit. But that, he reassured her, could be easily fixed: for instance, in the story where a young girl who befriends a hedgehog in the woods and promises she’ll always be his friend, she could just say that she gives her word as a Young Pioneer. (The Pioneers were the Soviet mass organization for middle-school-age children.)

My grandma was not a closet anti-Soviet rebel, but she did quietly rebel at being told how and what to write. She thanked the editor, picked up her stories, went home, and never tried to get published again.

In recent years, with the rapidly advancing progressive politicization of American and more generally Western culture, I have often thought of that episode from my family lore. The ideological battles in the Young Adult fiction community, first chronicled a year and a half ago by Kat Rosenfield on New York magazine’s Vulture site, are a particularly obvious parallel.

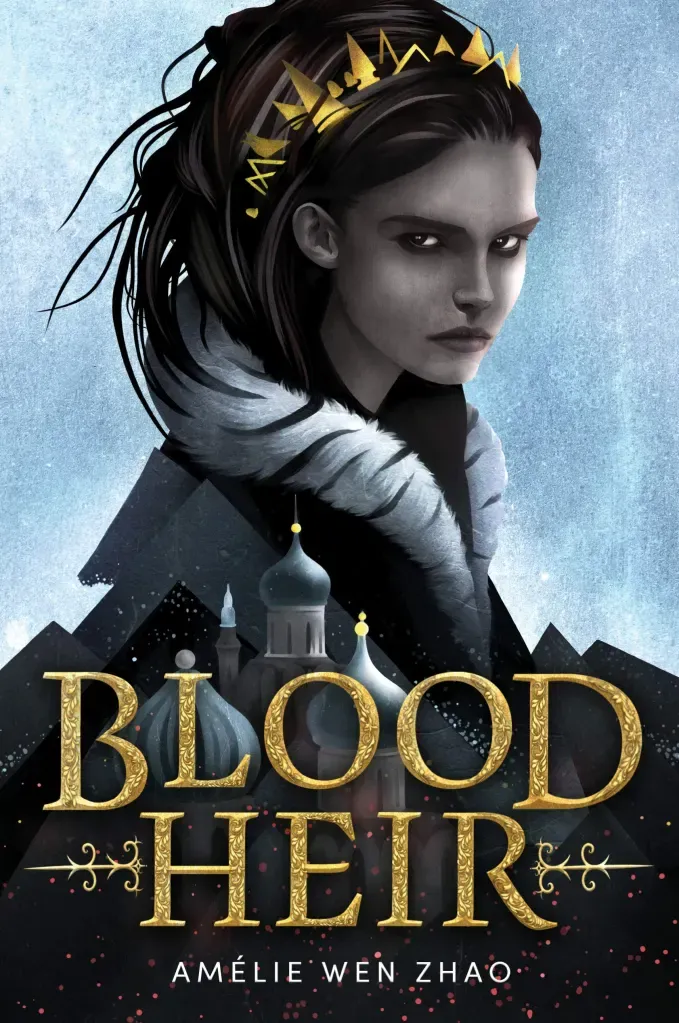

The latest skirmish in that battle is playing itself out right now, and it’s an ugly one. A Chinese-American immigrant, Amélie Wen Zhao, has been bullied and shamed into withdrawing her debut novel, Blood Heir, due for release in June, after a Twitter mob denounced it as “racist” based on snippets from advance review copies. Zhao, who had a three-book deal and had been hailed as an exciting new voice in Young Adult literature, posted an apology for the “pain” her book had caused: