enlightenment

Between Discipline and Chaos

No human institution can ever secure a definitive interpretation of goodness, and it is usually the ones that claim to have done so that betray their own purpose.

“Anyone capable of living outside a city,” wrote Aristotle, “must either be a beast or a god.” Before taking offense or pride in that aphorism, the rural should know that the Greek for “city” here is polis, and the polis of classical Greece was not a city in our sense. It was smaller than a nation, to be sure, but unlike London or Washington, it was a sovereign state. Every human individual, Aristotle is saying, must live within such a group—whether it be a tribe or an empire. To lack such a polis, to live truly alone, would require the independence of a wild animal or the self-sufficiency of a god.

We need groups to survive; we need someone else to do our hunting or growing, someone else to make our clothes and build our houses, someone else to fix our furnace and perform our surgeries. But the polis does more than help us survive. It encompasses the family, the school and the broader culture, all of which shape who we become. Without such groups, and especially the state that orchestrates them all, we cannot reach our potential. Left to ourselves, ironically, we could not become individuals.

But even if Aristotle was right, such groups can also inhibit us, stifling our individuality. This was a common fear of 19th century thinkers, who witnessed the encroaching conformity of modern life: democratization, industrialization, the homogenization of opinion through the distribution of newspapers. John Stuart Mill deplored this insidious pressure. “It practices a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression,” he wrote in On Liberty (1859), “since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself.”

This enslavement began with “a State education,” which Mill called “a mere contrivance for molding people to be exactly like one another.” Once they graduate from basic training, however, they still need to be finished. Their conformity continues into adult life thanks to “an increasing inclination to stretch unduly the powers of society over the individual both by the force of opinion and even by that of legislation.”

Two decades before Mill, Alexis de Tocqueville saw gentle and voluntary subjection as a persistent danger for modern democracies. “After having thus successively taken each member of the community in its powerful grasp and fashioned him at will,” he wrote in Democracy in America (1840), “the supreme power then extends its arm over the whole community.” It softens, bends, and guides citizens by “a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd.” This popular tyranny he dubbed “soft despotism.”

When this subjection has extinguished individuality and eccentricity, when everyone has been “reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals,” only then can they be granted every Enlightenment right and freedom. In other words, democratic citizens are grateful to be paid handsomely in a currency they will never spend.

Two decades after Mill, with the industrial revolution now disrupting the continent, Friedrich Nietzsche turned these English and French prose critiques into the German poetry of Zarathustra (1883): “One must have chaos in one to give birth to a dancing star,” so “the time is coming when man will give birth to no more stars.”

This future time Nietzsche foresaw, an era of social tyranny and soft despotism, would be the time of “the most contemptible man,” the now-famous Last Man. Society will then be perfectly ordered; the last men will look back on the injustices of the past—the public hangings, the sexual misconduct, the offensive jokes—and the smartest of them will declare that “formerly all the world was mad.” Now, “everyone wants the same thing, everyone is the same: whoever thinks otherwise goes voluntarily into the madhouse.” Or at least makes a public apology, loses his job, and disappears from view (for a few months, until everyone has moved on to the next scandal).

Here, then, is a paradox: If Aristotle is right, we need groups, and above all the state, to become who we are; yet if Tocqueville, Mill, and Nietzsche are right, modern life stifles our individuality. Assuming that all four of these thinkers are correct, this essay tries to resolve this paradox. How do we become ourselves, recognizing that we need institutions to do so, while also understanding that modern institutions have been designed to frustrate that very goal? This essay tries to answer that question. To do so, though, we must first understand our precise predicament.

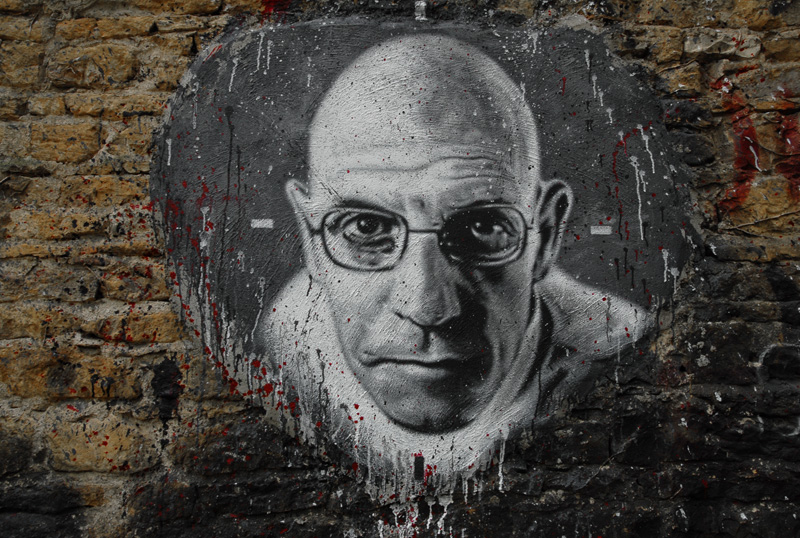

Michel Foucault’s understanding of the Enlightenment provides a powerful explanation. In Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault argued that in the 18th century European societies, and thereby their successors across the globe, began to see themselves as subjects of “discipline.” Before, citizens had to be regulated by force and intimidation to preserve civil order. Now, they were formed and corrected throughout their lives—in schools, hospitals, barracks—so as to be self-regulating. A constant surveillance now afforded maximal control not only of citizens’ external behavior but also of their inner life.

This novelty was clearest to Foucault in Jeremy Bentham’s design for the “Panopticon,” a new sort of prison that put cells in a circle around an observation tower. Because the cells would be backlit by the sun, while the warden remained forever in the dark, he could see them, but they could never see him. They would never know when, or even if, they were being watched. Eventually, there would be no need for a warden. Experiencing years of such surveillance, prisoners would become their own wardens.

Foucault already thought, thanks to the proliferation of institutions such as schools and the explosion of regulations for everyday life, that we moderns live in a sort of panopticon. Had he lived another thirty years, though, he would have enjoyed the perverse pleasure of seeing the 21st century as the climax of his story. Every class now lives a good part of their life online, where the solitude and independence necessary for resistance to soft despotism, social tyranny, and discipline dissolves in a deluge of righteous opprobrium.

Without cultivating leaders to whom such solitude and independence are familiar, whole societies now move in blind unison toward goals barely understood. This is most obvious on Facebook, where circles of friends confirm each other’s biases. It is least evident on Twitter, the wild west of social media, where vicious partisans are so entrenched in their views that even counterpoint can confirm bias. On Facebook we can be driven by the likes of our friends while on Twitter we can be driven by the disdain of our enemies. All the while, we keep supplying corporations (and in some cases political parties) with the daily hauls of data they are using to accumulate powerful knowledge.

According to Foucault, such knowledge is powerful not only because it makes individuals susceptible to discipline; it is powerful especially because it creates the very individuals over whom discipline will exert control. People start to regulate their own thoughts according to the implicit rules of social media. So it comes to pass that every citizen—both poorly educated laborers and highly educated elites, those on the left as well as the right—assume discipline through surveillance, conformity, control, and obedience in a manner so subtle it is considered a natural and inevitable part of civilized life.

Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror elaborates this discipline in several episodes, but especially “Nosedive.” In the not-so-distant world it imagines—already achieved in some ways, exceeded in others, by the Chinese—everyone has a social score, constantly revised according to the ratings everyone is giving each other. These scores are visible immediately through eye-implants, which work for the visual drama of television, but are not necessary for its realization in our present lives. It is enough now that we check our accounts as often as we do. The effect is the same: We regulate ourselves according to the praise or scorn we receive from our online audience. “No herdsman,” spoke Zarathustra, “one herd.”

So we don’t need to be tyrannized by men in jackboots; we are daily disciplining ourselves beyond the wildest fantasies of Bentham and the other Enlightenment thinkers. But it’s not quite enough. Twitter mobs are not satisfied by online derision. Destroying someone’s reputation will never be as pleasing as a drawing and quartering in the town square. To satisfy the mob, then, the punishment must be carried into the meatspace where it will really hurt. Careers must be ruined, the contagion must be expelled, and the punishment must not be limited to the virtual world. The latest instruments of surveillance may be new, but their allure is rooted in primal behaviors. We all feel it, even as we disown its fulfillment. Everything and everyone must be disciplined.

The best illustration of this momentum comes from the place where you would least expect it. Universities are supposed to be havens of free thought and free speech, and yet on many campuses the ideal is under siege. The worst threats do not come from social-justice warriors inspired by postmodern philosophy or conservative snowflakes taking their cues from television demagogues—although each pose their own, very real problems—but instead from the assumptions shared by those on the left and the right.

Adopting Foucault as their patron, more often than not, thinkers on the left—who form the majority of the professoriate in the humanities and social sciences—compromise their resistance to discipline when they become trapped in the view that every human being is but the sum of social categories. If the identity of everyone is determined by the overlapping groups to which she must belong, not by the thoughts she alone thinks, no room remains for her to create herself as a unique individual. Pursuing equality with zeal, these partisans confuse equal outcomes with equal opportunities, and are rarely satisfied unless natural differences have become taboo.

The situation is no better on the right, where embattled thinkers reject fundamental challenges to their views with vague allusions to postmodernism. Pursuing freedom with zeal, they confuse their own circumstances with universal conditions, failing to see how much preparation is required to benefit from freedom. While the dominant left ignores the individual to promote groups, the minority right promotes an “individual” who is really only the projection of one group’s fantasy. The one is the explicit opponent of the individual, the other its covert enemy. As they squabble over largely symbolic gestures, they cooperate with the most dangerous, hidden trends of academic life: Discipline continues unopposed to throttle it.

Every year faculty must conform their teaching and their courses to ever more absurd “rubrics,” “learning outcomes,” and “assessment tools.” These are usually the diktats of administrators, but sometimes celebrated by the faculty themselves.

It’s all a dream (or a nightmare, as the case may be) that the university will serve the bigger social machine. One big cog, driven by the smaller cogs of departments, professors, students—achieving what? The reproduction of the very power it embodies: The meaningless repetition of empty categories of accreditation, promotion, and whatever can be pawned as “education” on hapless students and their parents or loan-officers.

In such an environment, what can you do to nourish individuality? Resist the discipline, or more specifically, resist the Enlightenment version of discipline exposed by Foucault. Insofar as both the right and the left co-operate in the enforcement of this discipline, when it comes to many of the political debates of our time you will find yourself on the outside looking in. As you begin to reject their alternating appeals to surveillance and regulation, moreover, you will have to learn to tolerate chaos.

Not all chaos should be accepted, needless to say, but does its very existence disturb you? Is your first impulse, in the face of chaos and uncertainty, to imagine a rule, an authority, or an institution that could eliminate it? If so, that’s where to apply your efforts—to moderating that impulse. “As wood is the material of the carpenter,” advised Epictetus, “so the subject matter of the art of life is the life of the self.”

In the Black Mirror episode “Arkangel,” a mother who has been terrified by the short disappearance of her wandering toddler has a chip implanted in the girl that will forever reveal her location. Additionally, the mother can view the world through her daughter’s eyes, monitor all her vital signs—knowing when she has sex, gets pregnant, or does drugs—and even suppress any perception that causes her stress. The daughter then grows up without maturing.

The constant surveillance keeps her away from fear and danger, so she never learns in childhood how to handle the little stresses that could teach her how to handle the bigger ones in adult life. Evoking Oedipus Rex, the episode ends with the mother bringing about the violent disappearance she originally hoped to prevent. It was her fear of pain and chaos that fated her daughter’s suffering and disorientation. If only she had been braver, if only she had been able to foresee the foolishness of trying to regulate everything.

Is any discipline capable of accepting a healthy amount of chaos? Is any group compatible with dissent and innovation? Well, why else do universities exist? At a rudimentary level, they train undergraduates in an accumulated body of knowledge. At this level, some fields produce homogeneous intellects. But at all levels in some fields, and at higher-levels in all fields, the point of the training is to produce individuals who will dissent from received doctrines in order to innovate and discover.

In this way, universities function like institutes of art or music, which fail to be more than trade schools unless their students devise something new. Officially that is what universities strive to do, and in many fields they succeed. But in some, where the strictures of administrative discipline are tightening, dissent and thus innovation become increasingly rare. To resist this discipline requires many virtues, but above all the courage to dissent and the wisdom to innovate. Saying no to orthodoxy is not enough; you must also say yes to what you alone can see.

No human institution can ever secure a definitive interpretation of goodness, and it is usually the ones that claim to have done so that betray their own purpose. But neither should human institutions give up on goodness altogether. Those that devote themselves unequivocally to contemplating it will encourage, if not guarantee, the training of individuals wise and courageous enough to resist the condemnation of political partisans. To cultivate wisdom, courage, and the other virtues, universities must reconnect with a premodern model of education, wherein formation of character was a prerequisite for training the intellect.

But as things stand, individuality is blunted just as the 19th century thinkers predicted it would be, and already was. Mill said of the best and brightest of his day that they “dare not follow out any bold, vigorous, independent train of thought, lest it should land them in something which would admit of being considered irreligious or immoral.” And here we are today, most grievously in our universities, where these trains of bold thought are lost when they should instead be followed out to their most ambitious conclusions. In an Academy worthy of the name, our only warden should be the elusive and ineffable Good; our only aim: to give birth to dancing stars.

This essay is adapted from “Disciplining the Individual” by Patrick Lee Miller, which can be read in full here.