Education

I’m a Male Teacher Surrounded by Women. But Please Don’t Call Me a Victim of Sexism

My experience shows that sometimes gender discrepancies develop within a professional field for reasons that have little to do with discrimination, and everything to do with personal choice.

The conversation surrounding gender discrepancies in workplaces and universities often focuses on STEM—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—because these are high-paying fields in which women typically lag men in both representation and advancement. There is far less attention paid to similar or greater disparities in other disciplines. Rarely, for instance, does one hear much complaint about lower-status professions such as construction, logging or roofing, all fields where, in the United States, men make up over 96 percent of workers. The pattern is similar in my own country, Canada, and in the wider Western world more generally. In regard to skilled occupations that women dominate—such as accounting, nutrition, pharmacy, physical therapy, psychology, veterinary medicine, social work and nursing—advocacy groups fighting for equal representation tend to fall mute.

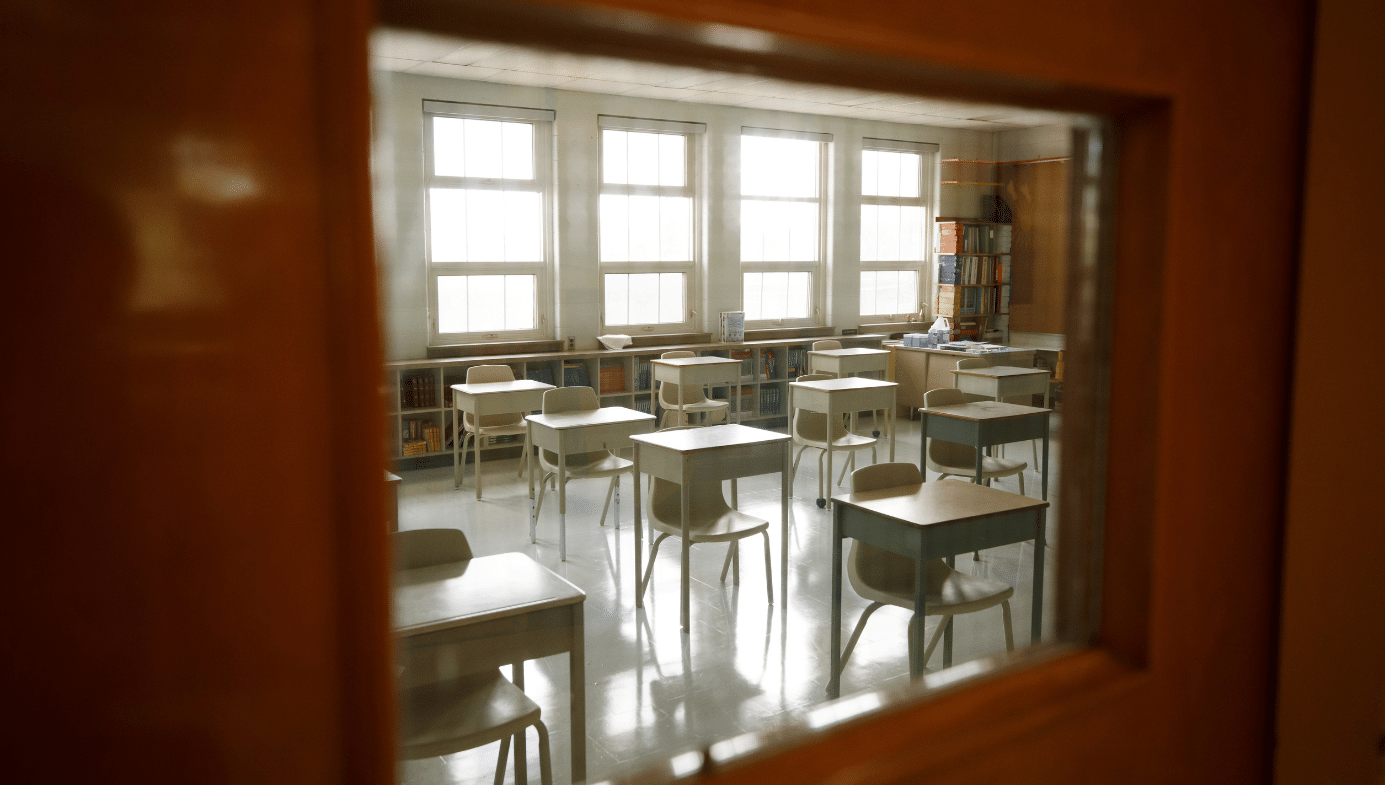

My own field, education, also features a striking gender imbalance. As a man with hopes of becoming a teacher, I am embarking on a career that is overwhelmingly dominated by women. According to Statistics Canada, women make up roughly 60 percent of high school teachers, 84 percent of elementary school teachers, and 97 percent of early childhood educators. A similar trend plays out in all OECD countries. If across-the-board gender parity were the priority of those who fight for equal representation in STEM, surly those same voices would also be militating on behalf of men in education. But this isn’t happening.

The Canadian Teachers Federation, a national trade group that represents teachers, holds an annual Women’s Symposium that “aims to gather women teacher leaders from across the country to study a particular theme or issue which will strengthen the status of women and improve the situation for women within the teaching profession.” Such an event would make sense in a field such as physics or manufacturing, where there really is a relative dearth of women. But in the teaching field, an event like this makes as much sense as a “Men’s Symposium” conducted by air force pilots.

Studies that have been conducted on the lack of female representation in STEM typically concern themselves with male prejudice as both indicator and cause of sexist bias. The demographics of enrollment at universities, participation rates in the workforce, and the selection of award recipients in a given field also are held up as proof of a wider climate of discrimination. A whole typology has emerged to categorize this evidence, a process that has made terms such as unconscious bias, stereotype threat and microaggressions common currency in media and academic discussions of the issue, even though such concepts rest on shaky scientific footings. In STEM, this body of evidence would serve to include anything from a “stereotypical ‘geeky’” work environment to a workplace with “an emphasis on logical thinking.”

My own experience has led me to question such arguments. That’s because all of these exact same indicators could be applied, in precisely the same manner, to make the case that men are the subject of systematic discrimination in the field of education. Yet I see no first-hand evidence of such discrimination. In fact, I see the opposite. My experience shows that sometimes gender discrepancies develop within a professional field for reasons that have little to do with discrimination, and everything to do with personal choice.

Because I am not inclined to think of myself as a victim—and have not been encouraged to do so by my educators—I do not systematically catalog instances in which I perceive myself to be discriminated against or subject to artificial barriers. While I am still completing my degree at a Canadian university, I already have served as an unqualified emergency supply teacher at the elementary level. During this time, a number of my experiences could certainly be taken as evidence of discrimination if I were eager to interpret the actions of those around me in the most negative possible manner. In one case, it was assumed that I was the parent of a young child, and not the teacher. On other occasions, it was presumed that I would prefer to teach older children, since that would follow the usual pattern among male teachers. In another instance, I sat around a table in the staff room as the lone male, and listened as female teachers discussed their experience at a male strip show in Las Vegas. Surely this could be categorized, by some, as a toxic and alienating work environment. I also was once warned by a fellow teacher that I should keep my distance from female students because one never knows when, and from whom, accusations may arise. If I were looking to cast myself as a victim, I would go to my bosses—or even the media—and claim discrimination, torquing these stories in such a way as to suggest that I had endured real emotional harm; that the field of education is truly hostile and exclusionary towards men. I would also name names and shame their alleged misandry.

But I don’t have a victim mentality, so I would never do such a thing. Moreover, I know that, even to such negligible extent that my experiences could be construed as expressions of sexist bias, they are orders of magnitude less significant than the very real (and often vicious) discrimination that generations of women faced when they began courageously taking their place in the workforce in the latter half of the twentieth century.

My parents were both teachers. Unlike my father and I, some men no doubt have abandoned thoughts of becoming a teacher because of the anticipated discrimination they might face, or because they felt the urge to pursue a more stereotypically male profession. But that’s their choice. And I won’t patronize them by calling them victims. Moreover, many of these men probably made the right choice, because, by my observation, there is something about teaching that really does appeal more to women than to men.

I have taught everything from kindergarten to grade eight, and am comfortable with students of all ages. Despite my lack of experience, I believe I am an effective teacher who creates a climate of comfort and safety for my students. But as a general rule, the younger the children, the less interest I have in teaching them. Not because my confidence has been sapped by prejudicial, misandrous colleagues scrutinizing my every move, but simply because, I, as an autonomous individual man, prefer teaching older children, full stop.

As noted above, my preference fits in with a commonly observed pattern. As pupils rise in age, so too do the number of men inclined to instruct them. This gender-based difference in professional focus should not surprise anyone, since men and women have different kinds of brains. On average, men are more interested in things and less interested in people. They underperform in verbal fluency compared to women; and score lower on the Big Five personality trait of agreeableness, and the Gregarious aspect of extraversion.

When teaching very young children how to read and write, teachers must rely on oral communication to maintain an enthusiastic, cooperative and amicable learning environment. Men, more than women, might balk at this kind of work. Also worth noting is the male tendency to score higher in the assertiveness aspect of extraversion, which might help explain a disproportionately high preference for instructing children who respond to sterner forms of direction without tears.

To say that women score higher than men in an area such as verbal fluency does not mean all women score higher in verbal fluency than all men. What this means is that within a large population sample, more women will tend to score higher on verbal fluency than men. Put another way: To the extent that measures of such traits may be represented by a normal distribution curve, the average (corresponding to the peak of the curve) will be shifted to the right for women vis-à-vis men.

Note also that most women and most men are not teachers; but those who become teachers tend to be those who score especially high on verbal fluency—a fact that exacerbates the female “advantage” (if one may use that term) thanks to the mechanics of Gaussian probabilistic distribution. Although you cannot determine on an individual level who would score better on a certain ability simply by looking at someone’s sex, you can, on a population level, determine what sex will be overrepresented in careers that tend to attract people with that ability. And despite what James Damore’s bosses at Google would have you believe, describing human abilities in this way isn’t tantamount to discrimination, because it isn’t inconsistent with the need to view people as individuals with unique talents and desires.

One strategy I take in my own professional life is to emphasize the positive. The majority of women I encounter in the hallways and classrooms of schools either go out of their way to encourage me to continue my career as an educator despite prevailing stereotypes, or are entirely indifferent to my gender and simply treat me in the normal respectful manner one expects from a colleague. Their stories about Las Vegas don’t affect me. Like everyone else, I could find evidence of bias and toxicity if I endlessly scrutinized their words and facial expressions. But I don’t.

I once had a college professor who spoke to our philosophy class for 20 minutes about how unwelcoming STEM disciplines are for women. (Don’t ask me how this monologue found its way into an introductory philosophy class, but it did.) When the class ended, I provided the professor with a recent study—from the same source as an older study he’d referenced in our class—that suggested prospects for women in STEM were much less gloomy than he’d indicated. As the semester went on, it bothered me that he never mentioned this new information to the class. Maybe he just forgot about our discussion. But I worried that female students in the class would imagine that they were destined to be victimized by sexists if they chose to enter technical fields. Had that same professor offered a similar soliloquy about education—or had I been continually reminded by the media about how education is a supposedly toxic environment for men, I might have become an accountant.

If the advocates who claim socialization is the root cause of gender underrepresentation in professional fields truly believe their own claims, it’s worth asking why they spend so much time trying to convince students that defying stereotypes will lead them into dens of bias and toxicity. Where true discrimination exists, we should fight it. But I have never heard of a travel web site that shows potential customers video footage of plane crashes.

If I were taking my cues from the activists who fight hardest for female inclusion in STEM, I might advocate for male quotas in education. But such a strategy would not only be insulting to men like myself, who feel they need no such leg up; but also discriminatory to the qualified women who would be passed over by such a system. Getting a job in this way would leave me mortified—and would naturally induce my colleagues to wonder, not without reason, whether I was truly qualified. Most importantly of all, it would mean that many children wouldn’t be getting the best available teacher. Instead, they’d be getting the best available male teacher.

Of course, there are those who might argue that quotas would actually improve education by supplying children with a more diverse pool of teachers. But that argument is problematic: If people with certain personality traits are, by nature, attracted to particular professions, what amount of intellectual diversity can be expected on the basis of gender? A man who is drawn to teaching may have just as much in common (or more) with a woman drawn to teaching than he has in common with male non-teachers.

That said, I can understand how gender diversity could have some benefits. For instance, perhaps having more men in education will result in more latitude when it comes to rough-and-tumble play, a crucial element in a child’s development. Instead of being suspended for throwing snowballs—even against the wall—students may not only be permitted, but encouraged, to engage in vigorous and spontaneous forms of physical behavior. But, as this very example may itself suggest, I suspect that the men who would bring the most viewpoint diversity to education would have the most trouble adhering to the increasingly regulated (some might say feminized) behavioral regimes prescribed by modern educators. The sort of men who now work in, say, the trucking industry, certainly are unlikely to find themselves well represented in early childhood education.

I have worked blue-collar jobs in factories, courier networks and construction sites. The men I’ve met in these industries, by-and-large, exhibit little resemblance in personality to those I have met in teaching. Much like myself, the male educators I have met, especially at the elementary level, are, as one might say, well in-touch with their softer side. That is not to say that we are weak, just that the skill set and personality characteristics required to instruct 12-year-olds on proper sentence structure in an air-conditioned building aren’t those needed to operate a masonry saw in blazing heat or bitter cold. If our goal is to get more men into teaching, we have to concede that we’re going to be getting only a narrow chunk of the male personality spectrum. So a quota on gender won’t provide as much viewpoint diversity as some might hope.

Moreover, such quotas would do nothing to fix the larger problem in education, which (as in many other industries) is an overarching antipathy to new, unorthodox theories and techniques. Like everyone else, we need to fight the tendency to self-organize into echo chambers and positive feedback loops that insulate faddish ideas from criticism (one of those faddish ideas being the current fixation on gender diversity for its own sake).

This essay is primarily about men in the field of education. But I hope that even a casual reader will note that every argument I have made could be flipped on its head, with genders reversed, and applied with equal force to STEM. At the end of the day, women and men are different, and they will make different choices in deciding what to do with their lives. Indeed, longitudinal studies from Europe indicate that the more gender equity that exists in a society, the more men and women tend to embrace certain stereotypical career tracks.

To the extent that men and women can provide divergent yet complementary perspectives, it is beneficial that we have at least some gender diversity in all fields. We are long past the age when we would tolerate an all-male supreme court, for instance, or an all-male university faculty. But personal choice always must be paramount. This isn’t just an abstract statement of my moral belief. It is a conclusion rooted in my empirical experience in a female-dominated field.

From a young age, boys and girls need to be encouraged to follow their passions. If a boy is attracted to teaching, he should be encouraged to pursue this career. But if later, that same boy decides he would rather work in construction, we need not second-guess him by insisting that his viewpoint is socially constructed or the product of discrimination. A world in which more men operate cranes and more women teach children does not present a problem. The real problem is the ideology that demands we treat it as a problem.