Top Stories

Don't Get Fooled Again: The Continuing Necessity of Anti-Communism

The socialist experiment has been run and the results are in: it is a failure—Revolution => Dictatorship => Horror.

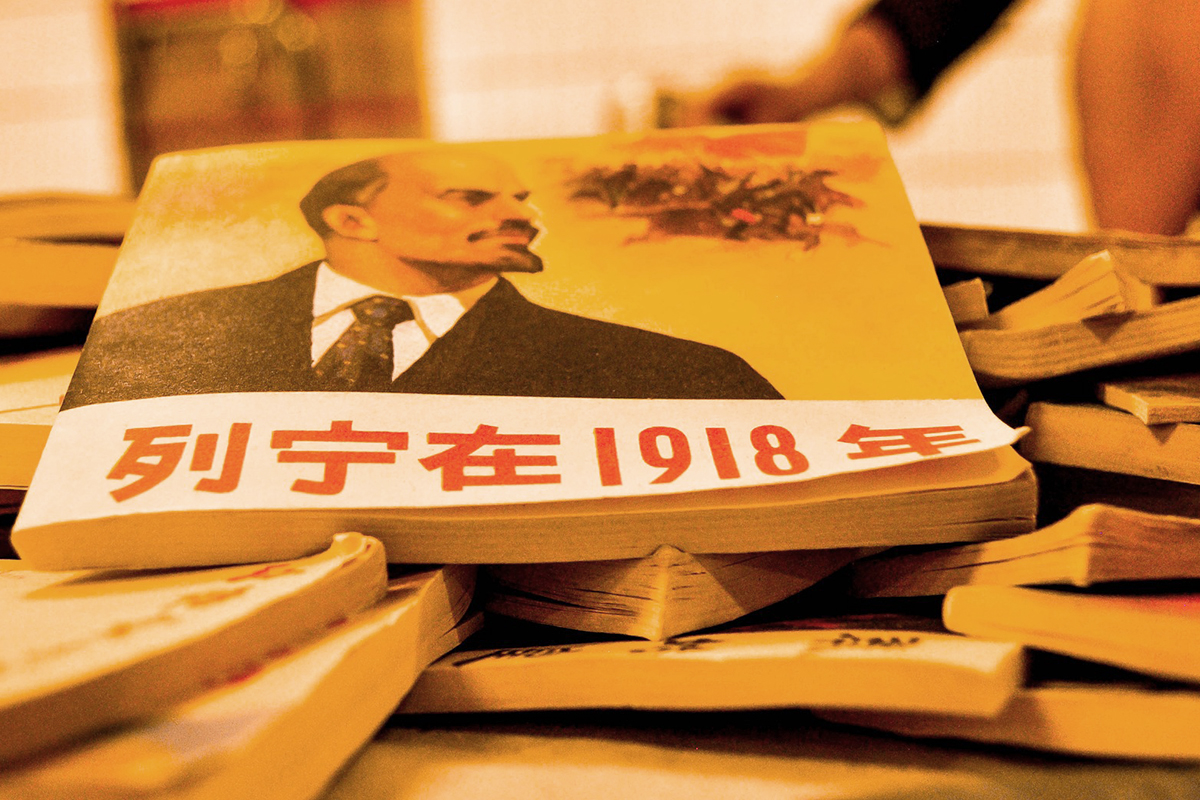

Socialism is having an unprecedented moment in America: opinion polls show its increasing popularity, especially among youths; membership in the Democratic Socialists of America continues to swell; mainstream publications, such as the Washington Post, publish pieces arguing that it is time to give socialism a try; and academics articulate the merits of taking an anti-anti-communist stance. The root cause of each is the same: all people in all times are concerned with flourishing to the greatest extent possible and in darker times the ever-optimistic views of socialism’s proponents have an attractive force not unlike that of the flame to the moth. As history has shown, this attraction is equally dangerous.

Most contemporary socialists—such as Kristen R. Ghodsee and Scott Sehon, in defense of their anti-anti-communism position—do not dismiss the historical crimes of communist states and recognize that “states governed under communist ideology did many bad things.” Instead, they seek to defend Marxist socialism against the charge that it is inherently authoritarian, meaning that all such experiments “will always and inevitably end with the gulag,” and thereby to save the possibility of political “experiments with Marxism” that take a non-authoritarian form. They continue to hold out hope that some version of Marxist politics can deliver on its emancipatory promises.

But are the horrible things that have happened in communist countries the natural conclusion of Marxist ideals? Understanding the connection between the philosophical and political facets of Marxism is the question for both those who would call themselves socialists and those who call themselves anticommunists. On one hand, socialists today attempt to sever the theory of communism from its historical practice to preserve the hopes they see within it; on the other hand, anticommunists understand this historical practice to be inherent to the theory and the hopes of communism to be false. The effort to save communism from its historical record tacitly recognizes that it is worthy of unqualified condemnation if this record (like in the case of Nazism) is the inevitable consequence of its principles—at least we agree on that much!

From the Communist Manifesto we learn that Marxism “may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property.” This principle is the theoretical and practical sine qua non, as well as that which guarantees that every attempt to erect a Marxist system, whether socialist or communist, democratic or totalitarian, will degenerate into an authoritarian nightmare.

This statement is clearly in need of demonstration.

Life, Liberty, and Property

What is private property? In the simplest terms, ownership is the natural right of an individual to use or dispose of something exterior to his or herself in whatever manner he or she wills. This right emerges from the natural right to life in the following manner: The right to life implies the right of self-preservation, that is, the liberty to act in whatever manner is necessary effectively to preserve one’s life. It is not simply mere life that is rightfully preserved; rather, human beings by nature seek healthy, flourishing life. Life implies the freedom to preserve life which implies the right to acquire the means of self-preservation. It is not accidental that John Locke speaks of “life, health, liberty, and possessions” in section 6 of his Second Treatise.

That the right to life is the ultimate foundation of private property is seen in the first and most fundamental act of self-preservation, which is at the same time the original act of appropriation: eating. When a human being eats, he takes something that is nourishing (and thus intrinsically valuable) to all other human beings and, in the process of consuming it, destroys it and transforms it into something devoid of value.

In a pre-political environment prior to the enclosure of the commons, an individual was free to appropriate from nature what he or she needed to survive. In this condition, taking what another had harvested was a violation of the natural law provided there remained enough and as good for those who came after. Because the one who came after could do equally well through his or her own efforts, taking from another merely substituted the other’s labor for one’s own. This substitution makes a slave of the other. The qualification of the natural right to property (i.e., enough and as good) does not limit acquisition from nature—one is free to pick the last remaining apple from the tree to feed oneself. Moreover, that apple still belongs to the one who picked it. But for those who come later, it makes taking from another no longer naturally unjust. Thus, we see that the more fundamental natural right to life can justify violations of the natural right of private property in the pre-political environment. We also see that conditions of natural scarcity will inevitably bring the fundamental rights of individuals into conflict. Hence, as Hobbes observed, the life of man in the state of nature is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Within society, the right to eat a particular item comes from its proper acquisition (i.e., pursuant to the laws), which in most instances means the item was either grown by, purchased by, or gifted to the one who eats it. But this is merely positive or legal right. As in the state of nature, the more fundamental natural right out of which this legal right grows can still trump the legal right when they conflict. This is clearly seen in the cross-cultural tendency to forgive the one who steals out of genuine necessity. Even in society, it is not unjust to take from another when it is truly a matter of life and death. Not unjust, however, is not the same thing as just. And it is still illegal.

But is the private property of the state of nature the same as the private property found in society? Or, does the move from the state of nature to society beg an important question? Possibly. Marxists today distinguish between personal property (apples, jeans, and Kenny Loggins records) and private property (the means of production). While libertarians are famous for asserting that all taxation is theft, socialists similarly argue that all private property is theft and thus they object to enclosure itself as the original theft of what were once common and public resources (see Jacobin magazine’s ABCs of Socialism). For the sake of the argument, let us grant that what is really meant by private property is the means of production—whether land or machine—and that this can be distinguished from personal property. The question is: what justifies the enclosure of the commons? Initially, labor.

The same principle that transformed the apple into the personal property of the one who picked it likewise transforms the land enclosed and cultivated into the private property of the one who labored upon it. If someone invests his or her labor in improving and enclosing a plot of land, sows and cultivates the crop, can anyone else possess an equal let alone better claim to the results? But what about to the land itself? That the land is no longer in a natural state, that it has been transformed according to a plan effected by said individual speaks loudly in favor of its appropriation—who else could possess a better claim to its use in the next season, especially since the act of cultivation is an ongoing process?

The transformation of the land is at the same time its improvement: enclosed and cultivated land yields far more than it did prior to being so enclosed. Such land is intrinsically more valuable and the increase in value is directly attributable to the one who improved it. In its natural state, a plot of land can support one person or one family; improved by human labor directed by a plan, that same plot will support some multiple thereof.

This situation, however, only holds provided there remains wilderness to tame and enclose. Once the final acre of land is enclosed and the requirement of “enough and as good” cannot be satisfied, what happens then? This is a profoundly important question: What will happen when human beings are born into an enclosed world?

Enclosure and the Commons

Marx believed, correctly, that this is precisely the situation into which we are thrown, and that the enclosure of the world makes social revolution inevitable—the have-nots will have no choice but to band together to take from the haves. It’s a matter of survival. It’s not a matter of if, but a matter of when.

Believing that private property inevitably leads to conflict, Marxism seeks to improve the future by correcting this perceived mistake. That is, it jettisons the idea of enclosure and reaffirms the commons. Socialists fail to understand the causal relationship between the enclosure of the commons, the protection of private property, and the near miraculous increase in the fecundity of the environment that has raised the material standard of living for human beings so dramatically. So they seek to pull up stakes and tear down fences in the belief that the productivity found in a state of natural and voluntary social interaction can be equaled, if not surpassed, in the commons—provided we all work together according to the right plan.

And that right there is the problem: socialism requires unanimity. In other words, like the American Founding Fathers, socialists seek to solve the problem of “faction” (Federalist #10). In the first instance, socialism seeks to eliminate the “most common and durable source” of faction: the unequal distribution of property (Federalist #10). Moreover, as Joseph Schwartz and Jason Schulman argue in their essay “Toward Freedom: Democratic Socialist Theory and Practice,” socialism seeks to eliminate to the greatest extent possible those sources of faction that arise from the division of labor “by the rotation of menial tasks, frequent sabbaticals, job retraining, shortening the workweek, and increasing the creativity of ‘leisure’ activity.” And yet, Schwartz and Schulman recognize that “there would be a need for expertise (say, for surgeons and engineers) and job specialization under socialism.” Setting aside the question of whether or not such specialized labor might result in differential rewards and economic inequality (thereby undermining the first effort), that some will hold particular jobs for extended periods of time (even for their entire working lives) will give rise to distinct interests.

Specialization itself raises the connected issue of the “diversity in the faculties of men” (Federalist #10). The fact of human diversity in terms of capabilities, inclinations, opinions, desires, and passions guarantees a diversity of interests in every society, provided this diversity is allowed to express itself. Insofar as the success of collectivist economic arrangements depends upon a uniformity of opinions, passions, and interests with respect to the common economic goal of the system, any member who dissents is a threat to the whole arrangement. Since support for the socialist system must be unanimous (i.e., total), the liberty to develop one’s own capabilities, to follow one’s own inclinations, to express one’s own opinions, and to satisfy one’s own desires must be constrained. Dissent, therefore, merits suspicion, which is why Greengrocers will place a sign declaring “Workers of the World Unite” in the window as a demonstration of conformity.

In other words, because the socialist system cannot give “to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests” (Federalist #10)—because human nature is an insuperable obstacle—socialism must destroy liberty and it must do so totally. This is why coercion and control are necessary components of socialism and why human beings cannot flourish under it (despite being able to do so on the micro-level). The good intentions of socialism run up against the hard limits of human nature and reality. In seeking to overcome these limits, socialism necessarily becomes a totalitarian tyranny. Furthermore, it is the worst kind of tyranny, that of the well-intentioned tyrant who tyrannizes you for your own good and with a clear conscience.

Enclosure and Liberty

Returning to the profoundly important question above: What will happen when human beings are born into an enclosed world? What is the alternative to Marxism?

The short answer is: the road actually taken.

Rather than late-born individuals resorting to violence to provide for themselves, the enclosure of the commons, the development of agriculture, and the subsequent rise of industry opened a cornucopia of opportunity. What we saw was a revolution, just not the bloody variety.

The agricultural revolution depends upon a whole host of supporting innovations, for example, hand tools, horseshoes, and plows, and eventually tractors, threshers, and combines. These developments serve as the basis for industry and result in the rise of cities and industrialization. Moreover, just as in the case of agriculture, tool-making, which begins as an arduous and complicated task completed by hand, is improved by the application of technology. We found better ways to make better tools. Industrialization, which is arming human labor with technology (and includes not only machinery but principles of organization, such as the assembly line), leads to ever greater increases in labor productivity. This is clearly seen, for example, in the decline in agricultural employment: close to 50 percent of people worked in agriculture in 1870, but less than two percent did so by 2008. It is also partially responsible for the decline in manufacturing employment: in 1910, this accounted for about 32.4 percent of jobs, whereas in 2015 it accounted for only 8.7 percent.

Under conditions of freedom, the economy develops and gives rise to new kinds of economic activity and opportunities. At first, agriculture dominated. But gains in productivity freed up human labor for other pursuits. Then industry arose, leading to even more gains in agricultural productivity and accelerating the shift in where people were employed. This revolution in both agriculture and manufacturing led to higher levels of material prosperity. We also became more and more productive as we got better and better at making things. There was more of everything—and it was better! The service sector exploded onto the scene, as someone had to sell all this stuff that was being made by fewer and fewer people. The story culminates (at least for now) in the rise of the knowledge economy and the knowledge worker who finds better ways of doing everything. Each of these economic revolutions was layered upon the ones preceding it, and opened new and diverse opportunities that enabled the diversity in the faculties of human beings to better express itself. It is as if no matter what your talent happens to be, today there is a way to monetize it. None of this was planned. Nor could it have been. And the process continues with no end in sight.

Rather than leading to conflict, the enclosure of the commons, the rise of industry, and the subsequent evolution of the economy led to competition and cooperation—or, another way of saying this, to cooperation in competition. In a system of liberty, human beings are not isolated, atomized individuals. They exist within a network of networks; they are family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, competitors, and citizens. The life of each is individual, familial, social, economic, and political all at the same time. The rich tapestry of existence is woven from these interrelations. While we are thrown into particular circumstances and confront them together, we do so on our own terms. The relations into which we are born need not remain those of our maturity. Born into a particular family in a particular community, we are free to leave these behind, joining together with others (provided they will accept us). Neither the faith of our fathers nor the business of our mothers, must be our own. The important point is that within a system of liberty where association is voluntary, human beings are free to cultivate their nature in ways in which they cannot under any other system.

The Results Are In

In conclusion, socialists claim that overcoming the bourgeois system would usher in a new way of life wherein the free development of each was a condition for the free development of all—Overthrow capitalism => ? => Utopia. Life in this classless society, we are reassured, would be marked by liberty, equality, and solidarity. The appeal of these universally recognized ends not only captured the imagination of those who believe there must be a final political solution to all human ills, it also justified whatever actions were deemed necessary for bringing this situation about. And yet, in each and every instance over the past century, politically empowered socialism has produced a system of servitude, inequality, and suspicion, where the life of a dissenter is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. The socialist experiment has been run and the results are in: it is a failure—Revolution => Dictatorship => Horror. In fact, we need only compare the lives of those who lived in West Germany to those who lived in the East, or those who live in South Korea to those who live in the North, which is a Kingdom of Darkness.

Growing up in an era of unprecedented freedom and prosperity—and living lives that are only possible under such conditions—many Americans of all political stripes simply take for granted the political and economic system bequeathed to them by the dedicated work of their ancestors. Most simply do not understand that prosperity depends upon freedom, that freedom is like water, utterly necessary to flourishing of any and every kind. To push this analogy a bit further, if freedom is like water, then we are like fish swimming within it—and like fish, we pay no mind to the water despite its being necessary to our very existence.

What we do notice, however, is all the dirt that muddies the water. Freedom is messy; it’s filled with prudence and foppery alike; when people have the freedom to choose, they do not always make what others would consider to be the ‘right’ choice. Oblivious to the importance of freedom, many of us are open to the proposals of those who claim it is easy to get rid of the mud by further empowering the state as a means of empowering the individual. Considering only the end, we fail to recognize that the proposed means amount to draining the lake. When one does not recognize the importance of the water, it is all the more difficult to be convinced of the necessity of cleaning rather than discarding it. Anti-communism is the refusal to throw out the water. The next step is to figure out how to clean it.