gender

The Uncharted Territories of Medically Transitioning Children

Are we venturing into dragon territory with the transitional therapies increasingly made available to transgender youth?

In medieval times, maps warned adventurers away from unexplored territories with drawings of mythological beasts and a warning that read, “Here be dragons.” Are we venturing into dragon territory with the transitional therapies increasingly made available to transgender youth?

12-16-18

Twelve-sixteen-eighteen isn’t a date, it’s a program developed in Holland for treating children experiencing gender dysphoria, the condition of feeling there is a mismatch between one’s experienced gender and one’s biological sex. When Dr Norman Spack, pediatric endocrinologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, learned of the approach, he decided, “I’m going to do this.” And he did.

In 2007, Dr Spack co-founded the hospital’s Gender Management Service (GeMS), the first clinic in North America devoted to treating transgender children. There, he implemented the 12-16-18 program, which has since been adopted by clinics nationwide. (Dr. Spack did not respond to an interview request.)

Hormones are the tools of the endocrinologist’s trade, which is why, in 1985, a transgender Harvard graduate sought Dr. Spack’s assistance. The patient, born female, had lived as a male named “Mark” throughout his years at Harvard and had been accepted as such. As Dr. Spack recounted in his 2013 TEDx talk, Mark entered his office after graduation and said, “Help me.” He wanted to look like a man, be perceived as a man by those he met or merely passed on the street. And a transition of that nature required hormones.

Dr. Spack had no experience with transgender individuals, but he struck a deal with Mark: “I’ll treat you, if you’ll teach me.”

Over time, more transgender individuals found their way to Spack’s practice, and he did what he could. But hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for transgendered adults can’t reverse most of the physical changes wrought by puberty, so the cosmetic results for individuals transitioning later in life can be unconvincing.

In a 2013 address at Washington University in St. Louis, Dr. Spack explained, “…[E]specially in the case of the male-to-females, they weren’t looking particularly female. They had the height, the hands, the jaw, the brow… If people said ‘men in a skirt,’ a lot of them would have conformed to that.” The 12-16-18 approach offered not a cure for the problem, but a preventive.

Clinicians generally agree that gender dysphoria usually expresses itself early in the life of a child. This point is critical. “Most of our patients declared their gender dysphoria at relatively young ages. This is mostly before age five or six, so clearly gender identity doesn’t just happen,” said Spack.

In roughly 80 percent of affected children, gender dysphoria resolves itself prior to puberty, meaning the children come to accept and feel comfortable with their biological sex. These children are called “desisters.” Most will become gay or lesbian adults.

The remainder, the “persisters,” enter puberty still experiencing an incongruence between the body they have and the one they believe they should. Many clinicians agree that most of these children are permanently transgender. The age at which they consider transgenderism to be fixed is about 12.

Dr. Spack, who theorizes a neurological basis for gender dysphoria, summed up the 12-16-18 approach to treating transgender children: “You can’t change the brain; let’s change the body.”

Puberty is the time of dramatic physical differentiation between females and males. Females develop breasts and hips; males experience a deepening of the voice, the emergence of facial hair, an increase in body mass and height. These normal secondary sex characteristics are precisely those that make it difficult for transgender adults to present an appearance consistent with their experienced identity.

The solution: eliminate puberty.

Drugs that delay puberty, called puberty blockers, have been used for years to treat cases of “precocious puberty,” instances where young children begin to mature sexually. They are now also used off-label in the treatment of children with gender dysphoria.

In essence, administering puberty blockers to transgender children at about age 12 puts them in a biological holding pattern, staving off the development of unwanted sex-related traits that can later be reversed only with cosmetic or surgical procedures, if at all.

This phase of the 12-16-18 program is intended to buy time for additional testing, counseling, and deliberation. The effects of puberty blockers are reversible, though extended use can increase the risk of osteoporosis later in life.

The child who continues transitioning remains on puberty blockers until about the age of 16, though some clinics have lowered it to 14.

In any case, at the end of this step life-changing decisions must be made.

This is the point at which puberty blockers are discontinued and hormones associated with the child’s target gender are introduced. Many of the results are irreversible, the most serious of which is permanent infertility.

A male-to-female teen taking cross-sex hormones will begin to develop breasts, rounded hips, the softer facial features of a female. Also notable is what will not happen: his voice will not deepen, he will not develop a male beard and body hair or male musculature, he will not reach the height he would have as a male.

Depending on the duration of cross-sex hormone therapy, many of these effects may be reversible. Breast development, however, is permanent. A double mastectomy is required to restore the appearance of a male chest.

If anything, the changes in female-to-male teens are more dramatic and less reversible. Among permanent changes are a deepened voice, increased height, and the growth of facial and body hair. Some individuals will develop an Adam’s apple, some male pattern baldness.

Are these choices a young child should make? Many specialists say yes, and the sooner the better, they argue. Clinicians who treat transgender children operate on the conviction that the teens are permanently transgender, so an extended transition process is pointless, even cruel. The current trend, then, is to speed transitioning time, a sort of hormonal hurry-up offense.

Treatment priorities for transgender adolescents are described in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism:

These recommendations place a high value on avoiding the increasing likelihood of an unsatisfactory physical change when secondary sexual characteristics have become manifest and irreversible, as well as a high value on offering the adolescent the experience of the desired gender. These recommendations place a lower value on avoiding potential harm from early hormone therapy [emphasis added].

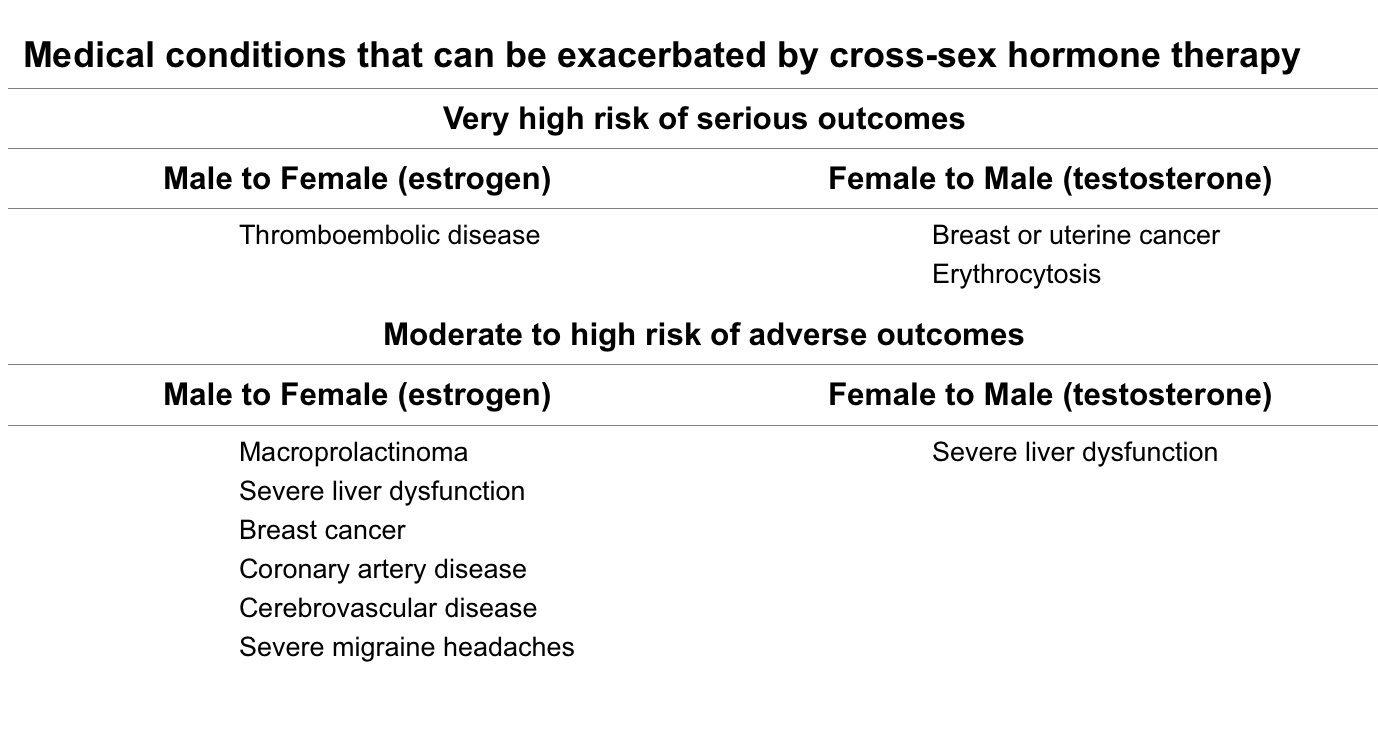

They follow up with the information below:

A year or two after beginning cross-sex hormone therapy, the teen begins the final transitioning phase: surgery.

The final transitioning stage takes place at about age 18 and involves the surgical removal of the patient’s reproductive organs. In biological females, this means the uterus and ovaries; in natal males, the testes. Some teens will also undergo genital reconstruction surgery, which is significantly more successful in male-to-female patients than the reverse.

These surgeries reduce the hormone dosages required to maintain a cross-sex appearance, but do not eliminate the need for lifelong hormone therapy.

In the end, the 12-16-18 program will most often yield young adults whose cosmetic conformation to their target sex is good. Their sexual performance prospects vary depending on a range of factors, including their biological sex and the extent of the surgical reconstruction procedures they opt for—and can afford.

So, is it worth it?

There are too many variables to permit a blanket answer, but a couple of factors have to be considered: First, there are children who from their earliest years believe absolutely that they are in the wrong body. Whatever the source of their condition, their distress is real.

And in a widely quoted statistic, more than 40 percent of transgendered individuals between the ages of 16–25 who receive no treatment will attempt suicide. Some will succeed. Those who don’t are far more likely to die of substance abuse or homicide than the general populace. A clinician’s desire to help is understandable, commendable, humane.

But does it help?

In some cases, apparently yes. In others, maybe. But long-term, no one really knows.

In the Absence of Solid Evidence…

In an editorial note on the website of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, there is this:

Gender-affirming care for transgender youth is a young and rapidly evolving field. In the absence of solid evidence, providers often must rely on the expert opinions of innovators and thought leaders in the field…

In other words, they’re winging it.

They are not alone. Studies on the treatment of children with gender dysphoria are few and inconclusive, a fact masked by the relentlessly upbeat testimonials featured online and in the media.

In September 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a widely quoted study by Dutch researchers titled “Young Adult Psychological Outcome After Puberty Suppression and Gender Reassignment.” On average, the 55 subjects were about 21 years of age and at least one year beyond gender reassignment surgery

The study concluded that the psychological well-being of young adults treated according to the 12-16-18 plan was as good or better than that of their standard-issue peers. CBS news covered the report under the headline: “Transgender teens become happy, healthy young adults.”

However, an April 2018 review, also published by the AAP, sounded a more cautious note:

CONTEXT: Hormonal interventions are being increasingly used to treat young people with gender dysphoria, but their effects in this population have not been systematically reviewed before.

LIMITATIONS: There are few studies in this field and they have all been observational.

CONCLUSIONS: Low-quality evidence suggests that hormonal treatments for transgender adolescents can achieve their intended physical effects, but evidence regarding their psychosocial and cognitive impact are generally lacking.

The British Psychological Society Research Digest, citing the AAP review, concurred:

…[T]he new review reveals how this well-intentioned advice [on early hormonal intervention] is based on extremely limited evidence. When it comes to children, teens and young adults aged under 25, we simply do not yet know much about the psychosocial effects of pubertal suppressors…and further hormonal treatments…).

Research concerns aren’t limited to the effects of hormonal interventions. A study published in the May 2018 edition of the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships considered the social prospects for transgender individuals and learned they are poor: In a sample of 985 respondents, average age 26 (including gay, straight, lesbian, and bisexual/transsexual individuals), 87.5 percent indicated they would not date a transgender person.

Inquiry or Ideology?

In his Washington University address, Dr Norman Spack said, “[Gender identity] will ultimately declare itself with a degree of finality at Tanner 2 puberty (age 9–11 in males, age 10-11.5 in females). Because even Ken Zucker says that Tanner 2 puberty is the defining time.”

Even Ken Zucker.

Based on that statement you might think Ken Zucker is a fringe figure. He isn’t. Dr Kenneth Zucker is the editor-in-chief of Archives of Sexual Behavior and professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He served as chair of the American Psychiatric Association workgroup on Sexual and Gender Identity for the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders (DSM-5).

He was also head of the Child, Youth, and Family Gender Identity Clinic (GIC) in Toronto—was being the operative word.

Dr Zucker’s approach to adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria differs little from that of his peers, but they part company on the treatment of young children.

Current orthodoxy on the care of gender dysphoric children views affirmation of a child’s expressed gender identity as critical. Parents are advised to support a child’s impulse to cross-dress, preference for cross-gender play, desire to adopt a cross-gender name. To do otherwise is seen as transphobic, as suppressing the child’s genuine expression of self.

Dr Zucker and his colleagues at the GIC took a different tack, focusing where appropriate on therapies that encouraged young gender dysphoric children to become comfortable with their biological sex. This approach was viewed by the transgender support community as akin to the discredited conversion practices imposed on homosexuals. They responded by applying pressure in the media and on management, and in 2016 they succeeded in having the GIC shut down.

That’s the Cliff’s Notes version of the story, covered in depth in a 2016 piece by Jesse Singal. But the campaign to discredit Dr Zucker wasn’t an anomaly. Dissenting views on gender dysphoria are routinely suppressed.

On August 16, 2018, a study by Dr Lisa Littman of Brown University was published on PLOS ONE, a site whose stated purpose is “accelerating the publication of peer-reviewed science.” The study raised the possibility that a new form of gender dysphoria has emerged, one that is expressed not early in childhood but that appears suddenly, post-puberty, most often in females with heavy social media exposure who have friends who are also “coming out.” Many of the teens studied also had a history of mental health diagnoses.

The title of the study: “Rapid-onset gender dysphoria in adolescents and young adults: A study of parental reports.”

The pushback: immediate.

On August 25, the Journal of Adolescent Health, in a quickly deleted tweet, weighed in: “Folks, Rapid-Onset Gender Dysphoria (#ROGD) is not a thing.”

On August 27, PLOS ONE published a statement reading in part: “PLOS ONE is aware of the reader concerns raised on the study’s content and methodology.”

The following day Brown University disavowed the study and removed from its website a press release touting the research.

Why the controversy? Because within the transgender support community, rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) is considered a transphobic myth. Many transgender specialists and activists believe that gender dysphoria is immutable. Like Dr Spack, they posit a biological basis for transgenderism, though currently there is no widely accepted evidence for it. A suggestion that gender dysphoria in any form might be a social phenomenon is viewed as false, denigrating, and threatening.

A statement from Bess Marcus, dean of the Brown School of Public Health, read in part:

…[T]he School of Public Health has heard from Brown community members expressing concerns that the conclusions of the study could be used to discredit efforts to support transgender youth and invalidate the perspectives of members of the transgender community.

Some academics expressed legitimate criticism of the study’s methodology. Survey respondents were recruited from websites that serve as forums for the parents of transgender adolescents and young adults. One site describes itself as “a community of parents & others concerned about the medicalization of gender-atypical youth and rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD).” Critics of the study say the respondents were not a valid survey sample because they were biased on the question of transitional therapies.

Not all the responses to Dr Littman’s work were reasoned, however. According to the Economist, Dr Diane Ehrensaft, director of mental health at the UCSF Child and Adolescent Gender Center, wrote “this would be like recruiting from Klan or alt-right sites to demonstrate that blacks really are an inferior race.”

That’s a hard case to make.

On the advice of therapists, some of these parents had initially supported their child’s newly declared transgender status, only later concluding that their child was wrongly being funneled into a treatment scenario involving significant health risks, irreversible physical alterations, and probable social barriers.

In addition, 73 percent of the 212 females described in the study had revealed alternative sexualities—i.e., asexual, bisexual, pansexual, lesbian—to their parents prior to declaring as transgender. That the child’s sexual orientation was already known in most of these households blunts criticism that gender dysphoria only appears “suddenly” in unsupportive homes that discouraged earlier disclosure.

The controversy over ROGD notwithstanding, the phenomenon of children who declare suddenly isn’t new. In his 2013 Washington University address, Dr Spack described the atypical cases that at that time made up 10 percent of the patient population, noting that they did not have a longstanding history of gender dysphoria and could be “extremely obsessive” about their desire to transition:

The kids for whom it happens only recently are the 10 percent who are in the autistic spectrum, mostly Asperger’s… And they’re different because they may have wanted to be a lion two years ago and now they want to be a girl. And it’s tough, and we’re still wrestling with this.

Twelve percent of the adolescents and young adults studied in Dr Littman’s research were reported by parents to have received a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. That may explain some of the cases. As for the others, while transgender specialists discount the social contagion theory, it may fit.

Social Contagion?

Every decade or so there appears a new “It” condition, a previously obscure malady that catches the attention of the media, then the public, and then suddenly seems epidemic. This is particularly true of conditions like gender dysphoria for which there is no laboratory screening test and whose diagnosis relies entirely on a patient’s testimony.

Prior to the 1973 publication of Sybil, for example, fewer than 50 cases of multiple personality disorder were known; by 1998, there were 20,000 reported cases, growing to more than 20 million by some estimates.

Commenting in 2003 on a condition unrelated to gender dysphoria, Dr Carl Elliott wrote:

…Anyone with a rudimentary familiarity with the history of psychiatry cannot help but be struck by the way that mental disorders come and go…This is not simply because people decided to “come out” rather than suffer alone. It is because all mental disorders, even those with biological roots, have a social component…

…Soon the new conditions are discussed in journals and at conferences; clinicians start to diagnose the disorder more and more commonly; the conditions themselves become part of popular discourse and are discussed in support groups, therapy sessions, Internet venues… Patients begin to reinterpret their own psychological histories in light of what they hear, and their behavior changes to match what is expected of people with the condition they believe they have…

(Dr Elliott declined an interview request, stating that he is insufficiently familiar with gender dysphoria issues to comment.)

Though the causes are debatable and likely complex, gender dysphoria clinics are seeing a significant shift in patient demographics. Historically, the sex ratio of “classic” gender dysphoria patients—those declaring in early childhood—has been variously reported as majority natal male or, at some clinics, about a 50-50 split. No longer. Clinics worldwide are reporting a surge in adolescent female referrals, accounting for 72 percent of the 2017–18 patient population at the Gender Identity Service in Great Britain, for example.1

Further, 87 percent of all patient referrals to the Gender Identity Service during that time period were between the ages of 13 and 18, peaking at age 16. In other words, they were declaring a decade or more later than normal for gender dysphoria patients. If you are looking for a cause, social media is a reasonable place to start.

The networking opportunities afforded teens by the internet likely play a major role in fueling the reported ROGD wave. Distressed or curious kids can connect with like-minded peers while staying well under parental radar. You don’t have to look far to find transgender forums where teens swap information on how to con counselors into a gender dysphoria diagnosis or to obtain prescription hormones.

The countless vanity videos featuring attractive transitioning teens can serve as appealing sales pitches to vulnerable adolescents seeking an answer to what ails them.

Young transwomen post photographs of budding breasts. Twenty-something transmen rejoice over the first suggestion of an Adam’s apple. It’s new, it’s edgy, it’s thrilling, and nobody’s asking how it will feel in a decade or two.

Social media is the perfect petri dish in which to culture a trend like rapid-onset gender dysphoria.

Who’s Leading Whom—and Where?

A January 2018 Washington Post piece highlighted the services provided by the UCSF Child and Adolescent Gender Center:

The type of services being requested has also changed. Clinicians say they are no longer taken aback by youths seeking some kind of boutique treatment — often “just a touch of testosterone” for an androgynous, nonbinary identity.

“It’s the children who are now leading us,” said Diane Ehrensaft, the director of mental health for the clinic. “They’re coming in and telling us, ‘I’m no gender.’ Or they’re saying, ‘I identify as gender nonbinary.’ Or ‘I’m a little bit of this and a little bit of that. I’m a unique gender, I’m transgender. I’m a rainbow kid, I’m boy-girl, I’m everything.’”

Dr Ehrensaft is wrong. Children aren’t leading the charge in this field, and limitless gender fluidity isn’t an idea that springs unbidden from the minds of adolescents. These are post-modern gender concepts developed by academics and released into the infosphere where they can be absorbed by kids who are bored, troubled, or seeking new and creative ways to freak out their parents.

The boutique response to adolescent gender games is likely a small part of what the UCSF Child and Adolescent Gender Center does, but that they indulge them at all seems frivolous and unworthy of the children and adults who genuinely suffer. And as the long-term effects of such interventions are unclear, it also seems risky.

Gender dysphoria isn’t new, but the treatment options and the evolving demographics are. Clinicians are in the unenviable position of having to make Solomonic judgments about how best to treat a changing patient population. And given the response by academics and activists to conservative treatment approaches, some practitioners may feel pressured to approve transitional therapies that are safe from professional censure but inappropriate for the patient. They may remember that an Ohio couple lost custody of their child for refusing to authorize hormone therapy, and that Kenneth Zucker’s clinic was shuttered, and that Lisa Littman’s research was sandbagged.

An August 2018 article on Medscape asks, “Caring for Transgender Kids: Is Clinical Practice Outpacing the Science?” Clinicians would do well to consider that question carefully. There may be dragons lurking.

References:

1 https://www.jsm.jsexmed.org/article/S1743-6095(15)30967-X/fulltext